We were lucky to catch up with Lucie Van der Elst recently and have shared our conversation below.

Lucie , thanks for joining us, excited to have you contributing your stories and insights. Can you talk to us about how you learned to do what you do?

Drawing is a universal language that I had the chance to learn at a very young age. My dad, an incredibly skilled drawer, took it upon himself to teach me the art of pictograms. By simplifying an object, action or animal, it is possible to make it legible by everyone. My dad and I would draw stories together, and played a game called tac-o-tac : a kind of freeform exquisite corpse. He would draw a character, I would draw a road, he would add a futuristic car, I would counterattack with a dragon. We would also look at so many books: political drawings, Flemish portraits from the 1500s, the works of Roland Topor, Saul Steinberg, Etienne Delessert, Rita Mercedes, nature illustration and anatomical books, and hundreds, thousands more. I would look at each image for a really long time, wondering how the artist did it, what detail they’d spend time on, what challenges they confronted.

Later, I was one of the lucky few who could apply to a high school with an extra focus on art. It was a public school, all you needed were good grades and an interest in visual arts, of course. Through the teachings of illustrator Nancy Pena, I could learn a little more about the “how” and “why” of visual representation. We practiced watercolors, gouaches, acrylics, pastels, ballpoint pen, and india ink with a bamboo pen we fashioned ourselves. Why would you choose one particular medium or technique over another? How can an artist skillfully deploy these elements, for a calculated emotional effect?

On the other hand, a high school teacher (going by the pseudonym “Shoboshobo”) showed me that it was absolutely OK to let the gesture and the medium be free – to draw whatever I wanted, however I wanted. Technical perfection wasn’t necessary if it had character and got to the point. I remember him taking the class to a David Shrigley retrospective – how incredibly funny and smart those drawings were!

I am so glad I got to see both ends of this creative spectrum.

Now, back to the question, I don’t think speeding up the learning process is desirable as an artist. In this age of instant gratification, artists are under pressure to adapt to new trends and to produce content constantly to stay visible. There might be techniques to learn that speed up some steps – Photoshop shortcuts or fast-drying paint – but the creative process itself can’t really be rushed. It requires slowing down the world around you and focusing on one thing for a while. It demands time for daydreaming, for mindfulness. It asks you to put your phone away, to observe, feel, and reflect. To look at a tree during a walk, to see how it connects to the ground and how the ground connects to your feet. You can even draw it all in your mind, with one unbroken line.

As useful as they are (I couldn’t live without my phone), having our thoughts constantly interrupted by notifications or the desire to get notified is getting in the way of a state of creative flow.

Lucie , before we move on to more of these sorts of questions, can you take some time to bring our readers up to speed on you and what you do?

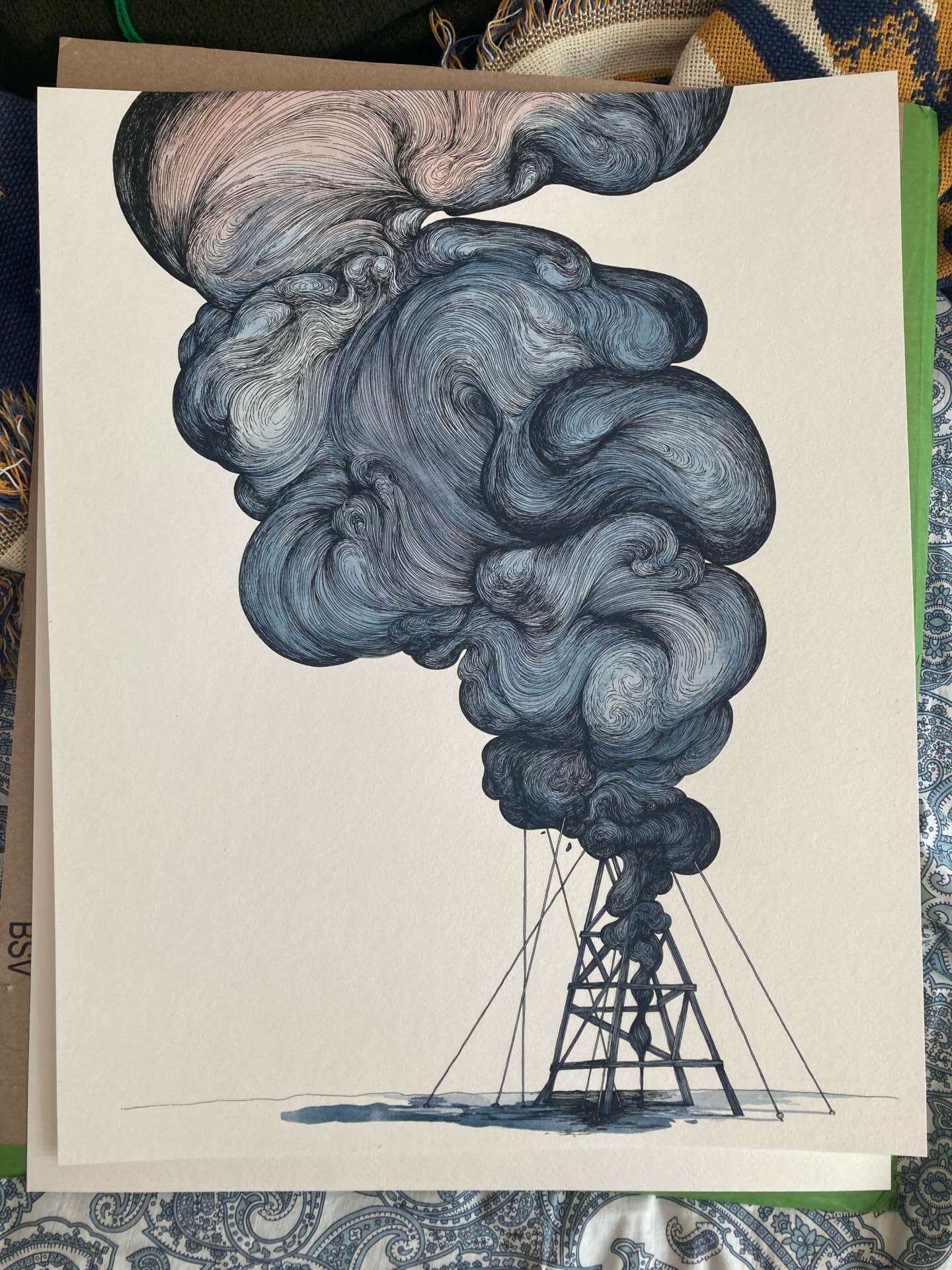

In the years since I graduated I explored many disciplines but in my personal work I mainly draw with ink and watercolors. My main focus is making emotions tangible. In my case, words are not enough. I’m not a great musician or dancer either, so drawing is the most direct way for me to approach complex and sometimes paradoxical themes, like grief, family ties, doubt, and wonder. I keep returning to the same physical subjects: birds, minerals, and plants. Through the process of drawing, they transform into something other than themselves, something less distinct. People can tell I’ve drawn an egg or a bridge or a stone. But something else is in the picture, and the game is to find out what it is. I’m often pleasantly surprised by what people discover. Some viewers find their own route, their own stories to tell in my imagery. It becomes theirs. This is the most precious aspect of my artwork, the reason I keep doing what I do.

Learning and unlearning are both critical parts of growth – can you share a story of a time when you had to unlearn a lesson?

I’m trying to make peace with uncertainty. It took me about twelve years to understand that things might not make sense right away after college, career-wise or even artistically. Projects might be left unfinished before they’re resolved, sometimes for years. Life is everything but a straight line. You may find yourself on the path to exponential growth and profit (and I’m wishing this for us all), but you can also get stuck in a rut for a long time.

Over time, you start to notice patterns. For example, I realized that after each big project or deadline, I experienced doubt and felt deflated. I learned to give myself grace and take this as a sign : it’s time to recharge, read a book, go to an art exhibition alone or with a friend, to do some random non-artistic activity – something that’s not productive or profit-driven.

Are there any books, videos, essays or other resources that have significantly impacted your management and entrepreneurial thinking and philosophy?

I will recommend two books that helped me define my core values. As weird as it sounds, as far as interpersonal relationship advice goes, I always advise reading The Moomins. I grew up watching the Japanese adaptation of this Finnish classic by Tove Jansson, and not only is it absolutely delightful, it is full of little fables about personal freedom and acceptance. All the characters have different lifestyles, yet they coexist and have tea together. Some of them are settled, some of them come and go with the seasons. Some of them are gregarious. Others prefer to be left alone. The scary characters are mostly misunderstood. It is far away from the manichean worldview that is often imposed on us at a young age, especially in the United States. A second book I would recommend is The Man Who Mistook his Wife for a Hat, a 1985 collection of essays by neurologist Dr Oliver Sacks. It’s a compilation of extremely rare cases where science meets the fantastical. The patients, while seeming “normal” from outside, are experiencing entirely different realities, dictated by the connections (and disconnections!) in their brains, nerves, and muscles. What makes this book so powerful is Dr. Sacks’ compassion when describing people’s conditions and how they must navigate in the world. There is no sensationalism whatsoever. And while each story is incredibly moving, there is a sense of poetry and wonder in Sack’s reflections about the mysteries of the human brain.

I have relationships with quite a few neurodivergent people (with differences ranging from the obvious to the barely detectable), and I often return to this book for how it illustrates how an experience of the world may be totally different from one person to the next.

Keeping this in mind while interacting with one another would most certainly help strengthen our empathy muscles. I try my best to let this awareness guide me through the world, rather than projecting my own framework onto everything.

Contact Info:

- Website: https://www.lucie-vanderelst.com/

- Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/lucie.van.der.elst/

Image Credits

@nickmerlockjackson