Alright – so today we’ve got the honor of introducing you to Lisa Pahl. We think you’ll enjoy our conversation, we’ve shared it below.

Alright, Lisa thanks for taking the time to share your stories and insights with us today. What did your parents do right and how has that impacted you in your life and career?

Everything happens for a reason.

I despise this phrase.

I don’t believe that when a child dies or thousands of people are killed by a tsunami that there’s some magical reason for it.

I do believe that significant growth can come out of difficult situations.

I was eighteen years old and a freshman in college when my father was diagnosed with Hairy Cell Leukemia, a rare cancer of the blood. My father developed symptoms of fatigue and low-level depression. The diagnosis wasn’t made until his platelets were so low that he required immediate hospitalization.

Needless to say, our family was taken aback by this diagnosis and my father’s hospitalization.

To provide some context, my parents were married at eighteen years old. They had my brother and I while still in their early twenties. My dad was a truck driver who worked sixty hours a week. That was before the twenty hours that he put in on our family farm.

As a child, I knew that my dad loved me, however, I also felt that his priority was working. A great deal of our family time was spent grinding feed, cleaning animal pens, picking corn, cutting firewood; farm stuff.

When my dad was diagnosed with cancer, I didn’t know how to respond. I remember I had a cold, which I used to keep my distance during his hospitalization. Eventually when I visited him, I brought along a mini- basketball hoop that hung on the door so we could shoot some hoops together. The look on his face when he saw me walk in the room has remained with me to this day. He was so thankful that I came. I could see in that moment how much he loved me.

Upon leaving the hospital, I saw a different man emerge. This man cried. He wrote in a journal every day. He became sentimental. He asked questions about my life. He continued to work sixty hours a week, but retired early. The farm animals were sold.

When my son was born fifteen ago, my dad wept openly. He then proceeded to call me every night for three years to say, “Give the big guy a hug and kiss for Gramps.”

Gramps is patient, playful, kind, and very affectionate. There’s no question my son knows just how much Gramps loves him.

My dad has had multiple rounds of treatment over the last twenty-four years. At this time, though he requires frequent bloodwork and monitoring, he is healthy. He runs three days a week and stays busy on their forty-acre property. But it’s likely he will require treatment again.

Because his cancer is slow growing, typically treatable, and has not impacted his day to day physical health, our family has considered his cancer diagnosis a bit of a blessing. While we will never know his path had he not received this diagnosis, I firmly believe that the father, grandfather, spouse that my dad is today is because he was confronted with his mortality.

This concept of mortality awareness, and the richness it can bring to life, is a big part of what led me into a career working in death and dying.

Lisa, before we move on to more of these sorts of questions, can you take some time to bring our readers up to speed on you and what you do?

I began a career in end-of-life eighteen years ago as a hospice social worker. After some time working in hospice, I added seven years in emergency medicine to my resume, assisting those with psychiatric and medical emergencies. In both of these settings, I was struck by how fearful people were to talk about death, how very unprepared most were. Even on hospice, when you must have a terminal illness diagnosis and a prognosis of six months or less, people are still reluctant to talk about death and dying.

When people avoid thinking or talking about death, they typically avoid making any preparations for their end-of-life or after death. This results in the family experiencing conflict or indecisiveness regarding medical decisions, the person likely not having the life or death that aligns with their wishes and values, and extra work and stress after death when the grievers must try to settle their affairs.

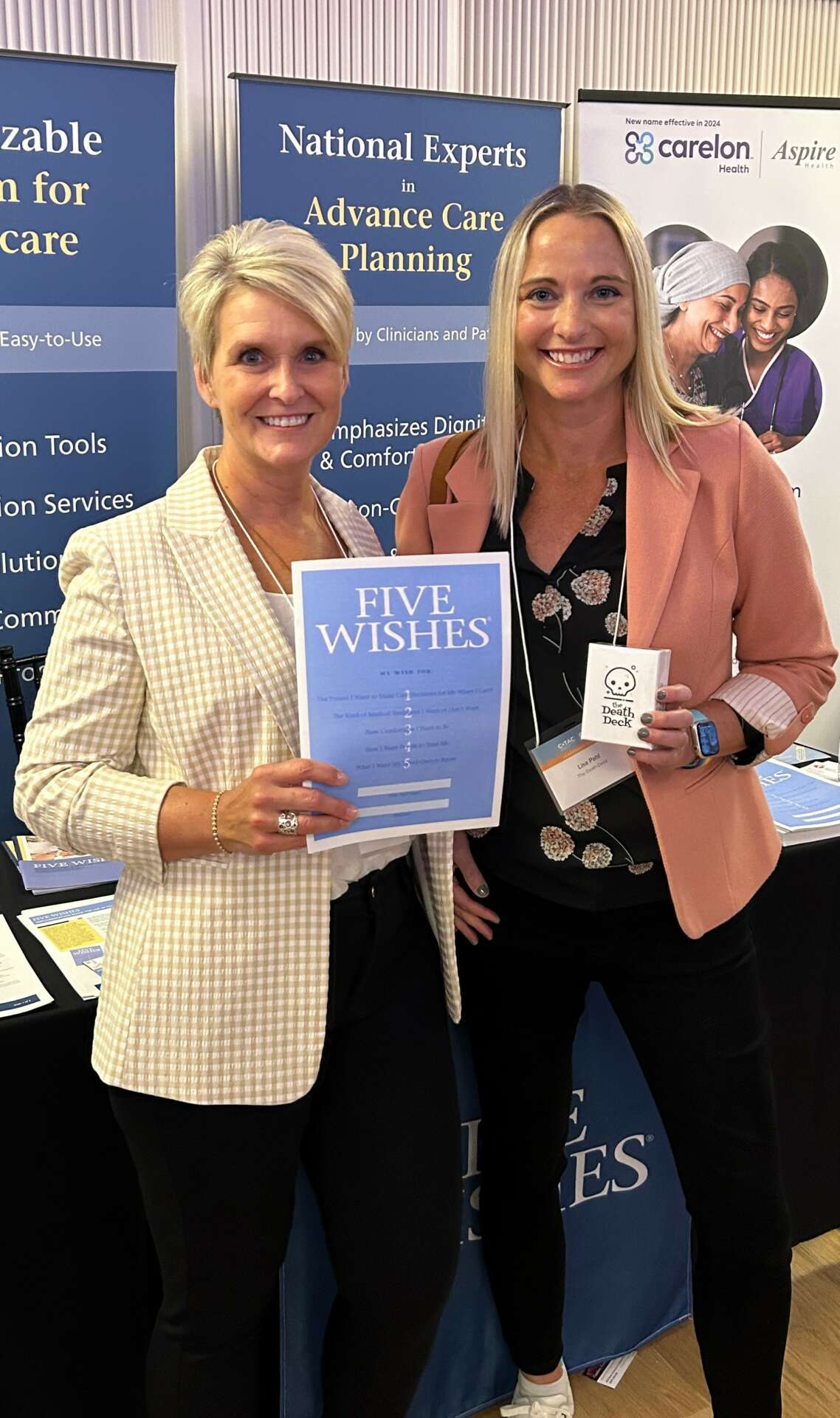

With this knowledge and a deep desire to help people become better prepared for their death, In 2018, Lori LoCicero, the spouse of a former hospice patient, and I launched our company, The Death Deck, based on our card game of the same name. The Death Deck is a game and tool that allows friends and family members to open up and share thoughts, stories, and preferences about life and death in a non-threatening and surprisingly fun way. Players partner up to guess answers to deep, funny, and important questions on death.

People play The Death Deck as a party game, a conversation tool, a way to start advance care planning conversations, and as prompts for tasks like estate planning. There are questions about general thoughts related to death (can mediums communicate with the dead?), personal beliefs and desires related to dying (would you consider sending your cremated remains to space?), and death preparation and advance care planning (should price factor in when making healthcare decisions)?

After a few years, we knew that people were finding The Death Deck to be useful, and also we knew that our light-hearted and humorous Death Deck wasn’t the best tool for those who are nearing the end of their lives.

In 2023, we launched our second tool, The End-of-Life (E•O•L) Deck. The E•O•L Deck is designed for people in their final chapter of life, including those with life-limiting diagnosis, hospice/palliative care patients, and people of advanced age. It’s more sensitive, using softer language and images while also utilizing the casual tone and multiple-choice questions like our original product, The Death Deck.

The E•O•L questions are more specifically related to end-of-life preferences (rather than a wide range of death-related topics) and legacy building. Questions like how do you feel about touch? Visitors? Chaplain support? The use of sedating medications? The E•O•L Deck is being used by healthcare professionals and caregivers to help patients define what they want during their final days. For states in which Medical Aid in Dying is legal, The E•O•L Deck is an especially effective tool for orchestrating those final precious moments.

In addition to creating tools to help talk about death, a large part of what we do at The Death Deck is to normalize death and dying conversations in the community. We’ve partnered up with other end-of-life professionals to create events that focus on bringing death and dying conversations out into the open.

We co-host a monthly Silent Book Club of Death in a local brewery where participants bring a book of their choosing (or choose from our library) on the subject of death, dying or grief. We read silently, then mingle and share. We’ve met so many curious community members who are increasing their death literacy each month.

Another ongoing program that we are involved in is Death Over Drafts, now occurring in eleven states and Canada. Death Over Drafts is a community event often hosted by a death doula or other end-of-life worker to spark curiosity and connection around death and dying. Typically taking place in the casual atmosphere of a brewery, participants use The Death Deck and The E•O•L Deck to explore their thoughts on death and dying topics.

We also participate in community education activities at senior centers, libraries and health fairs, providing information on topics related to end-of-life and highlighting the importance of being prepared.

Creating our decks and educating others on end-of-life brings me such personal joy and fulfillment as I know that people have more peaceful deaths when there have been conversations and preparation over time.

Other than training/knowledge, what do you think is most helpful for succeeding in your field?

Working in end-of-life means that you have not only have to develop significant self-care routines, but also maintain appropriate boundaries.

When I first became a hospice social worker, I struggled with maintaining appropriate boundaries for my well being. While hospice is available 24/7, as an employee, I had scheduled shifts. I would find myself worrying about my patients and families a great deal during my free time. I would have images of dying patients flashing in my mind in the middle of the night. It felt impossible to compartmentalize this type of work. These people were dying, and their dying didn’t stop when my shift ended. As much as I felt called to this work, it all felt overwhelming.

What I learned over time and with great mentors, is that I would not be able to continue doing this work that I was so passionate about if I couldn’t establish some stronger boundaries.

I began letting my patients and families know that I would not be able to answer phone calls and texts when I wasn’t working. I built up my communication skills (written and verbal) so that I could have confidence that my team members could fill in when I wasn’t working. I put effort into developing stronger relationships with my team members so that we could trust each other to provide quality care in our absence. I began journaling about difficult cases and situations so that I would stop ruminating about them after hours.

Once I developed stronger boundaries, I was better able to be present and enjoy my life more; which brought joy and balance to my work.

How’d you meet your business partner?

A few years into my career as a hospice social worker, I arrived to the home of my new patient, Joe. Joe was in his early 40’s with two small children. He had been diagnosed with pancreatic cancer a year prior and had made the declaration that he would beat it. Unfortunately, this meant that there were very few conversations about what might happen should he not survive this horrific diagnosis.

Joe was on hospice with us for two weeks and two days. From the day he was admitted, he was transitioning, a phrase that refers to the process that a body goes through in the final one to two weeks of life. He was still awake, however, he was altered and confused. He was no longer able to speak for himself. His wife, Lori, had many questions about what would be best for Joe during this time. She wasn’t sure if he would prefer to be more sedated or more aware; if he would want his siblings and other family members in the home, or just his wife and children; if he would want music playing or prefer silence. So many questions.

Lori did a beautiful job with the information she had, providing for Joe what she inferred he would want. After his death, I provided bereavement support for Lori. We talked at length about the many questions that remained in her grief. Did she honor what he would have wanted?

I provided grief support for Lori for a couple of years, stretching the boundaries of how long is typical for hospice support. A few years later, I received a call from Lori asking to meet up for coffee. We developed a friendship and began talking about the fact that people are so afraid to talk about death. With Lori’s personal experience and my professional experience, we decided to create a game that could help people begin these oh-so-important conversations.

We launched The Death Deck in 2018 with a mission to normalize conversations on death and dying and help people prepare for this final stage of life.

Contact Info:

- Website: thedeathdeck.com

- Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/thedeathdeck/

- Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/thedeathdeck

- Linkedin: https://www.linkedin.com/in/lisa-pahl-lcsw-89669070/