Alright – so today we’ve got the honor of introducing you to Lindsay Jordan. We think you’ll enjoy our conversation, we’ve shared it below.

Alright, Lindsay thanks for taking the time to share your stories and insights with us today. One of the things we most admire about small businesses is their ability to diverge from the corporate/industry standard. Is there something that you or your brand do that differs from the industry standard? We’d love to hear about it as well as any stories you might have that illustrate how or why this difference matters.

“It’s not charity. It’s kinship.”

I recently heard a conference speaker offer this explanation of a framework my company uses with our clients, and I just fell in love with it. In the nonprofit world, the concept of donor-centric fundraising is an accepted best practice, and it basically means that the donor is always right, always respected, always recognized, always deferred to. And it’s total bullshit.

I started Write On Fundraising in 2018 after having spent the previous 10 years – my entire professional career – in nonprofit fundraising. I both loved and loathed my work – raising $32 million for worthy nonprofit causes, building relationships with the families we served, being able to share with my children the pride of caring for others… that was fulfilling in a way I can’t even describe. It was work that fed your soul.

But watching talented fundraisers crash after less than a year in their job or spin out of the sector entirely, observing unhinged boards as they degraded and dismissed exceptional leaders in the community, being groped and addressed inappropriately by some donors, being asked to fudge reports for private foundations by poor management, and trying to keep my head above water in a field that excuses so much inexcusable behavior, that wasn’t worth it. And I believed with every fiber of my being that fundraising could be done differently. Better. Equitably.

That was the start of philanthropic equity for me, and the foundation of my company. Philanthropic equity addresses the power imbalances created by traditional donor/fundraiser and donor/organization fundraising practices that negatively impact philanthropy; create a standard of conduct that centers respect and collaboration; and dismantle structural inefficiencies that contribute to turnover, burnout, and loss of talent in the field of fundraising.

Yeah, we raise money for nonprofits. A LOT of money. In the past seven years, we’ve raised nearly $250M and served more than 300 organizations. My team of about 15 full-time staff are experts in their field, but it’s our framework that sets us apart from our competition. It’s our commitment not to just fundraising, but to changing how fundraising happens that has made us truly successful.

Our framework is:

– Codified in our mission and vision statement and in our values

– A guide for which clients we want to work with, and which we don’t

– A policy for pay equity, remote work, and the majority of internal policies that make up our culture

– Discussed, unpacked, and analyzed every month through internal staff programming

– A prerequisite for employment

– Exemplified for our clients in the language and images we use, the processes we have created, and in the best practices we use internally

– A system of healthy boundaries that protect our staff and set the example for clients

– Frequently requested by our clients in the form of our policies that they can share with their boards

– The beating heart of the company

Great, appreciate you sharing that with us. Before we ask you to share more of your insights, can you take a moment to introduce yourself and how you got to where you are today to our readers.

I always wanted to be a writer. I wrote my first book in 2nd grade. It was called “The Whole Note” and I couldn’t really spell many words so it was mostly a picture book about a sad little half-note who wanted to be whole (I was also part of a very musical family). The love of writing stuck with me and was nurtured by my family, particularly my mother, a court reporter, who was a stickler for proper grammar, spelling, and expanding one’s lexicon to the max.

But “writing” is a big field of opportunity. Mathematicians write. Politicians write. Movie directors write. What did I want to write? Before I had the opportunity to give it much thought, I was 18, graduating high school, in love, and moving across the country to start my own life. Kind of.

Within a year of a youthful marriage, it was clear to both of us that we were playing house and failed to recognize or appreciate the depth and maturity required for a forever-coupling. At 19, I proposed we cut our losses and head our separate ways. He agreed.

In the state of Tennessee, you have to wait one month from the date you file for a divorce to the day it can be granted by the judge. My guess was this is for people who work it out and decide to give it another go. In our 30-day waiting period, Jason, my requited husband, had a check-up at St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital, which is where we originally met. My little brother, John, had childhood cancer, and my family would travel up and down I-40 from Poteau, Oklahoma to Memphis, Tennessee for his treatments. It was during one of these visits in a hospital room where I met Jason, who had been diagnosed as a teenager and who also traveled back and forth with his family. And it was in a hospital room where Jason received news that would change both of our lives: he had relapsed.

Now, I had a decision to make. Jason told me I could go. We had already agreed on it. In my mind, I could envision two paths. One would take me right back to college, where I felt like I had detoured from and was expected to be. The other would take me to a hospital, where I didn’t know what would happen. I had a sense that my decision would define what kind of person I was, or would be, and I decided flatly that I did not want to be the type of person who would leave. So I stayed.

Jason and I lived in Memphis for the next three years where we underwent chemotherapies, radiation therapies, and stem cell therapies, and where we fought off fungal infections, complications, pain killer addiction, malnutrition, and deep isolation. We were no longer partners in a marital sense; I was his caregiver, and he was everyone’s very reluctant patient.

In case you aren’t familiar, most cancer advertisements lie. Cancer is portrayed as this thing that is sad but, with a choir of champions at your back, you will overcome. The images are full of cheering, happy people beating cancer, ringing bells, and living life. The reality of cancer treatment is not that.

There were days when Jason begged to die. There were doctors who wouldn’t let him. There were families who fought about finances in the hallways as their child sat with an IV in their arm. There were moms and dads who ate only because the hospital partnered with a grocery store nearby that provided gift cards. There were many marriages that ended because the burden of the medical crisis was simply too heavy to bear. There were children who died alone.

One of those was Josh. We met him and his older brother, Brandon, at a Thanksgiving dinner provided for patients still receiving treatments, or too sick to go home, for the holidays. We also met their mother. She was grief-stricken when we met her. She had been adopted as a child, and didn’t know that she had a gene that carried with it a lethal blood disease, but only for boys. Josh and Brandon were fighting, but they were losing. And she was falling apart.

One evening, Jason and I were asleep in the hospital. He had been on the fourth floor – the floor for terminal patients and experimental treatments – for about a month. He spent most of his days asleep. When awake, he was in unconscionable pain. So sleep was better. Much better. At the blaring sound of the alarm, I shot off the little couch and raced across the room. Jason was still asleep, and the incessant beeping wasn’t coming from his room. It was coming from across the hall.

I walked to the glass wall facing the hallway and other rooms to see Josh, his little 8-year old body tangled up in white blankets and not moving, all the flashing lights and alarms alerting the staff that something was very wrong. Doctors and nurses began pouring into his room. I stood frozen at the window and watched as they worked to save him, to bring him back. After what seemed like not nearly long enough, they stopped. They gently covered his body and left his room, and I stood in the dark and quiet, crying.

Josh died alone, fighting for his life.

And in that moment, I had an out-of-body experience. I felt the weight of the universe press upon me. The world was not fair. The world was not just. The world just, was. Concepts like what is fair and just require people to breathe meaning into them. Children like Josh – those who fight to live – deserve to live. The scale just needed to tip in their favor. And therein, I found my purpose: to be a counterweight. It didn’t have to be a lot. I didn’t have to swing for the fences. But if I could add my weight – my skills, my voice, my work – and help tip the scale toward something good for someone else, someone like Josh, then it would be worth it. To live with dignity. To die on your own terms. If nothing else, that must be the basis of all humanity.

And that’s how I became a fundraiser. Well, kind of. Jason walked out of St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital cancer-free and, as originally planned, we parted ways. I went to school and pursued, you guessed it, writing – or journalism specifically. I spent those years, hungry to make up for lost time, gulping down internships and low-pay/no-pay career opportunities. At a public relations firm, I found fundraising… or, rather, fundraising found me. And everything clicked into place.

Fundraising is where my skills as an exceptional communicator met a paycheck that I could build a life around met my purpose of tipping someone’s scales for good. The Japanese refer to this as ikigai, the intersection of what you love, what the world needs, what you are good at, and what you can be paid for. I found it when I was 26. It is not something I take for granted.

I have had a tremendous and humbling amount of success in my life. I parlayed a successful career into a successful business, and somewhere along the way was fortunate enough to be blessed with an incredible husband and two boys of my own.

And although fundraising is the ground where I’ve planted my flag, I don’t attribute the achievements in my life to being the best fundraiser in the room. Remember, mathematicians write… so do politicians and movie directors. There are countless places my talents could have taken me. I believe my life is bursting at the seams with blessings because I know and live my purpose, and because I made the decision a long time ago to be the kind of person who stays. I’m still here.

Are there any books, videos or other content that you feel have meaningfully impacted your thinking?

There are (currently) two books that serve as the basis for our company: Radical Candor and Daring to Lead. Radical Candor is particularly important because it provides a management framework for clearly and candidly providing feedback to team members WHILE maintaining (or even strengthening) your relationships. I thrive on candid feedback, and I give it constantly. It’s important for staff to understand how and where they can (and should) push you. No one is a fully formed leader – we’re all growing all the time. And I believe that growth should be leaning into the people you lead. At Write On, the full staff gives me a 360-degree review every fall and the management team gets their own 360-degree review in the spring. Every employee takes part in a quarterly workplan with standardized performance metrics, milestones for advancement, and custom metrics. Once a year, that quarterly workplan serves as their annual review. After being told too frequently in my own review that I needed to “smile more,” it is very important to me that my team members receive actionable, valuable, and objective feedback on a regular basis. Radical Candor provides a great framework for that.

Daring to Lead is less about HOW to provide the feedback and more about how to practice vulnerability as a leader. We all want to bring our most authentic selves to work, but that requires that leadership is intentional about cultivating a space where people feel safe to be their authentic selves. (And if someone is authentically an asshole, how do you handle that?) Daring to Lead is a great tool for leaders to look inward and do some foundational work that will impact the way all employees show up.

We often hear about learning lessons – but just as important is unlearning lessons. Have you ever had to unlearn a lesson?

I spend a tremendous amount of time teaching my employees how to let go of toxic nonprofit culture, and I had to teach myself first. The best way to do it, I found, was to codify it. The reason we have 27 paid holidays a year (which is a lot) is because nonprofit professionals are conditioned NOT to take time off. Maybe there’s no backup for their role. Maybe they are worried about what will happen to clients if they step away. Maybe there is trauma bonding among staff and they don’t want to leave each other. None of that is healthy. And I can tell people to take PTO all day long: it won’t make a difference. Building POLICY around healthy boundaries, however, literally forces a change of perspective. I’ve had to go to the mat for my massive calendar of paid holidays in the past, but it’s proven to be an extremely effective way of forcing a paradigm shift. Breaking conditioning is hard.

Contact Info:

- Website: https://www.writeonfundraising.com

- Instagram: @writeonfundraising

- Facebook: /writeonfundraising

- Linkedin: /writeonfundraising

- Twitter: @writeonfundrs

- Youtube: /writeonfundraising

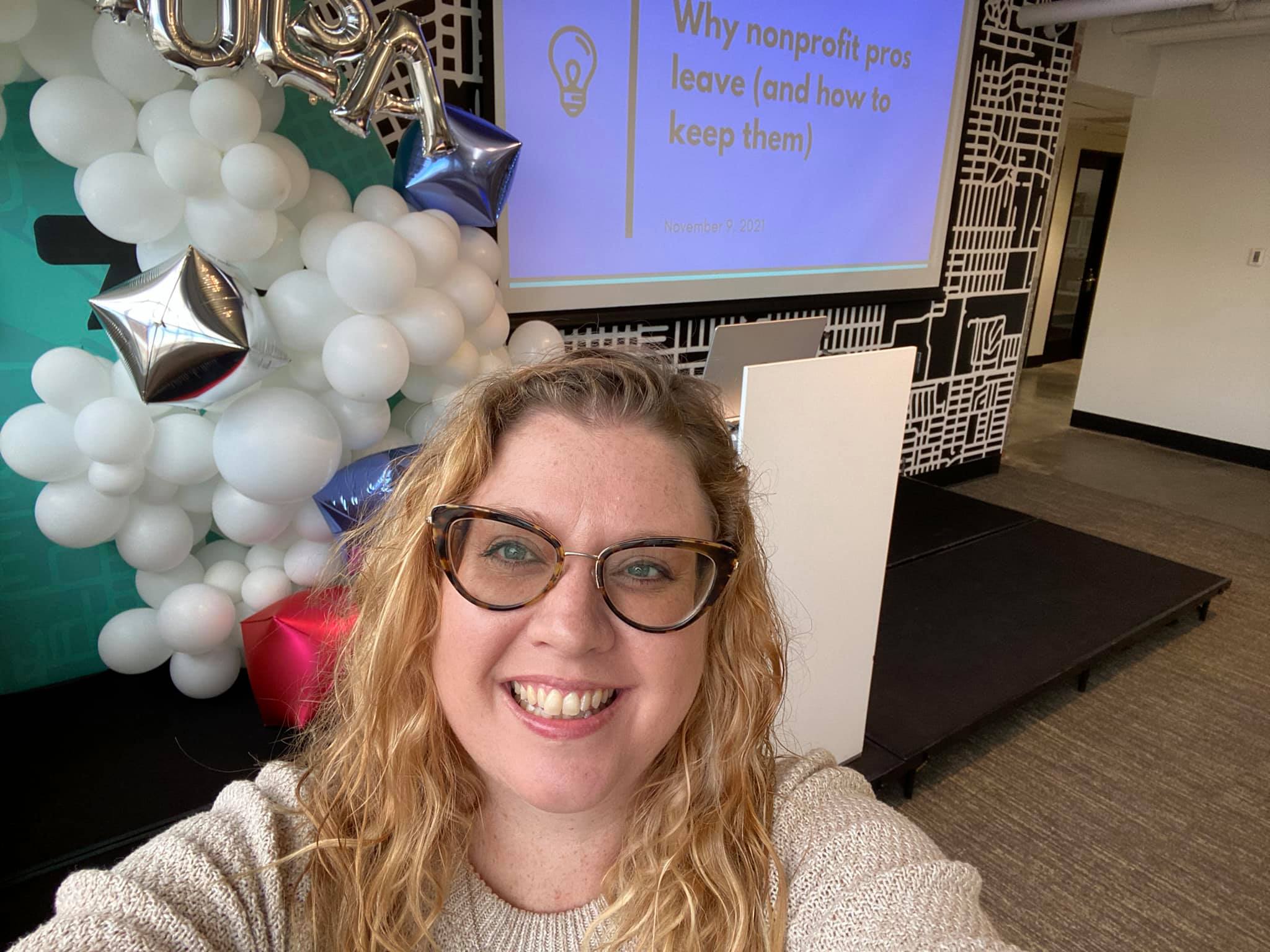

Image Credits

I took all these photos