We’re excited to introduce you to the always interesting and insightful Linda Kaye-Moses. We hope you’ll enjoy our conversation with Linda below.

Linda, looking forward to hearing all of your stories today. We’d love to hear the backstory behind a risk you’ve taken – whether big or small, walk us through what it was like and how it ultimately turned out.

There are many tales of risks I’ve taken in my life as a studio jeweler, not the least of which was, when, as a single parent, I was invited by a friend, a goldsmith, to take a class with her, learning to make jewelry. Backing up a bit, I need to mention that I had always loved jewelry, from the time I was permitted to invade my aunt’s jewelry box, the kind that opened on scissored levels to reveal trays upon trays of glittering costume jewelry. My friend’s invitation was, “Linda, I have heard you perform (from the late 1950’s through the 1970’s I was, yes, a folksinger) and now you must come see what I can do.” I had already been making strands of ethnic beads and selling them at folk festivals, and she saw a glimmer of what I needed to learn.

I had no discretionary money, but at the time, I was working as a counselor for ex-offenders at the local community college where she would be teaching her introductory jewelry making class, and so could take the class for free. I knew that this would be risky, mostly because I understood that my attraction to making jewelry might develop into an overwhelming exercise in self-indulgence (I was prophetic). However, I took the offer from my friend and jumped in.

A brief prelude is appropriate here. I had, from early childhood, considered myself to be an artist, and was encouraged by my mother to consider myself to be that. As I grew up-ish (still in process), I found that I was not a painter, a sculptor, in fact, I was not what was, in those unenlightened times, anything like an artist. I became a folksinger and a fiber artist and thought that would be it. Not!

The minute I touched a saw to metal in my friend’s class, I knew I had found my medium. Risk be damned, I was ‘home’, blissfully sawing pendant designs, making rings, setting stones, all with the least amount of tools imaginable. Will Rogers said, “Climb out on a limb. . . that’s where the fruit is!” and I climbed, no, I leapt.

Several years later, still making jewels, I had remarried, and my husband and I had bought a house. I was on unemployment, without having been able to land a job (unemployment rate was at 7.5%), but my husband had a full-time job. But then. . . suddenly, his job was eliminated and, although he had part-time work, we needed income (remember those kids, now a few years older, plus a mortgage). Time to climb out on that limb again. My husband and I discussed bringing my jewelry making to a more professional level and decided to begin to apply, full time, to juried craft shows. Deep breath here, because it’s a lousy way to find work. . . your livelihood depending on a panel of jurors allowing you to be in a place where you can meet potential customers and all of it depending on images submitted to the jury members. Big Risk! I did retail shows and developed product lines for wholesale (at one point I was making jewels for over 150 galleries and shops). At the same time, I had begun to teach and was running a Jewelry/Metals studio for a local art center. Talk about risk. . . I was risking any chance of down time. Fast forward almost to the early 2000’s and I was able to drop the wholesale business, only making and selling my one-off jewels directly to my collectors at shows, only making the jewels my heart told me to make. I’m still at it, though I’m beginning to taper off the quantity of jewels I make and the number of shows I do.

As always, we appreciate you sharing your insights and we’ve got a few more questions for you, but before we get to all of that can you take a minute to introduce yourself and give our readers some of your back background and context?

I’ve always wanted to make ‘stuff’ and was lucky that I was encouraged in that lovely obsession by my mother. In fact I was irrepressible. I drew all the time, made small constructions with whatever was at hand, and wanted to live in the craft cabin at summer camps. It did take me quite awhile, many years in fact, to find out that my medium was metals with the added delight in using gemstones and occasional found objects.

I was actually trained as a speech therapist, but rapidly discovered that was not what I was supposed to be doing on this wide planet. I had my two children with my first husband, got divorced, and was thirty-five before I held a jeweler’s saw in my trembling hand (trembling because, the risk, that climbing out on a limb thing, and also because I was so excited by the prospect of learning to make jewelry, that my adrenaline level was way above normal).

Once I began to make my jewels after that class, I realized that I needed to embrace a few more techniques (if you’ve ever made jewelry, you know that’s a huge understatement. . . I needed to learn a boatload). I talked with exhibitors at shows, asked questions of them about how they did what they did, took a few workshop classes when I could, and borrowed or bought every book I could find on making jewelry (and read them cover to cover).

I joined a national organization of jewelry makers and applied for/won State arts grants that helped pay my way to their conferences. I stuffed myself full of information, bought more tools, networked with like-minded makers, paid my dues at terrible craft shows, and I came out the other end knowing how to make a living doing something I loved doing. I have to add here that my second husband, who has photographed all of my jewels, began to handle some of the business aspects and, of course, the all-important job of setting up and tearing down at craft shows.

I reached a point where all I wanted to do was make my one-off jewels. That’s what excited me the most, and still does to this day. I also wanted to be able to ‘pay it forward’ and so I began to teach some of the techniques I had learned. I taught classes in the States, and three workshops in New Zealand. I founded and ran a jewelry-making studio at a local art center, brought in instructors from all over, and ran that program for eight years. All of that while doing shows! It was exhilarating and exhausting. Eventually, I scaled back to just doing shows and doing commissioned work for my collectors.

I am most contented sitting at my bench making my pieces and have found a community of collectors who continue to acquire, own, and wear my art, helping to support me in my pursuit of making pieces which fill my creative bones with joy.

What do you find most rewarding about being a creative?

It’s clear to me that every human being is born wanting to make stuff. Talent is a myth. Artistic talent is simply a combination of opportunity, the creative drive that everyone has, and applying the ‘seat of one’s pants to the seat of a chair’ at a bench or wherever any artist needs to be to do her/his work. Talent is also doing the above repeatedly, day after day, for all one’s life, until the work that one is compelled to do has been done. In my case, it is recognizing that what may appear to be an obsession is, in fact, a life-affirming process that my innermost self requires as sustenance.

In your view, what can society to do to best support artists, creatives and a thriving creative ecosystem?

In the creative segments of our society in the States, the loudest voices get the money, and that generally means that museums, performance venues, art centers, and other cultural organizations tend to receive the most attention when it comes to grants and other funding processes. This, of course, is based on the premise that these organizations benefit the largest populations and, therefore, benefit society at large more than individual artists might. This is a false premise.

So what is it that artists want and need? We need an environment that values our work, which means that arts education, at all levels, must expand in order to create an appreciation of the value of the arts. Currently, arts programs are contracting and funding is being reduced and redirected to STEM programs. That’s not to say that STEM programs are not valid, it’s just that when they are introduced into educational systems, funding for the arts is generally decreased.

Individual artists, emerging and experienced, need an audience that is educated to expect the need for artists to be compensated financially appropriately, potentially by grants-funding, at the same level as major cultural organizations, but also via venues where artists present their work for sale. This latter is dependent on an informed audience, an audience where sticker-shock is not in their vocabulary, and this, in turn, depends on educating that audience before they ever enter a show or a gallery. The development of that audience is essential for the survival of artists, for artists’ ability to earn what their work deserves.

Equally important is the need to increase the availability of grants funding, directed not only to cultural not-for-profit organizations, but targeting the increasing population of creatives. The small grants that I received as an emerging artist served fundamental purposes; the money was welcome, clearly, and, less obviously, the recognition, by the granting agency, that my work was worthy. The latter, the affirmation of my work, was invaluable in convincing me I was on the right path.

To Art, is a verb, and, in order to art, artists need the specific space to do so. This is the most critical. I was lucky, I had a cellar to work in, though, in the winters I had to wear boots and a warm parka for many years until we could afford to add a studio space to our home. Yes, artists do suffer for their art. Subsidized combined studio/housing for artists would be a step in the right direction.

The lack of any of the above will never prevent a fully engaged, compelled artist from making her/his work. They would just make it easier and, perhaps, diminish the need for the cliche of the suffering artist.

Contact Info:

- Website: https://lindakayemoses.com

- Instagram: linda kaye-moses

- Facebook: Linda Kaye-Moses

- Linkedin: Linda Kaye-Moses

Image Credits

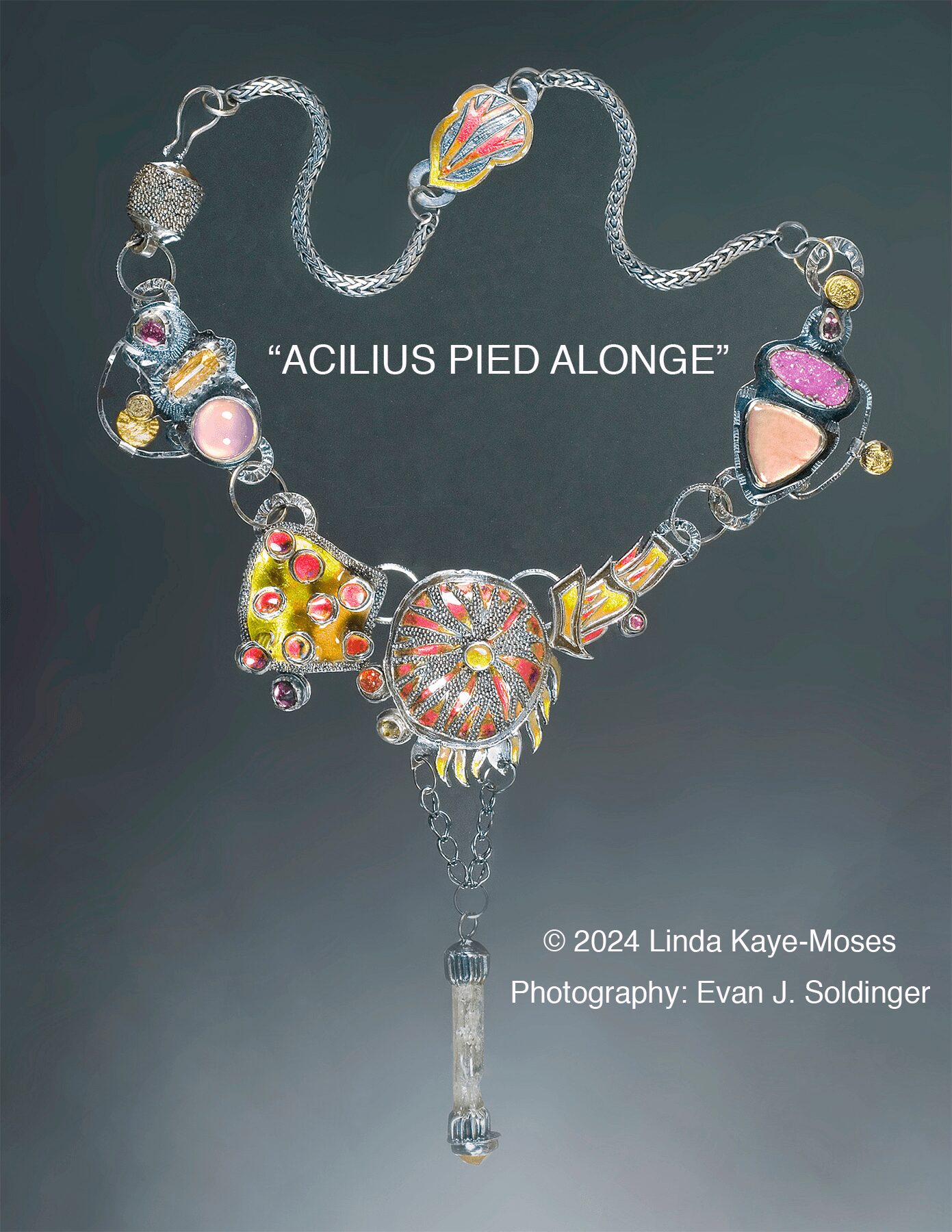

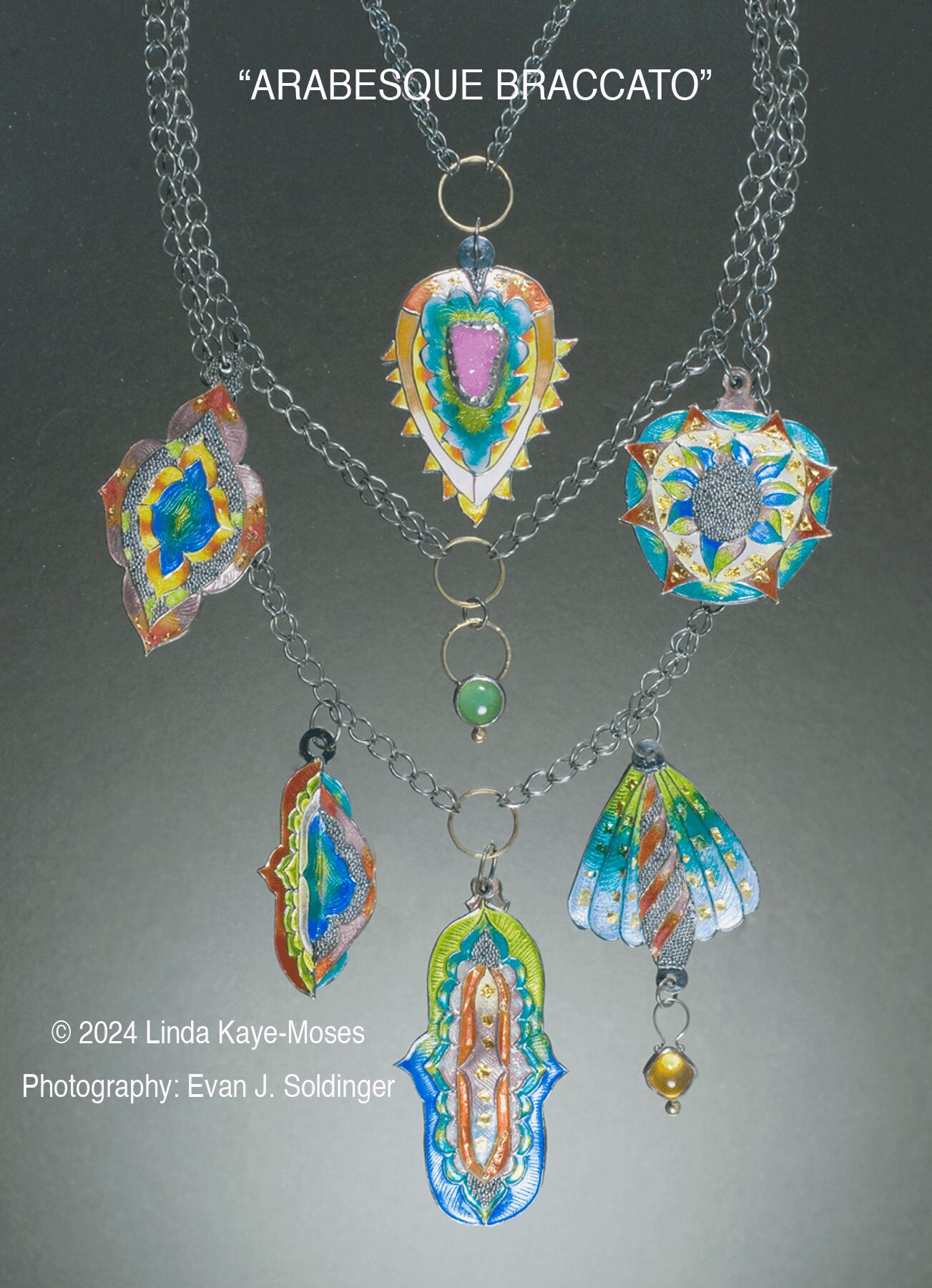

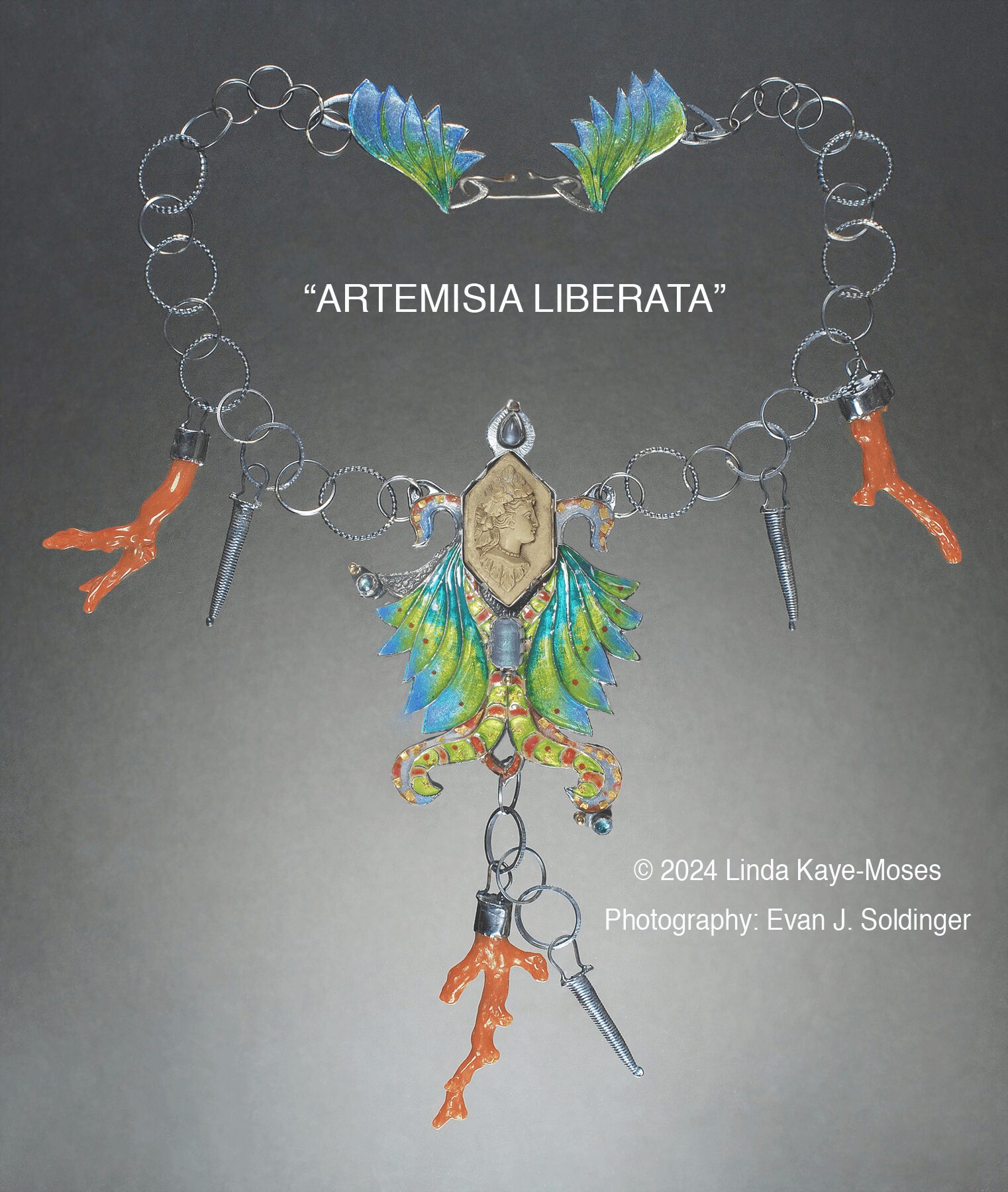

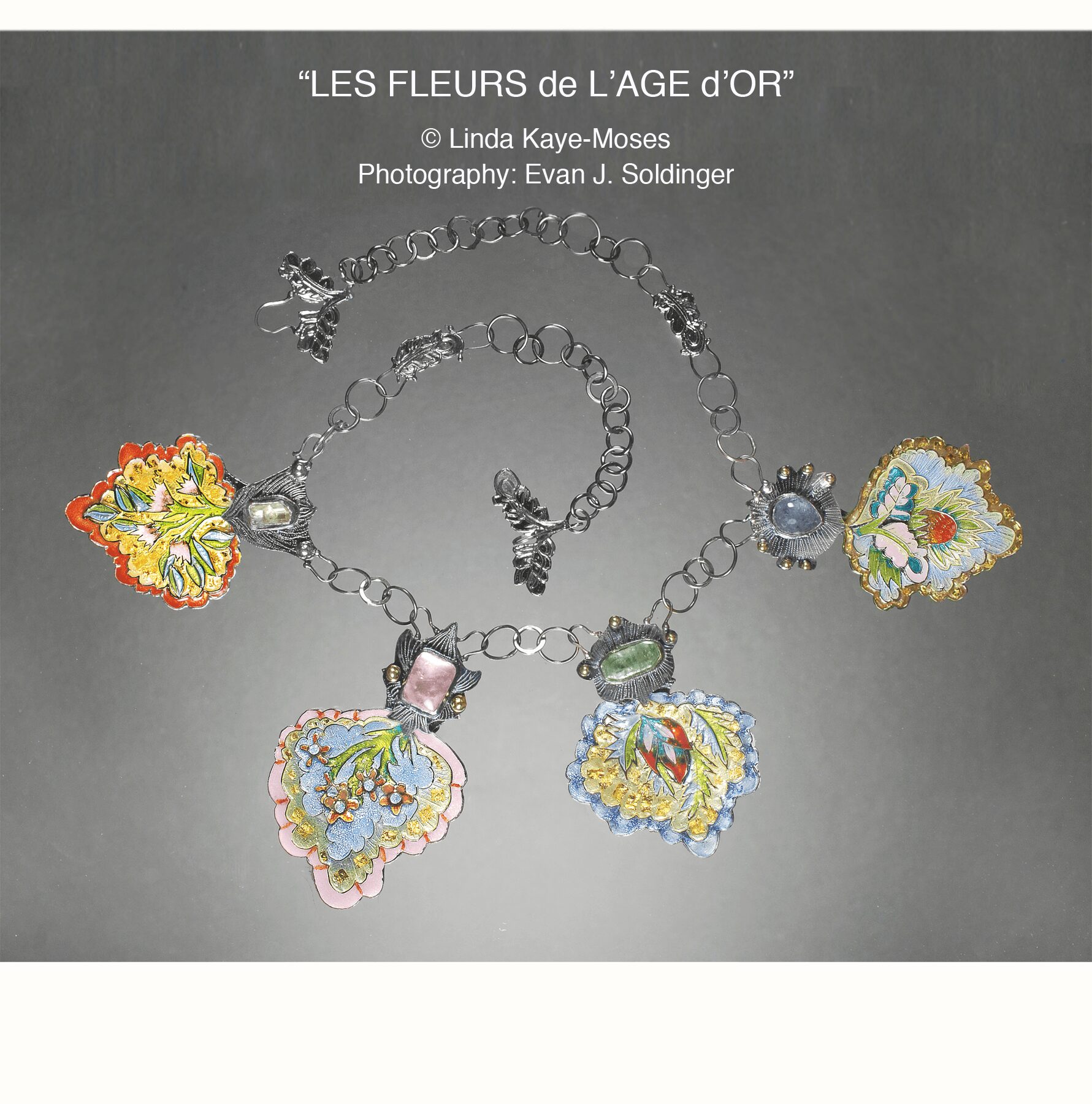

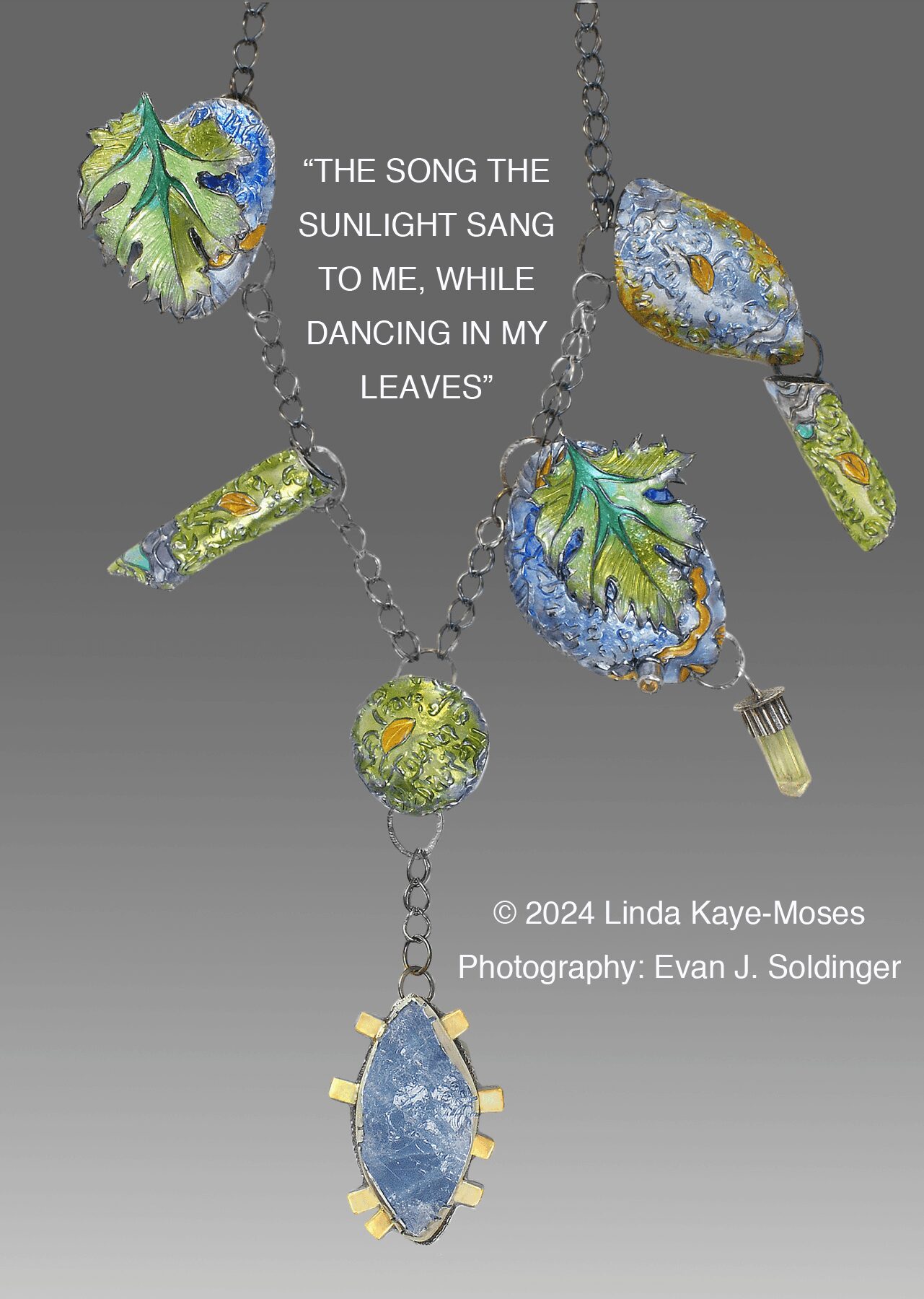

Photography: Evan J. Soldinger