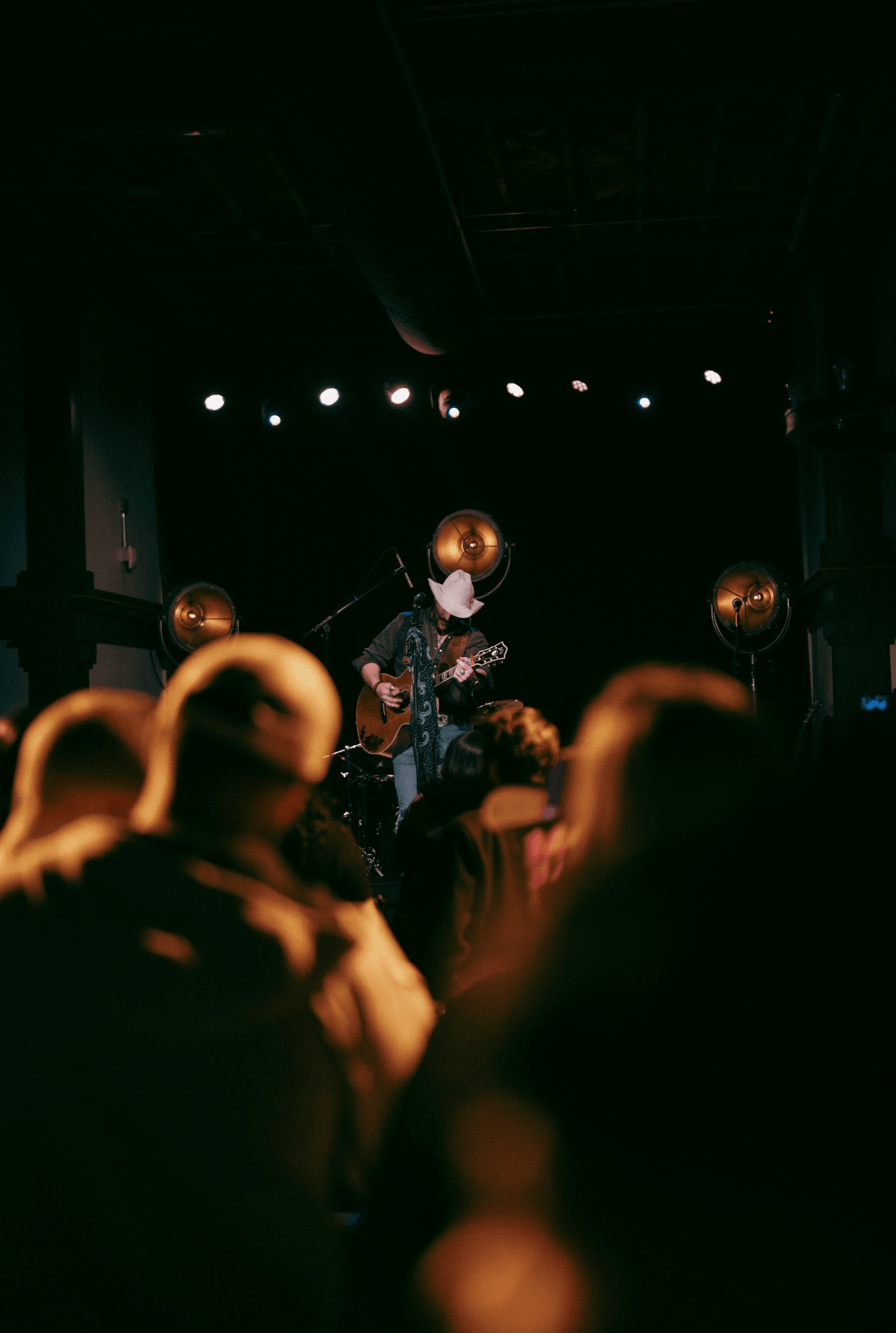

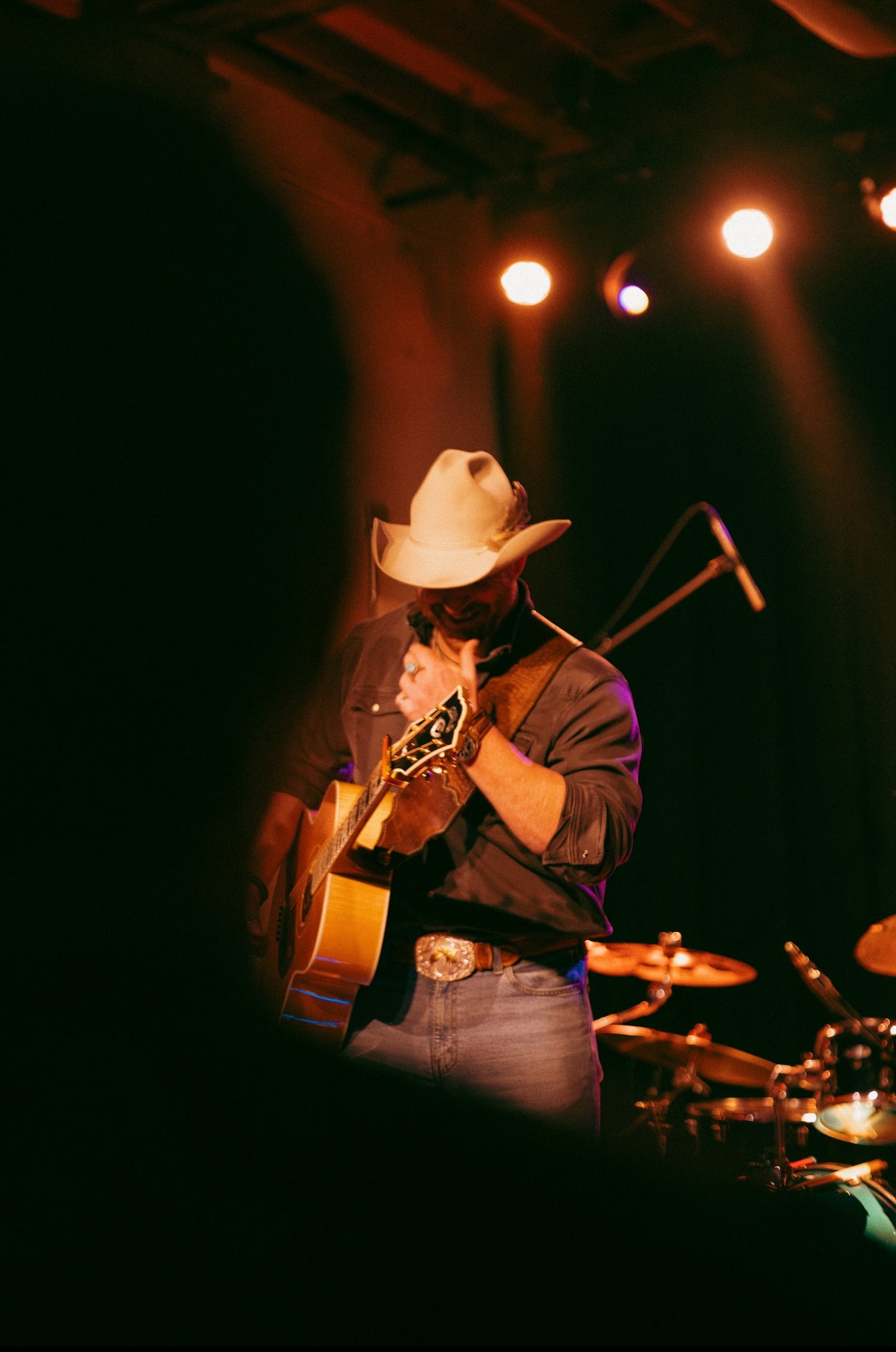

Alright – so today we’ve got the honor of introducing you to Levi Moore. We think you’ll enjoy our conversation, we’ve shared it below.

Hi Levi, thanks for joining us today. One of the toughest things about progressing in your creative career is that there are almost always unexpected problems that come up – problems that you often can’t read about in advance, can’t prepare for, etc. Have you had such and experience and if so, can you tell us the story of one of those unexpected problems you’ve encountered?

One of more challenging unexpected aspects of being a full time artist, and in my case, musician, is the amount of time that is required outside of performing. It takes many hours of practice to hone our creative skills to a level that they are worthy of being displayed, but also to make sure that they are marketable skills, and that they are an accurate representation of who we are as creatives.

When I began in music I jumped in feet first. I moved to Savannah, GA and had the idea that I wanted to play out as much as I could, but with no real idea of how to get started. The best thing I could think of was to spend a great deal of time in the local scene at open mics, going door to door, jam sessions, and things like that. Calls and emails are effective, but are a poor substitute for spending time in person.

As I picked up more gigs and began to get more momentum, that time shifted from simply being around people to needing to practice even more. The more venues I booked the more competition I was exposed to that required me to develop further as an artist, not least because I just wanted to feel like I was on par with my peers.

Next came the exploration into my live sound and the gear I used. It took a great deal of time researching what to get, how to use those tools, how to dial them in during a live performance, and, again, practice, practice, practice. As I continued building my setup into something I was proud of, I also continued to book more and more gigs, further and further out. Once more, I found that learning to manage my time was critical. One of the simplest things that a musician can do to be well-regarded as a professional is to just be on time. Show up early, get set up and soundchecked with time to troubleshoot, and then start the gig at the agreed upon hour. In order to do this, the further out I traveled for gigs, the more backwards planning I had to do. I needed to account for traffic on I-95, one of the most travelled routes in the country, especially in the summer months. Inevitably there will be accidents, slow downs, construction, or something, which I learned the hard way to always expect…if I took all of that into account properly, the worst thing that could happen was showing up a little too early.

Then there’s the time it takes to tear down, discuss the gig with the venue, and begrudgingly make that same drive back home. All in all, for a three hour gig that’s about an hour and a half away, I need to plan out at least 8-9 hours. Three for travel to and from, 2 hours for setup/teardown and discussion, and 3 for the actual performance, and thats assuming smooth traveling both ways. That was a learning curve that took a few mishaps to fully appreciate and begin to handle properly.

Another area of unexpected time consumption is in the studio, or wherever any artist spends their time bringing their art to life. Personally, my goal is a three minute song. To create that three minutes there are hours upon hours, days, and even weeks of discussion, recording, overdubbing, mixing, re-recording, mixing again and finally mastering. It’s amazing how much time goes into each little detail to achieve a fully produced final product. As a rough estimate, I would say that for each of my released projects there are at least 20 hours per minute of song.

The final time related issue that was hard to plan for is the amount of forward planning you have to do for vacations or trips or simple time off. Everything is on a schedule. My books, the venues’ books, any appointments on a day to day level, even the gym and groceries. Everything has to be factored in and time allotted so that you don’t get caught up short trying to make it to a gig on time, or complete a project or a commission as promised. The extra time, the hidden time if you will, takes a toll on relationships of all kinds as well. It can be difficult for people who are not artist or creatives to fully appreciate everything that goes into it, just as I can’t fully appreciate the level of training an astronaut has to do.

In my case, people see the 3 hour performance, but it’s hard to visualize the additional 5 or 6 hours that surround that show in order for me to be there at all, the endless of hours of practice at home, the creation of setlists and stage plots, and the countless hours of conducting business calls trying to market and land gigs and continue to build a platform from which to share music.

All of those things and I haven’t even broached the subject of social media, but that is its own realm entirely! I think all creatives and artists share a version of these difficulties that aren’t really on the surface.

As always, we appreciate you sharing your insights and we’ve got a few more questions for you, but before we get to all of that can you take a minute to introduce yourself and give our readers some of your back background and context?

My journey into being a full time musician has been an unexpected one. I was born in Savannah, GA and raised in places across the southeast corner of the country. I spent most of my time around horses, cattle, and football fields. I ended up going to high school in southern Missouris and attending Missouri State University on a full-ride football scholarship. Given my background, I chose to major in Animal Science-music was still not in the picture, at least, nothing more than a passing thought.

One of my teammates was also a roommate our freshman year, and coincidentally, a fantastic self-taught guitarist and general musician. I persuaded him to teach me my first 3 chords…the hallowed G, C, and D. As certain as I was that I was on the cusp on unlocking a long dormant and overwhelming talent, I was wrong. My fingers didn’t fit, my coordination was nonexistent, and my wrists were adamant that they should never bend that way for that long. Still, I learned enough to play an exceedingly simple strumming pattern, comprised mostly of G and C, that was certain to annoy anyone unfortunate enough to ask me if I played.

Soon, as classes and practice intensified, the raggedy red guitar became a dusty hat rack in the corner of the room. Sometime around my junior year of school, I became frustrated with the way my studies were going and that was amplified by some poor play on the field until one day I came home, looked over to the corner and my lonely guitar, and I decided then and there that I would teach myself to play. The learning commenced and I made reasonable progress until I decided I wanted to try and sing at the same time. The best thing that could have happened was that somehow the apartment next to mine was, and remained, vacant for the duration of my quite audible growing pains.

Quickly enough, the guitar began accompanying me to most places I went, with the obvious exception of practice and lecture halls. I continued to play and practice and got enough compliments to keep me motivated. One time in particular, in what was a formative moment, I was asked if I actually played and sang, to which I responded that I did, albeit not very well in either regard. She asked if I knew a particular song and naturally I proceeded to play it and a few others after which she said she would happily pay for a ticket one day. That was the single highest compliment I’d gotten to that point and the first hint of a thought crept in that just maybe music was something I could do.

My aforementioned teammate, my earliest maestro, was the one who first suggested that I go to an open mic. After a fair amount of deliberation, I did. I listed to several people play and thought to myself “I can do this!” I marched up to the signup sheet, put my name on the very last spot of the night, and sat back down wondering what I had just done. My name was called, I fumbled my guitar case open, and played two original songs I had written with all the grace and rhythmic flexibility of a reinforced steel girder. One song was ok, I only messed up a few words and got most of my changes right. The second song was a disaster, from my perspective. I mixed up verses with choruses and half of the second verse got put into the first verse; just a mess. Fortunately, while the song made absolutely no sense, it was an original so nobody knew the difference. After the adrenaline wore off and my hands quit shaking I distinctly remember thinking “Uh oh, I may have just created a monster.” From then on, I played every week at the open mic, and every chance that I could. I made my first dollar from music (which I still have in my lockbox) standing on the corner downtown busking and being a general nuisance.

Fast forward through graduation (B.S. in Animal Science: majoring in Beef Production with a Pre-Veterinary Medicine minor), and the solemn sunset of my football career (I won Defensive Player of the Game in my final game, so, high note), still playing and singing whether it was asked for or not, and I wound up working for a cattle ranch in southern Missouri and training some horses on the side. My musicianship had progressed to the point that I was able to play a few Friday and Saturday nights at some local hangouts that tolerated me and let me keep dreaming. During this time, I had a great friend and roommate that worked in the Oil and Gas industry. I was antsy and impatient, I needed some money, and suddenly an opportunity arrived. I interviewed for a company in Arkansas, packed my bags, said my goodbyes, and moved in the span of about 10 days.

I was blindsided. I had expected to continue playing my guitar on the weekends or whenever we got days off, but I quickly learned that was not a reality in that line of work. We worked so many hours and so many days that I didn’t even pick up my guitar for nearly 8 months. On a rare night off, I was out grabbing a drink with some friends and I ran into this fellow who, as it turned out, was a brilliant songwriter and musician. We struck up talk about guitars and music and writing until he eventually told me that he was hosting a songwriter night at a little venue near Little Rock, AR, and if I happened to be free, I should come down and play a couple. Through blind luck, we had another day off and so there I went. I muddled my way through a few of my songs, played a few other cover songs, and had one of the best musical times of my life. That lit a fire and I vowed right then to never let music slip away from my life.

I still had to contend with the amount of work I was doing though. Eventually I learned of this little bar in Little Rock called the Afterthought. On Wednesday nights they hosted an open mic and had a dazzling variety of musicians and poets and artists perform. I worked out an arrangement where I would text the man in charge the time I expected to be there, get home from work around 8:30pm, clean up and hustle to my truck to make the 30 minute trip to Little Rock, I’d run in and play my allotted 2 songs, hang out for a little while socializing, and then I’d drive back home around 1am, wake up at 4am, and go back to work. I did that every week for the next 2 years until I got out of the oilfield.

After that, I moved back to Savannah, GA to start a new chapter. I think I arrived on a Monday and by Tuesday night I was in Savannah at a new open mic. I met some incredibly helpful people to whom I owe a great debt and they taught me my way around Savannah and helped me land my first paying gig in town. From there, I focused on building my brand to be about quality music, being professional in all of my dealings, and being as reliable as possible. I’ve wanted to always maintain an attitude, and an appreciation, that while it’s a fun job it’s still a job and should be treated as such.

For the last seven years, I’ve been working as a full-time musician and singer/songwriter. I maintain a year round schedule of venues from St. Simon’s Island, GA to Dublin, GA to Hilton Head, SC and most placed between. As a writer, I like to focus on highlighting elements of the human condition and trying to connect to people in a relatable way, often attempting to showcase some sort of similarity that we can all share or recognize. My earliest musical influences were the songwriters of lore…Bob Dylan, Gordon Lightfoot, Jim Croce, etc. While my sound is decidedly country, more in keeping with the older generation of outlaw artists like Waylon Jennings and Johnny Cash, my songwriting skews more towards the storytellers and balladeers. I’ve been fortunate enough to have nominated multiple times as a vocalist and as a songwriter, culminating in being the 2021 Georgia Country Awards Male Artist of the Year.

Currently I am working on three different recording projects, two of which are being overseen by Paul Hornsby at Muscadine Recording Studios in Macon, GA. He has been widely recognized for many years as one of the preeminent producers for Southern Rock legends like the Allman Brothers, Marshall Tucker, and Charlie Daniels. Having the opportunity to work with and learn from someone with his vast breadth of experience is equal parts humbling and exhilarating.

The third project I’m focused on is being recorded by Adam Wyatt at Suntone Recording Studio in Savannah, GA. It’s a song that I wrote about Savannah simply for the love of songwriting and storytelling and the ghostly beauty of the city herself. It will be slight change of sound for me and is incorporating few other elements that I’m absolutely thrilled to put out into the world.

In your view, what can society to do to best support artists, creatives and a thriving creative ecosystem?

I feel like this is a subjective question, and prone to varying answers that are all tied back to who we are as individuals and as artists. That said, I will respond to it with an answer that rings true for me, but also others, at least from my experience. As we’ve moved forward into an increasingly technological age and existence, I believe that artists and creatives have been driven to create more and more consumable products; ie songs become used for reels, reels are used for commercials, commercials are used for larger products, etc. At each step, pieces of art become seen as a simply tool to create the larger vision and are often not recognized for their own merit. The shorter answer is simply appreciation.

As artists we all want to create experiences that people will enjoy, be inspired by, or stimulated in some way, as well as for our own expression. In order to do that, we must exist right at the edge of feeling appreciated or dismissed. It’s well known that musicians are obligated to play a lot of empty rooms on our journey, but we choke down that bitter pill in the name of paying dues, and often grow a great deal from having to push through the urge to quit or feeling that there is no point. It is amazing to me the monumental shift in perspective that happens when even one person stops to listen or compliment the music that we’re trying to share.

I’ve played gigs over the years where I really felt like no one was listening and they might even be happier if I was to just pack up and go home. I felt unseen, unheard, and thoroughly underwhelmed. Then, someone walks up and apologizes for not clapping and explains that they were listening and enjoying the music, but they were at dinner and needed to be engaged with their compatriots, which, of course, is as it should be. But that little moment of acknowledgement can change the entire complexion of the night. I’ve seen the shift when it was my turn to be in the audience or walking on the street and noticed an artist playing to a quiet crowd. I clapped, dropped a tip in the bucket, and complimented the work they were doing and immediately saw the look of relief and the renewed energy in their performance.

It can be a frightening experience to put ourselves on full and plain display with little to do but hope that people accept us and the pieces of ourselves we call our art. It’s a soaring high, exhilarating and inspiring, when a room applauds, someone purchases a piece of our work, or explains how our art spoke to them in a way we couldn’t have imagined. But it is a desolate low, bitter and depressing, when we step out onto that limb, full of hope, only to realize that perhaps we shouldn’t have bothered, or worse still, to be told point blank that we should give it up.

After those moments there’s the inevitable struggle to decide should we persevere or should we stop? Is the joy of expression worth the pain of rejection? It’s a cycle that never really stops. Often we choose to grow, get better, and try again-but sometimes the risk isn’t worth it any more. I think that is where society can step in and strive to be more aware of the full scope of the art that they see, hear, and consume. Not just what is tangibly in front of them, but also thinking about all that went into the creation of that piece, the emotions that are encapsulated in it, and the artistic souls that are hanging onto a thread of hope that someone will comprehend what they are struggling to convey. All of those hopes and fears and trepidations can be dealt with by the simple act of one person telling an artist that they appreciate them.

Learning and unlearning are both critical parts of growth – can you share a story of a time when you had to unlearn a lesson?

As a person, I have always been self-conscious. How I looked, what I wore, and how I thought that others perceived me. As an artist, that has been magnified ten fold. It’s a natural feeling-I willingly put myself on stage in front of people with a microphone and guitar, not exactly the route to take if you’re trying to be inconspicuous. What I didn’t realize is how large a detriment to my music those feelings could be.

Often, I’d go back and look at my performances and I’d noticed that I looked wooden or just plainly unenthused. I knew that to certainly not be true so I had to wonder why I might appear that way. Eventually it dawned on me that instead of being actually into the music and allowing myself to feel it and the energy from the crowd, I was instead distracted by my own thoughts about how I thought I was being perceived. It was a strange loop. I was having fun, so I wanted to make sure I looked that way, but I worried that it might seem that I wasn’t, and in the end it all came out as generally expressionless. A problem colloquially known as being too much in your own head.

I was worried about the mistakes I made singing, bad notes, missed chords, wrong lyrics and I was convinced that a single mistake from me would undo the entire experience for the crowd. It was a silly notion but as a growing artist, it was a real problem. To counteract that fear I doubled down on my focus, nailing the words, knowing the chords, trying to sing with perfection. It was a valiant effort, but it only served to hold me back. Because I focused so hard on singing everything without making mistakes it meant that I rarely took chances or pushed myself to leave my comfort zone with my voice or my guitar. The end result of that, despite it being for the best of reasons, was that much of my performance seemed far too similar and without passion. I felt passionate inside, but I wasn’t allowing myself to be vulnerable enough for it to show.

I carried those same issues with me into the recording studio. I’d get so focused on turning in the perfect, timeless, performance that I’d take myself completely out of the song I was singing. I’d be certain that I had nailed it only to come back and listen some weeks later and be horrified to hear that I’d completely missed my own mark. I had zeroed in on how I was singing something rather than why I was singing it.

The combination of those concerns left me with performances that seemed tired, flat, and as if I’d rather be somewhere else. None of which were true in the slightest but music is about communication and not so much what is said but how it makes someone feel. Essentially, I put myself up on stage, and then immediately build a wall between myself and the crowd because I wanted to be perfect for their sake, and to not make a fool of myself, but I was actively preventing them from feeling what I felt.

The revelation came when I heard a quote though I can’t remember where I heard it. It said “While artist hear something as their mistake, others hear it as the artists’ humanity.” It was simple quote, but a lightbulb moment. I then knew that I had to learn to allow myself to make mistakes and to take chances. It is something that I still struggle with on a daily basis when I perform, but it gets easier with time and effort. Obviously, as a professional, mistakes need to be minimized, hence the need for practice and preparation, but learning to give myself grace as a performer allowed me to connect with the crowd. I learned to give myself the same thing that they had been giving me the whole time and that alone was the important common ground I needed to build on. I’ve found that for my passion and conviction to come through, I need to allow myself to stand right on the precipice of what I can control. I had to learn to trust myself to be able to do what I wanted to do and if I missed it, oh well, laugh at it and go on. I am a person, after all, and not a jukebox.

Contact Info:

- Website: https://www.levimooremusic.com

- Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/levimooremusic

- Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/levimooremusic

- Twitter: https://www.x.com/levimooremusic

- Youtube: https://www.youtube.com/levimooremusic

- Other: Spotify @ https://open.spotify.com/artist/5CTSmf3RsNvztBauWsk9nT?si=M-wxZyPFSses7_CPki3FHg

Image Credits

James Maier