We were lucky to catch up with Laura Li recently and have shared our conversation below.

Alright, Laura thanks for taking the time to share your stories and insights with us today. We’d love to hear about when you first realized that you wanted to pursue a creative path professionally.

As a child with a stammer, I learned to grow a second tongue through art.

I drew, danced, held my grandmother’s stitching needles, and captured moments with my family’s point-and-shoot camera. Art became my primary language—my way of speaking with others and with myself. It was where I could shape my voice without interruption, without the weight of struggling to form a syllable aloud. Art was a sanctuary, a world I could build at my own pace.

I remember making a zine about my grandfather’s garden, a small patch of land he reclaimed from an abandoned public backyard once used for trash. I sketched the squashes, radishes, and all the greens I didn’t have English words for. I wrote about the time we spent there—his quiet dedication, the way his hands turned over the soil. I also wrote about my dreams, transforming them into video and installations. Dreams I longed to recount to my mother—like the one where she became a fox, then a whale, then longed to be a dolphin. I imagined what it would feel like to move through water as they did, the current brushing against my skin during swim practice. I once read that dolphins communicate through touch and song. What a wonderful world it would be if meaning was held not in spoken words but in the tenderness of everything else.

Now, I understand this more deeply through caring for my grandfather as he lives with dementia. Song and gentle massage have become our language—our way of reaching each other when words fall away.

My roots in art are my relationships—with my family, my people, and my community. Their patience, their dreams, their hands guiding mine as I traced Chinese characters and radicals. Art was never just an act but a way of holding time and space when speech felt impossible. Like a silkworm spinning its thread, I wove a cocoon—both as nurture and armor, a soft shield against the laughter of children who mocked my stammer and mispronunciations. Writing taught me to feel deeply, to see deeply, to move through the world with patience.

Great, appreciate you sharing that with us. Before we ask you to share more of your insights, can you take a moment to introduce yourself and how you got to where you are today to our readers.

I see myself as a kintsugi artist—one who mends and reimagines fragmented narratives and embodied knowledge, often eclipsed by institutions and colonial apparatuses. My work spans photography, video, oral history, archival research, performance, and community organizing, treating art-making as a process of weaving and stitching together a collective future.

My practice is deeply rooted in my relationship with my maternal grandparents, who taught me a queer feminist and diasporic lens of care. Their stories, gestures, and resilience continue to shape the ways I think about lineage, intergenerational transmission, and belonging. I co-lead two artist collectives centered on Sinophone-speaking queer artists, where we collectively explore themes of loss through war(s), intergenerational trauma, radical resilience, and healing.

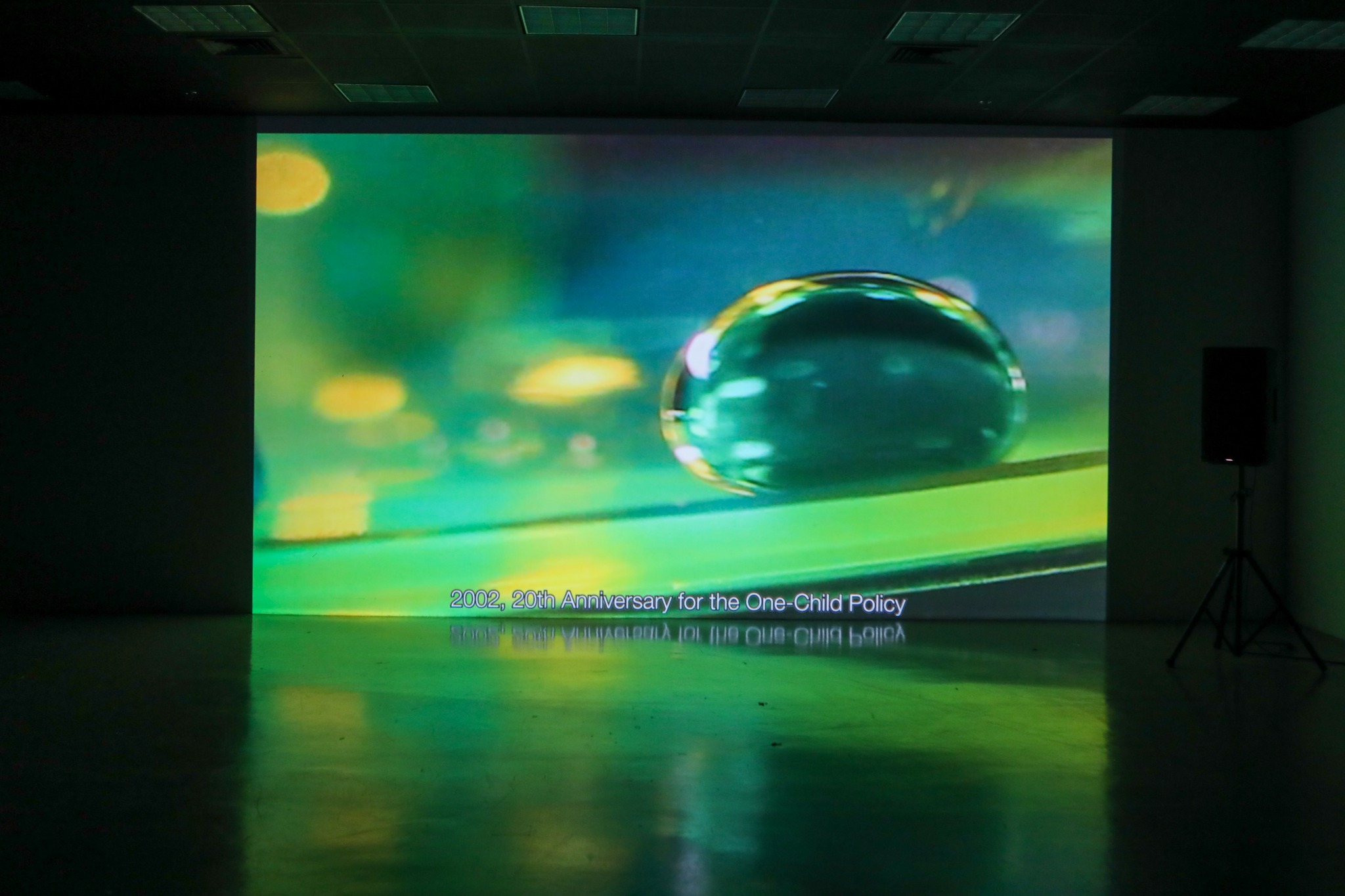

Some of my recent works include The (Ruins of) Ciba Shrine, an installation exploring sticky rice as a metaphor for entanglements and endurance, and Born/raw (2024), a film reflecting on the one-child policy in China and my own exploration of trans/non-binary fluidity in gender. Across my projects, I suture together familial archives, stop-motion animation, food-making, and ritual, creating gathering sites for healing and dialogue.

In my work, queerness and diaspora extend beyond identity check-boxes. They are fluid, malleable, and emergent energies—ways of being that, as feminist and activist adrienne maree brown describes, prioritize critical connections with oneself and others across time and space. My practice is shaped by the gathering-sharing traditions and gift-economy operations in my family in China, and I create work that reclaims once-rejected knowledge, including herbal medicine, acupuncture, and Buddhist and Taoist teachings, integrating them into contemporary artistic practice.

My work exists at the intersection of art, community, and activism—manifesting as screenings, public interventions, and performance-based rituals in parks and communal spaces. Embodied knowledge and intergenerational storytelling are central methodologies. Like the practice of kintsugi, which honors the visible scars of repair, my work does not seek to erase trauma but rather highlights the ruptures, reconfigurations, and emergent possibilities of resilience.

I also root my work in collective. One of these collectives is Chinese Artists and Organizers (CAO) Collective, a grassroots network of Sinophone queer feminist artists, organizers, and cultural workers spanning the U.S., China, and beyond. CAO Collective fosters artistic and political dialogues across borders, facilitating interdisciplinary collaborations, performances, and community-based art interventions. Through storytelling, participatory art-making, and knowledge-sharing, we create spaces where queer diasporic experiences can be archived, amplified, and honored. Our work is deeply engaged with themes of displacement, survival, and collective care, offering alternative ways to think about history, memory, and futurity outside of hegemonic narratives.

What sets my practice apart is this commitment to honoring brokenness as a site of transformation—inviting audiences and communities into spaces where memory, body, and history can be collectively held, repaired, and reimagined.

Are there any books, videos, essays or other resources that have significantly impacted your management and entrepreneurial thinking and philosophy?

Several books, essays, and artistic practices have deeply influenced my approach to management, community-building, and sustaining an artistic practice that is both ethical and impactful. My thinking is not rooted in traditional capitalism models but in collective care, decentralized organizing, and sustainability within art and activism.

One of the most influential texts for me is José Esteban Muñoz’s Disidentifications: Queers of Color and the Performance of Politics. His concept of navigating dominant cultural narratives through subversion, reinterpretation, and survival resonates deeply with my approach to art and organizing. As someone working within diasporic and queer communities, I see disidentification as a strategy not only for artistic expression but also for sustaining alternative economies and radical futures outside hierarchical institutions.

Adrienne Maree Brown’s Emergent Strategy has similarly shaped how I think about collaboration—especially within CAO Collective, where we work across borders and time zones. The idea that small-scale, intentional actions ripple into larger systemic change is something I return to often. I see this reflected in the ephemeral and relational works of artists like Lee Mingwei, whose meditative, participatory projects explore gift-giving, trust, and the intimacy of shared space. His exploration of dreams and invisible connections between people aligns with my own practice of weaving together memory, community, and storytelling.

Roland Barthes’ Mythologies has also been foundational in my thinking about the intersection of daily life, myth-making, and the role of artists in shaping cultural narratives. The way he deconstructs everyday objects and rituals to reveal their ideological underpinnings influences how I approach art as a form of reconfiguring dominant myths. I see my work as engaging with this tradition—unraveling state-manufactured histories and reassembling fragmented stories of migration, loss, and resilience.

Visually, I often return to Ocean Vuong’s poetry, not only for his language but for how he paints images of diasporic grief, love, and survival with such visceral clarity. His ability to turn personal memory into something universal, yet deeply rooted in queer and Asian experience, is something I strive for in my own work.

I also find inspiration in the work of Ana Mendieta, whose engagement with land, ritual, and the body as an archive of trauma and transformation echoes throughout my practice. Her Silueta series, where she imprints her body onto landscapes, reminds me of how art can reclaim erased histories and create new, embodied myths. Similarly, Shiota Chiharu’s installations—vast networks of red and black threads interwoven with objects—speak to the complex entanglements of memory, absence, and connection, themes that deeply resonate with me.

From the Philippines, David Medalla’s work has been another crucial influence. His “biokinetic” sculptures, like Cloud Canyons, reimagine materials in ways that feel alive, refusing static form. His conceptual approach to flux and impermanence inspires how I think about art as a process rather than a product—an evolving conversation between past and future.

At the core of my practice is also a deep engagement with classical Chinese thought and literature, particularly Zhuangzi’s Daoist philosophy, which teaches that transformation, uncertainty, and letting go of rigid categorizations are essential to understanding the world. Zhuangzi’s stories—of a butterfly dreaming of being a man, of useless trees finding longevity—challenge conventional hierarchies and offer a different approach to artistic and community work: one that embraces fluidity, contradiction, and the unknowable.

Similarly, I draw from the works of Tao Yuanming, the Jin Dynasty poet known for his deep reverence for nature and retreat from bureaucratic life. His poetry about farming, drinking wine, and finding joy in simplicity reminds me of the rhythms of my own family—of my grandfather’s garden, of the way knowledge is passed through hands rather than books, of art as something that is grown rather than produced.

Su Shi, the Song Dynasty poet and essayist, has also profoundly shaped my way of thinking. His ability to move between exile and court life, between ink painting and poetry, between humor and profound philosophical reflection, reminds me of the necessity of adaptability and resilience. His writings on art, nature, and impermanence resonate with the way I think about queerness and diaspora—not as fixed identities, but as shifting landscapes of possibility.

In my work, queerness and diaspora extend beyond identity check-boxes. They are fluid, malleable, and emergent energies—ways of being that, as feminist and activist adrienne maree brown describes, prioritize critical connections with oneself and others across time and space. My practice is shaped by the gathering-sharing traditions and gift-economy operations in my family in China, and I create work that reclaims once-rejected knowledge, including herbal medicine, acupuncture, and Buddhist and Taoist teachings, integrating them into contemporary artistic practice.

My work exists at the intersection of art, community, and activism—manifesting as screenings, public interventions, and performance-based rituals in parks and communal spaces. Embodied knowledge and intergenerational storytelling are central methodologies. Like the practice of kintsugi, which honors the visible scars of repair, my work does not seek to erase trauma but rather highlights the ruptures, reconfigurations, and emergent possibilities of resilience.

What sets my practice apart is this commitment to honoring brokenness as a site of transformation—inviting audiences and communities into spaces where memory, body, and history can be collectively held, repaired, and reimagined.

Is there mission driving your creative journey?

My artistic practice is guided by the experimentation of different media, the use of public space, and engagement with themes to expand diaspora and queer agency. Through building rituals and critically reflecting on cultural histories, my work functions as deviations, distortions, and reimaginings that resist assimilation into white colonial culture and values. As a diasporic artist working in the U.S. with roots in China and Japan, my creative journey is driven by the need to navigate the entanglements of history, identity, and place—moving beyond a U.S.-centric or Orientalist framework that often flattens the richness and contradictions within these relationships. I seek to hold space in art for critical relational building through reciprocity, complexity and nuances.

At the core of my practice is the belief that art is not just a means of expression but a mode of relationship-building—both with human and non-human entities—a way of reimagining and caring for communities beyond conventional structures. I am particularly drawn to spaces that foster dialogue, where questions do not seek singular answers but instead circle and dance with one another. My practice builds upon communal rituals, ancestral knowledge, and the act of gathering, creating sites where historical ruptures can be acknowledged, and alternative futures can be imagined.

For me, the work of creating is inseparable from the work of listening. Spaces where conversations unfold—where accountability, contradiction, and transformation are held rather than flattened—are the ones I am committed to cultivating. This is not about pointing fingers or erasing differences; it is about co-building infrastructures of care, fostering continued dialogue, and creating sustainable ecosystems where abundance is rooted in intimacy, relationships, and shared imaginaries.

I am constantly reflecting on what it means to steward both art and community in times of crisis—particularly in the face of ongoing global violence, displacement, and environmental degradation. Some of the questions that guide me include: What does it mean to create with others—including human and non-human forces? What structures do we need to sustain our work collectively? How do we work and create at the pace of care and healing, rather than extraction and exploitation?

My commitment in the coming years is to actively shape collective spaces where these questions can be lived and practiced. To me, artistic practice is not just about professional development; it is about cultivating a long-term ethic of care, listening, and intentional leadership so that our stories, our communities, and our solidarities continue to thrive beyond any single moment or institution. I see my work as part of a broader movement—one that weaves together knowledges, builds momentum, and co-nourishes a future where artistic and communal resilience are deeply intertwined.

Contact Info:

- Website: https://www.lauradudu.com

- Instagram: lauradudupersonal

Image Credits

Image 4 credit:Sebastian Bach

Image 5 credit: photo credited Laura li, Kathy ou, albus

Image 6 credit: junting

Image 7 credit: yi fan