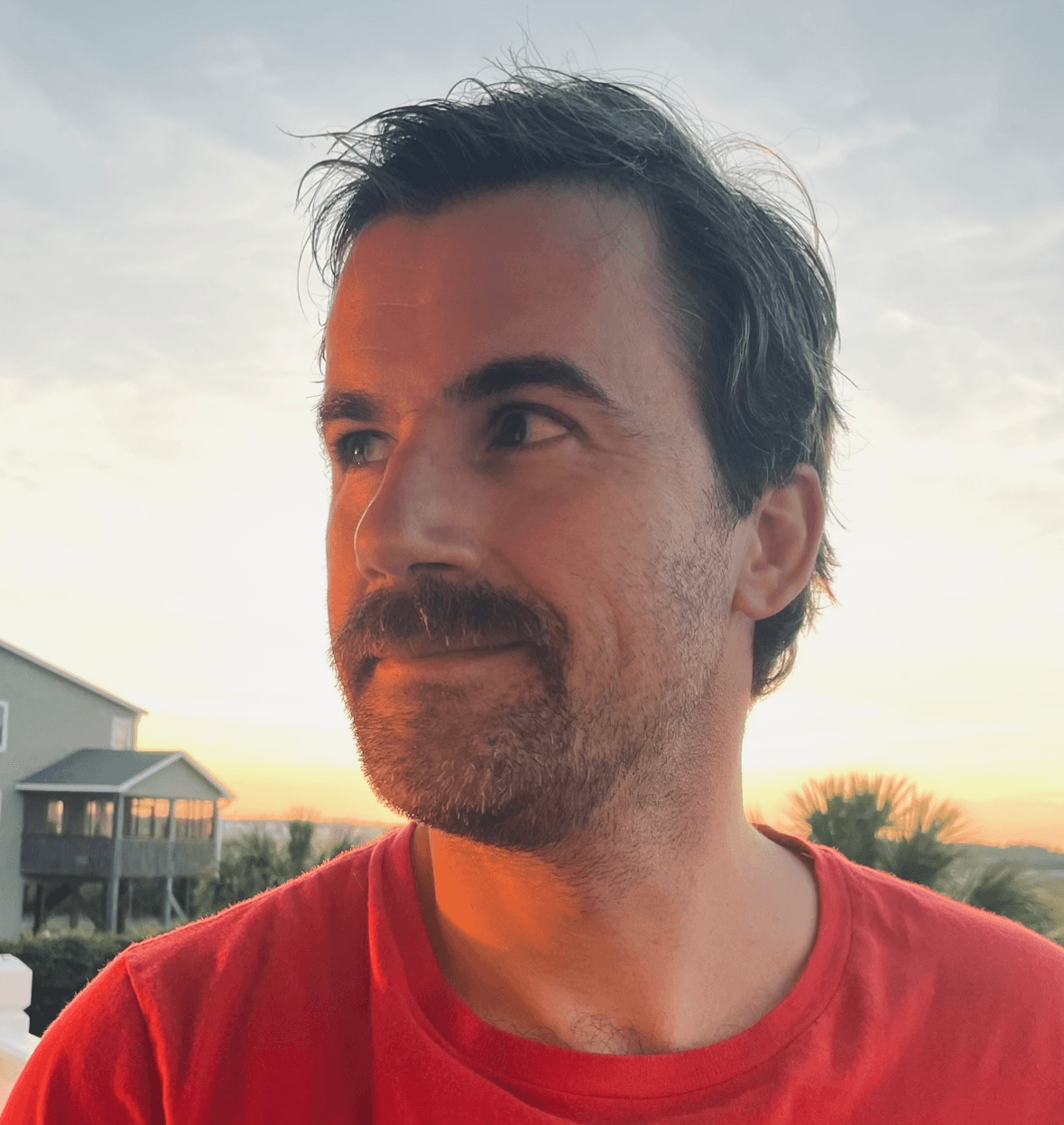

We’re excited to introduce you to the always interesting and insightful Larkin Ford. We hope you’ll enjoy our conversation with Larkin below.

Hi Larkin, thanks for joining us today. Learning the craft is often a unique journey from every creative – we’d love to hear about your journey and if knowing what you know now, you would have done anything differently to speed up the learning process.

I have drawn since I was a kid, so I thought I had a certain level of aptitude by the time I started my undergraduate studies at UNC Asheville. Once I was there, I realized how little I understood about how to compose images, how to take reference photos and use them skillfully, and how to analyze the human figure—gesture, structure, and anatomical details—to create compelling figures in charcoal or oil paint. Virginia Derryberry had a huge impact on my understanding of light and color, and she enriched my understanding of how to imply narrative and symbolic connections between human figures.

I had another humbling and instructive moment when I entered graduate school and began working with Ralph Gilbert. His background in animation and public murals gives him a strong focus on silhouette as a starting point for all drawing and painting. I worked with him on a huge mural for the Lilly Library’s Reading Room, and that experience has informed the compositions of my subsequent work.

What skills are essential? I think it’s vital to start by drawing still life materials. That way, you can get started with proportional sighting—measuring the height and width of your setup—and getting comfortable translating the three-dimensional world into the two dimensions of the page or canvas, without working from a photo, which is already flat. Linear perspective is huge—it can be tedious to learn, but folks who are otherwise talented will trip over it for their entire careers if they don’t bite the bullet and learn how to use vanishing points. For a figurative painter like me, some understanding of the human form is important, and I have found that life drawing is essential to sharpen those skills. If you intend to use color, it’s helpful to know some color theory and a workflow for color matching—including a focus on the value (lightness or darkness) of the color. It’s freeing to diverge from strict realism, but I find that some curiosity about the world as it is, and some interest in learning about its complexity and variety, keeps the act of art-making challenging and exciting.

I often ask myself what I wish I had learned decades before I did. Then I boil it down and put it into my drawing and painting classes. Since it helps me immensely to see how others plan and execute their work, I’m starting to film myself working on paintings, and will put some on YouTube by the end of summer.

Awesome – so before we get into the rest of our questions, can you briefly introduce yourself to our readers.

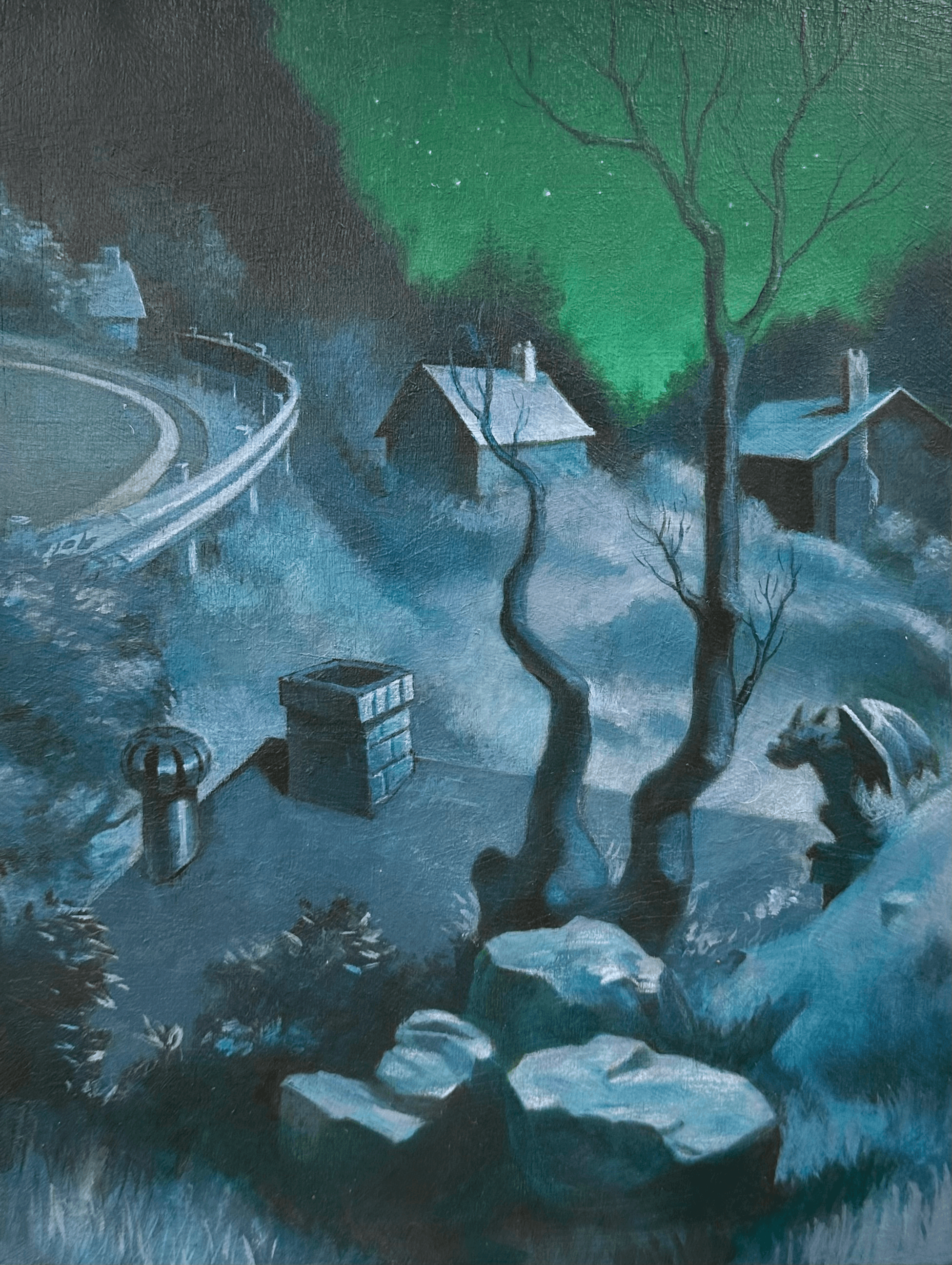

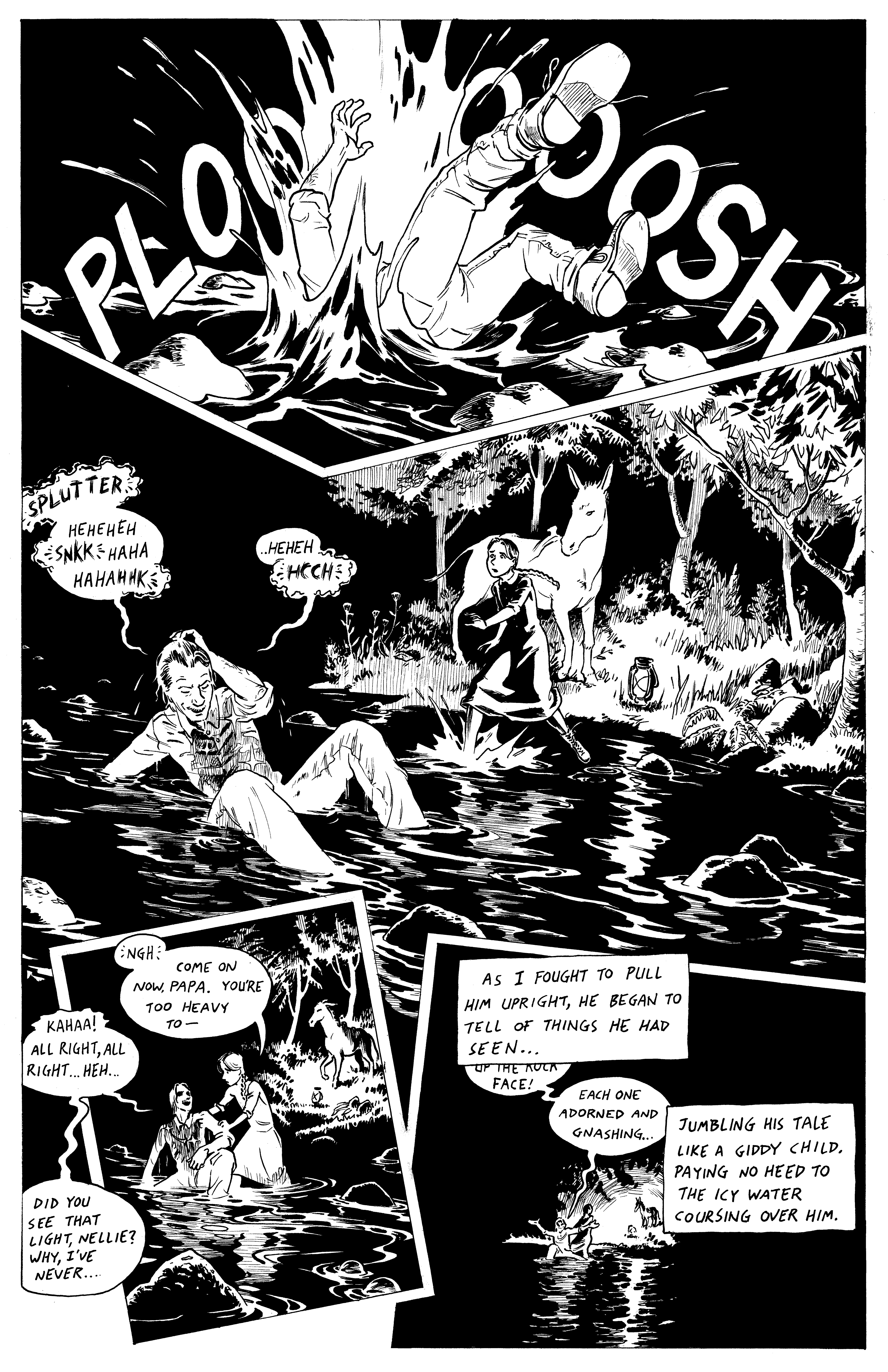

I create figurative paintings of Southern Gothic desolation and splendor, and I write and draw comics. When people choose to buy my paintings, read my comics, or hire me for illustration or mural projects, they do so because my perspective on the world resonates with them. When I educate others, I work hard to equip people of all backgrounds with the formal skills to express their own perspectives more vividly, and to create an environment where experimentation and exploration are welcome.

In my studio practice, I strive to create work that feels urgent and true, and to find others who value what I do. My work tends toward the grimy, the dilapidated, and the grotesque, and I soften that bleakness with visual beauty and injections of gallows humor. It’s a beautiful thing when we can keep our struggles in perspective, hold the yawning void at bay, and aim for gratitude over cynicism, curiosity over resignation.

We often hear about learning lessons – but just as important is unlearning lessons. Have you ever had to unlearn a lesson?

I’ve had to unlearn some of the firm divisions between art and illustration that I have been taught, explicitly and implicitly. It’s still difficult for me to reconcile the gallery world with the publication world, and I’ve all but stopped trying to put my graphic novel art on display in galleries. Plenty of artists I admire, and plenty of my closest artist friends, have no interest in comics as an art form, and similarly, lots of fans of sequential art aren’t gallery-goers.

It should be obvious that creative folks need to cultivate different audiences for our various forms of output, but I think of all my work as so closely connected that I’ve been slow to wise up. I’m finally realizing that all of your work has to be assessed on its own merits, and that sometimes, a person who doesn’t enjoy one aspect of your creative practice just doesn’t enjoy that genre or mode of making. It’s not that you’re necessarily bad at playing polka, it’s just that the fans of your metal band aren’t all going to be on board.

What do you find most rewarding about being a creative?

The most rewarding aspect is also the scariest. If we choose to be fiercely vulnerable and honest, and if we work hard at this art thing, we can share some essential aspect of ourselves with anyone who wants to tap into it. It’s misleading to call it communication, but there’s some transfer of experience happening. The isolation in the studio can feel almost sacred since the potential for a deeper and stranger communion is always there. The scary side of this vulnerability is that, the longer your reach extends, the more people will encounter your work and be indifferent or hostile to it. I’m still hustling in obscurity, so this is easy for me to say—but I believe it’s easily worth the risk.

Contact Info:

- Website: https://www.larkinhford.com

- Instagram: @larkinford

- Youtube: @haddenfordanimation7370

- Other: You can reach me at [email protected] to say hello, or to join my mailing list.