We were lucky to catch up with Kiran Balakrishna recently and have shared our conversation below.

Kiran, thanks for taking the time to share your stories with us today Let’s jump right into how you came up with the idea?

In architecture, ideas rarely arrive fully formed. They take shape quietly – through observation, patience and a willingness to let a place speak before you begin speaking for it. Every project starts as uncertainty, and the concept gradually emerges when you start listening to the site, the people it holds and the feeling the space is meant to carry.

The site is always the first storyteller. Its geometry, its shadows, the way sound moves through it – all of these reveal intentions long before a plan exists. Then comes the human dimension, imagining how someone might move, pause or gather. And finally, there is the emotional tone of the space – the atmosphere someone senses long before they understand its form. When these layers converge, the idea begins to surface.

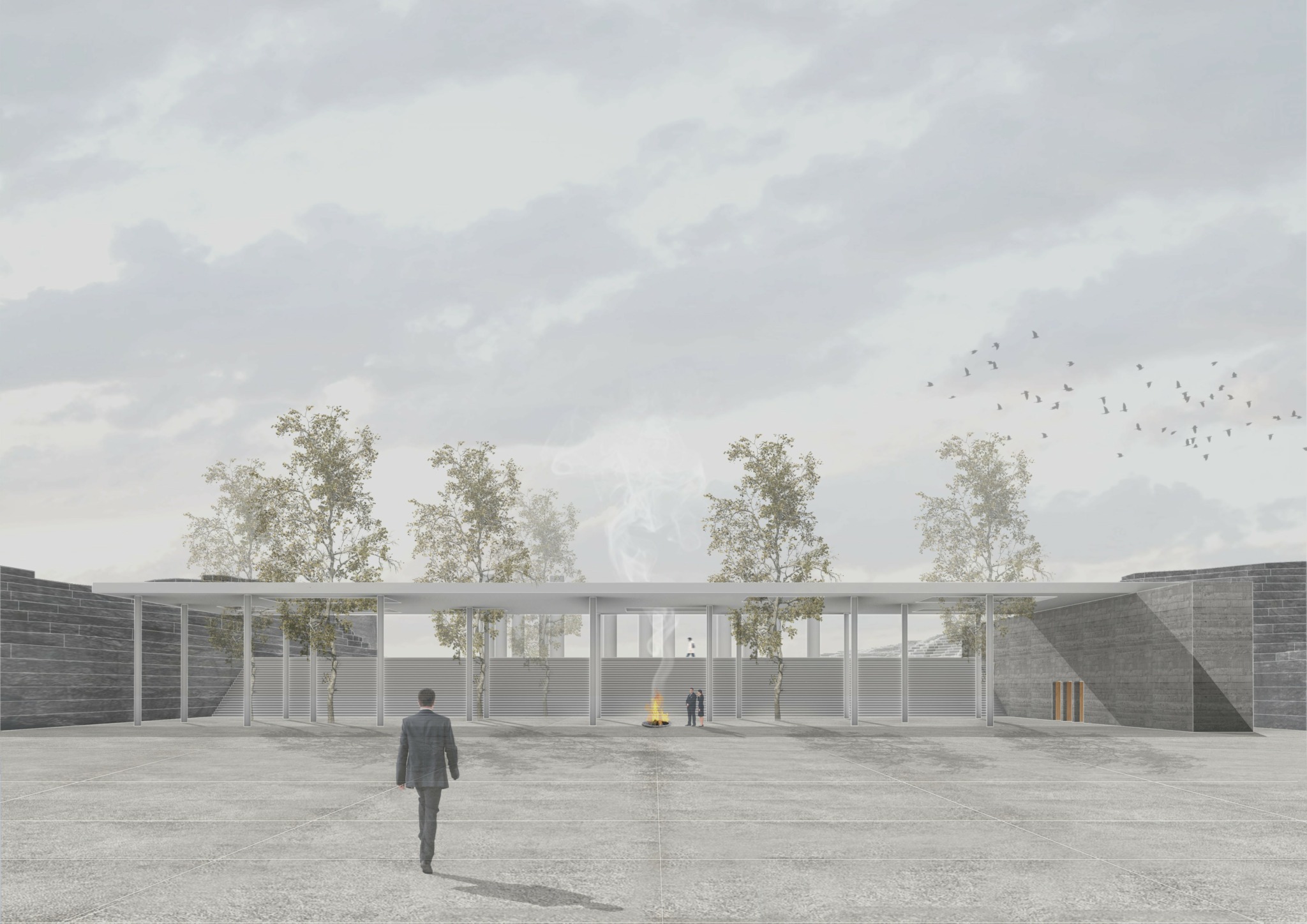

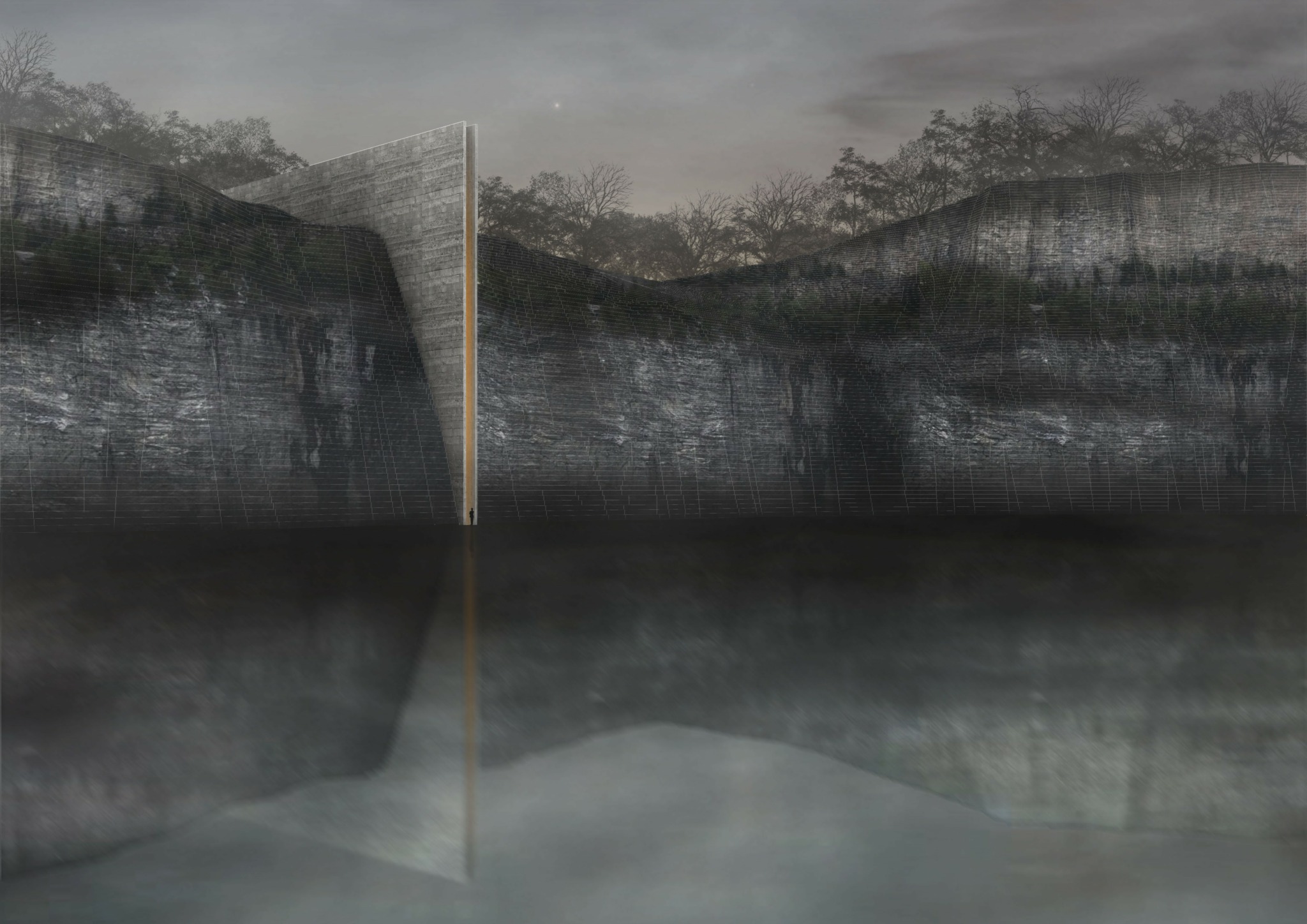

My project ‘The Three Rooms’ grew from this kind of unfolding. It is a conceptual columbarium designed within an abandoned quarry in Atlanta – a setting where memory and quiet reflection belong naturally. Designing for that kind of emotional landscape called for restraint and a sequence of spaces that guide gently rather than announce themselves.

When I first stepped into the quarry, I didn’t have a direction in mind. I remember the feeling more than the moment – the cool air, the stone rising around me, the way the outside world felt suddenly distant. The space didn’t ask for attention. It created stillness. That became the starting point of the design.

I understood quickly that the architecture shouldn’t sit above the quarry. It needed to feel as though it originated from within it – shaped by the land’s weight, time and imperfections. That perspective set the tone for everything that followed. A columbarium requires a certain humility, and the quarry already knew how to hold that emotion.

As I spent more time in the space, the design naturally evolved into three rooms – Reflection, Meditation and Celebration. The quarry didn’t feel like a single gesture. It felt like a slow inward journey. Each room became a chapter, allowing someone to shift from introspection to stillness and eventually toward light again.

The site kept offering direction.

The stratified stone suggested the material language.

The narrow passages invited tall, quiet openings to the sky.

The acoustics asked for simplicity rather than drama.

And the daylight revealed how each room wanted to feel.

Some early versions conflicted with the place, but refining them only brought the design closer to the quarry’s rhythm.

In the end, the concept felt uncovered rather than invented – shaped by patience, close attention and an openness to let the site lead.

That slow unfolding is what shaped the project, and honestly, it’s the part of architecture I enjoy the most.

Kiran, love having you share your insights with us. Before we ask you more questions, maybe you can take a moment to introduce yourself to our readers who might have missed our earlier conversations?

I’m an architectural designer who has always been drawn to the question of why certain spaces stay with us long after we’ve left them. Early on, I realized I didn’t remember places for their objects- I remembered how they shaped a moment: how a space could quiet everything around me, how a material choice could give a room its sincerity, how a transition could shift the mood without ever calling attention to itself. Those impressions didn’t just influence my thinking; they’re what led me to choose architecture in the first place.

In my work, I start with the emotional intention of a space. I study how architecture guides people without instruction- how movement is shaped by scale, how thresholds influence the mind, how light or material can create ease. For me, experience comes first, and the design grows from that understanding.

Professionally, I’ve worked across a wide range of large-scale projects: healthcare campuses where clarity matters deeply, airports shaped by flow and choreography, residential high-rises guided by rhythm and light, and science & technology buildings defined by precision. Across these typologies, my focus is often the same- translating a design vision into something coordinated, buildable and true to its original intent. I enjoy the moment where conceptual thinking meets technical reality.

What sets me apart is the balance I hold between emotional sensitivity and technical discipline. I design from the inside out, beginning with how a space should feel for the people moving through it, while understanding the rigor required to deliver complex buildings at scale. That combination allows me to carry an idea from early concept to construction without losing its essence.

At the center of my work is a simple belief: architecture should create presence. A good space steadies you. It strips away what’s unnecessary so you can meet the moment clearly. If someone walks through a place I’ve shaped and feels more anchored- more aware of themselves or their thoughts- then the architecture is doing what it should.

That pursuit- designing environments that resonate through experience rather than appearance- is what defines my practice and keeps me committed to the craft.

We often hear about learning lessons – but just as important is unlearning lessons. Have you ever had to unlearn a lesson?

One of the most meaningful lessons I had to unlearn was the assumption that my own perception of space could stand in for someone else’s experience. Early in my career, I relied heavily on intuition- the atmospheres that felt calm to me, the proportions I found grounding, the transitions that made sense in my own internal logic. Those instincts weren’t wrong; in many ways, they’re part of what makes me a designer. But I eventually realized they couldn’t be the only lens I used.

The backstory is simple: I was working on a residential project where I felt confident in the direction I was taking- one that felt serene and intentional to me. But when I walked the clients through the design, their reactions shifted everything. The calm entry sequence I had envisioned didn’t match the natural tempo of their household. The areas I shaped for privacy weren’t where they instinctively sought comfort. And the kitchen- which I organized for clarity and flow- didn’t reflect the way they cooked, gathered or moved through their day. My instincts weren’t wrong; they simply weren’t tuned to the rhythms and realities of how they lived.

That experience taught me something I carry into every project now: my own perception is a tool, not the destination. It helps me read atmosphere, anticipate emotional tone, and make decisions with intention- but the design only becomes meaningful when I step fully into the user’s world. Their routines, their thresholds of comfort, their sense of openness or privacy- those truths matter just as much as my architectural sensibility.

Unlearning the idea that my instincts should lead, and replacing it with the belief that they should inform, changed how I practice. It made my work richer, more empathetic and more precise. Architecture isn’t about projecting my experience onto others- it’s about shaping a space where their experiences can unfold naturally and feel deeply their own.

Have any books or other resources had a big impact on you?

Louis Kahn’s work has shaped my ‘design’ philosophy more than any book or lecture ever has. What I learned from him wasn’t technique- it was a way of seeing. Kahn approached architecture as something to be uncovered rather than invented, and that idea changed how I think about space.

My time at the Kimbell Art Museum made this clear. Inside that building, the essentials- light, proportion, material- carried the entire atmosphere. The concrete vaults didn’t try to impress; they created a quiet awareness. The light wasn’t dramatic; it simply revealed the room with patience. That restraint taught me that architecture doesn’t need to be loud to be powerful. It needs to be honest.

Kahn also instilled in me a respect for material character. His idea of asking a brick what it wants to be sounds simple, but it holds an entire philosophy: materials aren’t just chosen, they’re listened to. That mindset continues to ground my work.

And his understanding of ‘served and servant spaces’ shaped how I think about sequence and emotion- that architecture isn’t just about rooms, but about how you move between them. That clarity influenced projects like The Three Rooms, where transitions matter as much as the spaces themselves.

What I take from Kahn is a belief that simplicity is not minimalism, but resolution- the point where a space feels inevitable. That idea continues to guide how I design and the presence I want a space to hold.

Contact Info:

- Website: https://www.kiranbalakrishna.com

- Linkedin: https://www.linkedin.com/in/kiranbalakrishna1