We’re excited to introduce you to the always interesting and insightful Kevin Michaluk. We hope you’ll enjoy our conversation with Kevin below.

Kevin, looking forward to hearing all of your stories today. We love asking folks what they would do differently if they were starting today – how they would speed up the process, etc. We’d love to hear how you would set everything up if you were to start from step 1 today.

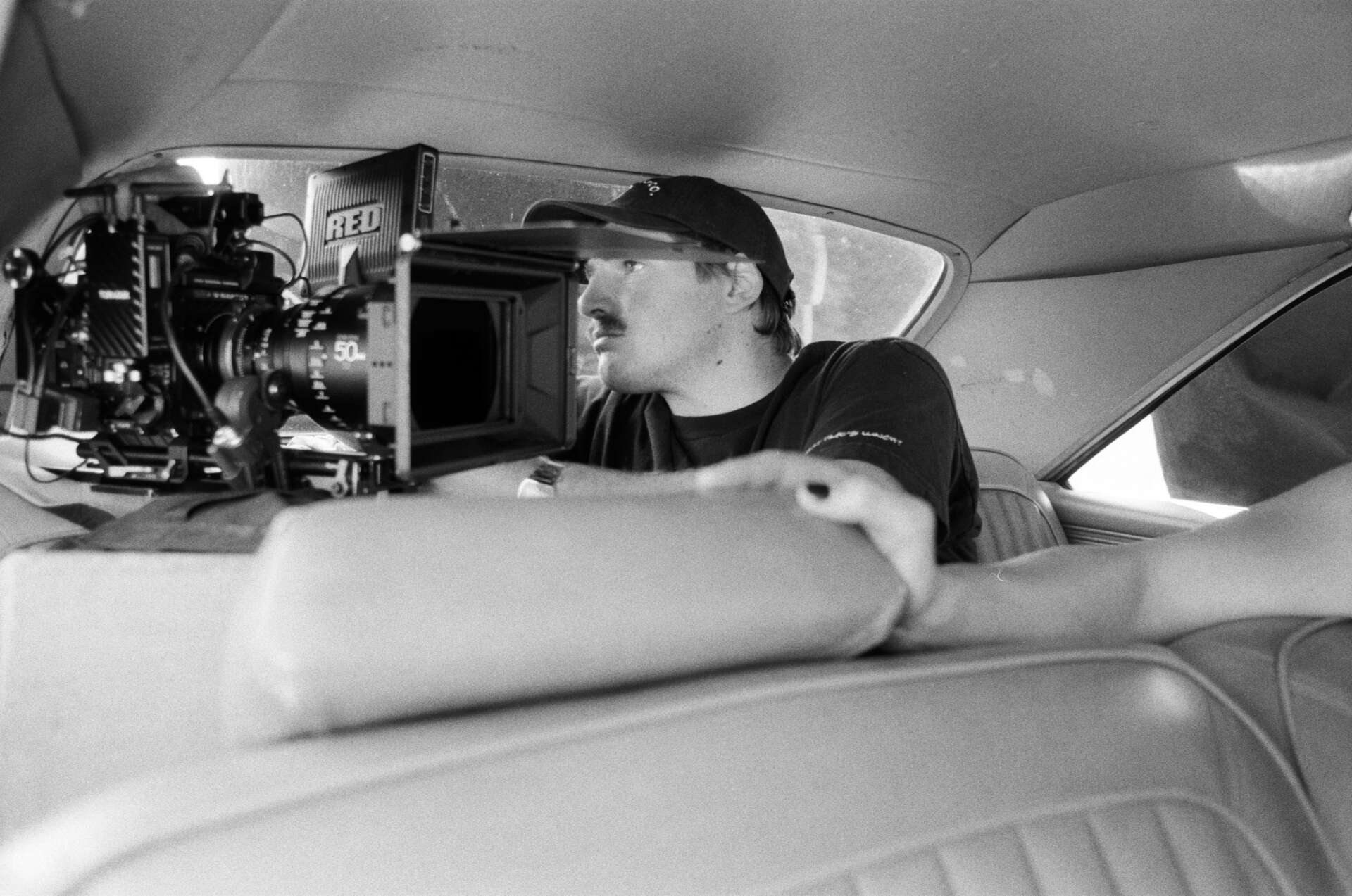

When I reflect on what I’ve done in my career to this point, if I were to wish I had done anything differently, what comes to mind is surprisingly the opposite of what you might think. Working in film is a marathon, not a sprint. In today’s instant-gratification, influencer age, it seems the top priority for creative professionals is to reach certain positions as soon as possible. The cinematographer, or director of photography, position, after director, might be the top role people tend to sprint towards now. When I first started working in the industry, I split my time between camera assistant and lighting department jobs. I took an unconventional route toward DP work, in that I took an extended break from the industry altogether after I moved to Portland, and jumped right back in when I started working for a local creative agency a couple of years later. It didn’t take long for me to serve as the company’s staff DP, and I’ve been almost exclusively working in that capacity, freelance as of 2021, ever since. If I could change one thing, I wouldn’t get to where I am any quicker. In fact, I’d get here much slower. Efficiency to quality, not rank.

To elaborate a little more, you are only as good as the people you surround yourself with. In terms of volume of productions under their belt, the director, more often than not, may be the least experienced person on set. When you consider how much goes into each project, it’s hard to see how any director would have the capacity to take on more than a couple of projects per year, if that. As a DP, I should be more experienced than the directors who hire me. Aside from certain exceptions, I should be able to take on more projects than any director, just as my gaffer, key grip, and other crew should realistically expect to work more often than I do. This is all to say, when you’re not at the top of the food chain, you work a lot more, and the more you work the more you learn. I know I still have so much to learn, but I don’t work on as many projects as when I was working as a gaffer or a grip. Just food for thought.

Kevin, love having you share your insights with us. Before we ask you more questions, maybe you can take a moment to introduce yourself to our readers who might have missed our earlier conversations?

My name is Kevin Michaluk. I was born in Maryland, just outside of Washington, D.C., where I lived until I was twenty. I moved to Los Angeles to attend film school, but it was kind of just an excuse to move to LA without any money to my name. I learned a lot during my time there, and wouldn’t trade it for the world, but ultimately concluded that LA was not the place for me. Awhile later, I found myself in Portland, OR without a single contact or friend in town, but I made it work over time. When I first arrived, I thought my LA experience and can-do attitude would yield instant success, but it took much longer than planned. It quickly became more about making money to survive than living my dream, and I knew I needed a “normal” job. After applying to well over a hundred jobs, and my bank account dwindling, I took the first thing I could get–working as a terminal operator at a Union Pacific rail yard. While earning my keep, I eventually started getting some commercial gigs, and was able to leave the manual labor job. It wasn’t much later when I began working on staff for a local creative agency. At the agency, I quickly became their in-house DP, and spent almost six years shooting every project they landed. It was a great opportunity to be so involved in a company’s creative identity, while contributing to their culture on other levels. While still working there, in spring 2021 I went into business with a friend and industry peer and opened a studio and equipment rental house in Portland called Framework. A handful of months later, I left the agency and went freelance full time while continuing to grow my own business.

As a cinematographer, I pride myself not only on my creative ability, but my leadership qualities. It is simply not enough to pick up a camera and take pretty pictures. In order to be a successful DP, you must understand how to tell stories, manage people, problem solve and plan, and demonstrate a strong grasp of visual fundamentals. When you reach a certain level, you don’t need to know how to navigate a menu or get into the technical pitfalls of various camera systems. You need to know how to communicate intent and lead others to facilitate the vision. These are things that bring me joy, and that I feel particularly skilled at.

What do you think helped you build your reputation within your market?

Up until I was maybe twenty-eight years old, I was much more of an introvert. I shuddered at the idea of networking. Not only was it intimidating, but it also went against my idea of how things should work. I’m still not entirely sure of what that idea was, but I knew then that I simply did not like talking to strangers, especially about things that could impact my future. It wasn’t until I paid $20 to attend a speed-networking event in Portland when I forced myself to change how I viewed such events. After nearly going home without having spoken to a single person, I paused to establish a thought experiment. Imagine you are someone who does well in this type of situation. Ok, that’s easy to visualize. Now, what if you could just pretend to be that person? Play a character, and that character thrives in social settings. I know it sounds overly simple, but it worked. I went into the event and pretended to be someone who was confident and comfortable talking to total strangers and I didn’t die, so that encouraged me to continue. From there on out, I didn’t let nerves stop me from approaching and talking to industry folks, and many doors have opened as a result. Building a reputation takes time. I didn’t suddenly establish one just because I decided to talk to people at an event. However, your reputation is really just the sum of several interactions with many people. I pay attention to who people are, and what influence they may have over the local industry. I singled out those people, and decided that I would introduce myself, by name, every single time I saw them, until they started calling out to me by name. Eventually it happened, and I could stop introducing myself. Simple but effective.

Do you have any insights you can share related to maintaining high team morale?

Managing a team is not always easy. There are many personalities and approaches to this work. It’s important to make people feel valued, and I’m a collaborative person, so I want everyone to walk away from a project feeling a sense of ownership, like they put their stamp on whatever their role was. On the contrary, sometimes there isn’t a whole lot of room for collaboration. In those situations, I try to provide my team with as much information as possible, share my ideas and plans, and break the job up into more bite-sized tasks so no one gets carried away and everyone can get involved. Without micro-managing, it’s important to establish yourself as the source of all information, so when someone completes a series of duties, they come back for more. You are the coach of a team. You can rally that team into a winning mindset, but that doesn’t mean you get to sit back and relax. You have to steer them to victory, until the last second on the clock. Things are often difficult on set. Sometimes morale can take a dip. It all starts at the top. If I start moping around, my crew is going to take a hit. How can I expect them to perform when I’m showing displeasure on set? There’s a saying for a reason–the show must go on. As a leader, it’s crucial to stay positive and keep pushing forward. I’m not perfect. Sometimes things get to me, and people can tell. When I’m short with someone, or maybe a bit too direct, I always make a point to chat with my crew afterwards and express to them that we have plenty of laughs and fun times on set, but sometimes, when it’s crunch time or whatever, things can get intense, and it’s all for the love and passion of what we’re doing. Nothing is personal, and it’s essential that my crew understand that in order to work well with me. That brings me to an important talking point of leadership–accountability. I learned early on in my career that if you wrong someone in front of others, you have a responsibility to make up for it in public, not in private. You cannot pull someone aside to apologize. You must address it in front of other people. If you pull them off to the side, you have robbed them of their dignity without restoring it in the eyes of their peers. In the end, genuinely caring about the people you work with goes a long way.

Contact Info:

- Website: kbmichaluk.com

- Instagram: instagram.com/kbmichaluk

Image Credits

Photos by Jonathan Robinson, Yasmeen Magar, Caitlin Callahan, Kevin Dyer