We’re excited to introduce you to the always interesting and insightful Ken Slesarik. We hope you’ll enjoy our conversation with Ken below.

Alright, Ken thanks for taking the time to share your stories and insights with us today. Can you tell us a bit about who your hero is and the influence they’ve had on you?

My wife, Julie, and I had been enjoying the festivities at a holiday party in 2019 when suddenly a clear and intrusive thought shook me: “Kenny is dead.”

I knew our son Kenny was safely at work at the convenience store where he clerked on Friday nights. So, I pushed this unexpected and unwanted thought from my mind.

We left the party and decided to stop at the store where Kenny worked. I couldn’t escape the sinking worry, and I had to see him. The attendant said Kenny hadn’t shown up and was 30 minutes late for his overnight shift.

I kept telling myself not to panic. I called Kenny from the car as we drove home. He didn’t answer, and I left an urgent voice message on his phone. My hand was shaking so much as I attempted to end the call. My thumb missed, so his phone was still recording as I said, “I think he’s dead!”

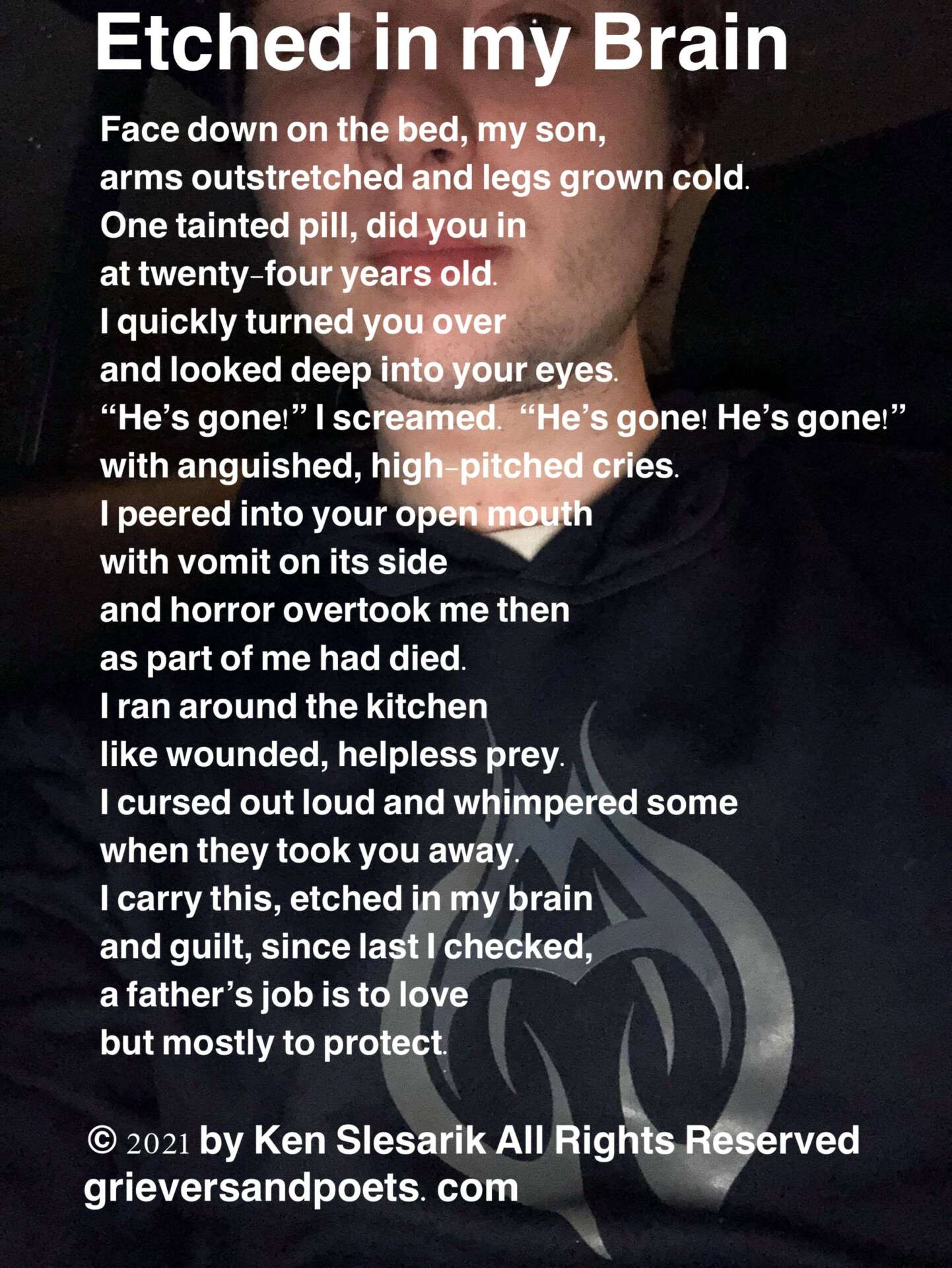

When we reached home, Kenny’s door was locked, and his phone was ringing. Julie reassured me, saying he’d probably just overslept but I knew better. I screamed, “He’s dead!” Then we broke open the door. Nothing can prepare you for what we found.

My world was shattered when I entered the room. Kenny lay face down on his bed. I frantically turned him over to perform CPR even though I knew he was gone. I looked into his open eyes and mouth, and I heard myself scream several times, agonized and high-pitched, “He’s gone! He’s gone!”

One pill was on Kenny’s nightstand when I found him. According to the police investigation, he was having back pain from unloading trucks at his work. They learned he had reached out to someone who knew a guy who got him two counterfeit pain pills. The other pill that killed him was laced with a fatal dose of fentanyl.

In the early months after Kenny’s death, I started having horrible anxiety attacks. Being in crowds suddenly became unbearable. I developed high blood pressure that was constant. The trauma altered my hormone levels, and my testosterone went from high-normal to very low. I put on 28 pounds of depression weight. Life became a struggle.

Every two months or so, I’d have life altering flashbacks along with physical pain and fear for my safety. The “fight or flight” response would last for hours and rendered me helpless. It was truly horrific.

I realized I had three options. I could commit suicide, become a recluse or put one foot in front of the other and do something to change my circumstances.

I began searching for meaning in the pain. Heroes started to emerge. I attended therapy and grief groups. I read dozens of books. I rediscovered writing in general and poetry, in particular. It helped me process the hurt.

I am a special education teacher. When I went back to work, the love and support from my school community was heroic indeed. The administration hired a substitute teacher to work with me for many weeks so I could leave my students to cry and grieve, if needed. And I did.

Another hero, the leader of my men’s grief group challenged me. “When you see Kenny again, what are you going to tell him you did with all that pain?” he asked. The realization that my son would want me to figure things out and even thrive gave me meaning and purpose.

My mother and my wife have both been with me in the darkest of times. Their love and support have sustained me when I thought I was broken beyond repair. Like all great women, they are true heroes.

Grief is not linear. It is an up and down, back and forth journey. Despite all the support from my heroes, I reached a point where I didn’t want to continue living. I couldn’t take the relentless grief and anxiety. And I needed to be with my son.

I remember the moment I formed my exit plan. I retreated into our closet to cry. I rationalized that my family would understand and ultimately be okay. I started crafting a note of love and goodbyes to them. By the following afternoon, I would be gone. I was at peace with this decision and went to bed.

I have no idea if I’d become unhinged that night because of my grief. But what happened as I lay in bed could not have been more vivid and real. As I slept, in that pitch-black room, I heard Kenny say, “Dad!” His voice was loud enough to wake me but not loud enough to scare me.

Confused, I turned toward Julie. “Did you hear that?” I asked. But my wife was asleep and only stirred a bit.

I was now wide awake. I clearly heard Kenny say, “Please don’t hurt yourself.” That was it. His words came in much the same way as the thought I had had at the party. It was very clear and unmistakably Kenny’s voice and sort of generated near my ear. I lay there crying and realized suicide was no longer an option.

In his death, Kenny has become by biggest hero. He is the reason I’m still here. My love and appreciation for him have grown tremendously since his passing. I strive to live in a way that will honor him and make him proud.

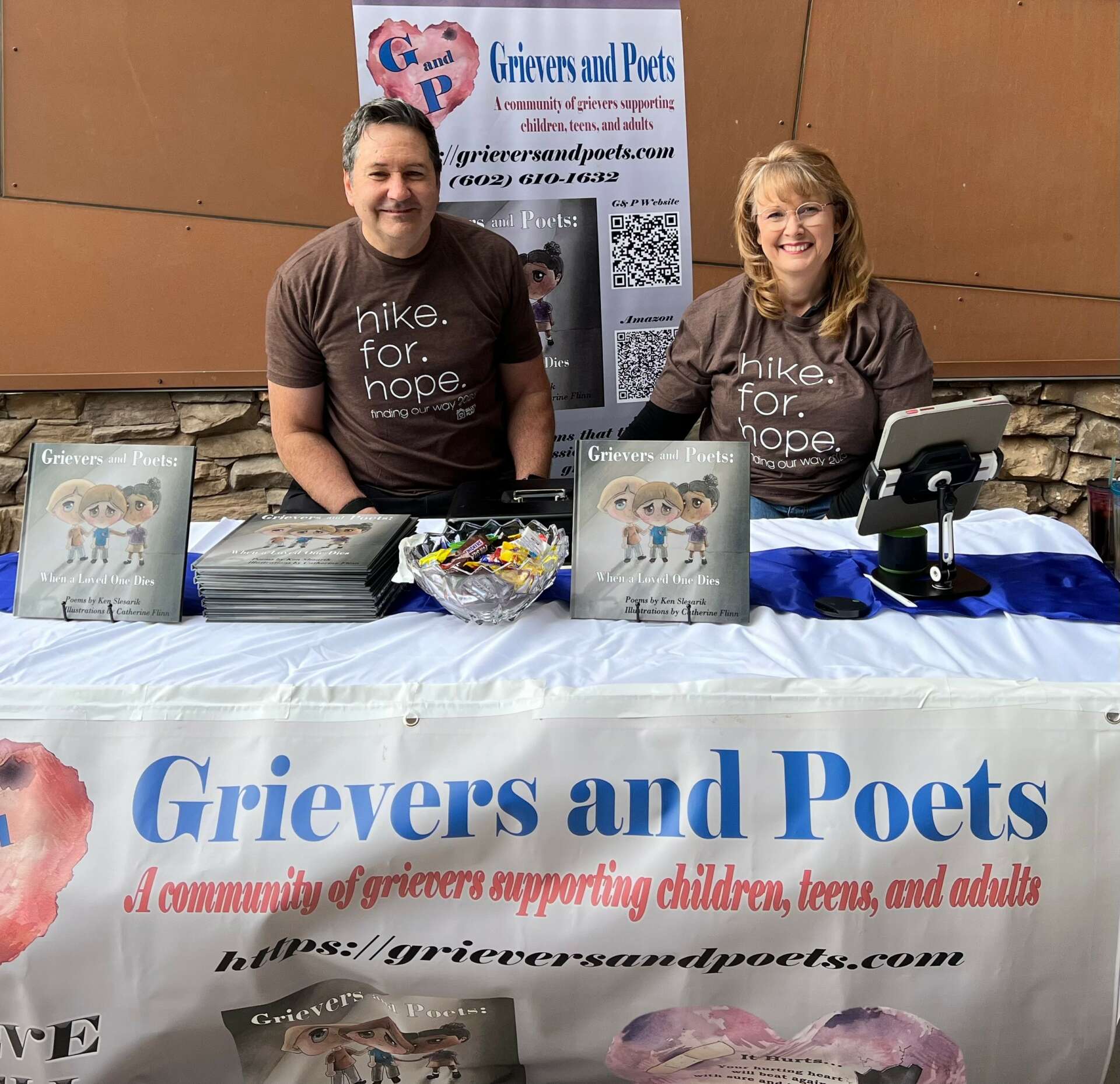

One way I hope that I’m honoring him is by founding “Grievers and Poets” to help children, teens and adults who grieve. We published our first grief book for children with others on the way. For many years prior to my son’s death, I wrote poetry for children and did a well received assembly program that has now been adapted for families who have lost a special person(s).

Our plans include other books and resources for those that grieve. I believe you need to experience the pain to process your grief and I hope to continue to find ways to help others.

None of this would have been possible if it weren’t for the heroes along the way who have helped me navigate my grief.

It has not been easy, but I have found that my greatest source of pain has also become my greatest impetus for growth. I will never be the same person I was before Kenny died. Rest assured, I will continue to press on and find ways to integrate my loss.

My advice to those who are grieving is to look for the heroes. They are there to help you when you are ready to ask yourself, “Is there anything good and positive in my situation?” I fully realize that is a tough question to ask.

I would do anything to have my son back. Yet, there is no denying that my love and empathy for others have grown since I lost him. When I talk to loss survivors or write a simple grief poem for them, I feel their pain and I weep with and for them.

Ken, before we move on to more of these sorts of questions, can you take some time to bring our readers up to speed on you and what you do?

After the death of our son, my wife and I founded “Grievers and Poets” as a way to help those that grieve. I wrote our first collection of grief poetry for children and put that out into the world. It has resonated with people of all ages and counselors are using it in their practice. I had written children’s poetry for years prior to his death and this is a way for me to process my own loss and use whatever creative talents I have to heal.

Currently, I speak twice a month to civic groups and other organizations. I also do a grief sensitive, family-friendly assembly program that explores the pain of loss. We laugh, we cry and we love. In the past, I was a co-facilitator of a men’s grief group and I did one on one grief companioning for a short time. I have realized my energies are best suited to writing and speaking until I have more time to expand our mission after I retire from teaching in two years.

Our second book is near completion and the long range goal is to have twelve books for grievers. We will see how that progresses because I have a high standard for quality writing and I don’t want to be redundant in my work.

Ken Slesarik is a special education teacher, children’s poet and grief educator from Phoenix, Arizona. He is the author of the children’s book “Grievers and Poets: When a Loved One Dies.” His poems have been published in many anthologies and he regularly hosts poetry programs for students. Ken has spoken at conferences, written poetry curricula, and enjoys providing professional development for teachers. Ken’s mission is to empower those who grieve through the healing power of poetry.

What’s the most rewarding aspect of being a creative in your experience?

I have always enjoyed writing and children’s poetry has been my focus for over a decade. Writers will often speak of those moments of flow and a peak creative state while practicing their craft. I certainly have experienced those moments but nothing quite like when writing my first two poetry grief books for children. I was openly mourning the loss of my son. I felt every raw emotion while writing even the simplest of rhyme.

For the better part of two years, I experienced severe anxiety. The fight or flight response would last for hours as I sometimes rocked back and forth and begged God or the Universe to kill me. I would have flashbacks of the moment I found my son and interacted with his body.

On one occasion while driving, my brain went into grief overload, and I suddenly had no recollection of who or even what I was. It was as if was driving a car that I had never been in before. I started to panic and did not recognize my own name on the car registration. As I stared into the rereview mirror, all I saw was a middle-aged man that I couldn’t place or recognize. I noticed a phone that had fallen on the passenger side floorboard with a screensaver picture on it. I thought this handsome kid must have been important to me and then after a few minutes my reality came flooding back.

Writing became my solace during this time, and I entered that state of flow and peak creative state easier because I was grieving. This may sound tacky or uncouth but I usually start the writing process by opening a sealed plastic bag that contains an unwashed basketball jersey of my son, Kenny. When I breathe in the faint, yet pungent smell I start to feel the love and the pain of his absence at the same time. This puts me in a frame of mind where I’m really not concerned with writing anything “good” or publishable. The result, for me, is a much higher percentage of solid first drafts and that of course is when the real work begins.

Those creative moments are the most rewarding aspect of being a children’s poet for me. It’s sometimes painful but also beautiful as I feel connected.

Is there mission driving your creative journey?

I have learned to find meaning in the death of my son. I did this by continually asking variations of the question “Is there anything good about my situation?” At first, I was appalled at such a notion, and I answered with a string of expletives. Once I decided I was going to live, I started to slice it thin and find the good and see glimmers of hope.

I have a friend who is humorous on a comedic level. He told a spontaneous joke and I smiled and laughed. It was the first such moment since my son died. In those few seconds I wasn’t depressed or crying, and I was grateful for our friendship.

I used to think there is absolutely nothing worse than losing a child. It is never helpful to make comparisons to other people and their grief, but I met a man who lost two children. I felt a profound empathy towards him and an overwhelming thankfulness that other people in my life were still here.

There are others who have endured all kinds of horrendous situations and I’m not comparing myself to them, but I feel there must be a reason I’ve experienced such overwhelming grief and chaos that was condensed in a relatively short period of time. It must be for some greater good in the end.

It’s moments like those mentioned above that drive my creative journey but the overriding question that really drives me is “What story am I going to tell Kenny when I eventually see him again?”

I choose to believe this, and it drives me. Did I become permanently wounded and give up? Did the depression and PTSD leave me helpless and stuck? Or did I find a way to honor his memory and help people realize that it is okay to be broken but it’s not healthy to remain that way.

Contact Info:

- Website: Grieversandpoets.com

- Instagram: Ken Slesarik (@grieverandpoet)

- Facebook: Grievers and Poets

- Twitter: Ken Slesarik @grieverand poet

- Youtube: Ken Slesarik (Children’s Poet)