We caught up with the brilliant and insightful Keelan McMorrow a few weeks ago and have shared our conversation below.

Keelan, thanks for joining us, excited to have you contributing your stories and insights. Do you feel you or your work has ever been misunderstood or mischaracterized? If so, tell us the story and how/why it happened and if there are any interesting learnings or insights you took from the experience?

Quite frequently, actually. The thing about art is that it’s always open to interpretation. I mean, anything offered up to the masses for consumption is, I suppose, but in art there is anything but a general consensus in a post-modern world. So an artist has to develop a fairly thick skin early on in order to take criticism constructively, to know where it’s coming from, to decipher well-meaning criticism from toxicity, and so on. But more to the point, the vast majority of artists spend exorbitant amounts of time alone, working, compared to the average population, and so sometimes otherwise banal comments or observations can be taken out of context by an artist who’s been living and breathing that work for days, weeks, years. So you have to learn to communicate on a different level, in a sense, to wear two sets of shoes, and to accept that nobody else out there is living your life and making your art but you. Because if you’re really doing art, that’s the thing that’s become your life, and you can’t expect every single person who interacts with what you’ve been doing to grasp that it’s years of development, work, process, and potentially pain that’s led up to even that one piece.

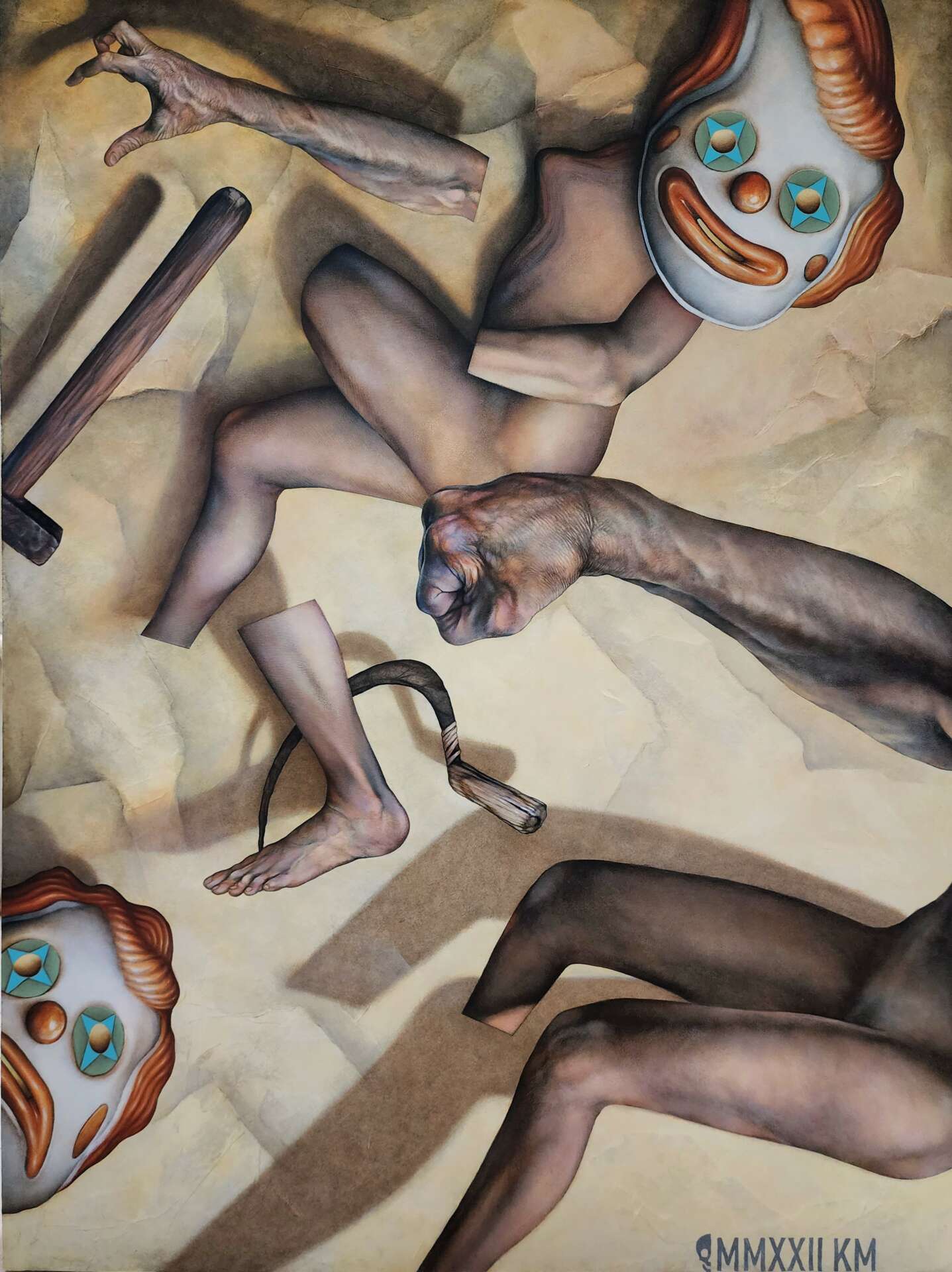

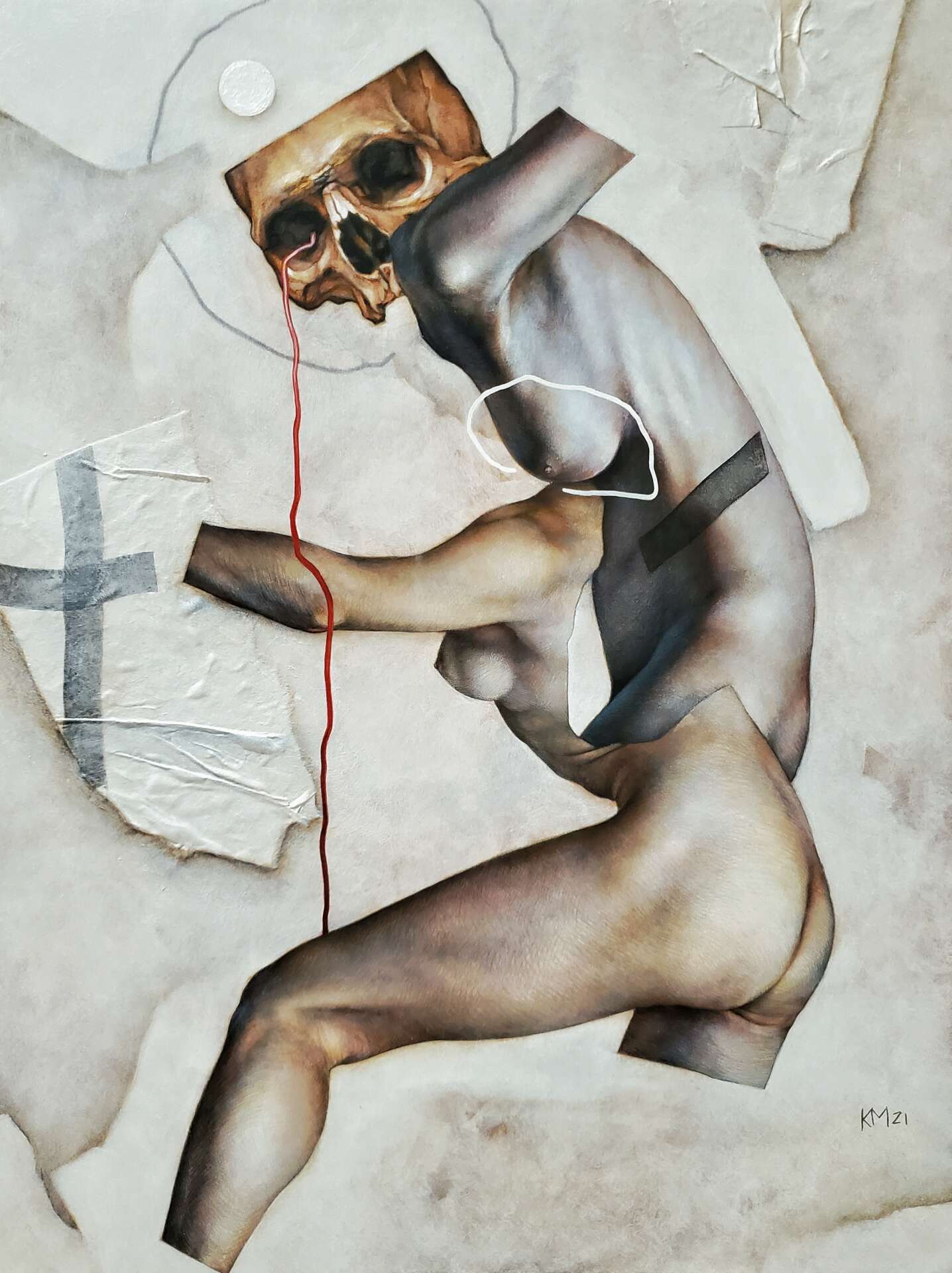

So in many ways, this is a common experience for me. I paint pictures, and people see what they see, and I learned a long time ago that being literal in what I’m trying to say is far too ham-fisted and risks being a one-liner and a boring painting. So if anything I suppose that I’ve learned to accept those interpretations as the prerogatives of the people who look at my art: if they care enough to come to any conclusions at all with what they’re looking at, then they’re taking in things that I’ve worked very hard to develop, and that, in and of itself, makes me happy. But there are exceptions, sure. And if anyone wants to know exactly what I had in mind when I painted any one particular painting, I’m happy to tell them. It’s usually not too complicated.

Awesome – so before we get into the rest of our questions, can you briefly introduce yourself to our readers.

I’m an artist, a painter, specifically. I’ve been doing art since I was little, I naturally gravitated toward pencils and pens, making marks on whatever I could, so it was pretty clear from an early age that I’d be doing something with my hands, creatively speaking. I didn’t go to any school, I’m self-taught. I don’t know if that matters, at the end of the day, one way or the other, but for me it’s made sense. I’m a punk rock kid. I had problems in my adolescence that carried on into early adulthood, mentally and emotionally, that really shattered a lot of earlier plans that might have led me down a more academic pathway than I’ve taken. So early on, at least when I began to take my work seriously, I was really wound up with resentment towards any kind of thing that felt like the status quo, which included schools and just about anyone out there with solid career advice. So, basically I did things the hardest way possible. I worked, incessantly, drawing in my car while on breaks at whatever job I was working at the time, outside factories or between pizza deliveries. I stayed up way too late every night, painting. One thing I’ll stand by, and that’s that work is everything, it’s the great equalizer. If you go to school, you’ll have plenty of teachers who’ll force you to work, at least on some level. But if you commence with being lazy after you’ve gotten that diploma, well, that art-making will have become just another thing in your past. So my way was the punk rock way, which, to continue as metaphor, means that you can have your own band, even if you’re never rich or famous (and I’ve had several bands). You just have to grit your teeth and do it. It hasn’t always been easy, but it’s been rewarding, and I’ve learned to do things outside of any standardized method or tradition, and I think with art, that can actually be essential. So I make paintings, and hopefully they don’t look like what anybody else is doing. I think I’m doing alright.

In your view, what can society to do to best support artists, creatives and a thriving creative ecosystem?

This is something that I think about a lot. If you’re interested in supporting artists, then get interested in art. It’s as simple as that. But taking it further, learn about what goes into art, the process, the lifetime of work and years of dedication that goes into developing that skill. If you’re considering buying art but you can’t afford an artist’s original work, consider a print or something the artist sells that’s in your price range. Trust me, it helps. And remember that if it’s between a $100 print from a working artist who’s taken the plunge, and a $100 original from your friend who’s working a career job and doing art as a hobby, it’s the working artist who actually needs your support! That’s probably going to come off as contentious to a lot of people, but it’s a simple truth, and it’s something that no one who’s never worked as a full-time artist will ever understand. Working artists, like anyone else in a profession or trade, want their work to be taken seriously! It’s also related to the all-too-common devaluing of art as actual, viable work. If your friend is serious about pursuing their career in art beyond just a hobby, then by all means, support them! But if you’re learning about art and you’re taking it seriously, you’ll be able to tell the difference. And if you still can’t tell, remember: art is work. If an artist isn’t working, you aren’t obliged to take them seriously, and they don’t deserve your money. After that, just enjoy the art that you like. Show up to art shows. It’s free, and you’ll often even get free wine, even snacks. You’d be an idiot if you didn’t, especially in this economy. Did I mention that your date will be impressed by how cultured you are?

Also, and this is probably another contentious statement, but along with learning about art, don’t be afraid to be critical of it. You don’t have to like everything that’s out there. You should be polite, and I’m not saying that you should approach artists and gallerists and tell them how much their show sucked. You definitely shouldn’t do that. But in order for the arts to thrive, people need to have opinions about what is good and what is not, and that’s the best way for the best art to develop and to thrive. If you compare visual art to nearly any other industry, that’s exactly what’s missing, and without a robust public offering encouragement for the art that really sings, the circles of art become incestuous communities unto themselves, out of touch with the world, the people, and the zeitgeist. Artists need you to show up, because they’re weirdos who’ve often forgotten what the rest of the world really needs from them.

Are there any books, videos or other content that you feel have meaningfully impacted your thinking?

I’m an old devourer of books. I read mostly history, lots of it, especially histories that help me weave ever more elaborate understandings of my forebears. And it’s affected my philosophy in some – to me, at least – profound ways. I mean, there’s only two generations separating myself from ancestors who were born in tiny little homes with thatch roofs and dirt floors. In the politics of the current era we often forget why our ancestors thought the way they did, and fought for what they did. When my great-grandfather was born on the side of a mountain in rural northwest Ireland, he didn’t have any hope of being an artist. It wouldn’t have even occurred to him. Joining some silly punk band and touring all over the United States would’ve seemed like some insane act of decadence (and maybe witchcraft). The vast majority of historical paintings in art museums were made by select individuals from an elite and narrow class – peasants didn’t even see paintings unless they were maybe in a church, and the possibility of making their own would have been unfathomable. Folk art, when and where it existed, held no monetary value whatsoever.

Point is, if you’re even thinking about making art, even if just for fun, you’re lucky. It’s a privilege and none of us should take it for granted. So whenever I’m feeling frustrated or down or at odds with the world, I remind myself that I’m living in a very narrow window of time, in that I’m able to do what I do. It makes me feel stronger, durable, and persistent. It’s fuel for the heart and the soul. And I hope that by doing so, I’m honoring the past and my ancestors by doing it right.

Contact Info:

- Website: www.keelanmcmorrow.com

- Instagram: @keelanmcmorrow