Alright – so today we’ve got the honor of introducing you to Kannetha Brown. We think you’ll enjoy our conversation, we’ve shared it below.

Kannetha, thanks for taking the time to share your stories with us today Can you talk to us about a project that’s meant a lot to you?

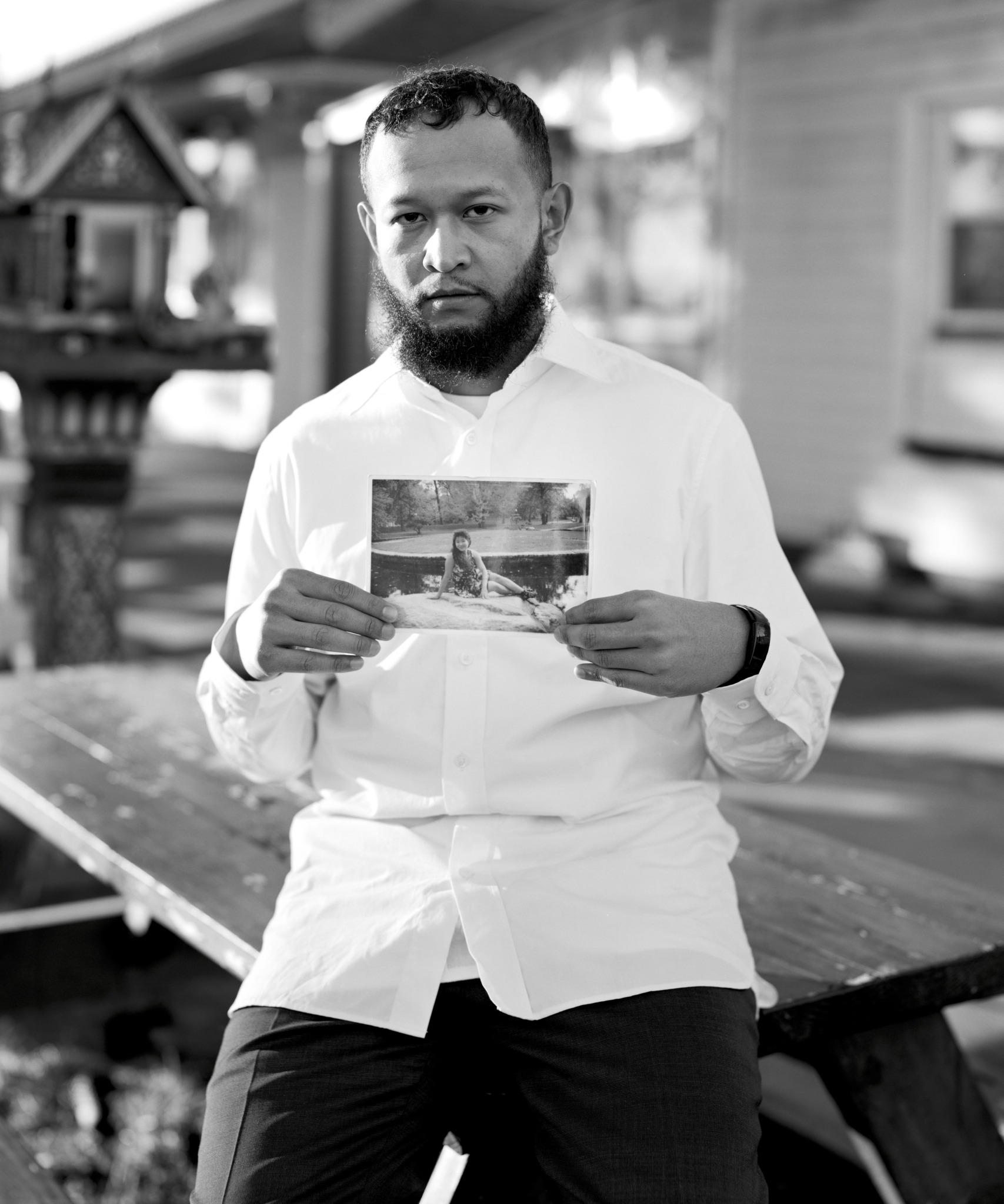

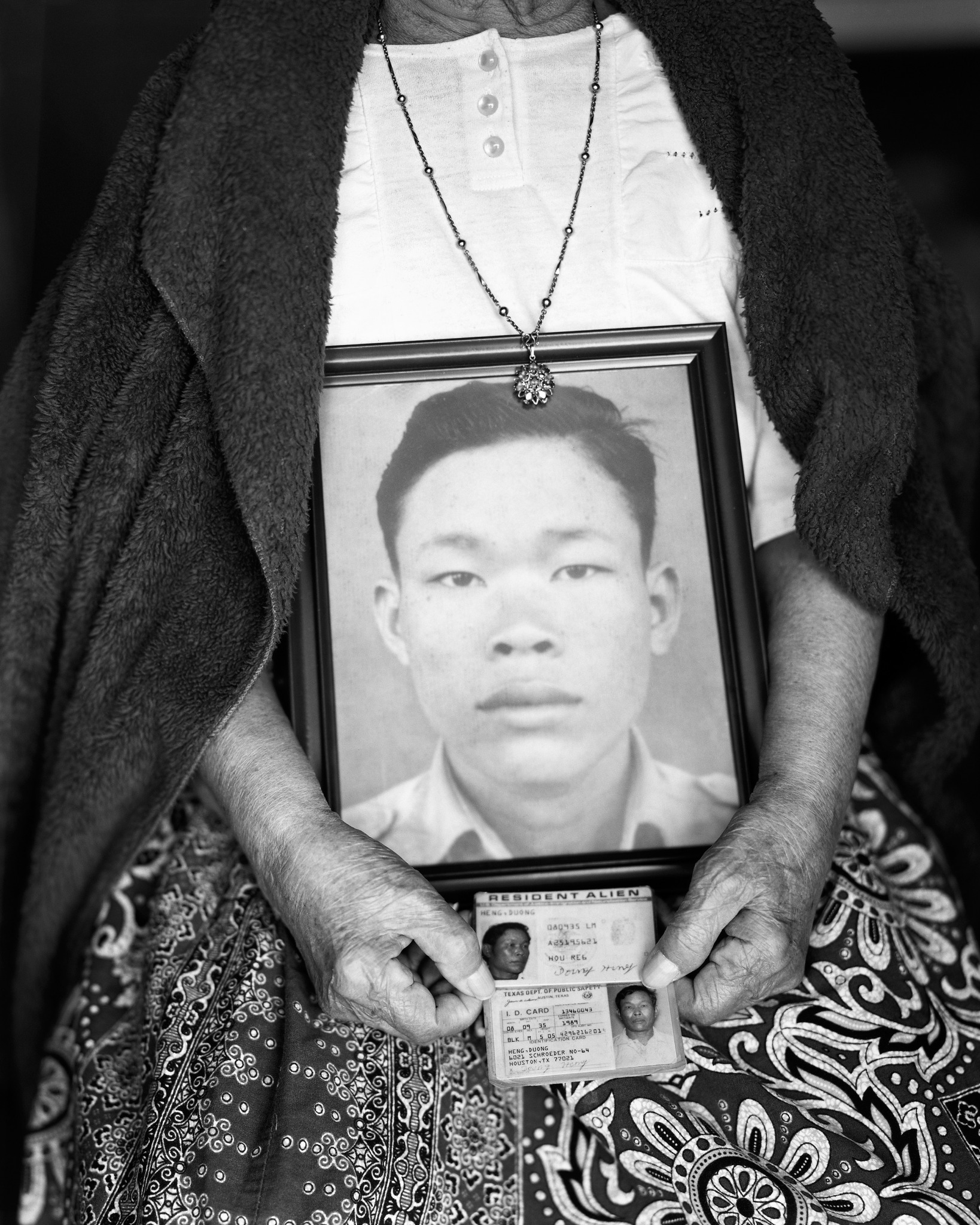

What’s incredibly important and powerful about photography is that it, alongside film/video, is the most representational art form. We are able to quite literally “see ourselves” as humans, unlike most other mediums. This power can be used for both bad and good, as photography can be used for representing what is real and what isn’t, and what is wrong and what is right. In 2017, Vice published film photographs of Khmer Rouge prisoners at the Tuol Sleng prison in Cambodia colorized and manipulated by Matt Loughrey, who edited the victims to have makeup and smiling faces when in reality, they were being documented prior to their execution. The Khmer Rouge are a communist group that came to power after the Cambodian Civil War, they were documenting their victims inside their prisons and concentration camps, and took over the Cambodian photography canon with their exploitative imagery. Both the Khmer Rouge’s documentary film photographs and Loughrey’s manipulation of them, really impacted me as a Cambodian artist. I didn’t like how these images seemed to define my community’s photographic history, and for many Cambodians, these are the only images we have of our family members, if any at all.

I started to create my own documentary projects to not only re-contextualize the history of photography in the Cambodian community, but also to create my own archive. My projects utilize film photography, just as the Khmer Rouge did in their camps and prisons, to reclaim the medium and re-contextualize it as well. Even in the language I use to describe these projects, I try to avoid photographic vocabulary that is derived from colonial language. The words like ‘shoot, capture, subject,’ etc. are represented clearly in the Khmer Rouge photographs, but not mine. Replacing these words and processes with ‘making, creating, sitter,’ etc. helps add to the goals of my own practice.

My recent projects in which I have been photographing the Cambodian community in Rhode Island, including my friends and family, as well as photographing my grandmother in New York, have been integral ways for me to bring meaning to my artwork and interpret the future of my medium and history.

Kannetha, before we move on to more of these sorts of questions, can you take some time to bring our readers up to speed on you and what you do?

In terms of my photo practice, in addition to making photography projects as an artist, I occasionally take on commissioned work across the editorial and commercial industries as well. I’ve made work for the New York Times and Rolling Stone magazine, which I am usually hired for topics or aesthetics that directly match my personal photography projects. Usually a lot of social justice work, or projects that they want on film. My clients in these industries often hire me to bring an artistic sensibility to editorial or commercial photography, to tell a story and draw in a younger audience. I got into this industry via personal connections through word of mouth or social media, some being directly affiliated with my alma matter: MassArt in Boston.

For my day job, I currently work as an image specialist at IOLabs in East Providence, Rhode Island, where I work in printing, scanning and editing to put it simply!

What’s a lesson you had to unlearn and what’s the backstory?

A lesson I had to unlearn in my career, so far, was funnily enough through a Drake song (which is kind of embarrassing, but it is what it is). “Don’t ever take advice, that was great advice.” In my early career, especially being a woman, and at the time being so young, I often found myself asking for a lot of advice or subjecting to myself to unwanted advice and critique. I learned with time, that the majority of the information I learned during these conversations actually didn’t benefit me at all, and that I should’ve taken them with a grain of salt. I’m not saying to cancel out all advice people give you, but rather understand that they are coming from their own perspective, not your own. You have to be careful with whom you share your precious work with. Keep your artist circle small and sweet. Remember who your audience is when you do look for help or critique. Who are you really making work for, and how does their opinion matter most to you? Stubborn, maybe. But this mindset has now protected me from past moments where I would lose myself in the ideas and preferences of other people, rather than myself and my audience. Whether it be I stopped making, or stopped making my own way, I realized afterwards that my work is special because it’s me. Going to a fine art school, I had to find my own rhythm in what is appealing to that industry, and to my own community– which isn’t exposed to museum world and art world in general. In my writing and photographing, I remembered to keep my descriptions true to me, and easy to understand. Less is more.

How about pivoting – can you share the story of a time you’ve had to pivot?

I tend to be pivoting on a monthly basis in terms of my career and interests, but it all makes sense in the end. My biggest pivot was during senior year of high school, when I wanted to be an elementary school teacher and ended up taking a year off to create a photography portfolio and pursue photo school. In the end, it all made sense for me, but I have found myself yearning to be back in the teaching environment I crave. However, I do find that from occasionally teaching classes. I do one day want to explore this as a career, but we’ll get there.

Contact Info:

- Website: https://www.kannethabrown.com

- Instagram: @kannetha.brown

Image Credits

Photos by Kannetha Brown