We were lucky to catch up with Junli Song recently and have shared our conversation below.

Junli, thanks for joining us, excited to have you contributing your stories and insights. We’d love to hear the backstory behind a risk you’ve taken – whether big or small, walk us through what it was like and how it ultimately turned out.

In many ways, becoming an artist is the greatest risk I’ve taken in life. Growing up, I never saw this as a feasible career choice. I was raised by immigrant parents who moved here hoping for a better life, and so something as unpractical as art was simply not an option. I grew up unthinkingly checking off the list of Chinese American stereotypes: straight-A student, good at math, took all the AP courses, played classical piano, always obedient, attended prestigious universities (and more importantly, studied respectable, employable disciplines). My wonderful parents still supported my love for painting and drawing, purchasing any and all materials I needed and my dad even built me a beautiful wooden easel. However, at the end of the day art was something to do in our free time, not a profession. Add on to this the fact that I was not aware of any contemporary Asian artists at the time. The only example of Asian artistry I saw was in classical music, when I attended the Chicago Symphony Orchestra with my parents. Yet as much as I admire these musicians, their example did not convince me to pursue an artistic career.

I only understood the reason why after listening to an interview with the poet, Ocean Vuong. He has written and spoken extensively regarding the condition of the Asian-American artist. Specifically, he points to the way Asian American creativity usually exists in service of other, often Western, art (the obvious example being classical musicians playing Bach and Beethoven). Vuong poses the question: what happens when Asian American artistry stops acting as merely a conduit, but rather takes on a life of its own? It took time for me to realize that I wanted to create something that was completely my own, and that only art could fulfill this need. I literally had to escape to Italy before I dared to tell my mom (via email because I was too scared to say it out loud) that I was about to trade in my carefully prepared life and career for a wild card. It has been six years since then, but some days I am still amazed to realize that I am somehow, improbably here.

Awesome – so before we get into the rest of our questions, can you briefly introduce yourself to our readers.

I have not followed a conventional path to becoming an artist. In hindsight however, I actually would point to my background in the social sciences as the starting point of my journey. During the summer of 2015, I conducted anthropological fieldwork in the Black townships of Cape Town, South Africa for my thesis at the University of Oxford. During conversations, I was taken aback by how often people thanked me for listening. This gratitude was born from social injustice because not everyone has the privilege of being heard. As I wrote my dissertation, I kept returning to the question of whose stories are told, and why? The answer was obvious: those who are in power and uphold what Bell Hooks labeled the ‘white supremacist capitalist patriarchy.’ The more important question then became whether I could do anything to change this.

At the outset, I reached for the obvious answer. Stories meant books, and because I had always loved art, I decided to pursue book illustration. However, I quickly felt stifled by the limitations of commercial work. It also took these years for me to conceive of the idea that my own stories might be worth telling. In hindsight, this was a symptom of what Summer Kim Lee calls the ‘after you’ embodiment of Asian Americans, which she defines as our predisposition to accommodate others, the expectation placed upon us to always be in response to someone else. For me, a large part of my evolution as an artist has been deciding to stop accepting this position in the ‘after’ and to center myself and my community in the narrative.

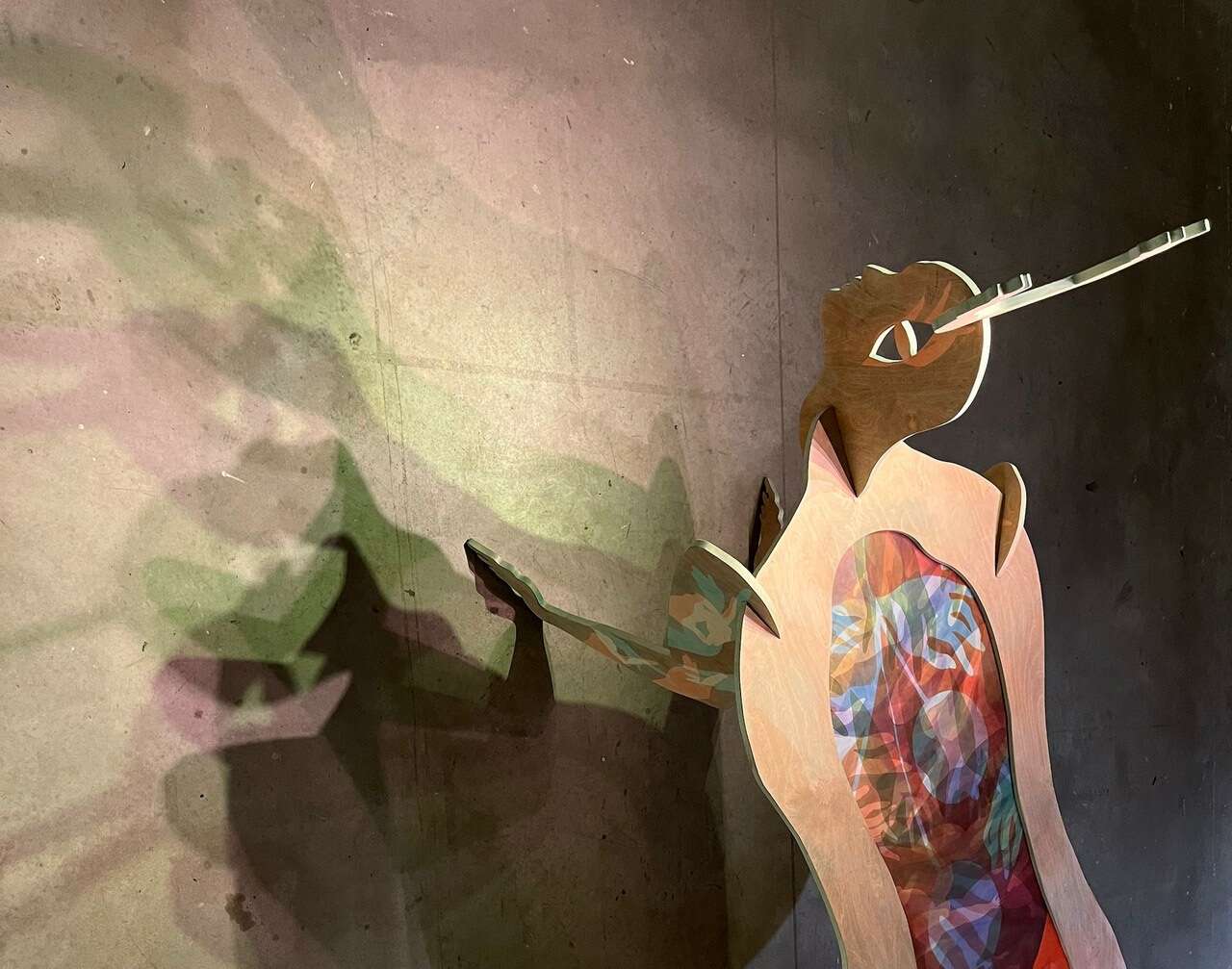

My practice revolves around world-building, and I create across various media including printmaking and installation, to explore personal mythologies informed by a feminist diasporic perspective. These narratives center around a female re-imagining of a Chinese deity, whom I have named Nu Xingtian. The world created within my work exists as an imaginary realm where the liminal becomes a space of alternative existence. I have undertaken the project of world-building to create a space where I belong and to make sense of the complex, often contradictory, realities of existing between cultures. As an artist, I do not make work ‘about’ my identity as a Chinese-American woman. I am wary of the idea of art as representation because I have no desire to present my selfhood for consumption. At the same time, my identity is inescapable: while my work is not ‘about’ my experiences moving through this world, those experiences are the conditions which make my work possible.

Since completing my MFA in May of 2023, I have been focused on continuing to experiment in the studio and grow as an educator. I am currently the Grant Wood fellow in printmaking at the University of Iowa, which provides a wonderful opportunity to focus on my studio research as well as teach one course a semester. My work has been moving in the direction of increasingly immersive installations, and as I build my creative universe I am equally building the physical spaces where I install.

For you, what’s the most rewarding aspect of being a creative?

I think the wonderful thing about being an artist is having the opportunity to process and transform my own lived experiences. It is an ongoing journey of self-discovery, and I continually find myself surprised by the process. For me, the most rewarding moments take place when I question my own assumptions, and the ways I see the world. To give a concrete example, I was recently reflecting upon my thesis exhibition last February. Research and writing is a large part of my practice, and I am particularly invested in thinking about the ways we see the world, both physically and conceptually, Lately, I have been thinking a lot about multiplicity and obscurity after reading Jun’Ichiro Tanizaki’s In Praise of Shadows and revisiting Byung-Chul Han’s Shanzhai. These themes also link back to one of the foundational texts for my art practice, Edouard Glissant’s The Poetics of Relation, particularly his concept of opacity. In my thesis installation, I created a sculpture with a blue-green hue, which I intended as a reference to the Chinese colour term, qing. What drew me to qing was its transformational qualities: the exact colour it takes represents will shift depending on context. Taken on its own, it is blue-green, but it can also be blue, green, black, grey, even purple. I was drawn to this colour as a visual metaphor for multiplicity and transformation. However, in looking back on this choice, I realized that I missed a crucial opportunity: I had diminished this incredibly complex colour term into just a single colour. I read an article about how the use of qing has changed in the Chinese language because of the widespread anglicization of the world. Because Western perspective prioritizes clarity and distinct boundaries, a colour like qing does not fit within this logic. And while the word itself is still widely used, it is no longer in use as a basic colour term as it historically was. Yet I performed the same reductivity upon it as the West has by forcing qing into a single colour. And so I realized that I also had to unlearn this way of thinking within myself. Little moments like these make me realize how becoming an artist continues to make me aware of my own limitations and preconceptions.

What can society do to ensure an environment that’s helpful to artists and creatives?

I think a basic frustration every artist has encountered is not having our work taken seriously. I think society confuses passion with fun – because while there are fun moments in creativity, it is an incredible amount of labour. As someone who did not begin in the arts (I originally studied economics and development studies), I can say that becoming an artist has been the most exhausting change in my life, even though it is also the most rewarding. The physical hours spent as well as the emotional energy is perhaps not something easily understood by non-creatives, but I hope as more of us speak and share about it, there will be a greater level of awareness around this subject. I do feel incredibly fortunate to pursue what I love as a career, but there are some downsides to never being able to step away from your job. Being an artist is more than a vocation, it is a lifestyle.

Contact Info:

- Website: www.artsofsong.com

- Instagram: @artsofsong

Image Credits

Headshot – Andrew Kilgore Images 2 and 3 in my work – Sky Maggiore