We caught up with the brilliant and insightful Joseph Summer a few weeks ago and have shared our conversation below.

Joseph, appreciate you joining us today. Can you open up about a risk you’ve taken – what it was like taking that risk, why you took the risk and how it turned out?

Graduating from Oberlin College at the age of 20, in 1976, with a degree in composition, I was unexpectedly solicited by Robert Page, the dean of music at Carnegie Mellon University, to accept a position at the school. The university’s director of music theory had gone AWOL just weeks before the fall semester, and CMU was in desperate need of a music theory professor to design the Music Theory 101 curriculum and teach classes. Not a teaching assistant gig, but an actual position at CMU, I had suddenly been propelled into the position that graduates of music conservatories strive to attain through years of arduous struggle. (The reason CMU had called me isn’t obscure. I’d matriculated at Oberlin at the age of 16, was a music theory prodigy, and had been assisting the music theory and acoustics professors at Oberlin since my Sophomore year. A former music instructor of mine who was at CMU in another discipline had been asked to fill in for music theory but had demurred, and recommended that Dean Page give me a call.) Even though I was quite the phenomenal young music theory student, finding my way into academia as a teacher at the age of 20 was a signal accomplishment and appeared to herald the beginning of a successful career in academia. After a year of teaching undergraduate music students who were my age and older, with ease; and the approval and admiration of my colleagues, friends, and family; I realized that though I’d developed the requisite skills to be a music theory professor and had entered the field through the felicitous circumstance of a music theory professor on the lam, I didn’t want to be a full time music theory teacher and a part time composer. The prodigious skills I’d developed in music theory I’d intended to serve me as a composer, not as a teacher. Less than two years after beginning what promised to be a comfortable life teaching music theory and pursuing composition in the fashion of my own prior composition teachers at Oberlin, I resigned from academia, over the pleas and objections of my fellow professors, friends, and family. I didn’t take this step unaware of the risk. I can’t say I embraced the risk with joy. I was terrified of my own decision since it meant choosing a path wherein success was questionable regardless of my confidence in my skills as a composer. I took a leap of faith not out of belief in the inevitability of triumph, but out of the apprehension that having a comfortable career was not my real objective. Failure was probable, but the alternative – a congenial life as a professor – was not worth not taking the risk.

Awesome – so before we get into the rest of our questions, can you briefly introduce yourself to our readers.

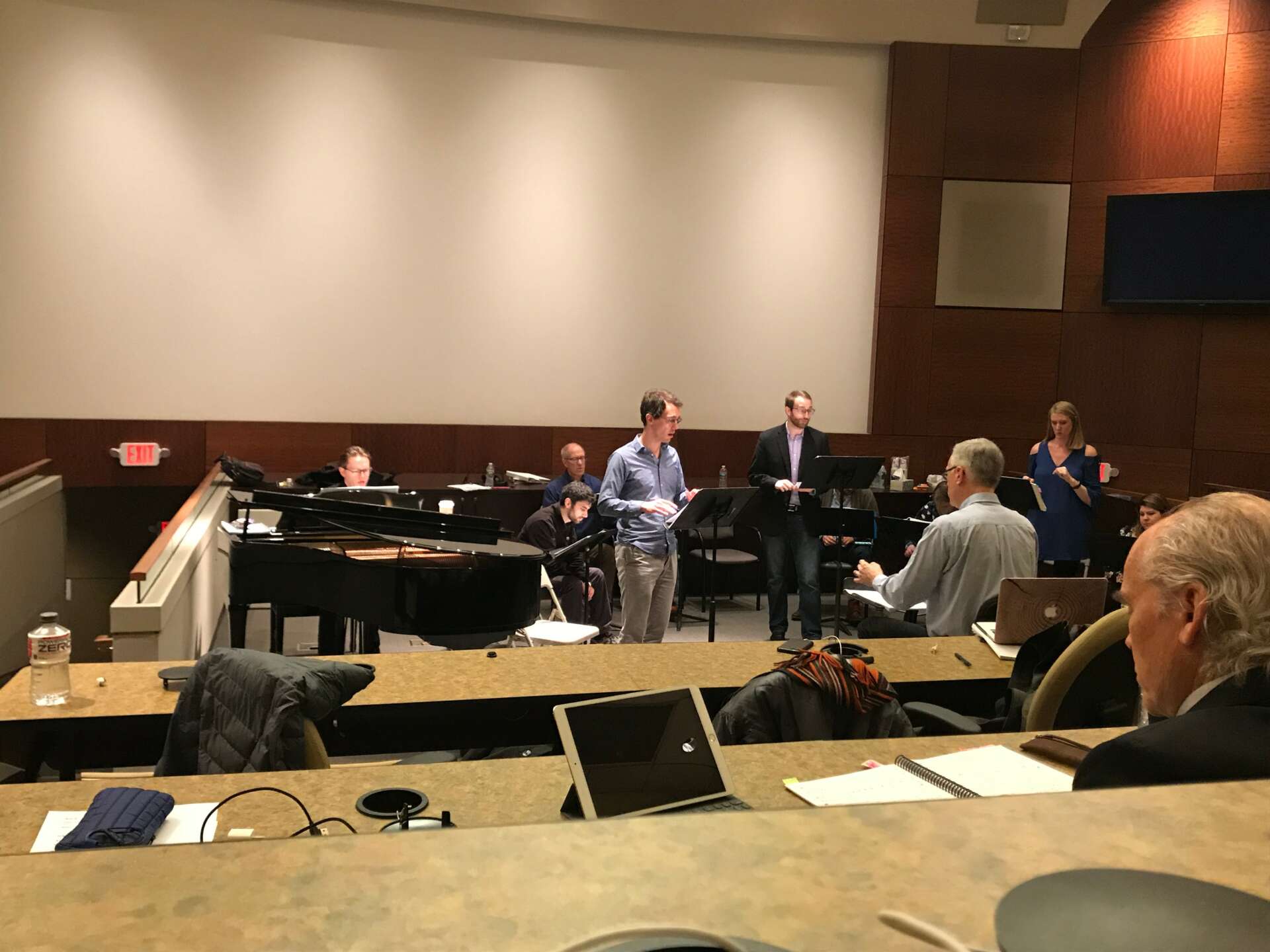

Leaving academia behind, I realized I’d need to be able to create products – musical works – without the support of the typical resources available to a college professor. I sought out an expert in the field of the performing arts, an expert in the process not in the art itself, in order to learn how to build and sustain the platform upon which the art is presented. Yolanda Marino, the executive director of the Duquesne Tamburitzans, agreed to allow me to shadow her for two months as she ran her organization. I saw how she performed the tasks necessary to produce the art, from personnel to money management, and everything in between. I accompanied her even into fund-raising meetings, sitting quietly as she coerced bank vice presidents and corporate chiefs to contribute to the Tamburitzans. After I’d digested the information I’d learned from Yolanda Marino in 1978, I began planning the construction of a vehicle for my music. In 1980 I commenced the establishment of a corporation, the Contemporary Opera Company of America (COCOA), to serve as the medium for presentation of my music. I consulted with a young attorney, Jeffrey Hutchins, who guided me through the process of creating a legal entity, and subsequently participated in the formation of that entity that would serve my music to this day (though under a new name and with considerable evolution.) Our first production was my chamber opera, The Tenor’s Suite, which was produced in Philadelphia in 1981. COCOA eventually transmogrified into The Foundation for Modern Opera and eventually The Shakespeare Concerts, its present DBA label. As Executive Director of The Shakespeare Concerts for the last twenty years I’ve produced scores and scores of concerts and recordings. Though my singular goal is the promotion and performance of my music, I’ve produced the works of other composers living and dead, a beneficial side effect of my less than altruistic motivation.

In your view, what can society to do to best support artists, creatives and a thriving creative ecosystem?

I don’t think society can do anything to support artists. As an artist I want to shock and awe society; and I want to affect my collaborators (the singers and instrumentalists with whom I work) in the same way. Approbation and applause are not responses I am looking to achieve. I’m happiest when I can shake a percipient’s soul. Recently I presented concerts in which I had the vocalists emerge from the audience during the preliminary tuning of the on-stage orchestra instruments and begin a loud protest against the classical music concert I was producing. The audience members were – to my delight – stunned and confused. After the soprano had loudly proclaimed that classical music “is elitist,” she and the other “protesters” were interrupted by the arrival of a baritone, on stage, who admonished them, in song, an aria I’d written based on Shakespeare’s Coriolanus. The piece, “The People Are the City” is a rhetorical oratorio that addresses the cognitively dissonant union of liberal philosophy abiding in the realm of the most privileged and elite amongst us. I allowed the audience to relax for a while, as the protesters quickly joined the baritone on-stage and performed the kind of classical music they were previously condemning. I wanted the people, the city, society, to enjoy my music but also to be confronted by it. I don’t write music for society. I write music as a confrontational argument against society. The “thriving creative ecosystem” in my world is the opposition that I joyfully strive against. Why would society want to support an artist when one of the principal responsibilities of the artist is to force society to question its own comfortable assumptions?

Is there a particular goal or mission driving your creative journey?

I’m communicating with dead and unborn composers, writing letters in the form of music to my precursors and – if I have done my job – to those who will succeed me. Listening to master composers’ solutions to musical problems, I am inspired to contemplate other solutions and other problems. My musical offerings are an attempt to converse with composers whom I’ll never meet. The unintended consequences of the work, of the conversation between myself and deceased and yet-to-be-born composers is music that pleases audiences, displeases audiences, engages audiences. I’m ecstatic that listeners enjoy the music I write and produce, but I’m really not ever focused on the concept of pleasing the audience. It’s the thrill of the hunt. The musical problems are the prey, and I must capture and subdue them. The musical score is my list of instructions on how to succeed in the pursuit. People who attend the concerts or listen to my music reap the benefits of feasting on the spoils of the hunt; but I’d have conducted myself the same way even were there to be no guests at the table.

Contact Info:

- Website: https://www.josephsummermusic.com/

- Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/TheShakespeareConcerts

- Youtube: https://www.youtube.com/@watchhourfilms

- Other: https://shakespeareconcerts.org/