We were lucky to catch up with Jon McCaine recently and have shared our conversation below.

Jon, thanks for taking the time to share your stories with us today Was there a defining moment in your professional career? A moment that changed the trajectory of your career?

As part of my pre-doctoral internship training, I did on-call rotations in the emergency room of a medical center. A woman who had just been physically assaulted by her boyfriend entered holding a young child by the hand who looked scared and confused. She was frightened and needed a place to stay. After searching and searching, I was able to find an emergency shelter and arranged for be transported and given a space. for her and her daughter. She hugged me and thanked me on leaving. I felt satisfied that things worked out.

On completing the internship, I accepted a post-doctoral position as clinical director of a small rural clinic that then hired me a year later as an Independent, , licenced professional to run the clinic. It was staffed with just me and student interns from the university. About three years later, I was supervising a young Jewish intern who was doing home visits, which was not unusual in a rural area with limited transportation options. In supervision, she reported that her client, a single woman with an elementary school-aged daughter, was talking with her in the living room when the daughter came running into the house laughing with young African American boy who was a friend. The woman paused as she was reflecting on her past circumstances and said that friendship would never have happened in the past because her ex was a white supremacist, and they would never have allowed such a thing. She said she was at a desperate point in her life when her ex had beaten her up and threatened to kill her. she went to the emergency room of the local hospital, and “this black guy” made sure she was safe and got her an escort to get to a shelter. She never went back to her ex and moved to this rural area to start her life over..

This and a couple of other unforeseen outcomes taught me never to underestimate the potential impact of our actions on those whose lives we touch. Another was working with a middle-aged woman who revealed how, as a child, she intended to step into step into traffic and kill herself on the way home from school, but a kind comment from a teacher ” I don’t know what is wrong, but I just want you to know I care about you…” distracted her and she simply forgot her plan to kill herself. When my client found out I did closing lectures each year to a class of educators completing their teaching certifications, she asked me to thank them because she never got a chance to thank the teacher who simply noticed her and saved her life. I told this story each year to the hundreds of graduating students, and there was rarely a dry eye in the auditorium each time .

Jon, before we move on to more of these sorts of questions, can you take some time to bring our readers up to speed on you and what you do?

I am a husband, father, and a brother to my two brothers and two sisters. I have always been drawn to mysteries and loved reading Encyclopedia Brown and Nancy Drew mysteries as a youth. Both of my parents were athletes in the U.S. Army and I grew up heavily involved in multiple sports with aspirations of being able to be an Olympic sprinter after 8 years of competing in Junior Olympic competitions., As a sophomore in high school after winning the league championship in the 100-yard sprint, I suffered a catastrophic knee injury running hurdles that resulted in a total change in my life perspective and goals.

I spent the next few years trying to re-imagine a life without sports competition when my family, friends, and community with good intentions, try to encourage me to continue to pursue a life that was no longer possible. I went to a college in California that was the farthest geographically away from my home town to escape benevolent but unrealistic expectations. I had no idea at the time that this “re-imagining” would be a cornerstone of my practice as a clinical psychologist or that the training in wildland firefighting, which I did to pay for my education, would become something that applied to putting out fires that comsumned people from within as well. Part of re-imagining was how the study of psychology rekindled my fascination with seeking solutions to mysteries

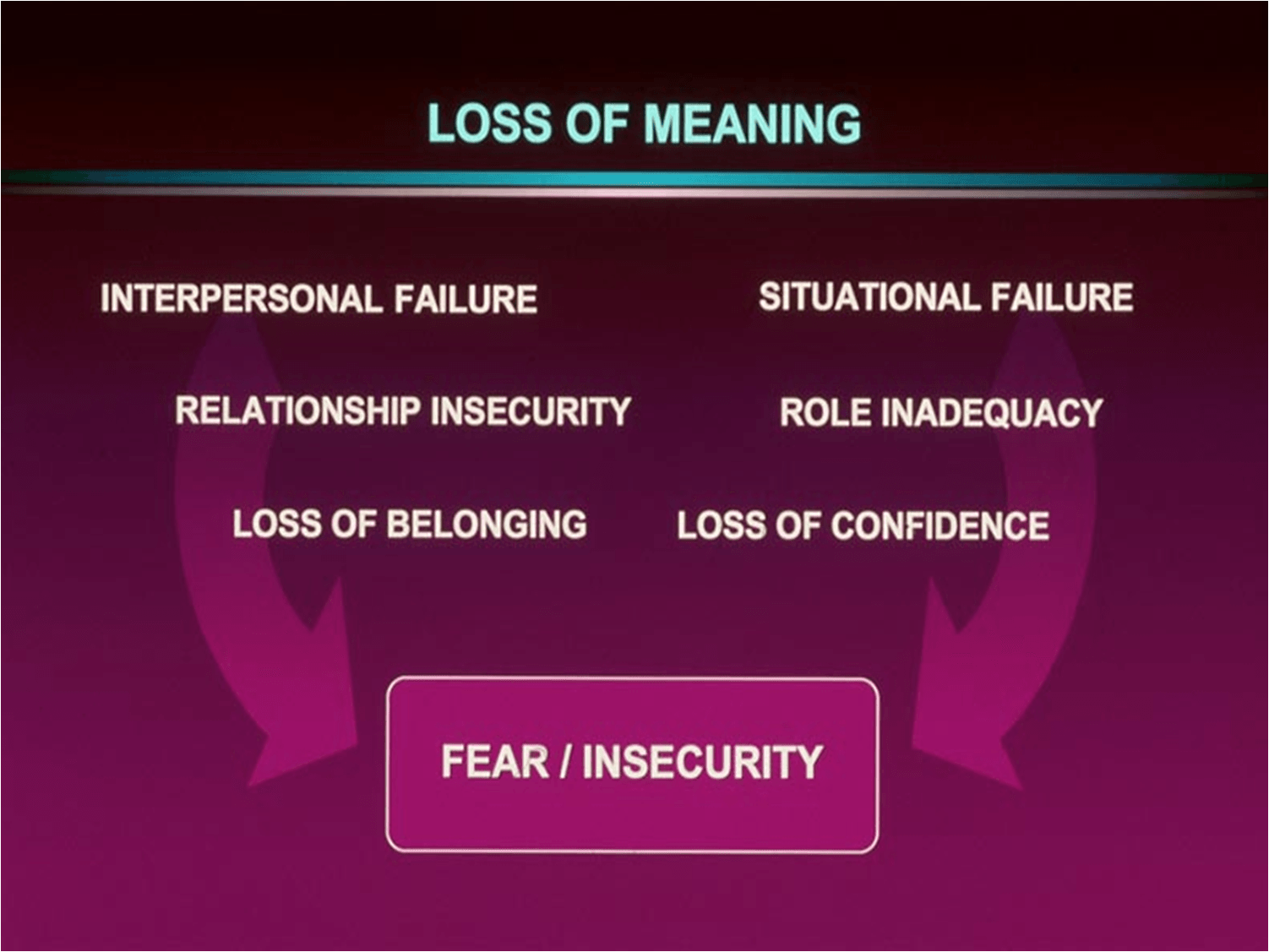

Regardless of theoretical orientation and the science of best practices in clinical work, I have learned the truth is invariably quite simple, but this does mean it is easy to overcome when we are challenged with the dilemma of contrasting priorities and alternative possibilities in the strives we invest in to carve a future path. While I understand the nature of clinical diagnostics of psychiatric disorders and the real challenges these disorders present, the true struggle seems to be an existential one with two fundamental themes. One is the fear of something or someone present in our lives that we do not believe we can live with. Two, the pain of something or someone missing from our lives that we do not believe we can live without. Sometimes, if not most times, it is a combination of both, as a teenage boy taught me because he felt he could not live with or without his abusive father.

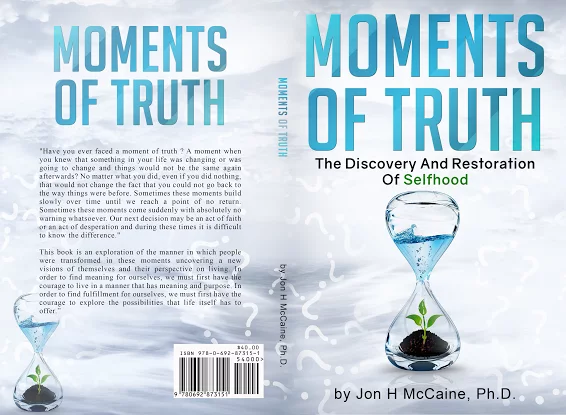

In my book, Moments of Truth: The Discovery and Restoration of Selfhood, I reflected on over 30 years of clinical practice seeking common themes in the nature of dilemmas and traumas, how they became defined by the stories about themselves as being the wound rather than being wounded in moments of fear and pain, and how they gained liberation by re-imagining the meaning of the past, the circumstances of the present, and the possibilities of a future previously unknown and unseen. This has been the essence of my practice as a therapist and of my training of aspiring interns and young practitioners seeking to find a style and approach to practice that resonates with their own unique humanity

Learning and unlearning are both critical parts of growth – can you share a story of a time when you had to unlearn a lesson?

I saw a bumper sticker that captured the essence of what I have had to unlearn. It read simply: “Don’t Believe Everything That You Think. ” Knowledge is ever evolving whether it is self-knowledge or technical knowledge in a particular field of study. In the Introduction of my book, I wrote a somewhat tongue-in-cheek but real section called “Confessions of a Recovering Psychologist” that is the basis for much of my work and training with therapists, requiring them to “re-imagine” certain myths about human nature and clinical practice that involve assumptions that I have found are not particularly helpful personally or professionally. As a profession, we are committed to the idea of “a personality” that encompasses who we are rather than “what we are most likely to do under certain conditions”. There is a difference between saying and believing, ” I can’t do that, it’s not me,” versus understanding “typically that is not something I am comfortable doing” but are fully capable of doing it. Stories of our inadequacies often began as someone else’s story about us that we then embrace as our own, but forget someone else authored the story in the first place.. This is a concept that is easier to embrace than the next one.

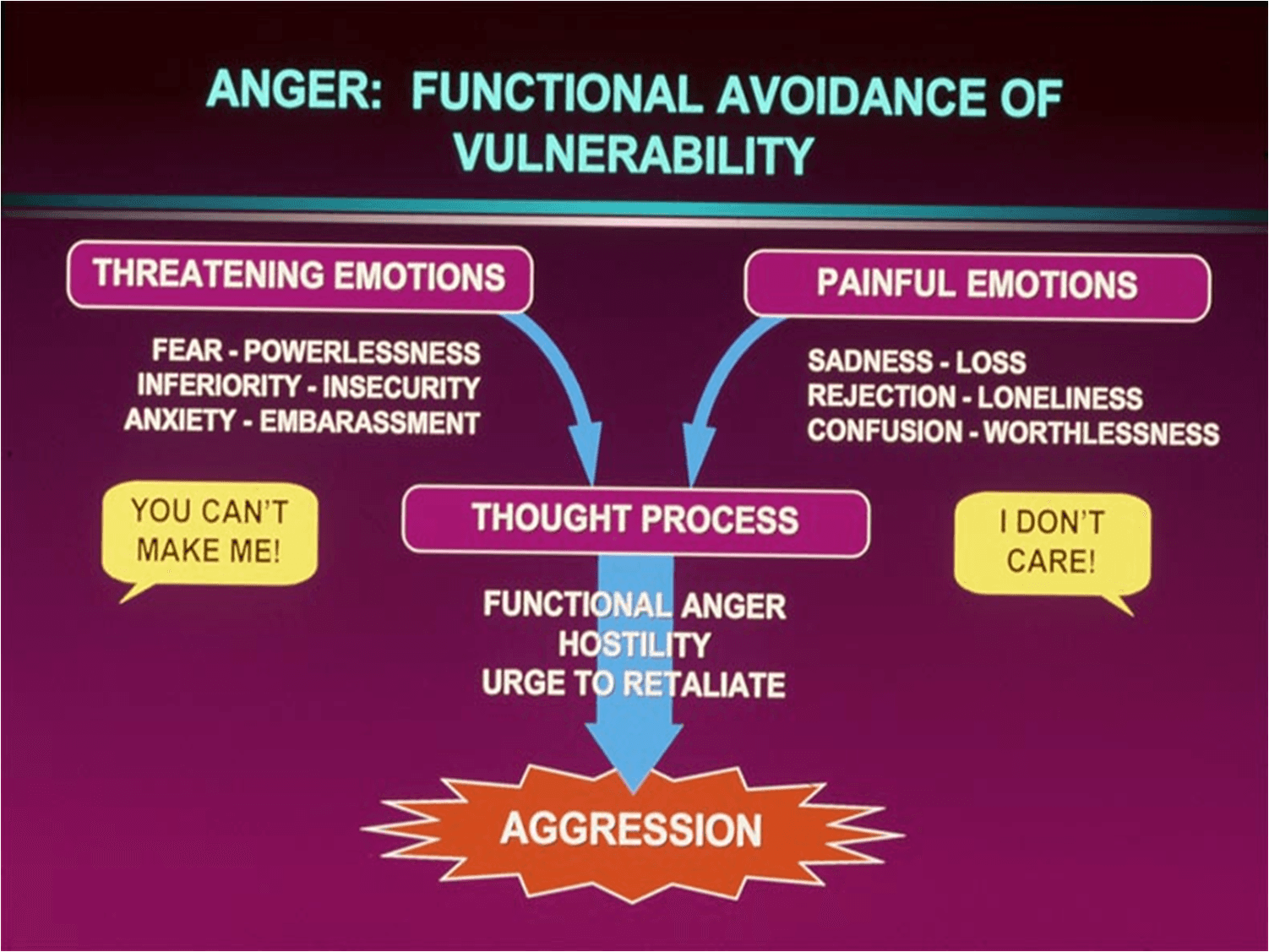

As professionals and members of the general public, we are taught that emotions are almost sacred, and the validity of emotions is not to be challenged. We are, in fact, “entitled to our emotions” as inherently true expressions of our experiences.. We are in fact, active participants in the construction of our emotional states, and because we are human and imperfect, our interpretation of events past, present, and future are also subjected to flawed interpretations. The notion of being responsible is generally associated with actions and decisions, not with our emotional states. Teaching “emotional responsibility” means examining whether our expectations are credible and the degree to which our narratives stories about ourselves, about others and about the circumstances we find ourselves in serve or compromise our best interests. By teaching people to create viable different stories that result in various emotional outcomes in any given situation, we take responsibility for our emotions and find ourselves capable of moving ourselves emotionally by re-imaging our narratives that create the emotional state. “Did your mother do this because she doesn’t care about you or because she was afraid and was trying to protect you?” Do you want to feel unimportant or loved? Did your son lie to you because he doesn’t respect you or because he cares about what you think of him and was afraid to disappoint you? What is the bigger problem, that he lied to you or that he is afraid there are conditions he has to meet for you to love him? Therapists that I have trained routinely tell me that this concept of constructing and deconstructing emotions has changed practice but more importantly have changed their lives personally.

Do you have any insights you can share related to maintaining high team morale?

Micro-managing is the best way to compromise a team’s efficiency and morale. Many supervisors/managers seem to try to mold a team to their own will and methods, which destroys initiative and personal investment in the team’s mission and goals. This initiative and personal investment are the essence of high morale. Also, the covert agenda of any team manager/supervisor is the professional growth and development of members of the team in preparing them to become the best they can be in their current positions as well as assisting in a career path beyond their current positions. It is important that each member of the team understands the value of other team members relative to the overall mission of the team and that there will be competing interests and priorities on occasion.

The team must feel like a team, not just a collection of individuals. After carefully selecting the first member of my team, she was directly involved in the interview of the next prospective hire. From that time on, after HR reviewed resumes and did preliminary interviews of credentials, each candidate was subjected to an interview by the entire team, which I observed but did not participate directly in. After the interview, the team deliberated and made the hire/no hire determination. As the high-risk youth program grew, eventually, a third step to the interview process was added.. Candidates were required to attend the monthly community meeting of the youth in the program. The youth leaders conducted the interview while my staff and I observed. After the interviews, the youth deliberated and made hire/no hire recommendations. Staff members who were hired routinely look back on the youth interviews as both the best and the most terrifying interviews they ever had. This clinical team had the highest productivity, the highest morale, and the best retention rate in the organization. After being hired, I personally took a portrait photo and mounted the photo on the wall with other staff members. When employees leave the team, sometimes at my insistence to accept promotions both within and outside the organization, their photos were taken down and signed. A “goodbye group” was held at the community meeting, which was highly emotional. The lesson is simple. When you invest in people, they will invest in you.