We recently connected with Joey Lehman Morris and have shared our conversation below.

Hi Joey Lehman, thanks for joining us today. Learning the craft is often a unique journey from every creative – we’d love to hear about your journey and if knowing what you know now, you would have done anything differently to speed up the learning process.

I know for sure that I am still learning to do what I do. I don’t believe that ones craft is something that simply summits once you have invested a certain amount of labor and time. In my circumstance, it has involved an ongoing series of experiences, investigations, actions, failures, repetitions, plans B, C and D, all the while taking notes. It is filled with crescendos and pitfalls. As I see it, the knowledge of, and relationship toward ones craft is seemingly, actually ideally, endless. I do not see much purpose in moving forward if that relationship ceases to evolve, morph, or grow.

I have never been interested in speeding up the learning process. I am not a fast learner, I am not a fast anything really, so speed is not one of my strengths or desires. Because of this, I do not have too much to offer in terms of an economic story. My learning process is geologic and parallels my interest in the physical world and is at the core of my very matter. The skills that I do think are essential involve resilience and endurance. I possess endurance, not speed. I am in no hurry, but I will keep going. Artists who cherish what they are a part of need to keep on going in some manner. Our culture should be more willing to value and foster these attributes. Art is not simply an activity one engages with for several years while passing through educational institutions which must then be abandoned by necessity in favor of entry into the marketplace. It is a significant part of being human and being connected with other humans. And yet obstacles like insurmountable student debt, a serious lack of healthcare, cost of living, and unemployment levels in the field throw this part of ones humanity into disorder.

Great, appreciate you sharing that with us. Before we ask you to share more of your insights, can you take a moment to introduce yourself and how you got to where you are today to our readers.

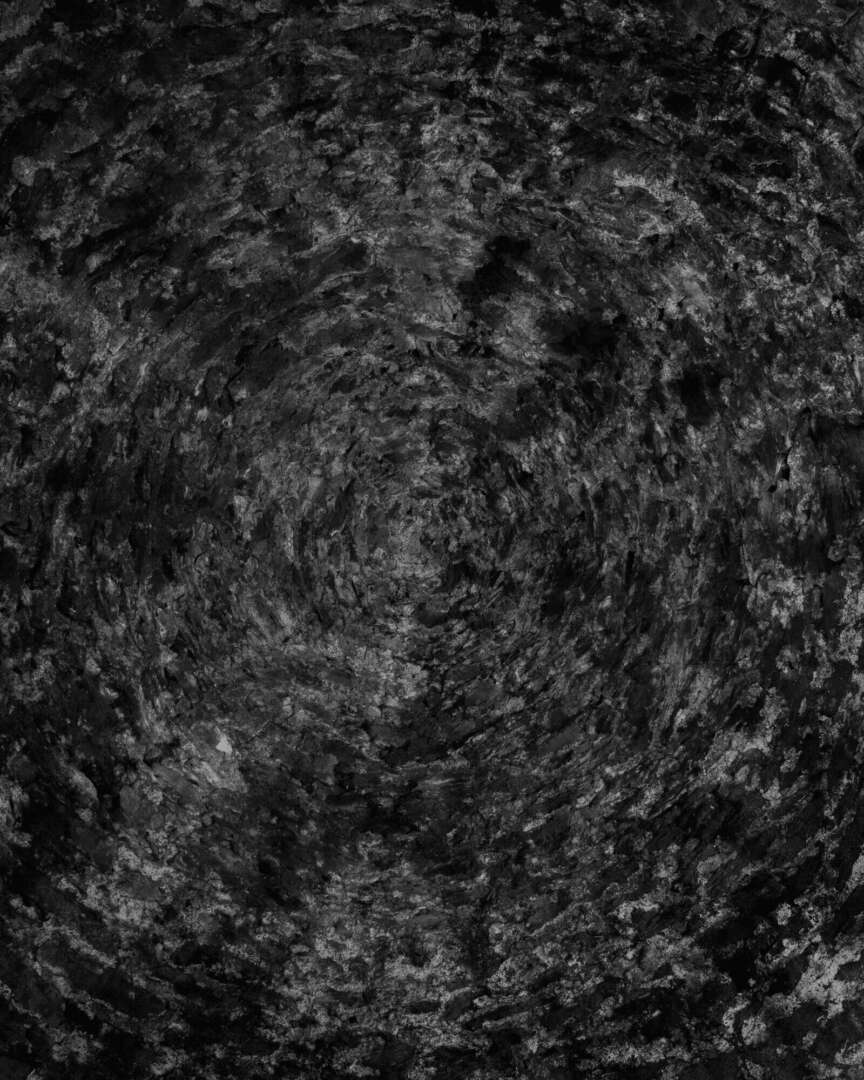

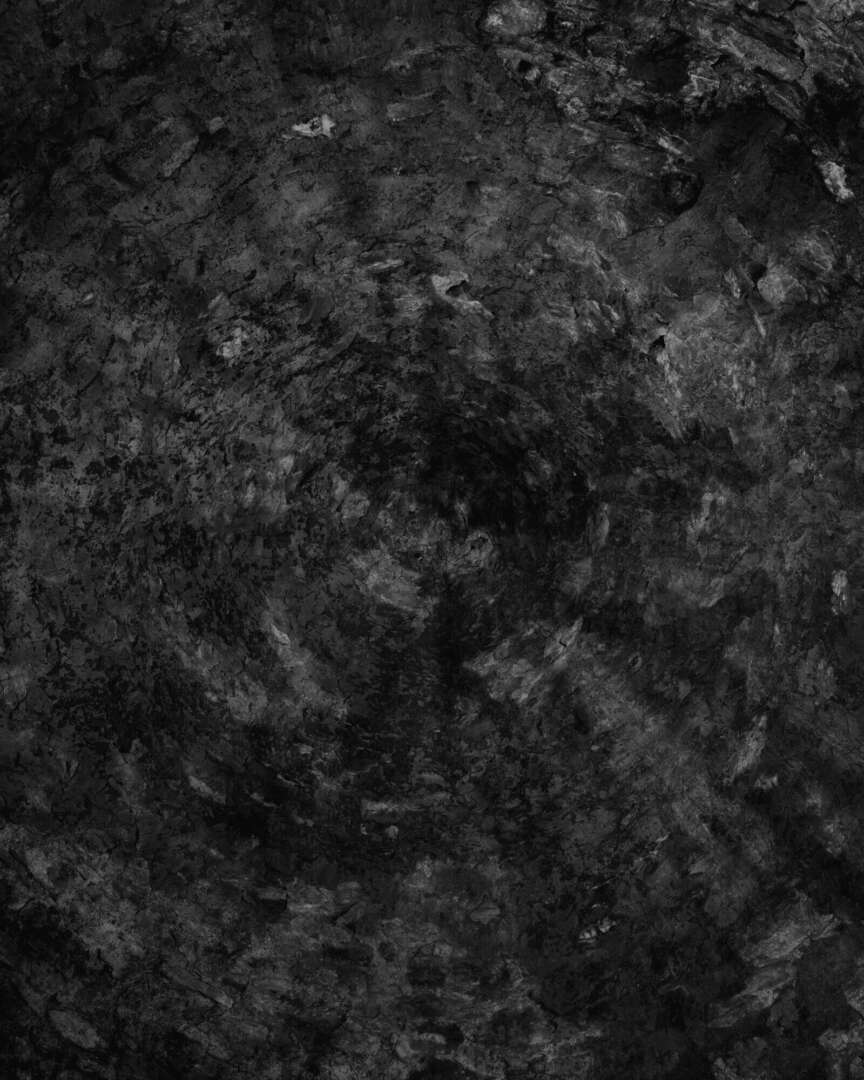

I was born and raised in the Los Angeles area, where I still reside, love, and work. I am an arts educator and a maker. I primarily make large-format photographs that hang on walls or lie on the floor, but I like to think that I make lots of different things with my hands and mind. I got into this field initially because of inspiration that was fed from my first mentor at a local community college, Jerry Burchfield. This person was a light that referred to students as artists, and encouraged those artists to see and interface with the world as they did, not as they ‘should.’ Up until that point, I had only experienced this type of permission with my participation in the world of underground and punk music. I had never witnessed it before in academia. Because of the experiences that came with this, my work in education became of equal importance to my own artistic practice; where I am regularly touched, informed, and influenced by students — my fellow artists. I thrive on the reciprocal and multidirectional movement of energy and ideas, and crave taking part in collective thought, while thriving also on the spectrum of processes that others partake in.

We’d love to hear a story of resilience from your journey.

There was one period of time, a little over a decade ago, when I had commercial gallery representation through a dealer in New York. This relationship was the indirect result of some exposure that came from being part of a photography biennial in Houston, Texas. The art gallery absorbed this specific exhibition into its space, moving it from Houston to New York the following year. I had the pleasure of sharing this moment and its surrounding activities with several artists that I admire. The gallery exhibited and sold some of my work right out of the gate, before the opening reception. Within a few days, they offered formal representation. I was initially ambivalent about a new commercial relationship, but with some time and a sense of comfort and assurance, a relationship began to form.

Fast-forward to a period of time when I was crestfallen to learn that this gallery was selling artwork to collectors, real estate developers, and hotels all around the city without the knowledge or consent of their artists. My work was sold and distributed without awareness and also appeared in the spread of an architectural and interior design magazine based in Vancouver. The gallery had about five years worth of my material work, violated the contract, and would not return any pieces upon request or demand, ceasing all forms of communication. I had no legal representation like some of the other well-known artists on the roster did. This was a crushing several year period of time in my budding career. What follows is an epic tale about the things I did to successfully recover a portion of my artwork. It is a very long and intense story. I will spare those details. But the details do involve a car chase with a dear friend by my side, and a mountain of drama. This few year period required so much plasticity and endurance. The daily research at 4:00am every morning that was required to first locate as many pieces as I could filled several notebooks. I interviewed every former employee of the gallery, fishing out the smallest details. My remaining work was in storage in Chelsea, New Jersey, Long Island City, and Connecticut; perhaps elsewhere.

Deflated after this saga, I eventually pushed myself to realize that I needed to stop living in this recent and unwelcome past. What had to come next was the decision to not live with regret and distrust. I needed to move forward. For a period of time following, I really wanted nothing more to do with the commercial art world. But I needed to keep moving and growing and evolve in how I considered alternative directions with my practice and related opportunities. Developing the resilience and fortitude seemed the only rational alternative to walking away from that world altogether. I am at peace with most aspects of my practice and keep moving through this world and this field, not necessarily with elegance, but with integrity.

What can society do to ensure an environment that’s helpful to artists and creatives?

There are many things society can do to support a thriving creative ecosystem. But firstly, society would need to think that the arts and artistic cultures are a vital part of society, which is not often seen to be the case here in the United States. We need to be willing to put more resources and tax revenue toward national and local endowments, rather than expanding the resources towards things like harassing the unhoused or perpetually ballooning the Pentagon budget. Our culture tends to virtue signal about our various commitments to the arts and humanities, while our practical investments consistently wane. Cultural production cannot be solely be thought of as either potential commodity or else meritless. The arts are cultural resources. We need to feed bellies, mind, and soul in these fraught and culturally complex times. These are the periods in history where my sense of idealism widens.

In many ways the commercial marketplace is the forum that many young artists depend upon for visibility. That is the space where artists are perceived to be seen and rewarded. But that system alone alone is inadequate in representing the vast and diverse spectrum of cultural producers that our society is capable of generating. That system rewards only a small fraction of the work that is generated and their accompanying practitioners, and is not always merit based. We need other systems of support, a plurality of forums and formats. It has become an expensive world to navigate through and it is increasingly difficult to support truly experimental formats.

Too many educational institutions, corporate entities, cultural communities, et cetera, want to publicly claim their support for the arts, but do little to promote cultural, perceptual, and structural change. Since the beginning of my career, the majority of what I see are continual and progressive cuts as I scan across the systems that aim to support these cultural producers. We can definitely change these trends if we place real value on a creative ecosystem, vocalize support and vote accordingly.

I have faith in upcoming generations to help evolve our value systems.

Contact Info:

- Website: https://www.joeylehmanmorris.com

- Instagram: @JJJ_bird

Image Credits

Artists portrait, by Dr. Veronica Godoy-Carter

Artworks:

Empyrean Field I, by Joey Lehman Morris

Empyrean Field II, by Joey Lehman Morris

Empyrean Field VII, by Joey Lehman Morris

Empyrean Field IX, by Joey Lehman Morris