Alright – so today we’ve got the honor of introducing you to Jodi Colella. We think you’ll enjoy our conversation, we’ve shared it below.

Jodi, thanks for taking the time to share your stories with us today What’s been the most meaningful project you’ve worked on?

ONCE WAS is a memorial for all those lost to the opioid epidemic in the prime of their lives. A 12-foot, 2-sided panel is covered with 3600 poppies that are stitched and then sewn onto a plush black velvet foundation. Each poppy represents 200 people lost to the epidemic from 1999 to 2019. They are made from repurposed clothing donated by those I spent time with talking about the opioid crisis. The resulting array of patterns, colors, styles and materials represents the lives of people of every age, gender, relation, ethnicity, etc. The empty centers are outlined in bright red to embody the victims and the void reveals black velvet beneath – a funerary symbol – adding gravity and symbolizing loss.

I was one of eleven artists invited to participate in the exhibition Human Impact: Stories of the Opioid Crisis. We each worked closely with the museum, the sheriff’s department and a recovery center in creating a forum to discuss and learn the stories behind the crisis. I formed a relationship with a single mom who lost her son to a Fentanyl overdose. His story is like so many others where an unexpected dependence grew from a painkiller prescribed after an accident. The anguish and consequence of such a tragic loss of life is heartbreaking, and the horrifying fact is that this is only one family. In 2019, according to the National Institute on Drug Abuse, every day more than 130 people in the United States die after overdosing on opioids and it is estimated that there have been approximately 720,000 deaths between 1999 and 2019 due to opioid related substances.

It is striking to think that this monument only captures a moment in that particular time, especially since it required so much time and labor to create. The sad truth is that Once Was became obsolete the minute it was completed. The crisis is ongoing, and the casualties are mounting.

Great, appreciate you sharing that with us. Before we ask you to share more of your insights, can you take a moment to introduce yourself and how you got to where you are today to our readers.

My work is durational with a fetishist focus that embraces the ideals of labor and community. I’m attracted to color and texture, sourcing found domestic goods to create objects about loss and desire. Materials like grandmother’s quilts, wedding gowns, mother’s drapes and flannel nightgowns, dad’s plaid shirts, husband’s t-shirts, son’s striped dress shirt, furry remnants from toys and upholstery, the threads of unfinished needlepoint and embroideries, are objects embedded with a physical and symbolic history and show evidence of the hand. My curiosity about process has provided me with an encyclopedic knowledge of techniques, I’ve learned the rules and tools of the trades and then deconstructed them into unusual materials and expressive approaches. By practicing and pushing craft techniques I infuse a renewed power to handwork traditions. The manipulations of weaving, knitting, sewing, crochet, dyeing, embroidery, metalwork, and clay are each employed discriminately in the creation of my forms.

I’ve recently introduced ceramics to my repertoire of materials and techniques. Clay resists my control, softening my grip on external narratives and encouraging me to react instinctively. I commingle the rigid forms with fibers creating vessels that don’t hold water. Instead, they hold stories responding to family dynamics, loves, disappointments and celebrations and embrace domestic life with inquiry and self-discovery. They are lumpy, misshapen and lopsided, with cracks and orifices, fungible and porous to the world, embodying both the frailty and the strength of surrender.

Aspiring to David Pye’s Workmanship of Risk my works are not predetermined products controlled from the outset. Instead they depend on my judgment, dexterity and care during the process of making. It is the direct contact between me and the material that connects to earth and authenticity. I build in the rawness and state of unfinish to read as tenderness and challenge the pristine uniformity of mass-production as the nullification of expression.

My thoughtfully penned titles spotlight my personal, albeit universal, experiences. I work at breaking through the cacophony of artificiality and draw from the personal with honest expressions. As evidenced by the response to my recent exhibition But It Doesn’t Hold Water at Boston Sculptors Gallery, I have been successful in creating community connections with viewers who feel the same pain, elation and anxiety.

Is there mission driving your creative journey?

I mastered the precision and complexities of the needle arts early on during the summers of my youth when I was learning to both knit and swim. A dozen of us would sit in a circle on the hot rocks with our towels and stitch our lumpy scarves. The tools were simple pencils for needles, skeins of acrylic Red Heart yarn, and recycled Wonder Bread bags to carry them with. This early sense of community and innovation with craft is the primary influence and focus of my art making career. I have since facilitated many community efforts including founding the independent fiberarts study group FiberLab and multiple collaborative interactive installations. In the making, learning and supporting that happens within these groups, we embody the acts of craft and care with friendship.

We are products of who came before us, and like craft practices themselves, we inherit from previous generations. Traumas, celebrations, politics, and family behaviors are brought forward and captured into our physiologies and souls. One of my grandmothers raised six children as a widow in the postwar rural South. The other survived as an Italian Immigrant. Their legacies embody scarcity of opportunity, material goods, financial security, and love.

Growing up in their wake, and constituted of their genetic fiber, I feel a share of their sadness and joys. This is the source material I work with and I often wonder whether it is interesting to anyone but me. That is until I receive the kindred expressions and connections from my community who identify with the same feelings of being human.

My goal is to pursue expression, catharsis and collaboration by pushing materials, contemplating meaning and engaging in the lives of others. I hope to provide an antidote to loneliness and reinforce that we are not as alone as it sometimes feels. In the midst of the grief of the world, purpose can be sought when we place hand to clay, stitch to fabric, and an ear to the unheard.

For you, what’s the most rewarding aspect of being a creative?

Art gives me a purpose. It is a privilege to have an outlet for expression in a world that shuts you down. Recognizing this I use needle and thread to utilize materiality’s aesthetic and technical possibilities to effect societal awareness and change.

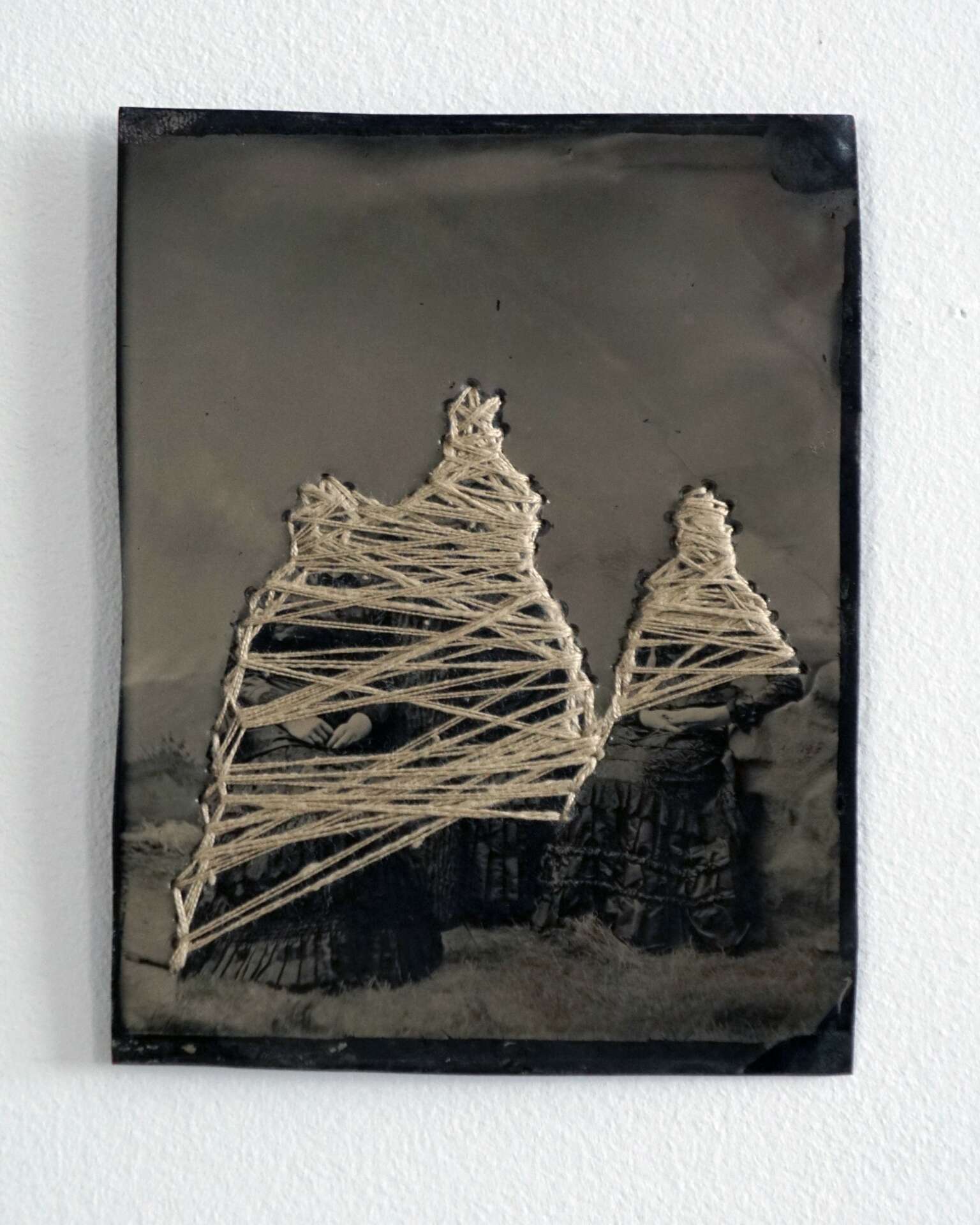

Needleart practices identify as feminine and have historically lacked the recognition received by formal art mediums. For instance, knowledge of who crocheted this doily, or stitched that heirloom quilt are lost by those who didn’t value the achievement. To spotlight the intricacies of forfeited identities I use the act of handwork to focus on the cultural tensions of identity politics, institutionalized prejudice and corporal agency. Feminist projects such as my tightly bound Mary Janes and the stitched tintypes of Unidentified Women speak to a history of loss, fracture and constraint, primarily in women’s lives. And the previously mentioned artwork Once Was represents the hundreds of thousands who succumbed to the greed of corporations giving priority to profits over human life.

These objects use the language of textile and craft to convey stories of protest, defiance, remembrance, and grief, of the silencing of women’s voices, the nullification of identity and autonomy, and the senselessness of the opioid crisis. They are examples of how art is an effective vehicle of communication for big ideas, sentiments and causes. It is a gift to engage in a practice of expressing through art, to touch and be touched by others.

Contact Info:

- Website: jodicolella.com

- Instagram: @fiberlab_diary

- Facebook: /jodicolella

- Youtube: @jodiarts

Image Credits

Will Howcroft Photography Julia Featheringill Photography Mike Spencer Photography Jodi Colella