We caught up with the brilliant and insightful Jingyi Zheng a few weeks ago and have shared our conversation below.

Jingyi, thanks for joining us, excited to have you contributing your stories and insights. What’s been the most meaningful project you’ve worked on?

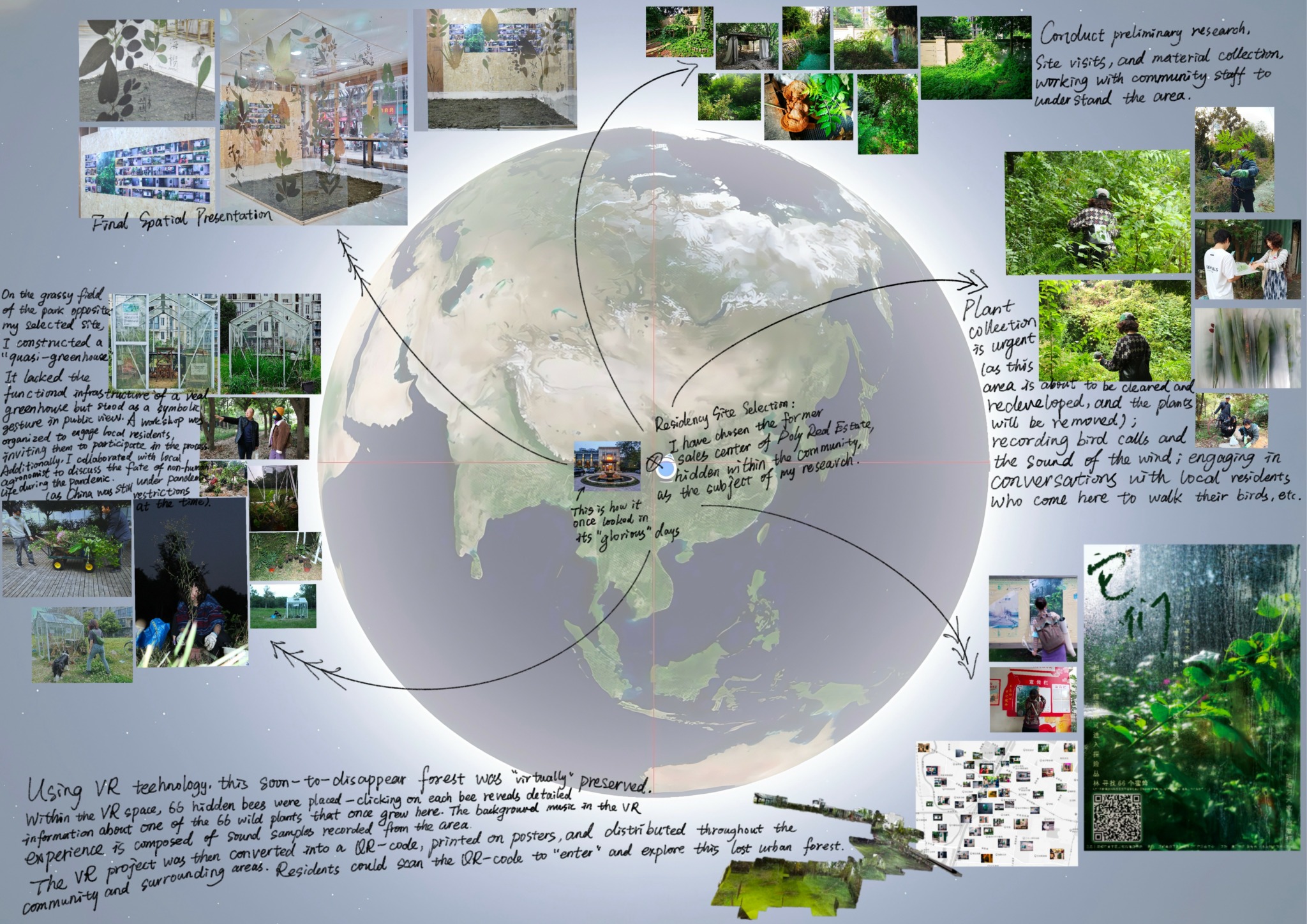

In 2022, I was invited (and recommended) to participate in a community artist residency project in Chengdu. The residency offered multiple locations where artists could conduct their research and creative practices. Without hesitation, I chose an abandoned real estate sales center, a decision that not only continued my previous creative trajectory but also led to new reflections throughout the residency.

This real estate sales center was originally developed by Poly Real Estate and once served as a commercial property showcase. Later, it was repurposed as a community garden restaurant, a hot pot eatery, and a senior canteen, before eventually being abandoned, transforming into a forgotten ecological void. Over time, the site became an unregulated “miniature forest”, attracting wild plants, birds, and urban wanderers. During my research on this space, I realized that, despite its past as a symbol of commercial real estate, it had now become a habitat for non-human life.

Initially, my decision to work here was tied to my long-standing interest in “dwelling spaces.” Since my time studying art in France, I have been exploring how humans define, construct, and commercialize the concept of “habitation.” After returning to China, I created an exhibition that used a real estate sales center as a model, employing absurdity to deconstruct the logic of the real estate market. When I learned that I could select a site for in-depth study during this residency, I was immediately drawn to this abandoned sales center—it embodied the legacy of urban planning and commercial space, while also standing at the precipice of imminent transformation.

However, as my residency progressed, my focus gradually shifted from human habitation to non-human habitation. In this decayed environment, plants emerged as the true protagonists. Resiliently growing through cracks in the crumbling concrete, they occupied the space left behind by human activity. I realized that their relationship with the city was not static but dynamic—they adapt, take root, survive, and, eventually, face erasure.

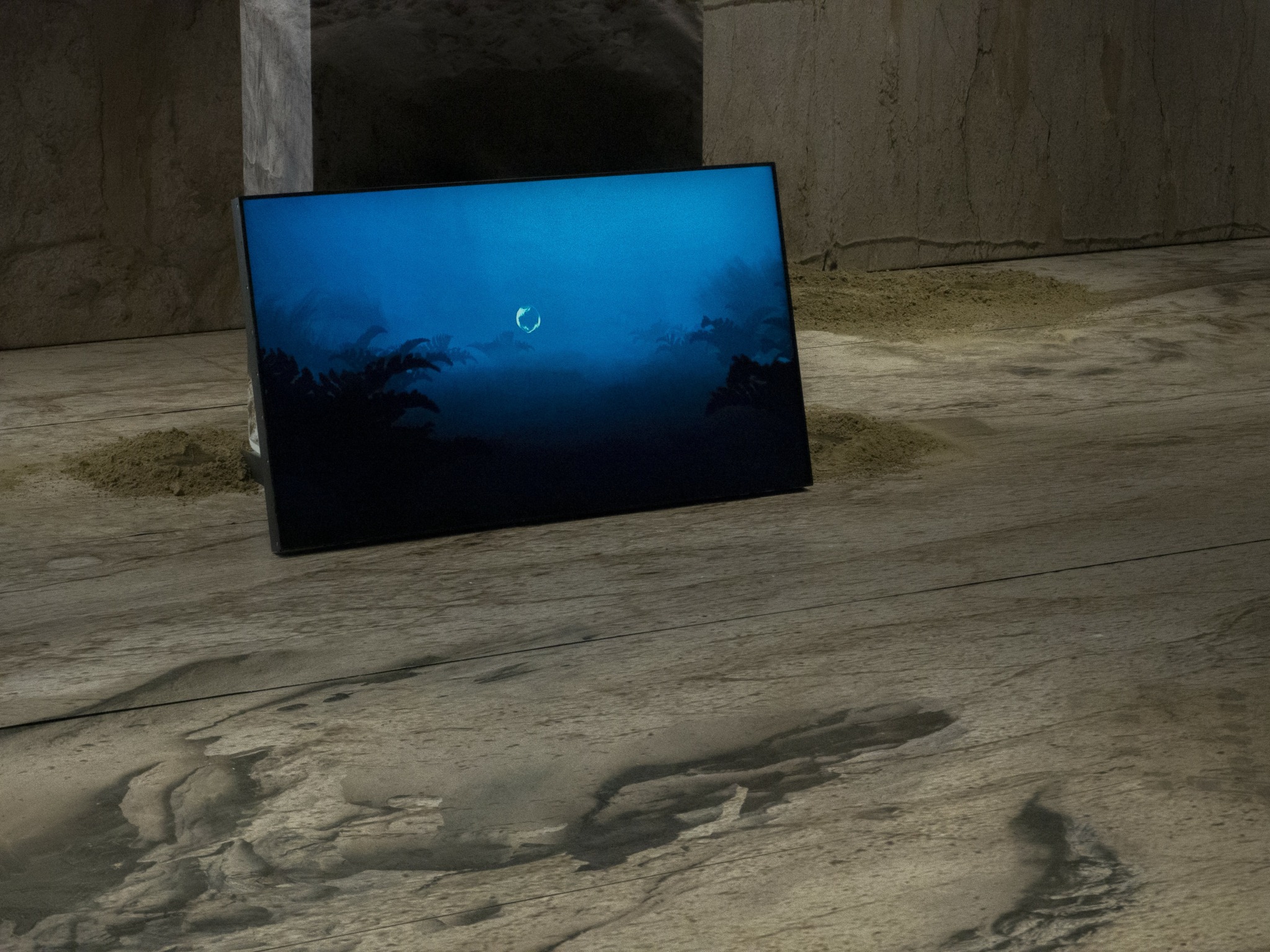

This realization led me to develop the “The Others” series, in which I employed VR technology to scan and archive these plants before they were removed, preserving their presence in a digital world. This process prompted me to consider whether non-human life, as physical spaces are continually developed and reshaped, could find an alternative form of “existence” through digital technology.

Toward the later stages of my residency, I was informed by the community management that this area would soon be fenced off and redeveloped. They even suggested that I relocate to another site to avoid disruptions. However, by then, I had already formed a deep connection with this ecosystem and decided to stay and complete my work alongside these soon-to-be-erased plants.

To explore this subject further, I developed three distinct artistic approaches during my residency:

• “The Others I – Preservation”: Using VR technology to scan and archive these plants, ensuring their virtual survival even if they were physically removed.

• “The Others II – Transference”: Constructing a “pseudo-greenhouse” in a nearby park, transplanting some of the endangered plants to observe their adaptation to a new environment.

• “The Others III – Recomposition”: Deconstructing and reconstructing plant images within the exhibition space, creating “new plant species” to explore how plants are redefined within artificial environments.

This residency fundamentally changed my understanding of what it means to “inhabit.” The notion of dwelling is not exclusive to humans; non-human life forms also continuously seek places to settle. However, in the rapid urbanization process, these survival strategies are often overlooked, if not actively erased.

Through this experience, I became more committed to examining marginalized ecological existences in urban environments—investigating how non-human life adapts, resists, or redefines its place in the city. This exploration significantly influenced my later “The Others” series and deepened the themes I would pursue in subsequent exhibitions and research. In 2024, my two solo exhibitions, “Exit in the Wind” (at The Galaxy Museum of Contemporary Art, Chongqing) and “Stupid Us and Them” (at C-PLATFORM, Xiamen), extended this investigation further. These exhibitions explored the persistence of non-human living spaces, integrating installations, video works, and virtual reality to construct an artistic system that examines how marginal plants are observed, preserved, and reconstructed.

Meanwhile, I continue to observe “wildly inhabited” urban spaces—those overlooked corners, unused plots, or soon-to-be-demolished ruins, all of which, at some point, may face the fate of removal. Even though the real estate sales center I worked in no longer exists, my research continues, and so does my creative practice.

This line of inquiry will persist into future projects. In 2026, I plan to undertake an artist residency in the Tianshan Mountains of Xinjiang, where I will study survival strategies of non-human life in extreme climates, juxtaposing them with the marginal plants I have been researching in urban environments. This will serve as an important expansion of my work on non-human habitats, offering new perspectives for my future creations.

The Chengdu residency was not just a temporary artistic experiment but an ongoing research trajectory. It led me to shift my focus from human habitation to non-human habitation, prompting me to explore the unnoticed lives that persist within the cracks of the city, questioning how they adapt, how they are defined, and how they disappear.

Even though the real estate sales center no longer stands, my research remains active. I continue to search for these neglected ecological spaces and explore how art can make them visible again. My practice, much like the wild plants I study, does not stop—it continues to grow, adapt, and spread, until one day, they finally find a place of their own.

As always, we appreciate you sharing your insights and we’ve got a few more questions for you, but before we get to all of that can you take a minute to introduce yourself and give our readers some of your back background and context?

I am Jingyi Zheng, a contemporary artist whose work explores the entangled relationships between humans and non-human life forms, focusing on urban ecology, spatial transformation, and digital preservation. I was born in Sichuan, China, and later pursued my artistic education in France, earning both my Bachelor’s and Master’s degrees from École Supérieure d’Art et de Design Le Havre-Rouen, where I graduated with the highest distinction. Currently, I live and work between Chengdu and Chongqing, actively engaging in artistic research, residencies, and exhibitions.

My practice operates at the intersection of nature, technology, and the built environment. I investigate how non-human entities—particularly plants—adapt to urban spaces, often in overlooked or soon-to-be-erased areas. My work takes shape through installation, video, 3D modeling, digital archiving, and artist’s books, creating dialogues between the physical and the virtual, the remembered and the forgotten. Through speculative research and artistic interventions, I document and reimagine the survival strategies of plants within shifting urban ecologies, challenging anthropocentric narratives of space and habitation.

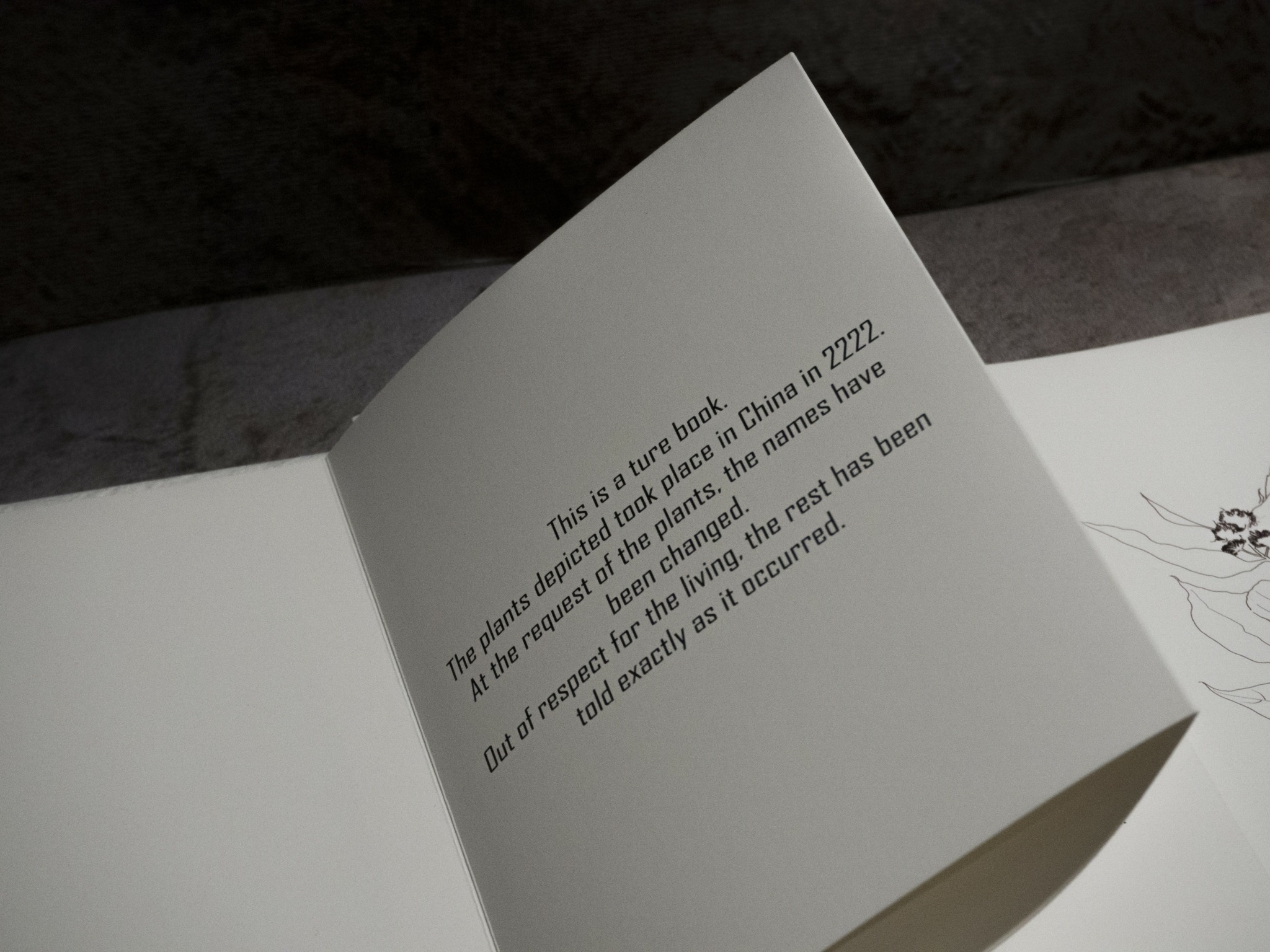

A distinctive aspect of my work is the integration of artistic storytelling with scientific methods and digital technology. Rather than simply representing nature, I utilize VR scanning, speculative cartography, and conceptual publishing to preserve, reconstruct, and reinterpret ecological narratives. My “The Others” series, for instance, archives plant life from abandoned urban sites facing redevelopment, allowing them to “persist” in digital space even after their physical disappearance. Similarly, my artist’s books function as fictional archives of future ecologies, blending visual and textual elements to question notions of naming, memory, and the rights of non-human life.

Through my work, I invite the audience to reconsider their perception of urban nature and question the power dynamics between human development and ecological resilience. Whether through installations, moving images, or experimental publications, my projects encourage engagement with hidden ecosystems, transient landscapes, and the possibility of coexistence beyond human-centric frameworks. My ongoing research extends into upcoming residencies and exhibitions, further exploring how we can rethink preservation and habitation in both the natural and digital realms.

Is there something you think non-creatives will struggle to understand about your journey as a creative?

One of the challenges non-creatives might struggle to understand is that my creative process is not linear, nor is it solely centered on the final presentation of a work. Unlike professions with clear career trajectories, artistic creation is often a long-term research-driven practice. It does not yield immediate, tangible results but rather unfolds as an ongoing process of fermentation. My projects typically involve field investigations, ecological observations, theoretical research, and conceptual development—all of which may take years before materializing into a completed work. Throughout this process, my focus may shift, and my research methods may evolve in response to changing environments and societal issues.

For example, my research on the habitation of non-human life in urban spaces began as a single artist residency but gradually expanded into exhibitions, publications, and even an ongoing speculative archive of the future. This process is not just about producing artworks; it is an experiment in how knowledge is preserved, reinterpreted, and shared.

Another common misconception is that artistic creation relies on sudden bursts of inspiration, when in reality, it is a highly structured process of research and experimentation. My work involves artistic interventions, scientific methodologies, and digital preservation technologies, with each project rooted in site-specific investigations, interdisciplinary dialogues, and material experimentation. Much of this research-based labor remains “invisible” to the outside world until the final work is presented, but to me, the research itself is already an integral part of the creative process.

During my residency in a local community, I experienced this disconnect firsthand. I frequently had to communicate with community staff and local government officials, explaining my research direction and artistic approach. Although I articulated my methodology as clearly as possible, they still could not comprehend why I had chosen an abandoned real estate sales center as my research site. To them, this area was a “blemish,” a neglected and overgrown space—a place they considered messy and undesirable, one that should be rectified rather than studied, documented, or used as the focus of an artistic practice. They preferred to align artistic projects with community beautification, cultural promotion, or environmental governance—tangible and visible results, rather than engaging with an artistic inquiry focused on forgotten and overlooked spaces.

Toward the later stages of the residency, they even suggested that I redirect my research into a “botanical education” project, introducing local residents to the plant species growing in the thicket. However, my work is not about environmental education, nor is it strictly ecological art. While my projects engage with nature, ecology, and environmental themes, they are not about conservation advocacy or scientific knowledge dissemination. Instead, I use marginal plants as an entry point to explore broader existential conditions—not just their fate, but ours as well.

When the community administrators proposed reframing my research as “nature education,” their response reflected a larger societal issue: How do we perceive non-human life? Are we only capable of understanding it through a functional framework, or can we engage in more open-ended, politically and philosophically complex discussions? This realization made me even more aware that artistic creation is not only about presenting works but also about challenging systems of understanding, reshaping dialogues, and prompting new ways of thinking about the world. Confronting this challenge, my work is not just about research, creation, and exhibition—it is also about engaging in an ongoing conversation, and at times, resistance, against rigid societal perceptions.

At its core, an artist’s journey is not just about producing visible objects; it is about learning to listen—to listen to spaces, to listen to non-human life, to listen to history and the future—and to translate these observations into new perspectives that encourage people to reconsider their relationship with the world.

In your view, what can society to do to best support artists, creatives and a thriving creative ecosystem?

To truly support artists and the creative ecosystem, society must go beyond superficial recognition of art and establish a long-term, sustainable support system that enables diverse forms of artistic practices to develop—not just those that serve the market or institutional demands.

First and foremost, reducing political censorship and fostering inclusivity and collaboration is essential. In China’s artistic ecosystem, creators must navigate not only market and institutional selection processes but also a delicate balance between “safety” and “experimentation.” The presence of political censorship does not only limit direct expressions of social issues but also encourages self-censorship among art institutions, leading to a closed ecosystem that suppresses truly experimental practices.

Beyond policy adjustments, society’s perception of art must also evolve. We need a deeper cultural dialogue where the public, communities, and governments no longer see art as merely decorative or functional but understand its role in critical thinking, reimagining reality, and envisioning the future. The lack of this understanding often results in artists’ work being misinterpreted, instrumentalized, or expected to conform to certain social expectations, neglecting the critical and experimental nature of art itself.

Additionally, we need a more diversified support system, which should include but is not limited to:

1. Expanding Art Funding Systems to Support Research-Based, Cross-Disciplinary, and Non-Traditional Media Practices

Currently, many funding programs and institutions still primarily support traditional exhibition models, while research-driven, interdisciplinary, or digital practices struggle to receive equivalent backing. Society should broaden the structure of funding systems, residencies, and art grants to be more inclusive, encouraging experimental creations that challenge existing frameworks and break conventional classifications.

2. Promoting Cross-Disciplinary Collaboration to Strengthen Dialogue Between Art, Technology, Ecology, and the Humanities

Art has never existed in isolation. Many of the most influential projects emerge at the intersection of art, science, ecology, and technology. Establishing platforms for cross-disciplinary collaboration—where artists engage with scientists, urban planners, ecologists, and sociologists—can lead to the creation of more meaningful and socially relevant artistic projects.

3. Supporting Localized and Site-Specific Art Practices Beyond the Museum System

The current art support system is often overly concentrated in large institutions and international exhibition circuits, overlooking community-based, urban fringe, and informal space-based artistic practices. Society should place greater emphasis on how art intervenes in public space and affects real-life conditions, rather than confining it solely within exhibition venues.

4. Strengthening Independent Art Publishing and Knowledge Systems

Many artists—especially those working in artist’s books, fictional archives, and conceptual publishing—extend their artistic practice through publications. However, independent publishing still faces funding and distribution challenges. Society should support more experimental publishing projects and interdisciplinary archival initiatives, ensuring that art is not only something exhibited but also a means of knowledge circulation and critical inquiry.

5. Integrating Artistic Research into the Broader Knowledge System

In contemporary society, scientific and academic research are often highly valued, while the significance of artistic research is frequently overlooked. However, art is not merely a form of expression—it is also a unique research methodology that uncovers overlooked narratives, raises critical questions, and stimulates multidimensional thinking. If artistic research were granted the same recognition and funding as scientific research, it could contribute profound insights into culture, history, and ecological understanding.

A truly effective support system for the arts must go beyond simply funding exhibitions—it must invest in the full process of artistic thinking, experimentation, and knowledge production. Only when society understands that art is not just about creating objects but about offering new ways of perceiving and understanding the world can we cultivate a genuinely thriving, diverse, and intellectually rich creative ecosystem.

Contact Info:

- Instagram: jingyi_jeanguy

Image Credits

By Jingyi ZHENG