We recently connected with Jeri Fonté and have shared our conversation below.

Jeri, thanks for joining us, excited to have you contributing your stories and insights. It’s always helpful to hear about times when someone’s had to take a risk – how did they think through the decision, why did they take the risk, and what ended up happening. We’d love to hear about a risk you’ve taken.

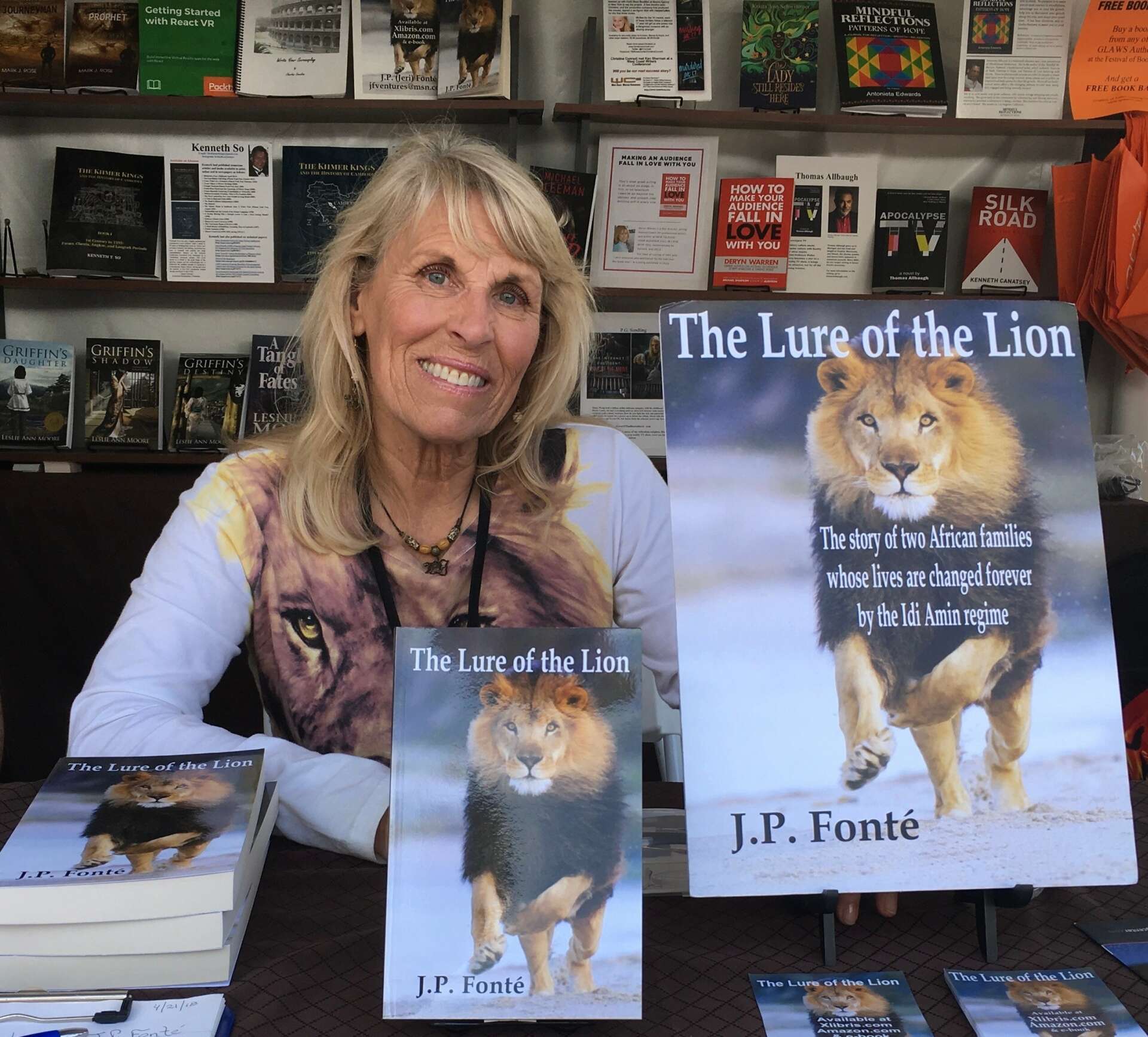

Most of the risks I’ve taken have had serendipitous results. The first major one was leaving American Airlines after four years as a stewardess/flight attendant. I left to travel on my own, in what could be called “a year of living dangerously.” With my only contact being the address of an agency that placed young women as “au pairs,” and without knowing much more French than “Où sont les toilettes,” I moved to Paris for six months and became employed by a fabulous family. Then, when arriving in Israel to volunteer on a kibbutz, again with just the address of a placement agency, I serendipitously connected with two American girls I’d previously met at a youth hostel in Brussels and followed them to the kibbutz they’d been assigned. As happened in France, it also had a fortuitous outcome. Later in life, following a divorce and with my two then-teenaged sons in tow, I spent another potentially “dangerous” year abroad, predominately in Africa, researching a historical romance novel titled The Lure of the Lion. I’ll always be grateful for my employment with American Airlines, which gave me the courage to venture into the world, but it’s my parents who instilled in me an adventurous spirit, and gave me the emotional support to pursue my dreams. They also nurtured the concept that a person’s worth is measured by who they are, rather than what they are. And my love and respect of animals was encouraged and in large part realized because of them, which is what led to my adventures in Africa.

Jeri, before we move on to more of these sorts of questions, can you take some time to bring our readers up to speed on you and what you do?

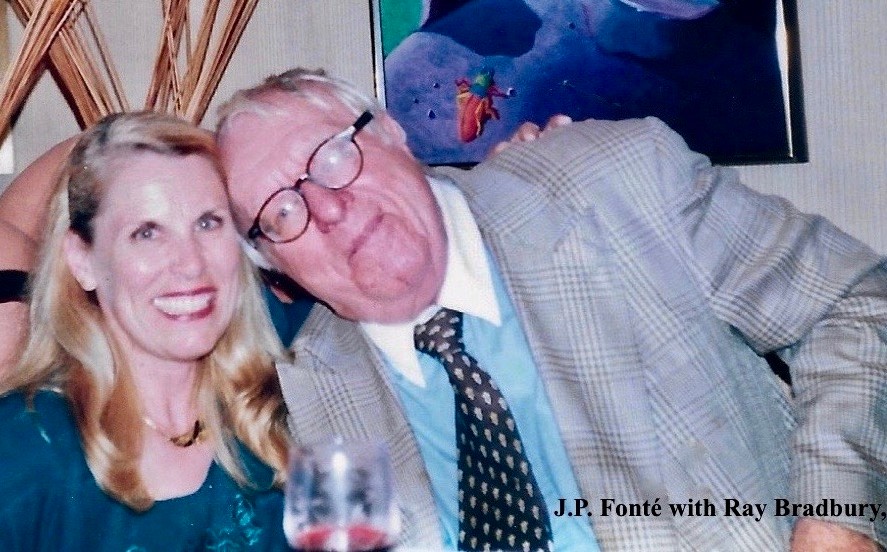

When I was a flight attendant, I won the first-place “door prize” at a required safety meeting — two tickets anywhere Pan Am flew. Because of my love of animals, I used them to go to East Africa. My traveling partner and I prearranged a ten-day safari, followed by a week to “play-it-by-ear.” We were going to go to Mombasa, to lie on the beach and just relax, but elephants had torn up the water lines leading to town, so we went to Uganda instead. One of the tourists on our organized trip to Kenya and Tanzania had been there and raved about it. In Uganda I found the Africa I was seeking. Later, learning of the atrocities of the Idi Amin regime and deeply concerned about its effects on both the people and wildlife of Uganda, a story evolved in my mind that became the novel The Lure of the Lion. I didn’t grow up wanting to become a writer/author. It wasn’t until I had a story I felt compelled to write, and was worth doing so. I refer to it as my “third child,” with a twenty-year gestation. The biggest help I received in realizing its publication was through the organization Southwest Manuscripters, with its claim to fame having Ray Bradbury as its figurehead. At that time, there were few options for reputable self-publishing, and the technology for DIY wasn’t yet developed. Wanting to hold onto the copyright, I was opposed to it being traditionally published. The company I went with, Xlibris, is one of the few still in existence. Today I’m the program director for Southwest Manuscripters, and have the opportunity to interact with writers in all levels of proficiency. Located near Los Angeles, I invite others to join us in-person or virtually — to help in the continuation of the oldest functioning writers’ group west of the Rockies.

How can we best help foster a strong, supportive environment for artists and creatives?

As a “boomer” I was able to experience a time when “The American Dream” was much easier to achieve, while also taking a road other than the accumulation of material wealth was encouraged. I feel that ideology, and opportunities to do so, no longer applies, especially economically. When I was younger, I never considered myself politically inclined. But I’ve come to realize the extent to which politics affects every aspect of life, from the quality of the air we breathe and the water we drink, to the protection of one of the most basic human rights — that of bodily autonomy. It’s disturbing to which politics has been manipulated and plays a major part in discouraging individual creative endeavors, specifically through book banning, the attempt to abolish libraries, and establishing policies that favor corporations and enable the commercialization of entities like education and healthcare. As with other interests, perhaps the best way to achieve support for artists and creatives is through the ballot box — in electing officials who recognize the importance of their contribution to society.

What’s the most rewarding aspect of being a creative in your experience?

I feel the desire to be artistically creative is an innate human quality, but has been diminished by societal expectations and strictures. For me, the most rewarding aspect of being a creative is the sense of fulfillment from producing something reflective of my individuality — something self-generated, not imposed, and which could be beneficial to others.

Contact Info:

- Facebook: J.P. Fonté

- Linkedin: Jeri Fonté