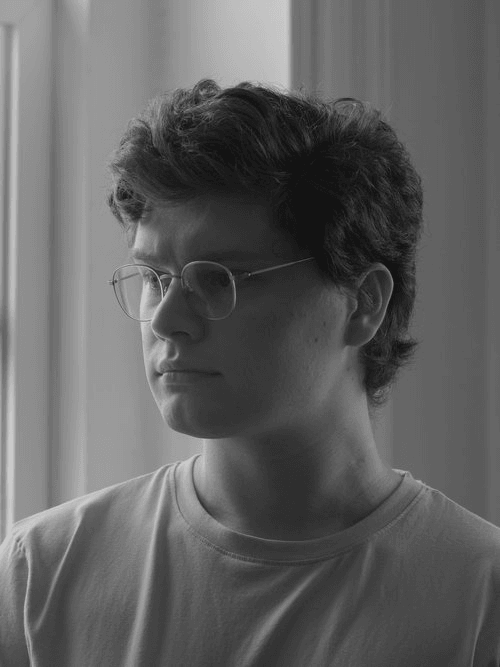

We caught up with the brilliant and insightful Jeff Smudde a few weeks ago and have shared our conversation below.

Jeff, thanks for joining us, excited to have you contributing your stories and insights. Did you always know you wanted to pursue a creative or artistic career? When did you first know?

I started taking pictures very young. When I was a kid, I bought a point-and-shoot film camera at a garage sale a neighbor was having – a whole $2 well spent. I would take photos of my friends and cousins when playing, and once I took it to a summer camp, I took a couple photos that to this day I still find truly amazing how good they are (especially for a kid). Some years passed and I took a darkroom photo class in high school. My teacher saw that I had a distinct interest in photography, meanwhile I was trying to set myself up for going into graphic design for my college years shortly thereafter. I still have those negatives from high school (as well as those from that summer camp as a kid).

Once I started undergrad at Illinois State University, which I knew had a great graphic design program, I was ready to go into a field that I still feel passionately about – the music industry – doing visual art for albums, tours, promos and so on. I was a double major, graphic design and music business. Everything felt like it was on-track the way I planned in high school. That was my first mistake! Things seldom go as planned, and once I started taking more art studio and art history classes, that became more prominent, that things not going as planned is par for the course in visual art.

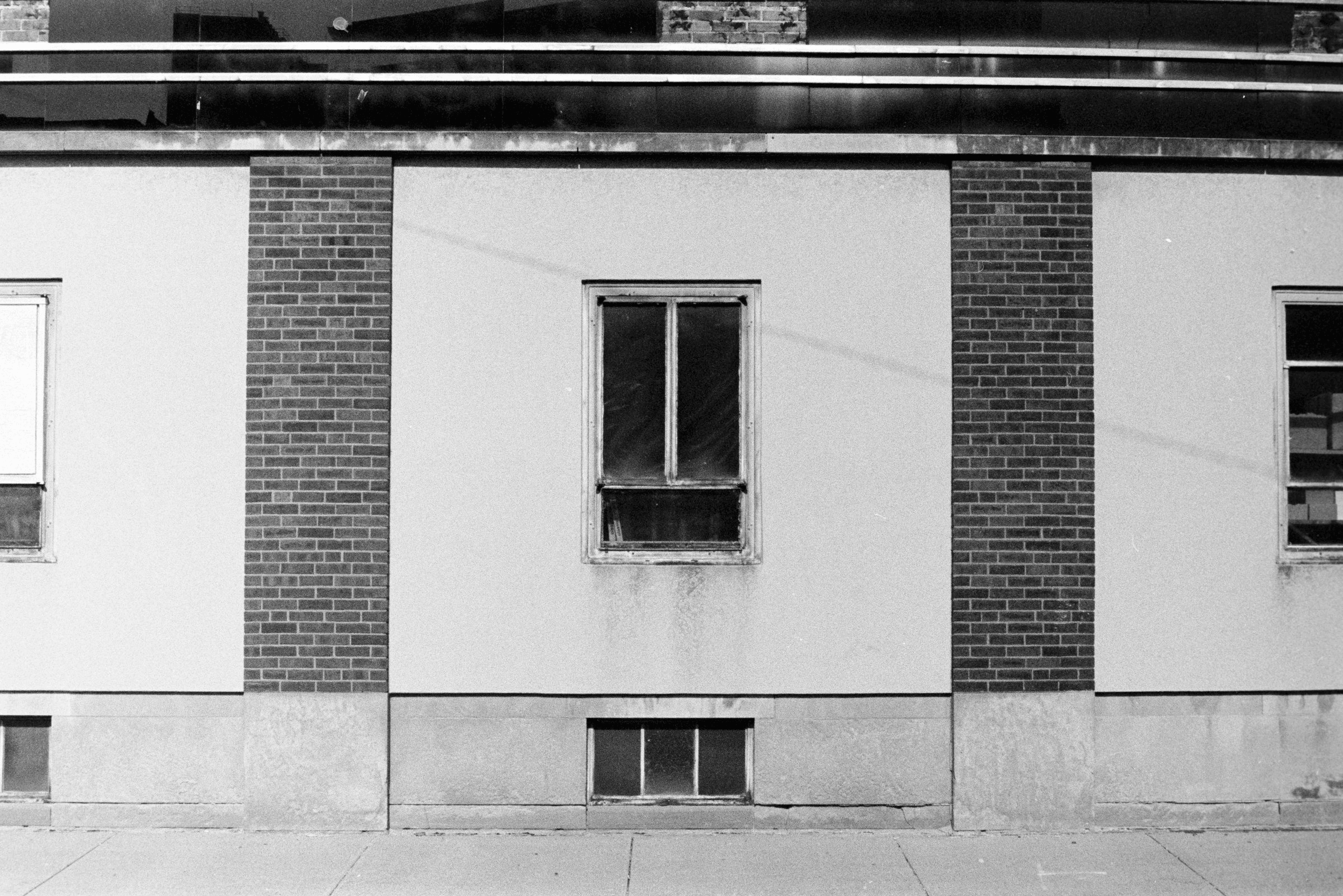

By the second semester of my freshman year at ISU, I was in a photo class with professor Jason Reblando – a wonderful teacher and artist interested in documentary methods. My class with Jason was another darkroom course, a requirement for graphic design majors, and suddenly I felt more joy taking photos than I did drawing thumbnails for GD. I made a series of architectural landscapes in Bloomington, Illinois and surrounding towns for my final in that class. The work calls to mind the likes of Bob Thall, Lewis Baltz, Robert Adams, Walker Evans, and others of their generations.

Clearly something clicked for me. The beginning of my second year at ISU was met with a bit of a crisis — I had re-fallen in love with photography since high school but I didn’t want to go through the hassle of changing majors. After talks with my advisor and friends, I realized that doing just that was the right move. I already had a developing eye for photographs and the foundation classes are the same between GD and photo. I had also kicked music business to the curb, realizing that those opportunities can come through networking rather than a degree if I want to do visual art for music.

I remember walking home from the meeting with my advisor when I officially changed to photo – I had the biggest smile on my face, laughing a little to myself. It was pure, honest joy. From there on, I studied among three amazing artists — the forementioned Jason Reblando, then Jin Lee and Bill O’Donnell. A true powerhouse of artist-teachers that showed me the way to fine art photography, understanding how to listen to my own interests and put that into my photographs.

Jeff, before we move on to more of these sorts of questions, can you take some time to bring our readers up to speed on you and what you do?

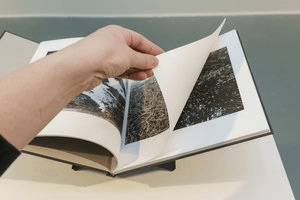

I grew up in the Midwest, most of the time in Illinois, which is not known for its photogenic scenery (but trust me, it is there!). I originally wanted to go into the music industry doing visual art for bands and individuals, but I found a more distinct interest in that of photo books, curating, educating and connecting with other artists. My professors in undergrad at Illinois State University would often bring photo books in to class, sometimes of artists they know personally. Seeing many Midwestern photographers making such beautiful, meaningful work and putting it into the world in book form struck a chord with me.

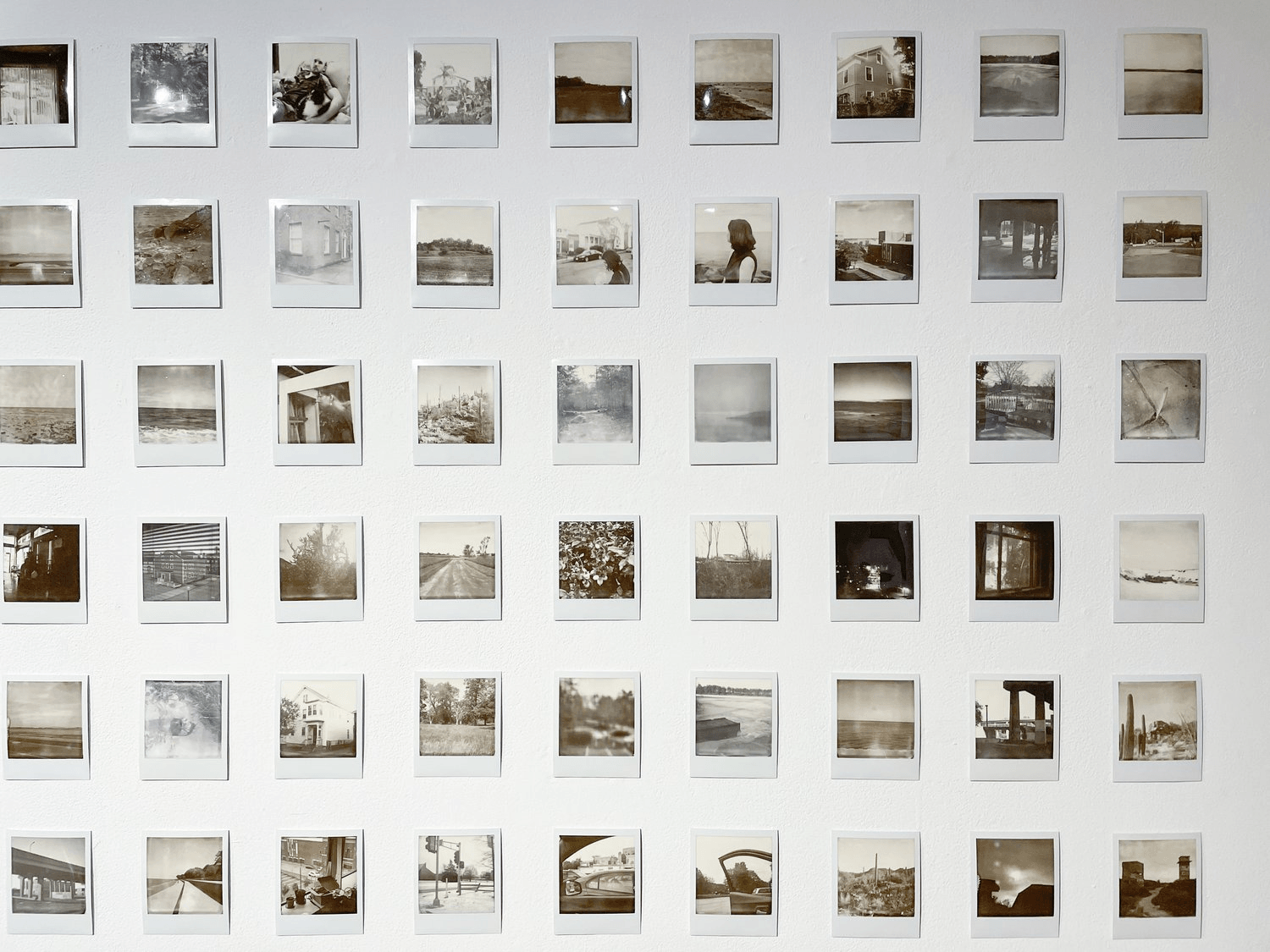

I started making my own photo books and zines later after undergrad. Often times they would be digital only, experimenting with sequence and visual design elements. Later, I would curate some submission-based zines (Such as “Nothing is Interesting and Everything is Normal” and later “I Can Hear the Road Call”). Working with other artists’ works was an eye-opening experience. Seeing relationships between artists who likely don’t know each other, if even of each other, taught me a lot about how photographs function in a conceptual sense. I have been wanting to do another one of these curated, submission-based zines, but with a busy schedule, it has be put on the back-burner.

In 2019, months before COVID-19 was even a thought in the American psyche, I decided to start a podcast to interview artists. I started with some friends of mine, some of those episodes are still up, others will be re-recorded as things have changed for them drastically. The show is titled “Ready for Mistakes,” which came from a realization that there comes a point in an artist’s life where they realize after years of learning the “rules” and formalities of the media they work in, there comes a time where you are “ready to make mistakes.” To break free from expectations even if you still abide by some rules built up on in younger years. This show took a pause while I prepared for and went to grad school for photography, and later was started up again after I finished my MFA at University of Massachusetts Dartmouth. I interviewed artists such as Epiphany Knedler, Nathan Pearce, Lindsay Godin and Meggan Gould, and plenty more artists are lined up for future episodes. These conversations serve both to learn about the individual on the video call with me, but also to learn about contemporary practices of those artists who aren’t so prominent in the photography world yet. I always hope these conversations will teach the listener not only those things, but also how to apply different thought processes to their own work.

At the end of the day, outside of my personal art practice, I want to educate people on photographic art and its possibilities. Both of my parents had gone to college, and my dad is a professor, which has instilled a passion for education (especially that of higher ed) into my mind. I’m always looking for opportunities to teach people, even passively, about photography and encouraging experimentation, practice, and beyond. Education of all kinds is essential to society, and more importantly accessible education. I found in many of my art history and theory classes that there are so many texts that are often read in these classes that have a style of writing that is difficult to understand, which builds up a wall between the content and the reader. These texts become inaccessible, hard to have conversations about, especially if they are many decades old and certain ideas do not resonate with a contemporary mindset. Additionally, it goes to that of writing on contemporary art that builds up a wall of art-speak that is near impossible to understand for a student who only just started to learn about fine art as a whole. It’s not even a reading level problem, it’s a semantic and linguistic issue that I, and very many of my peers, are working to break down and bring accessible art education back into the curricula of schools, organizations and artist groups around the country.

How can we best help foster a strong, supportive environment for artists and creatives?

As I’ve already mentioned, accessible art education is a big part of it. Additionally, art is not an easy field to get into financially, regardless of medium. Photography is notorious for being very expensive, even if you have a fairly affordable camera setup, there’s so many more expenses beyond the camera itself that makes it hard to work in. There are grants, scholarships and more that can help, but the inherent issue with those is they become competitive. When you apply to a grant for $5000 to work on a project, or you shoot high and try for a Guggenheim fellowship, you’re up against so many other artists and you don’t have any idea what is going on in the minds of those who are deciding who will get the money.

From my perspective, there’s a huge double-standard in American society around artists of all kinds. We see simultaneously a great importance put on artists (especially those of celebrated artists), in music, fine art, literature, etc., but we will also see schools getting their art program funding cut. This happens in primary schools and colleges alike. I’m grateful that my high school had two photography classes and a working darkroom, and it’s likely one of the last of its kind as so many high schools are losing not just darkrooms and photo classes, but art classes all together. Along with that, teachers are not paid enough, especially public school teachers. A college professor teaching full time may do alright, but a high school art teacher will get the short end of the stick even though they both teach at government-funded public schools. This begins to get into a much bigger issue, so I won’t start going on about topics that I still have much more to learn about.

Society can help artists by making things more accessible and supporting those who teach artists at any level.

Are there any books, videos, essays or other resources that have significantly impacted your management and entrepreneurial thinking and philosophy?

The first photo book I saw that truly got me emotional was Alice Hargrave’s “Paradise Wavering.” I had already been exposed to the likes of Alec Soth, Stephen Shore, Nan Goldin and many of the prominent artists from the 70’s to early 2000’s, but Hargrave’s work made me feel something that I didn’t know was possible — that a sequence of photographs could get one to tear up, to feel your heart “buzz.”

Later, I was introduced to what I believe to be Alec Soth’s best work, “Broken Manual,” an elusive project held by many high education institutions’ libraries special collections. This work of Soth’s began to break rules left and right, with imperfect pictures, heavily cropped-in works, that all work together to build an “incomplete” guide on how to disappear form society (hence the title, “BROKEN manual”). This book sticks with me and the only copy I have access to is in his recent publication of “Gathered Leaves: Annotated.”

I had also read Geoff Dyer’s “The Ongoing Moment,” which is a fascinating look at photographic history and the nuances of place and time. It’s a very accessible book that has a structure of following photographic subjects rather than chronology or specific individuals (though both of those are still important in the text).

Finally, Rebecca Solnit’s books “Wanderlust” and “Field Guide to Getting Lost” became integral in understanding my interests in art. With my personal work being about place — both physical and mental — Solnit’s books explore both of these types of place in such a beautiful way. She pulls from both her personal life history and history as a whole to build her ideas of walking, what it means to get lost intentionally, the affects that can happen when someone explore things in this way. That photographers especially have a knack for getting lost in one way or another, to wander about mentally or physically. These books really point to what can happen for you when you embrace these things.

Contact Info:

- Website: https://www.jeffsmudde.com

- Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/jeffsmudde/

- Linkedin: https://www.linkedin.com/in/jeffrey-smudde/

- Youtube: https://youtube.com/c/jeffsmudde

Image Credits

All photographs by Jeff Smudde