We’re excited to introduce you to the always interesting and insightful Jee Won Kim. We hope you’ll enjoy our conversation with Jee Won below.

Jee Won, thanks for joining us, excited to have you contributing your stories and insights. What’s been the most meaningful project you’ve worked on?

This question made me reflect on what has truly been the most meaningful experience in my musical life. These days, I’ve been organizing several concerts as a co-founder and co-artistic director, and at first, I thought it might be interesting to talk about those recent projects. However, the more I thought about what “meaningful” really means to me, I realized I should talk about my very first piece written in the United States, 염원 Longing, because it shaped me into the composer I am today and opened up my musical perspective in a completely new way.

In 2018, I began my master’s degree at the Manhattan School of Music, where my professor, Reiko Füting, emphasized from the very first class the importance of experimentation in music. I had always wanted to try writing atonal music using extended techniques like those used by renowned composers, but I was afraid to begin because I didn’t know where to start or what kind of results it might bring.

I don’t know where I suddenly found the strength at that time, but somehow, I gained the confidence to experiment. Maybe because if I did something “wrong,” Reiko would have told me. So for the first time, I wanted to take risks and try everything I hadn’t tried before. Of course, there were still a few things I wanted to keep which gave me a sense of stability, such as using instruments I was somewhat familiar with and setting a Korean poem whose story I knew I could express with my musical voice.

The piece is based on the Korean poem “Geo-mun-go (거문고)” by Young-Rang Kim, written in 1939. I used Hanji (traditional Korean paper) as both an instrument and a medium that connects the audience with the poem. I also wanted to explore sounds that I hadn’t used on the other instruments. To explore new sounds, I began to focus less on musical lines and more on the instruments themselves, asking: What kinds of sounds can each instrument make? What makes each one unique? I met frequently with my performer friends to experiment with new techniques and unconventional sounds. Writing this piece required an enormous amount of time and support from them, which is what I appreciate most about this project.

After five months of experimentation and close collaboration with my performer friends, I finally completed “염원 Longing.” Stepping out of my comfort zone was not easy at all, but I consider it a great success. Not just because I received wonderful comments from the audience after the concert, but because I gained the courage to believe that experimentation can bring out an even deeper, more personal voice. My view of music changed completely. I began to see music as a sphere beyond something purely auditory, and I developed a desire to create works where sound is complemented by visual and tactile elements, allowing people to experience music in diverse ways. Now I am no longer afraid of experimenting with sound. That is why this piece means so much to me.

Awesome – so before we get into the rest of our questions, can you briefly introduce yourself to our readers.

My name is Jee Won Kim and I am a South Korean composer based in the United States. I came to the US in 2018 to pursue my Master of Music degree in Composition at Manhattan School of Music, and I am currently in Bloomington, Indiana, finishing the dissertation for my Doctor of Music degree at Indiana University Jacobs School of Music.

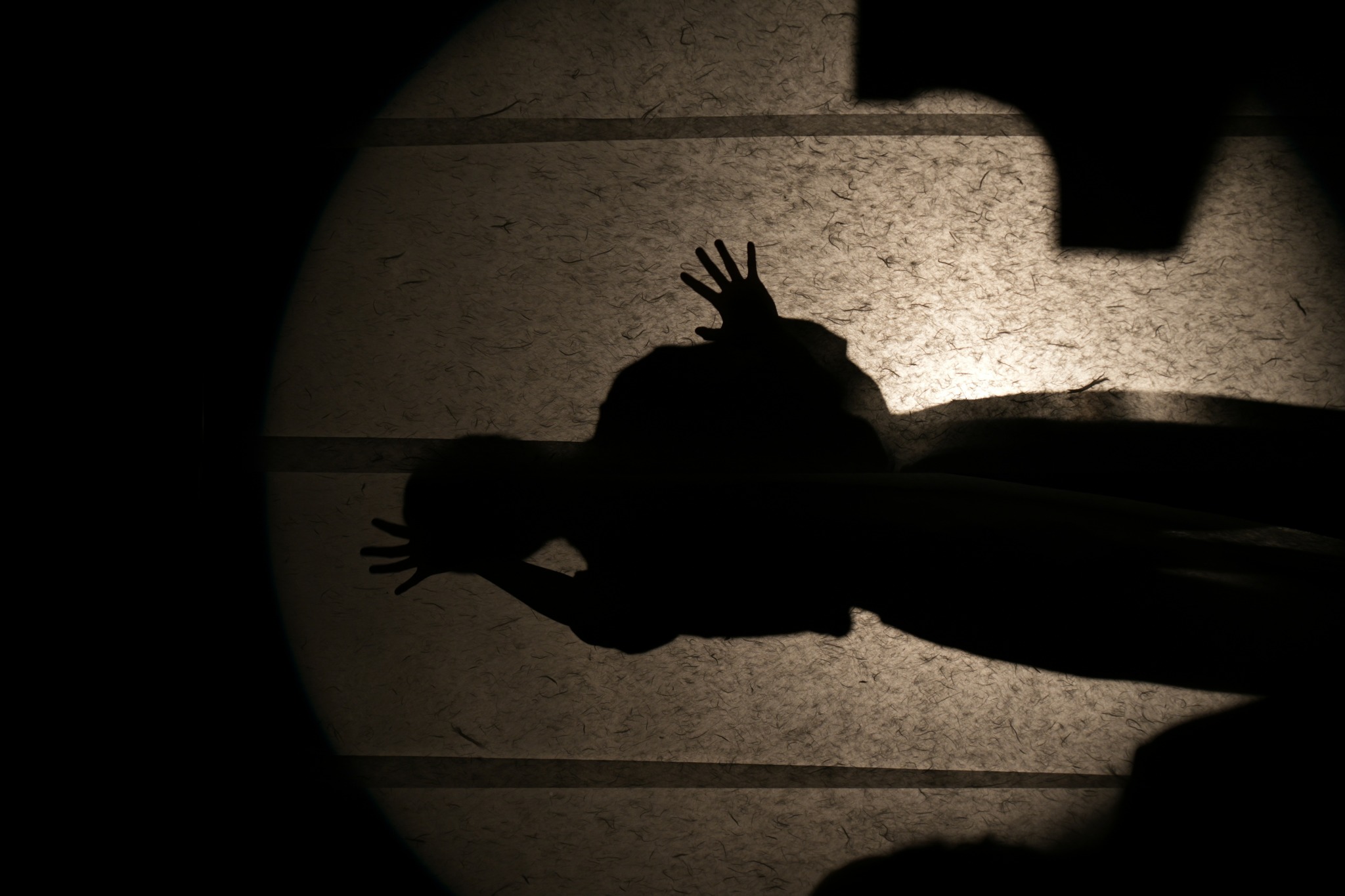

My main artistic interest is exploring subtle sound materials, like fragile sounds, resonance, small gestures, and the tiny changes that come out of repetition. Instead of creating perceivable pulses, I focus on subtle internal pulses within textures to generate tension and release. I am especially drawn to the sound qualities of objects and the tactile elements of sound itself, which I often turn into musical materials or even discover within the instrument. For instance, I recently incorporated traditional Korean paper, Hanji, in my work, 막/幕/veil, which was just premiered, using it as both a sound and visual material. I sampled the sound of Hanji for the electronics, which integrates seamlessly with the live performance, and I also used it as a screen to create a silhouette of the performer.

Beyond the sound itself, I am also interested in how physical gestures and kinesthetic senses, such as subtle muscle movements, performer’s breath, and pressure, which can have a very personal character, relate to the shaping and perception of sound. One of the most important topics in my music since 2022 is “How do we play, listen to, and perceive music?” The initial inspiration for this question came from a video of American sound artist Christine Sun Kim in Pop-Up Magazine (2020). She spoke about how closed captions often fail to convey what kind of music is actually playing in a movie or drama. Her words stayed with me for a long time and made me think deeply about sound and how it can be experienced. Her ideas also reminded me of the color field paintings of American artist Mark Rothko, where subtle textures and layers reveal themselves on closer inspection. Thinking about this, I started to question how I, as a composer, interact with the world through music and how I can share my ideas with audiences, including those who may not hear in a traditional sense. I began to ask myself: “What if I write music that can be heard without hearing, and seen without seeing?”

To explore this, I combine instrumental performance with electronics or material objects, sometimes with theatrical movements, to create multisensory connections between performer, sound, and listener. For example, in “Subtitles (alto saxophone, electronics, and visual media)” and “W-A-T-E-R (solo baroque cello)”, I explore minute gestures and kinesthetic interactions that shape the listening experience.

Outside composing, I also teach composition and music theory and work as an artistic director in two groups organizing concerts. I worked as an Associate Instructor at IU Jacobs School of Music from 2020 to 2023 and I currently give private composition lessons. Teaching is one of my favorite aspects of music. I enjoy supporting my students’ growth and learning from their unique ideas along the way. I have been getting so much support from numerous people on my way, and now I think it is my time to give those gifts I have received back to the students and become a teacher my students can always rely on musically and in their lives.

I also co-founded two music groups and have been organizing concerts based on what I have learned from seeing other people organizing their own events. In 2024, I co-founded a Korean women composers’ group called “ENAE” with my six fellow composers at IU. We aim to highlight Korean traditions through Western musical language, not simply to introduce Korean culture, but to communicate our own stories in a way that truly reaches the audience. Most recently, I co-founded a music festival, Overtuned Fest, with two of my good friends at IU, Alexey Logunov and Christopher Herz. This festival aims to blur boundaries between contemporary classical and experimental rock music, with a mission to dissolve barriers between musical worlds and audiences, which will happen in February 2026 in Bloomington, Indiana.

All my work requires collaboration and communication. I learn from performers during performances, guide students in teaching, and coordinate with others for projects and events. Through all of this, I hope to be seen not just as a composer who writes music, but as an open, warm, and engaged artist who embraces learning, collaboration, and connection in every aspect of my work.

Can you share a story from your journey that illustrates your resilience?

When the pandemic began in 2020, I had to move alone to Bloomington, Indiana, leaving behind my short but intense two years in New York. Everything shifted online, and nothing felt stable in this completely new environment. Beyond the personal challenges, I faced a musical one: my compositional style was very different from what I was encountering at school, and I found myself questioning which aspects of my music I should emphasize in order to grow and learn in this new context.

For more than a year, I wandered through this uncertainty, hesitant to change, and felt little artistic progress. Then, suddenly, I realized that what remained constant and sustaining was music itself, especially the works of composers I loved, like Béla Bartók, Richard Strauss, J.S. Bach, and Pyotr Tchaikovsky. Returning to these foundations, I began analyzing their music carefully and, at the same time, I approached new composers’ works in Bloomington with curiosity, viewing them as opportunities to experiment and discover elements I could integrate into my own personal sound. I transformed my fear of change into a period of active learning and experimentation, exploring a different style from what I had developed in New York, and using the challenges I faced as material for my music.

During this time, I also sought performance opportunities outside the school environment, despite the pandemic. I discovered that even in difficult circumstances, composers’ works were still in demand, and collaborations were possible. I became more active in seeking out projects and building connections.

This period ultimately strengthened my resilience. It allowed me to deepen my artistic voice, develop richer layers in my compositions, and approach both composition and directing with greater confidence. The experience showed me that challenges are not only obstacles, but also essential opportunities for growth and creative development.

For you, what’s the most rewarding aspect of being a creative?

For previous questions, my answers focused largely on how much of my work as a composer revolves around exploring sound, its textures, silences, resonance, and how these elements interact. However, I find that there are aspects of being a composer that are equally rewarding beyond simply creating music.

Of course, having my pieces premiered and performed again is deeply meaningful, but what I find most fulfilling is the process of collaborating with performers to bring a piece to life. Working together, making adjustments, supporting one another, and striving toward a shared musical vision have always been profound sources of learning and growth for me. Without them, my music would remain only on the page.

Another aspect I deeply value is the interaction with audiences. I have come to realize that how listeners experience a piece is not something I can or should fully control through program notes or explanations. Each person’s perception depends on their situation, thoughts, mood, and life experiences, just as it does for me. Sometimes high notes or fragile sounds might feel unsettling to someone, while low drone tones might resonate more deeply with another. The moments after a performance, when listeners share their impressions and interpretations with me, are especially meaningful. These exchanges give me insight, inspiration, and renewed motivation, reminding me why I continue to live as a composer.

Contact Info:

- Website: https://jeewonkimcomposer.com

- Instagram: @jen_nnnnny

- Youtube: https://www.youtube.com/@jeewonkim731

- Soundcloud: https://soundcloud.com/jen_nnnnny

Image Credits

Profile picture – Photo by Eric Tsai

Photo 3 (Silhouette on Hanji) – Photo by Longbow Image