We were lucky to catch up with Jari Bradley recently and have shared our conversation below.

Jari, thanks for taking the time to share your stories with us today Can you tell us about a time that your work has been misunderstood? Why do you think it happened and did any interesting insights emerge from the experience?

Rather than my work being misunderstood or mischaracterized, I find misunderstanding and mischaracterization as what fuels my work. Having lived long enough now to see a resurgence of the fatphobia, transphobia, and racial bias I’ve witnessed, and at times, experienced as an adolescent, my writing provides a front and center perspective from that of the perceived. As a fat Black transmasculine person writing in today’s time, a voice like mine is traditionally subdued and all out silenced, especially during a time where conservatism and fascism is on the rise nationally and abroad. The uniqueness of surviving within a world that so matter of factly anticipates your demise provides alternate possibilities that exist outside of the absolutes a history of colonial power, global genocide, and antiblackness almost certainly condemns us to. Writing poetry that documents and imagines this life through the eyes of someone who technically is not meant to exist reveals liberation as an aspect of the creative potential that lives in us to create other worlds. A potential creativity and commitment to freedom that pushes us to conceive of life outside or beyond the held perception of colonial, imperial, and capitalistic power that renders bodies/existences such as mine as errors or in need of correction. I am currently working on a suite of poems about Missy Elliott. The ability to discuss via poems the absolute genius and emancipatory imagination of Missy Elliott whose music videos and sound was like stepping into another dimension; and to mull over how my existence as a chubby Black tomboy growing up watching her express alternatives modes of Black existence encouraged me to define my own association to my body that was often being ridiculed or used for the satisfaction, humor, or gratification of others. To be able to speak to multiple oppressions using art and language as a vehicle for such makes poetry, and essentially all of the creative writing I do an avid practice of liberation while simultaneously existing as a someone who is not expected to exist or be heard from in any capacity. Poetry and creative writing makes the impossible possible, the unheard heard, and offers a plane for those of us with such rich imaginations our own platforms to display alternative possibilities of existence.

Awesome – so before we get into the rest of our questions, can you briefly introduce yourself to our readers.

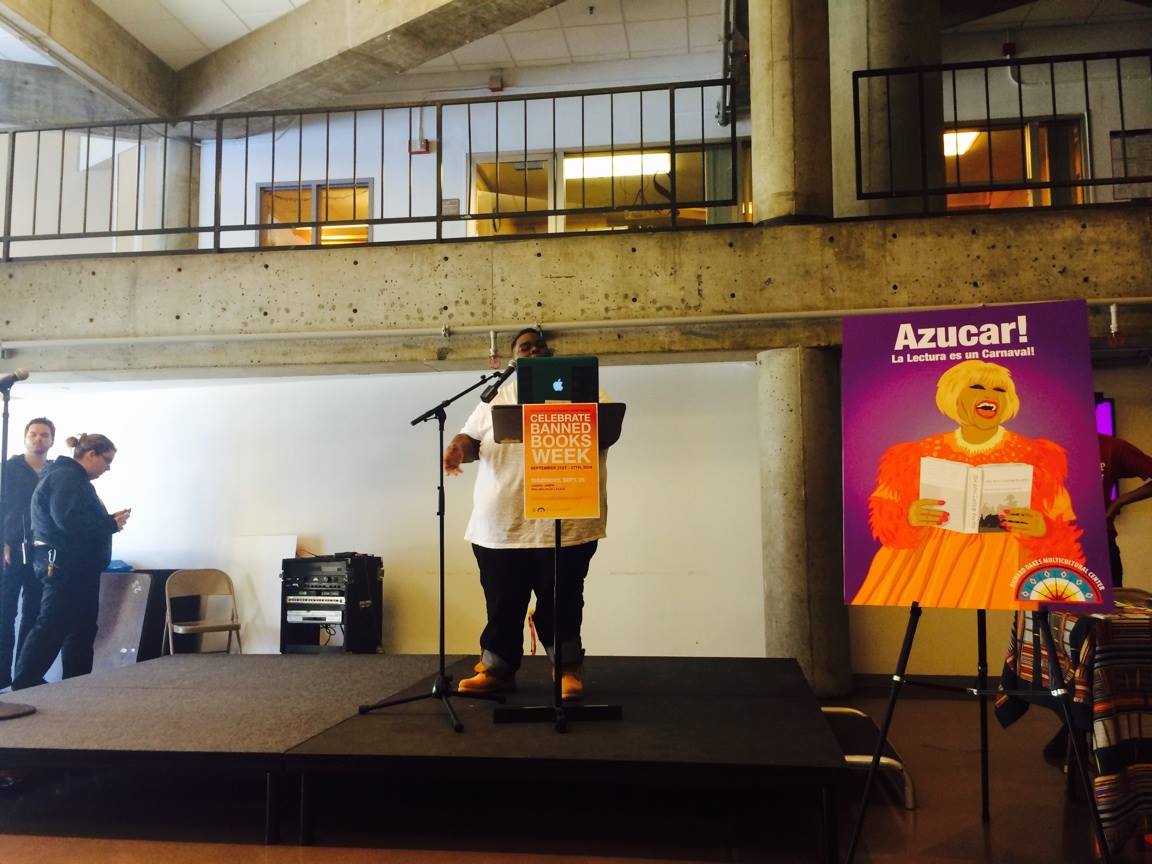

I’m a poet, writer, artist, and scholar from San Francisco, CA. I started out as a little veracious reader that would eventually find their way to slam poetry, and from there began to pursue creative writing professionally. I owe much of the writer I am to many of my first teachers: The Bay, my Grandmother, other intentional poets, displacement, and community oriented folk/teachers/organizers. I’m most proud of where and who I come from, all of the collective and individual circumstances that prepared me to be the writer I am, and the writer only I could be. When people think of poets they often think of lofty, well to do white men that dedicated themselves to self-expression. Poetry chose me, picked me up and gave me my name. It gave me something to do with the hypocrisy I was witnessing in the world, the language to detail cycles of abandonment, and also the voice to communicate an unceasing and enduring love for life in all its uncertainty. My work is for the misunderstood and mischaracterized. Those that recognize good music when they hear it. Essentially the work is for who it’s for, who can see something worthy within what’s there. I don’t know if my work as a poet is to solve problems as much as it is to expose them, drudge them up, and to create them. To constantly be a problem for a society that doesn’t mean for me to exist is crucial to my work. It’s a thing in my work to embrace the unruly in all its iterations as it relates to refusal and resistance. That there is power in being complicated and not easy to understand. That freedom exists there, that seeming unruly is a certain means by which folks seek to get free. Being the problem is key to being the solution within much of my writing.

What’s a lesson you had to unlearn and what’s the backstory?

When I was beginning to take myself seriously as a poet; and thinking I may want to do it professionally I had to unlearn a lot of messaging I’d picked up about what it meant to write good poetry. In some ways I was encouraged early in my youth to sensationalize certain aspects of my personal narrative. It took intentional poets from Black literary spaces like Callaloo and Cave Canem to teach me to trust my “I” in my poems. I had been warned that there were people who benefitted from me not centering myself in my work and that I deserved to hold that space despite often being discouraged from doing so. The historical trappings of lyrical poetry and certain schools of poetry make it clear that Black poets were not considered human, let alone poets capable of conveying the world they lived within. This is what makes Phillis Wheatley and Jupiter Hammon such important figures having been enslaved persons that persevered and thrived in the art of language at time that they could have been killed for it. When considering those two as historical ties I have to poetry, it bolsters the impetus of the work I do, which discusses the lived experience of someone who was never meant to speak on their own behalf. Following in such a tradition should enliven the national and global imagination around the emancipatory power of the perceived, persecuted for being seen as other, as stewards of a more examined and meaningful existence than the ones we are taught and encouraged to subscribe to. Writing for these individuals meant placing their lived experiences at the core of the work and enlightening the world as people once purchased like that of cattle or livestock. That humanity was ultimately denied these individuals despite their literary and written prowess that only enhanced our notions of what it meant and means to be alive.

Is there a particular goal or mission driving your creative journey?

I believe what’s driving my creative journey is an insistence on writing that comes from a greater will to live. And not just to be alive but to live a life of my choosing. Which in retrospect may seem a bit oxymoronic considering my belief that poetry chose me. But in the end I think I’ve always been someone who walked to their own beat, and all I’ve ever wanted has been to be seen as someone living authentically and creatively for the betterment of the world around them. To take misunderstanding and mischaracterization and utilize each to address the potent and profound silences many of us live with daily. I am encouraged to encourage others to try and live as authentically as one can dare as to do so is despised. So many in this country and in the world are afraid of their own selves, and would rather inflict rules or legislation that condemns the lived realities of many of us unafraid to live out loud. Those of us unapologetic in our living. I believe part of my work is to stir the pot; to upend the table in the temple as to convey that too much is at stake to live inauthentically. We can dispel a lot of misery by simply embracing all aspects of who we are are as individuals and collectively as a society of people so scared of being the truest, contradictory versions of themselves. Poetry continues to assist me in being braver version of myself. Once when I was younger, a relative of mine said that one day I would wake up and realize that the writing I was doing was just a hobby, and that I’d have to go on and find more serious pursuits. Thankfully that relative was completely wrong and that I’ve been able to write myself into opportunities that have grown me beyond measure. Beyond anything that relative or I could imagine. And that doesn’t mean that the writing has to be perfect, just that it has to be consistent. Something you strive to get better at each attempt. On this journey I’ve not only had to strive for that consistency, but I’ve also had to protect my writing practice from people who couldn’t understand my impulse to do so.

Contact Info:

- Website: https://jaribradley.com

- Instagram: sojari

- Twitter: @jab_poet