We caught up with the brilliant and insightful Janice Merendino a few weeks ago and have shared our conversation below.

Alright, Janice thanks for taking the time to share your stories and insights with us today. Can you tell us about a time that your work has been misunderstood? Why do you think it happened and did any interesting insights emerge from the experience?

I gravitated toward art at a very early age. It wasn’t that I thought I had any natural ability, it was just that I was very shy as a child. So, making things was a perfect way for me to “hide” around people and limit my interactions. As I got older, sharing my passion for the arts must have overpowered my insecurities. I find it funny that I chose a career in teaching where shyness isn’t really an asset.

So, your question about a time when I was either misunderstood or mischaracterized resonates with me. It wasn’t that I was mischaracterized as an artist, rather, I believe that I characterized and labeled myself as an artist too narrowly and too early.

My kindergarten teacher told my mother that I was going to be an artist because I drew my turtles different from everyone else. It seems silly now, but when I heard that my turtles were “good”, I took it to heart and looked for more opportunities to get that affirmation by drawing and painting. Seeing that I wasn’t getting similar praise or encouragement in other areas, I decided as a child that I probably wasn’t very good at anything else. Sometimes I feel that I built my life on the very thin evidence of my so-called “talent” for drawing turtles!

Looking back, I now see that labeling and praising talent can be a disservice, blinding us from what else may be there. “I’m an artist” became my excuse for my weakness in math or missing the ball in gym class.

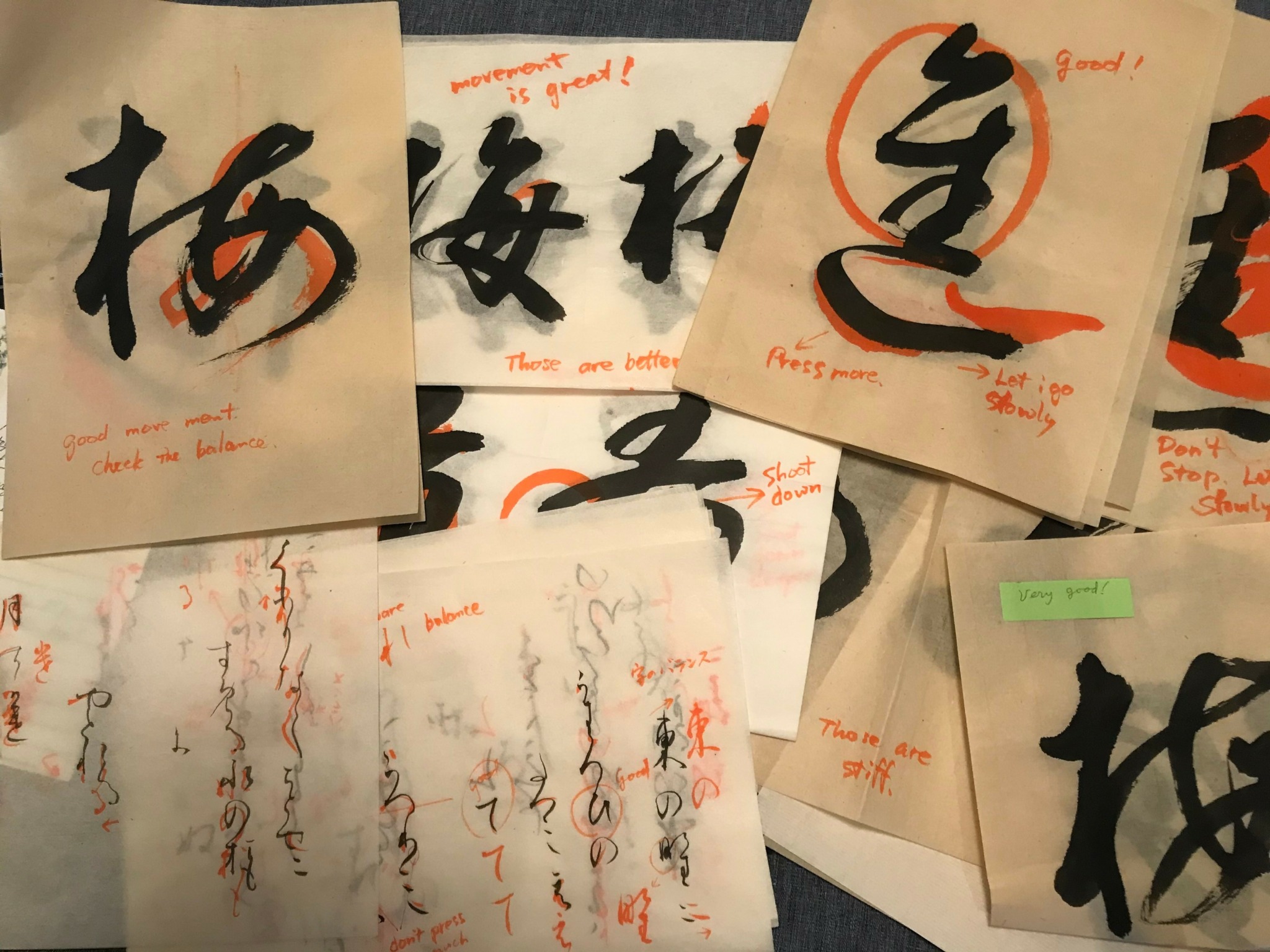

Often, what people mischaracterize as talent is really the progress that comes from doing something regularly that you commit to and enjoy. Generally, I found that people don’t acknowledge the artist’s hours of disciplined effort, especially when they see only the finished work. It’s easier to think “I could never do that; they are so talented and I’m not.” In my teaching I find that people wear these negative labels as a badge and use it as an excuse not to try.

As always, we appreciate you sharing your insights and we’ve got a few more questions for you, but before we get to all of that can you take a minute to introduce yourself and give our readers some of your back background and context?

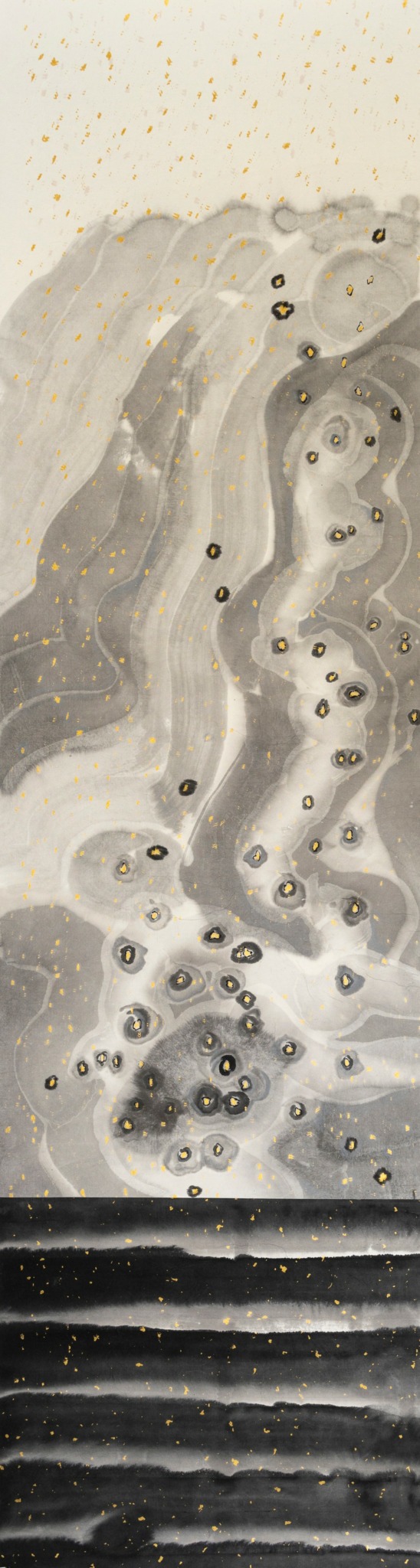

My first love in art college was working in clay. As a student, I did an independent study in Japan to study ceramics and visited four ancient kiln sites, which sparked a lifelong love of the country and its culture. I was lucky enough to be able to visit and study there five more times. In Japan, I also developed a passion for calligraphy and traditional Japanese papers which I later incorporated into my paintings and ceramic work.

I was one of five founders of The Clay Studio in Philadelphia in 1974, the same year I graduated from Moore College of Art and Design. The Clay Studio has blossomed from our humble beginnings into a wonderful cultural asset for Philadelphia and the field of ceramics.

Right out of college, I was fortunate enough to get a job teaching art, even before I had an established career as an exhibiting artist. It was the perfect first job where I was given free rein to develop curriculum and try a wide variety of projects in different media with my high school and middle school students.

In 1980, I was hired as a professor of Fine Arts at Rosemont College. I taught there for 36 years designing undergraduate art courses and later two graduate level courses in Visual Literacy for the MFA program. In one course, “Artful Writing: using other art forms to enhance your writing”, I introduced drawing, music, movement and other art forms to the creative writing students. They worked on their writing individually with experts in each art form. My goal was to have them experience first-hand how their writing overlaps with other art forms.

From 1998 through 2023, I designed and taught workshops at the Philadelphia Museum of Art for groups with cognitive and physical disabilities, working extensively with people with Parkinson’s disease and Veterans with PTSD.

Also in 1998, I began The Branch Out Project offering arts-based visual literacy workshops to business executives and others. The primary focus was to teach non-artists how to draw and then show them how they can transfer those visual problem-solving skills to other areas of work and home life. When executives and other accomplished adults say to me that they can’t draw, I tell them that I think they are smart enough to learn. This remark catches them by surprise.

In the performing arts, we seem to better understand that if we were handed a violin, we wouldn’t be able to play it unless we had qualified teachers and extensive practice over a long period. But in the visual arts we expect ability to emerge spontaneously as if by magic. This lack of self-awareness has larger ramifications. The labels we put on ourselves and others actively keep us from making progress at solving some important problems. Most problem situations benefit from a cross disciplinary approach. This means that the more people question their self-imposed limitations, open themselves up to assistance from others and go into places they don’t think they belong, the more we all can bring to the table.

Is there mission driving your creative journey?

Since active participation in the visual arts is outside of the comfort zone of many, my goal in my teaching has been to develop approaches that are accessible to a wide audience. I enjoy rethinking advanced techniques in the art making process and creating activities for beginners to think deeply about what they see around them.

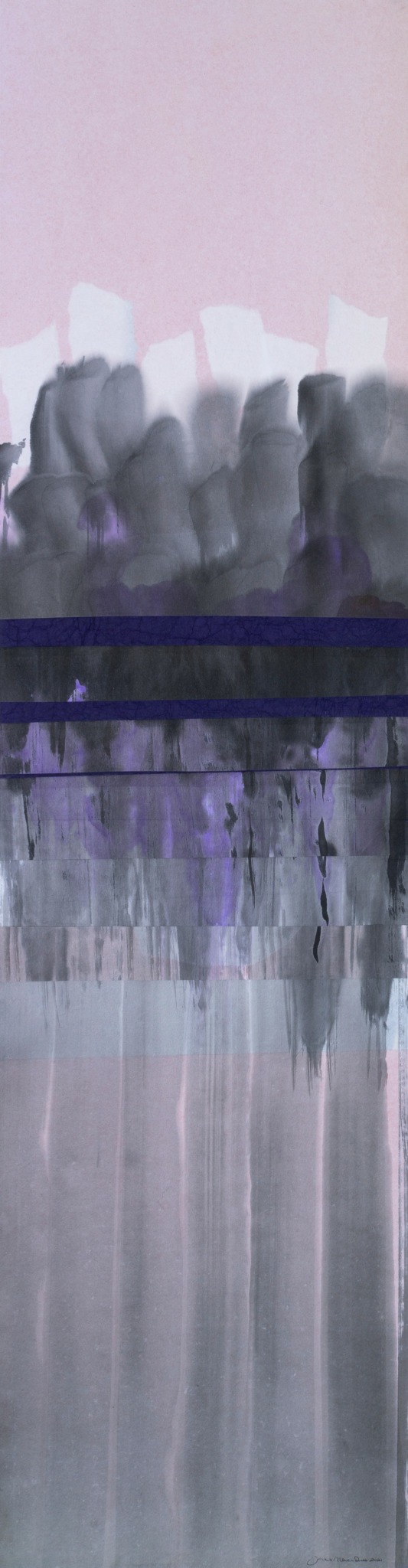

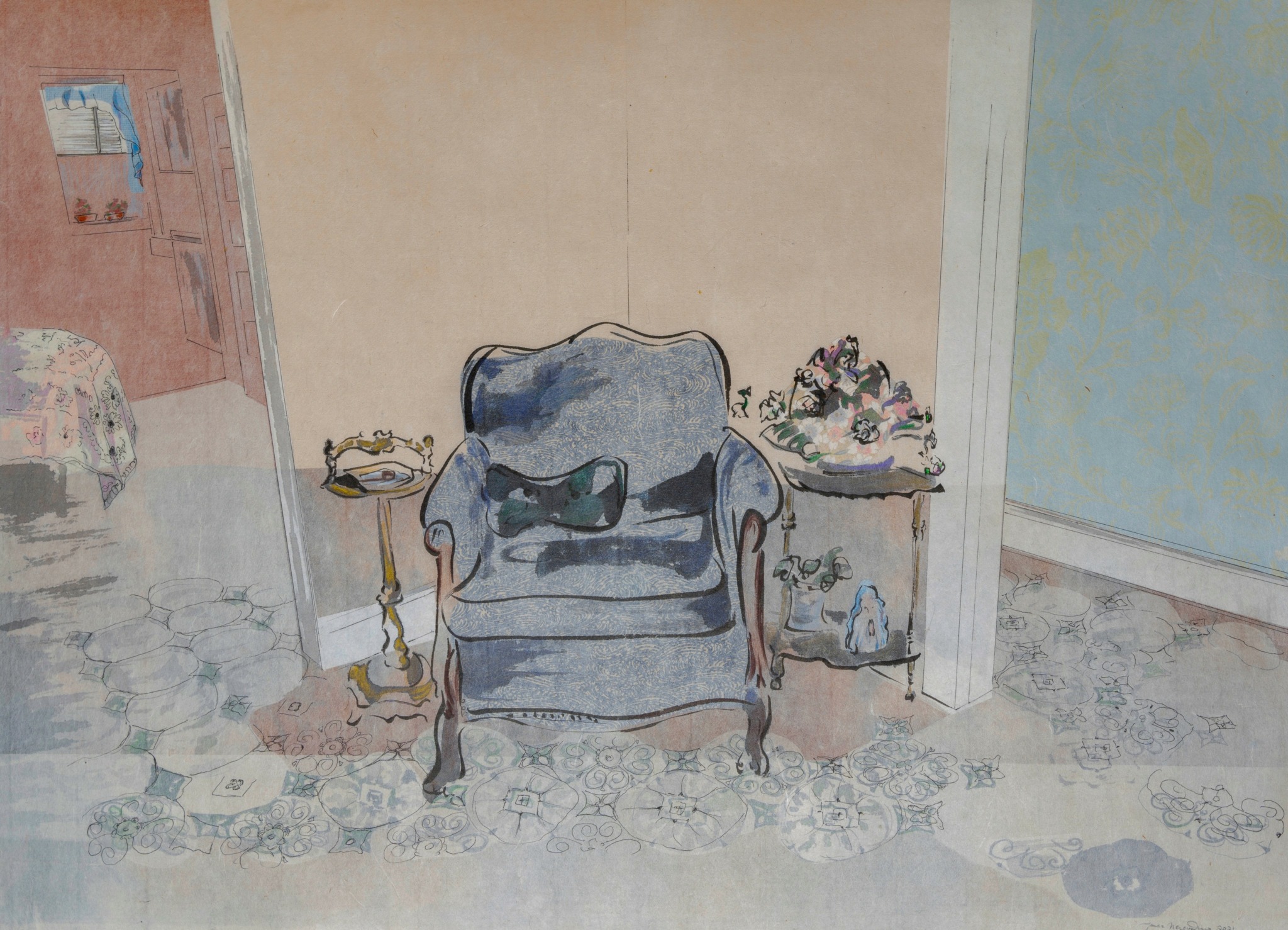

In my art practice, the challenge is how to communicate who I am and what I value. This has meant exploring as many aspects of myself as I can through my work. Sometimes my studio is a place of calm refuge and other times it’s a scary place where I confront my fears and regrets.

In the work itself, I switch mediums, move back and forth between abstract work and figurative work, try new techniques and welcome collaborations in other kinds of projects. The exhibited work often includes a narrative and explanations that hopefully invite people toward a conversation.

Are there any resources you wish you knew about earlier in your creative journey?

Early in my career, I didn’t take advantage of the wide range of activities Philadelphia’s many universities, museums and cultural institutions offered. I rarely ventured into lectures about science, anthropology, history, business and other subjects that could have given me a more robust and well-rounded education.

I’m trying to make up for that now by developing interests and skills outside of visual art like studying classical guitar. As someone with very little musical background, the guitar helps me to empathize with people in my drawing workshops who say, “I could never do that!” Watching yourself as a beginner is humbling and exhilarating, teaching you to navigate roadblocks and keep yourself motivated in the face of failure.

Contact Info:

- Website: https://janicemerendino.com

- Instagram: janicemerendino

- Youtube: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GyVlIAqIrtA https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XrTSy6dg5LU

- The Branch Out Project: https://www.branchoutproject.com

Image Credits

Don Wilson