We recently connected with Harry Tkalenko and have shared our conversation below.

Harry , thanks for joining us, excited to have you contributing your stories and insights. Let’s start with a story that highlights an important way in which your brand diverges from the industry standard.

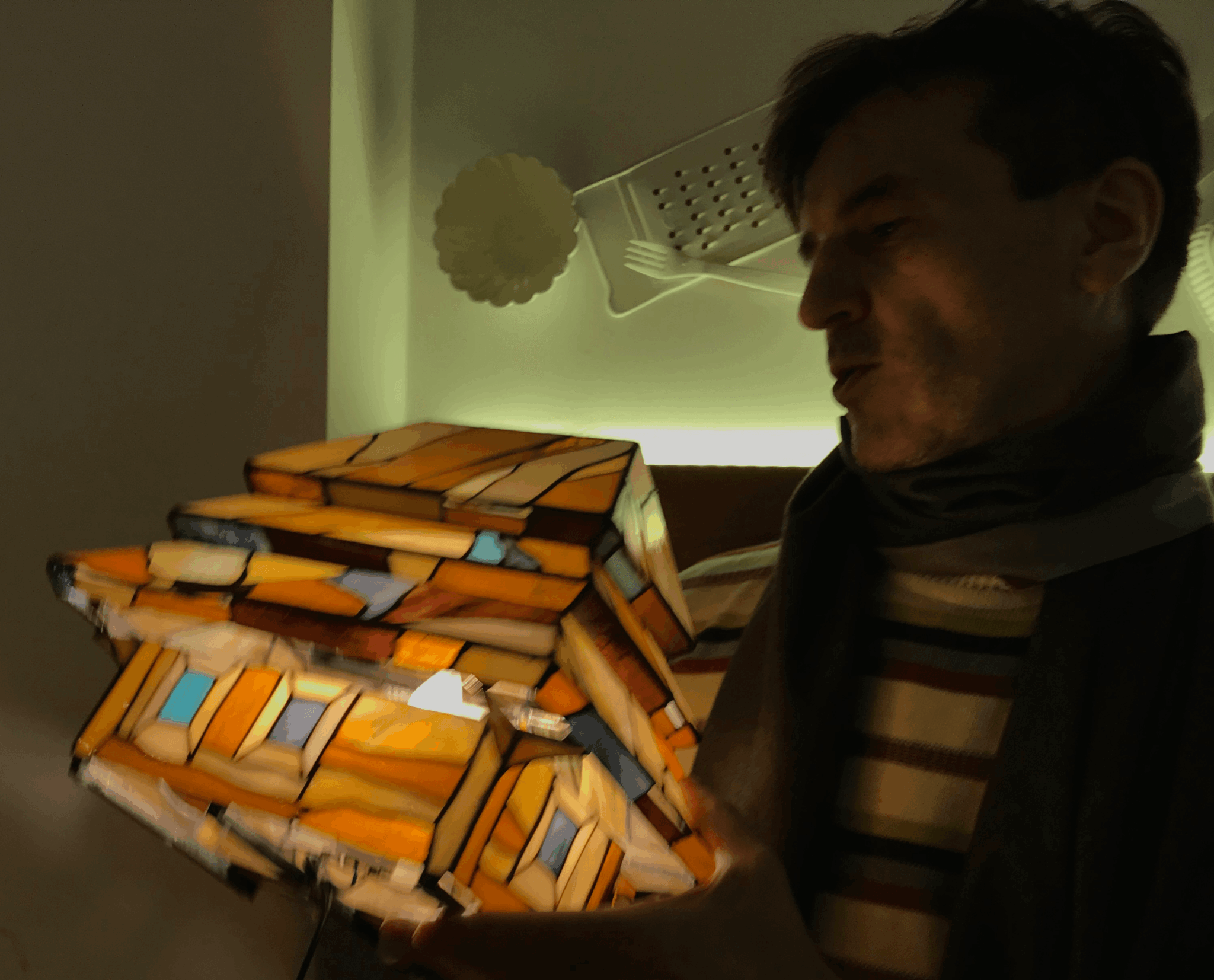

Ostap Pavlovsky—a Lviv architect who designed the Lviv-Arena stadium, UCU (Ukrainian Catholic University), the Arsen supermarket… and many other objects in Lviv. These stained-glass lamps were his hobby. He made them as gifts for friends and family… Then people started ordering them. That’s how this unique art form was born—replicas of houses made of stained glass. Today, in Lviv, there’s the Pavlovsky Lamp Studio, where five craftsmen create stained-glass house lamps based on the Maestro’s designs and unique technology.”

“So, this is stained glass?”

“It needs some explanation. Do you have ten minutes?”

“Well, sure, I guess…” I replied, not yet realizing this conversation would stretch far beyond ten minutes.

“So… there are two main stained-glass techniques. (There are actually many, but to keep it simple, I’ll just tell you about two.) In classic stained glass, colored glass pieces are joined with an H-shaped lead profile. That kind of stained glass can only be vertical and flat, or 2D. You’ve seen it in churches—it’s a very ancient technique. Classic stained glass isn’t rigid like a windowpane—it’s a ‘living’ structure. If you push it, it might ‘flow’ or ‘bulge’… That’s why in tall windows, it needs extra reinforcement for stability. In the early 20th century, American artist Louis Comfort Tiffany started making three-dimensional stained-glass lampshades. That’s how the famous Tiffany lamps and the technique of volumetric stained glass, now called the Tiffany technique, came to be. Today, all small stained-glass lamps are called ‘Tiffany,’ though Tiffany himself only patented the method of assembling shades on a form (a dome)…

Maestro Pavlovsky made his stained-glass houses without any forms, domes, or models. He built them like a builder—from the foundation to the roof vault. That’s the Pavlovsky technique, which he passed down to our craftsmen. He also used little tricks, like shards of Italian crystal in the windows or balconies and cornices made of unwrapped glass inserted perpendicular to the stained-glass plane. See how those pieces glow brighter than the others? Those are Maestro Pavlovsky’s light minicolliders. They accelerate light, concentrating photons at the edges…”

The story about Pavlovsky creating light accelerators sounded like nonsense, but I could see with my own eyes that the colored glass pieces inserted perpendicular to the stained-glass plane glowed brighter…

Meanwhile, impresario Hari continued his strange tale. At least now I understood how classic stained glass differed from Tiffany.

“Some people think the Tiffany technique is just joining glass with copper foil soldered with tin. Tiffany used that method, but he didn’t invent it. Today, all small stained-glass pieces are made this way: each glass piece is wrapped in thin copper tape that hugs the glass and slips into its crevices. When that copper strip is soldered with tin, it forms a rigid frame, allowing the pieces to be joined at angles and create three-dimensional stained-glass objects. By the way, Tiffany was recognized as a great New Yorker in his lifetime. The Metropolitan Museum gave his stained glass an entire wing. In Lviv, everyone considered Pavlovsky, to put it mildly, a weirdo… And now we’re thinking: maybe he was a genius after all, because he created something that didn’t exist before…”

“And why did they think he was a weirdo?” I asked.

“Well, to give you an idea… A client comes—an old customer who’d already ordered houses from Ostap—and asks him to make this palace, which we called the Pshonka house. He came back six months later and gave a deposit. The client was expecting a price of 2–3 thousand dollars and, knowing Maestro’s leisurely nature, asked him to finish by October 3rd, as it was a gift for a client’s anniversary and housewarming for that palace. There were almost five months to do it, and Maestro decided to experiment with bent glass. Meanwhile, he caught some kind of COVID again. But for a couple of months, he went to a friend who had a professional kiln and bent glass pieces there to make the rounded elements look as beautiful as you see them now.

The stained-glass craftsman helping him with the house gradually received parts of the blueprint and the bent glass pieces from Ostap, and a month before the deadline, he’d built the house’s walls. All that was left was the roof. When the craftsman cut the glass for the roof and started soldering it, it turned out that either Maestro had miscalculated or the craftsman had altered the house’s dimensions during the process… In short, the roof didn’t fit. If it had been assembled on a model using the Tiffany technique, the mistake could’ve been fixed easily, but for Maestro, an architect, making models was beneath him. Pavlovsky drew blueprints, calculating the shape and size of each glass piece in advance. So, when all the glass was already cut, a small error meant the roof vault didn’t align, and the entire cut roof had to be thrown out. Maestro blamed the craftsman; the craftsman said, ‘Take it away, I’m not doing it, finish it yourself…’ And Pavlovsky took it on himself. By October 3rd, there was neither a house nor Maestro Pavlovsky. When they finally found Ostap a few days later in a pub on Chuprynky Street, he asked:

“Listen, are you idiots? Why are you so hung up on October 3rd? Give it a month later, and it’ll be a masterpiece!”

“No, Ostap, you’re the idiot if you don’t get that the gift was needed on the 3rd, and on the 4th, it’s useless!”

“These simple folks rarely dealt with geniuses, so they called Maestro Pavlovsky’s behavior pigheaded… Now I realize he just lived in the realm of eternity. He didn’t churn out junk or create for money. Most of his masterpieces he gave away practically for free, often not even covering the cost of materials… That’s why the Maestro Pavlovsky Lamp Studio, which we founded with Ostap, went bankrupt several times. You could say it was in a state of permanent bankruptcy. The Pshonka palace, which was supposed to be done by October 3rd, we finished in July of the next year, after Ostap’s death. And since none of the craftsmen wanted to touch it, I had to order a cardboard roof model from another craftsman and then assemble it in glass on that form using the Tiffany technique.

When I told the client how much this house cost us, he said, ‘Give me my money back, it’s not relevant anymore.’ Now I don’t know how much this last Pavlovsky house might be worth. Original Tiffany lamps sell at Sotheby’s today for 1.5 million dollars. This lamp might be worth no less in a hundred years…”

I listened to Hari’s story, and before my eyes unfolded an unknown, mesmerizing world of stained-glass lamps. As a budding art historian, I felt like a gold prospector who’d just stumbled onto a vein.

“You’ve noticed that you can look at stained-glass houses endlessly—they don’t get old. It’s a kind of light therapy,” Hari said enthusiastically, pouring out everything he knew, every dusty story he could dig up from the corners of his memory, thrilled to finally find someone to listen. “As I mentioned, Pavlovsky’s houses are unique because the technique of these lamps rests on the core principles of architecture.”

“What do you mean?”

“The foundations of architecture? You see, Ostap Pavlovsky was first and foremost an architect, so when building his ‘lamps,’ he followed the three principles laid out by Vitruvius, the legendary Roman architect: utility, strength, and beauty. If a structure is strong but not beautiful, it’s not architecture. If it’s beautiful but not sturdy, it’s not architecture—it’ll collapse and kill people. (By the way, the word ‘architect’ comes from Greek and means ‘builder.’) When it comes to architectural stained-glass lamps, you can’t forget that it’s a table lamp, meaning it’ll be moved around, so Pavlovsky designed the house’s structure to be easy to pick up and carry with one hand. If a building or part of it isn’t useful—then why bother? The balconies in Maestro Pavlovsky’s lamp-houses are meant for storing jewelry. As for beauty, it’s not just about picking the colors of the stained glass. It’s the shape of the houses themselves, as if they’ve just stepped off Lviv’s streets—unexpected extensions, towers, courtyards, buttresses, flying buttresses, chimneys, drainpipes, terraces and loggias, cornices, gables, pediments, and bay windows—all these elements make Pavlovsky’s houses feel alive. No wonder he depicted Lviv as a cheerful crowd of houses with legs and mustaches, strolling arm-in-arm, singing a batyar song. By the way, Maestro Pavlovsky could draw any Lviv building from memory…”

“And how did the idea of creating Pavlovsky’s lamps even come about? Was it his hobby since university?” I asked, hoping to get an answer to the evening’s main question.

“No… Actually, Ostap Pavlovsky-Lisohorsky (his full name) built a career purely as an architect after university, and his signature lamps were still far off. For example, one of his projects as an architect was the Arsen supermarket. But Pavlovsky had much grander plans for the supermarket than his client did. It got to the point where the client complained about the project’s high cost:

‘Simplify it.’

Pavlovsky told me:

‘I designed Arse-e-e-e-e-n!!!! And you’ve turned me into a lamp-maker! Am I some souvenir peddler to you?!’

He thought making stained-glass lamps for money was beneath an architect. He made them as gifts for friends, but it was just a hobby.”

Great, appreciate you sharing that with us. Before we ask you to share more of your insights, can you take a moment to introduce yourself and how you got to where you are today to our readers.

For those who haven’t yet stumbled upon us, we are the Architect Pavlovsky Lamp Studio, a unique creative endeavor rooted in the heart of Lviv, Ukraine. Our story is one of passion, artistry, and a touch of architectural genius, sparked by the late Ostap Pavlovsky—a visionary architect whose legacy we carry forward. Allow us to share how we came to be, what we create, the problems we solve, what sets us apart, and what we’re most proud of.

How We Got Here

Our journey began with Ostap Pavlovsky, a Lviv architect renowned for designing landmarks like the Lviv-Arena stadium and the Ukrainian Catholic University (UCU). But beyond his professional achievements, Ostap had a private passion: crafting stained-glass lamps that replicated the charm of Lviv’s historic buildings. What started as a hobby—making these glowing miniature houses as gifts for friends and family—evolved into something extraordinary. Inspired by his architectural expertise and a love for stained glass, Ostap developed a technique to transform two-dimensional stained glass into three-dimensional, functional art pieces without molds or templates, building each lamp like a real house, from foundation to roof.

After Ostap’s untimely passing in 2023, his friend and impresario, Hari, along with a dedicated team of five craftsmen, founded the Pavlovsky Lamp Studio to preserve and expand his legacy. We entered the niche industry of artisanal lighting and decorative art, blending architecture, stained glass, and storytelling to create lamps that are more than just objects—they’re pieces of Lviv’s soul. Our craft emerged from Ostap’s refusal to compromise on quality or vision, even when it meant working against deadlines or financial pressures. His story, detailed on our website (budynochky.com), is one of resilience, creativity, and a relentless pursuit of beauty.

What We Create

At the Architect Pavlovsky Lamp Studio, we produce unique stained-glass lamps designed as miniature replicas of houses, inspired by Lviv’s eclectic architecture—think neo-Gothic villas, medieval facades, and whimsical townhouses. Each lamp is a functional work of art, handcrafted using Ostap’s proprietary technique, which sets it apart from traditional stained-glass methods like Tiffany or classic church-style designs. Our lamps feature:

• Architectural Precision: Built with the principles of Vitruvius—utility, strength, and beauty—our lamps are sturdy enough to be moved with one hand, with details like balconies for storing jewelry.

• Innovative Techniques: We use Italian crystal shards for windows, perpendicular glass for “light minicolliders” that amplify glow, and bent glass for organic curves, all without molds.

• Custom Designs: From replicas of real buildings (like the Alfa Bank on Rynok Square) to allegorical pieces like the neo-Gothic “Brugge Tavern,” we tailor lamps to client visions or create original designs.

Our services extend beyond production. We offer custom orders, consultations for bespoke designs, and exhibitions in our Lviv gallery (as noted on our Facebook page,). We also maintain a “memory space” in a Lviv basement, where visitors can explore Ostap’s works and learn about his creative process.

Problems We Solve for Our Clients

Our clients—art collectors, interior designers, gift-givers, and Lviv enthusiasts—come to us for solutions that go beyond ordinary lighting. We address several key needs:

• Unique Gifting: Our lamps are one-of-a-kind gifts that carry emotional weight, perfect for anniversaries, housewarmings, or corporate VIP presents. For example, clients have commissioned replicas of meaningful buildings, solving the challenge of finding a personal yet luxurious gift.

• Interior Design Elevation: Designers use our lamps to add a focal point to spaces, blending functionality with art. The glowing houses create ambiance and tell a story, solving the problem of generic decor.

• Cultural Connection: For those tied to Lviv or Ukrainian heritage, our lamps preserve and celebrate the city’s architectural spirit, offering a tangible link to home or history.

• Emotional Resonance: As Hari notes on budynochky.com, our lamps provide “light therapy”—their warm glow and intricate details captivate viewers, offering a meditative escape from daily stress.

Unlike mass-produced lighting, our lamps solve the problem of soulless decor by delivering handcrafted, narrative-driven pieces that feel alive, as if they’ve “stepped off Lviv’s streets.”

What Sets Us Apart

What makes us unique? It’s a blend of heritage, technique, and philosophy:

• Ostap’s Technique: Unlike Tiffany lamps, which rely on dome molds, or classic stained glass, which is flat, our lamps are built freeform, like miniature buildings. This proprietary method, using perpendicular glass and crystal accents, creates a brighter, more dynamic glow (budynochky.com).

• Architectural Roots: Every lamp adheres to architectural principles—utility (functional design), strength (durable construction), and beauty (aesthetic harmony). This grounding in Vitruvius’s triad sets us apart from purely decorative stained-glass art.

• Lviv’s Spirit: Our designs capture Lviv’s eclectic charm—towers, courtyards, and batyar songs woven into glass. No other studio so vividly translates a city’s identity into light.

• Storytelling: Each lamp tells a story, whether it’s the tragic creation of the Pshonka palace or the whimsical “fairy houses” of Ostap’s early experiments. This narrative depth, shared on our website, resonates with clients seeking meaning in their purchases.

Our small-scale, artisanal approach—only five craftsmen, working from a home studio—ensures exclusivity. Unlike large manufacturers, we prioritize quality over quantity, often at the cost of financial stability, as Hari candidly admits on budynochky.com.

What We’re Most Proud Of

We’re proud of several milestones, each tied to Ostap’s legacy and our ongoing work:

• Preserving Ostap’s Vision: After his death, we kept his technique alive, training craftsmen to replicate his exacting standards. The studio’s survival, despite “permanent bankruptcy,” is a testament to our commitment.

• Iconic Creations: The “Brugge Tavern,” a neo-Gothic masterpiece, is a fan favorite, with Lviv residents claiming to recognize it on various streets—a sign of its authentic spirit (budynochky.com).

• Cultural Impact: Our lamps have become symbols of Lviv’s resilience, especially post-2023, as we’ve exhibited them in galleries and shared Ostap’s story globally via platforms like Facebook ().

• Client Stories: We cherish moments like delivering a custom lamp for a client’s anniversary, knowing it became a family heirloom. These personal connections fuel our pride.

What We Want You to Know

To potential clients, followers, and fans, here’s the heart of who we are:

• We’re Artisans, Not Manufacturers: Every lamp is a labor of love, made with the same care Ostap poured into his designs. Expect perfection, not speed.

• We’re Storytellers: Buying a Pavlovsky lamp means owning a piece of Lviv’s history and Ostap’s legacy—a story you can share with every glow.

• We’re Exclusive: With only a handful of lamps produced yearly, you’re investing in rarity. Our website (budynochky.com) showcases our portfolio, but custom orders are our specialty.

• We’re Human: Like Ostap, we’ve faced setbacks—bankruptcies, missed deadlines, personal losses. But we persist because we believe in beauty and meaning.

We invite you to visit our Lviv gallery, explore budynochky.com, or follow us on Facebook (Architect Pavlovsky Lamps Studio) to see our latest creations. Whether you’re seeking a statement piece, a meaningful gift, or a connection to Lviv’s magic, we’re here to light up your world—literally.

With warmth,

The Architect Pavlovsky Lamp Studio Team

Lviv, Ukraine

Have you ever had to pivot?

A Time I Had to Pivot: From Publishing to Preserving a Legacy

In life and business, there are moments when you’re cruising along, thinking you’ve got it all figured out, and then—bam—something forces you to slam on the brakes and take a sharp turn. For me, that pivot came when I transitioned from being a publishing director to becoming the impresario of the Architect Pavlovsky Lamp Studio, a move that wasn’t just a career shift but a leap into preserving a friend’s legacy and breathing life into a unique art form.

Back in the mid-2000s, I was running a publishing house in Kyiv, Ukraine. But then I stumbled across something extraordinary: the stained-glass house lamps of Ostap Pavlovsky, a brilliant architect and my old classmate. These weren’t just lamps; they were miniature replicas of Lviv’s buildings, glowing with the soul of the city, crafted with a technique Ostap had invented himself. I was hooked. I started ordering these “Pavlovsky houses” as New Year’s gifts for my publishing clients—about 30 to 40 a year. They were a hit, a perfect blend of art and sentiment that made every recipient feel special.

Things were going smoothly until Ostap hit a rough patch. He split with his girlfriend, Roksolana, a skilled stained-glass artist who’d been helping him make the lamps. Without her, Ostap stopped producing them. For a while, I tried ordering from Roksolana directly, but it wasn’t the same. Her work was technically fine, but it lacked Ostap’s spark—the architectural precision, the quirky details, the life he poured into each piece. I realized that without Ostap, these houses were just pretty objects, not the storytelling masterpieces I’d come to love. That was my first wake-up call: I couldn’t just be a middleman anymore. If I wanted these lamps to live on, I had to do something bigger.

I started nudging Ostap to take his craft seriously, to turn his hobby into a proper venture. “Let’s start a studio,” I’d say, half-joking, half-pleading. He wasn’t convinced—Ostap was an architect, not a “souvenir peddler,” as he’d grumble. But then life threw him a curveball that changed everything. Ostap suffered a severe head injury, a traumatic event that required surgery and left him unable to work his regular architectural job. He was stuck at home, grappling with recovery and a foggy future. It was a low point, but it was also the moment when he finally said yes to the idea of a studio. That was our pivot—Ostap’s from architect to full-time lamp craftsman, and mine from publisher to the guy who’d make sure his vision didn’t die.

We dove in, founding the Architect Pavlovsky Lamp Studio. I took on the role of impresario, handling orders and pricing, while Ostap focused on creating. We hired two talented stained-glass artists, both named Olia, forming what Ostap jokingly called our “Oliobih” (Olia-cycle). The early days were chaotic but exhilarating. New projects poured in—first weekly, then daily. We designed new house models, each one more intricate than the last, from neo-Gothic villas to whimsical “fairy houses.” Clients, from art collectors to corporate gift-givers, were captivated by the lamps’ glow and the stories they told, like the “Brugge Tavern,” a fan favorite that seemed to step right off Lviv’s streets (budynochky.com).

This pivot wasn’t just about starting a business; it was about giving Ostap a purpose during his darkest days and preserving his unique art form. It wasn’t easy—financial struggles, missed deadlines, and Ostap’s uncompromising perfectionism led to what we called “permanent bankruptcy.” But every new lamp, every client’s smile, made it worth it. I’m proudest of the moment we turned Ostap’s recovery into a creative renaissance, building a studio that’s now a beacon of Lviv’s cultural spirit.

For anyone considering working with us, know this: we’re not just selling lamps. We’re offering a piece of Lviv’s heart, crafted with architectural rigor and emotional depth. Our studio, detailed on budynochky.com, is a testament to resilience—Ostap’s, mine, and our team’s. If you’re looking for art that tells a story, solves the problem of soulless decor, or simply lights up your life, we’re here, ready to create something extraordinary.

Let’s talk about resilience next – do you have a story you can share with us?

Ostap was a perfectionist. Every lamp had to be flawless, built from scratch using his proprietary method—no molds, just his blueprints, Italian crystal shards, and “light minicolliders” that made the glass glow brighter (budynochky.com). But his relentless pursuit of quality meant he couldn’t keep up. Deadlines were slipping, clients were getting antsy, and I could see the strain in Ostap’s eyes. He was burning out, and the studio was at risk of stalling just as it was gaining momentum. I remember sitting in our cramped basement workshop, surrounded by half-finished lamps, thinking, “If we don’t fix this, Ostap’s legacy is going to flicker out.”

That’s when I knew I had to act. I couldn’t let the studio—or Ostap’s vision—collapse under the weight of its own success. So, I started making calls, reaching out to every stained-glass artist, craftsman, and friend I could think of. I was practically begging, “Can you make Pavlovsky lamps? We’ve got Ostap’s blueprints, his exact technique—can you help us keep this going?” It wasn’t easy. Some laughed, saying it was impossible to replicate Ostap’s work. Others were skeptical, unsure if they could match his obsessive attention to detail. But I kept dialing, kept talking, kept pitching the dream of these glowing houses that captured Lviv’s spirit.

Slowly, we found our people. We tracked down a craftsman who’d worked with Ostap years ago and knew his quirks, and a couple of artists who were drawn to the studio’s mission of preserving Lviv’s architectural charm in light. Each new member brought their own skills, but more importantly, they bought into the vision. They weren’t just hired hands; they became part of a family, united by a love for Ostap’s art and a determination to keep the lamps glowing.

It wasn’t smooth sailing. Teaching new craftsmen Ostap’s technique was like trying to explain a dream—half the time, you’re not sure if you’re making sense. We had late nights in the workshop, poring over his blueprints, arguing over how to get the perpendicular glass just right for that signature glow. There were moments when I doubted myself, wondering if I’d overreached by pulling all these people together. But every time a new lamp was finished—whether it was a custom order for a client’s anniversary or a whimsical “fairy house” for our gallery—it felt like a small victory. We were keeping Ostap’s legacy alive, not just through the lamps but through the community we’d built.

That period of scrambling, calling, and convincing showed me what resilience really means. It’s not about having all the answers; it’s about refusing to let the fire go out, even when the odds are stacked against you. By the time we had five craftsmen working together, the studio wasn’t just surviving—it was thriving. New designs were coming to life, from intricate replicas to original pieces that carried Ostap’s spirit. Clients were delighted, and our little family of artists became a cornerstone of the studio’s identity, as you can see on budynochky.com, where we share our story and showcase our work.

I’m proudest of how we turned a crisis into a community. When Ostap passed away in 2023, that family of craftsmen ensured his technique and vision lived on. For anyone reading this, whether you’re a potential client or just curious, know that every Pavlovsky lamp is a testament to resilience—ours, Ostap’s, and now yours if you choose to bring one into your life. Visit budynochky.com or our Lviv gallery to see what we’ve built, and let’s keep the light shining together.

Contact Info:

- Website: https://bugynochky.com

- Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/budynochky?igsh=MXNwbGxtNzZhdHFuZw%3D%3D&utm_source=qr

- Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/share/12K3tTDFkhV/?mibextid=wwXIfr

Image Credits

Igor Tkalenko