We caught up with the brilliant and insightful Hannah V Warren a few weeks ago and have shared our conversation below.

Hannah V, thanks for joining us, excited to have you contributing your stories and insights. We’d love to hear the backstory behind a risk you’ve taken – whether big or small, walk us through what it was like and how it ultimately turned out.

With one large suitcase and one backpack, I said goodbye to my husband in Atlanta’s international terminal. At this point, the Fulbright wasn’t in danger of dissolution from the American government’s slashing of intellectual and creative support: I was leaving to spend a year in Germany’s Black Forest, working on aesthetics theory research and a poetry manuscript. The longest I’d spent out of country was a study abroad many years before in undergrad.

An academic and a poet from a working-class background, I live on the fringes of two cultural spaces. I’m from the rural Deep South, a small town in Mississippi known for little outside of its fraught history. When I left Mississippi after graduating college as a first-generation student, I left everything. The backroads and swamplands held family violence and belief systems that no longer defined me. I didn’t write about the uncomfortable parts of my identity—the trauma based in poverty, abuse, religion, and misogyny—but I held onto that invisible narrative. It wasn’t until I moved back South that I recognized how the cultural and natural landscapes I thought I’d left behind continue to inform my creative and academic work. I devoted a large portion of my doctoral studies to exploring Gothic aesthetics—aesthetics I grew up steeped in—with a focus on literary representations of women as monstrous and grotesque figures. My research led me to Germany.

During my Fulbright year, I took a transatlantic approach to aesthetics, seeking to understand how the German Gothic informs contemporary monster theory and how this inheritance has infected global literature over the centuries. With this knowledge, I created my own poetic lineage, tracing Kant’s theories on the sublime to modern and contemporary Southern Gothic poets like Ansel Elkins and Frank Stanford. My collaboration with German poets, such as Alexandra Bernhardt, during the Fulbright helped develop my knowledge in translation theory. I’ve received a Pen/HEIM Translation Fund Grant and a place at the Bread Loaf Translators’ Conference to continue this work. Translating contemporary German poetry now directly impacts the way I think about language and reader-response.

The last time I saw my husband at the Atlanta airport felt like a severance, but I was too distracted by the antics of survival to pause and reflect. Moving across an ocean, disrupting the standard expectations of an American marriage, didn’t pose a risk—but facing the bureaucratic nightmare of living abroad without the in-person support of a partner I’ve known most my life grew more daunting with every appointment, especially in a region where German is still very much the expected language in official interactions.

This risk-taking year made me braver: after graduating the PhD, I took a year to write and freelance edit, determining next steps inside the academic job market, my writing career, my personal life. My husband and I are buying a house in Birmingham, AL, even as I plan a career-advancing move to Ohio where I’ll write and teach at Kenyon College for two years. Risk, to me, doesn’t align with physical danger—rather, risk culminates in a blurry future, one that doesn’t hold promises of ease or gentleness. I’ve never regretted taking a chance.

Great, appreciate you sharing that with us. Before we ask you to share more of your insights, can you take a moment to introduce yourself and how you got to where you are today to our readers.

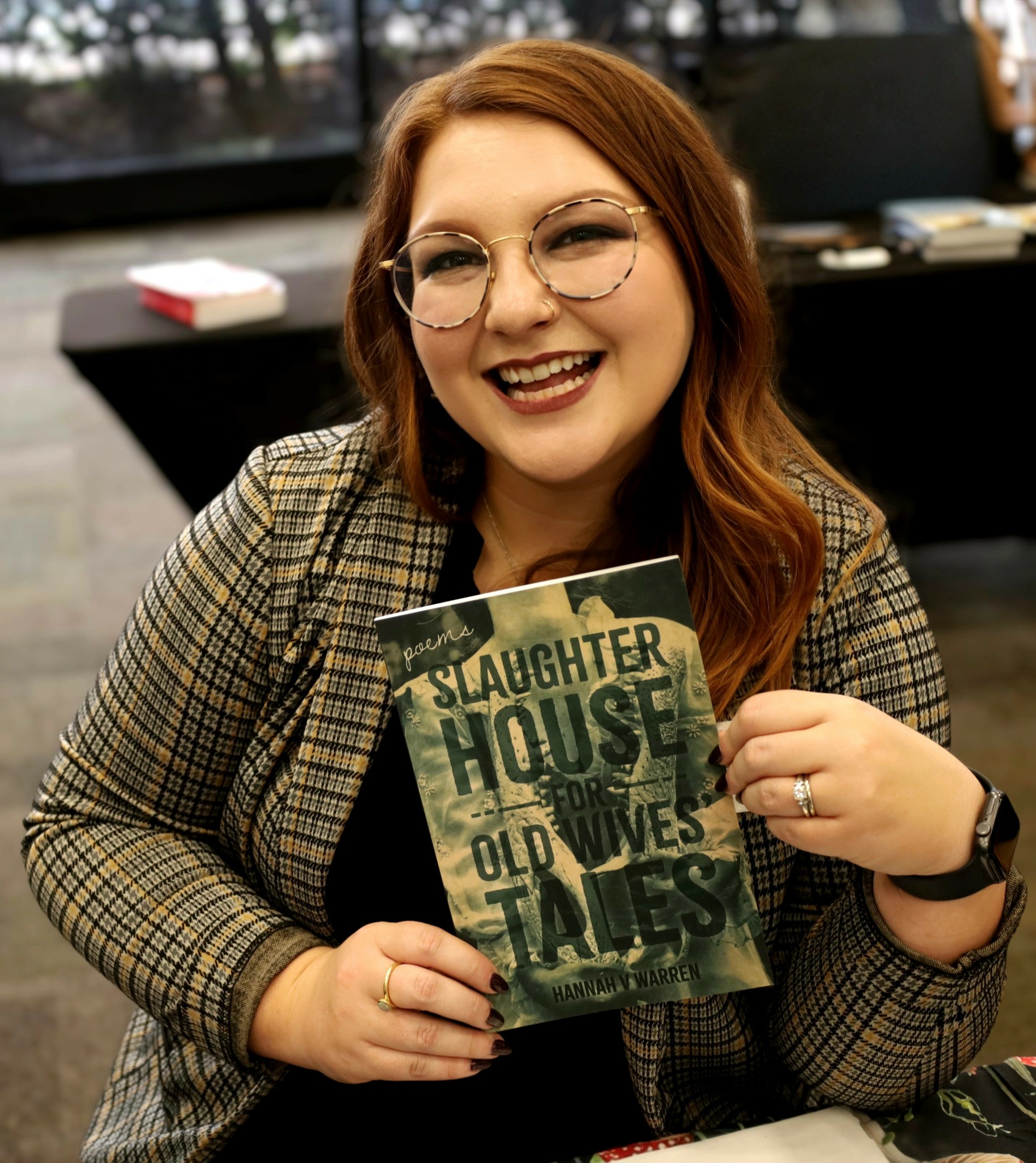

I’m a poet, translator, literary critic, and Fulbright Scholar—and one of my favorite ways to use this knowledge is working with novelists and poets to compose and revise writing projects. I have a PhD in Literature and Creative Writing from the University of Georgia and an MFA in Creative Writing from the University of Kansas. My full poetry collection, Slaughterhouse for Old Wives’ Tales, debuted with Sundress Publications in January 2024. Carrion Bloom Books published my chapbook Southern Gothic Corpse Machine (2022), and [re]construction of the necromancer (2020) received Sundress Publications’ annual chapbook award. Across my research and writing, I use aesthetics theory and my research in Gothic literatures as a lens through which I examine how grotesque and monstrous figures represent our cultural fears.

In her essay “Refraction as Rupture,” Jennifer S. Cheng claims that “we are always in the presence of ghosts, traces, shadows, echoes,” which is to say writing is always haunted by something that came before. As writers, creative and critical, we compose within a lineage singular to our experiences. In writing about monstrous women, I write about myself, grappling with my own subjective history. As writers, creative and critical, we compose within a lineage singular to our own identities, our devastations and joys, our unique combinations of lived experiences. Whereas I once tried to avoid this tug toward memory, whether abstract or direct, I now embrace it. No matter where they’re from, I encourage my creative writing students and freelance clients, as well, to pull from their own backgrounds and enrich their texts with lived experience.

What do you think is the goal or mission that drives your creative journey?

Alterity teaches us to believe in distance—an inherent divide existing between us and them. When we name someone monstrous, when we name someone other, we’re claiming that only we and those like us are allowed to identify with common human experiences. Only we and those like us have known the pain of losing a sibling to cancer or a car crash, the unfiltered joy of seeing the mountains take shape after miles of driving through the prairie, the consuming heartbreak of loving someone who doesn’t love us back, the anticipation of watching a horror film. All those human moments that make us feel alive and real. The beautiful. The sublime. When we label someone monstrous, we strip the human experiences that form our collective identity, casting them into the nonhuman—a distant category removed from human empathy.

I’m interested in how we determine what defines them—the monstrous other opposed to our definitions of selfhood. What makes a monster, and how do we go about solidifying that meaning? My poems wrestle with learned alterity. So often, women from the American South—and, historically, women everywhere—are labeled sinners, unclean, agents of the devil, dangerous. Monstrous. I lean into this unwanted moniker in my poetry as a method of critique. Even when I intend to write about something else, I circle back to the grotesque, the uncanny, the abject—all these aesthetic categories that solicit disgust.

Combining natural history and folktale, my poetry collection Slaughterhouse for Old Wives’ Tales (2024) explores the Southern Gothic geographic, political, and religious landscapes that formed my identity. Composed of interwoven poems that backtrack and often stutter over repeated ideas, this collection follows a second-person narrator from childhood to adulthood, exploring what it means to survive abusive relationships and cataclysmic events while becoming more monstrous, herself. My current project, Hurricane Pastoral, enfolds and stretches the aesthetic and discursive values of monstrosity. Extending and building on my previous work, women’s Southern Gothic experiences inform the root of this poetry collection, and I weave other monsters into my poems as speakers and fearmongers as I consider how media portrays women as monstrous figures across time and space—the same rhetoric that poisoned the well of my hometown. New faces, same story.

How can we best help foster a strong, supportive environment for artists and creatives?

It’s crucial to remember that nearly every form of entertainment we consume was once the scrap of an idea—an art project in the making. Your favorite movie, a local band’s concert, your grandmother’s blackberry cobbler, botanical gardens, the fruit bowl on your kitchen counter, a precisely placed feather on a shelf. Anything prepared with others in mind—or even the self in mind—relies on artistic and aesthetic skill. We live in a social landscape, and social landscapes create art. To best support artists, we must abort our comfort zones and embrace a willingness to learn something new. Our best resources are natural history museums, concert halls, movie theaters, coffee shops—gathering spaces for people to collectively enjoy art. Buy art. Get a library card. Go to the free museum lecture. Engagement is the best way to support a thriving creative ecosystem. Support can be monetary, social, and/or contemplative. In my field, people support creative writers by joining book clubs, forming writing groups, attending workshops, asking public and university libraries to purchase book copies, or writing reviews online. And, of course, buying and reading books.

Contact Info:

- Website: https://hannahvwarren.com/

- Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/hannahvwarren/

- Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/hannahvwarren

- Linkedin: https://www.linkedin.com/in/hannahvwarren/

- Other: Bluesk : https://bsky.app/profile/hannahvwarren.bsky.social