We were lucky to catch up with Guen Montgomery recently and have shared our conversation below.

Hi Guen , thanks for joining us today. Can you talk to us about a project that’s meant a lot to you?

There are a lot of ways to make meaningful work. Sometimes a thing is meaningful through direct, impactful actions, sometimes a work’s meaning is in its ability to change the internal landscape of the viewer, or affect them emotionally. I think my recent work from the animal-creature series “Crawl Space” is psychologically impactful and resonates with people. However, the most meaningful work I’ve made in terms of direct action is probably my “No Dumping” project. In “No Dumping,” I installed a color-core polymer sign (the kind you see in National Parks) alongside the gravel ridge road my mom drives to get to town every day in rural Scott County, Tennessee. The simple cnc-routed No Dumping sign asks viewers to “Keep Scott County Beautiful,” directing them to the nearest free dump. It borrows from the implicit authority and conservationism of visually similar signs installed by city governments and parks. I created and installed this work in response to my ongoing mother’s frustration that folks would drive their trash out to the road near her house and dump garbage over the ridge. Folks would dump all kinds of things they didn’t know how to get rid of into the ravine: pig carcasses, bathtubs, mattresses, old tires, plastic jugs, glass bottles and bags of trash. This part of east Tennessee, the Cumberland Plateau, is particularly beautiful with lush rolling hills little mountain ridges. During the summer, bright red salmon berries, known colloquially as “tayberries,” grow along the ridge and folks pick them by the bucket. The berries grow right up around the trash and kids were getting tangled in the mess when they tried to pick the berries. It’s never been clear who actually owns this property. It might belong to the city, or one of neighbors who have big swaths of land nearby. So, I made a sign, and with my mom driving the get-away-car, we covertly installed it one Christmas morning when no one was around. We figured it would quickly get taken down or used as target practice. Instead, almost 8 years later, the sign still stands, and someone lovingly mows around it every couple of weeks. I wasn’t convinced that a sign, even a beautiful, convincing sign, has the authority to change human behaviors, but it did: people now dump their crap a few yards down on the other side of the ridge.

Great, appreciate you sharing that with us. Before we ask you to share more of your insights, can you take a moment to introduce yourself and how you got to where you are today to our readers.

I am a professor and studio artist living in Urbana, Illinois. I teach at the University of Illinois, Urbana Champaign. I live with my wife, my 2-year old daughter, two cats and a very patient dog.

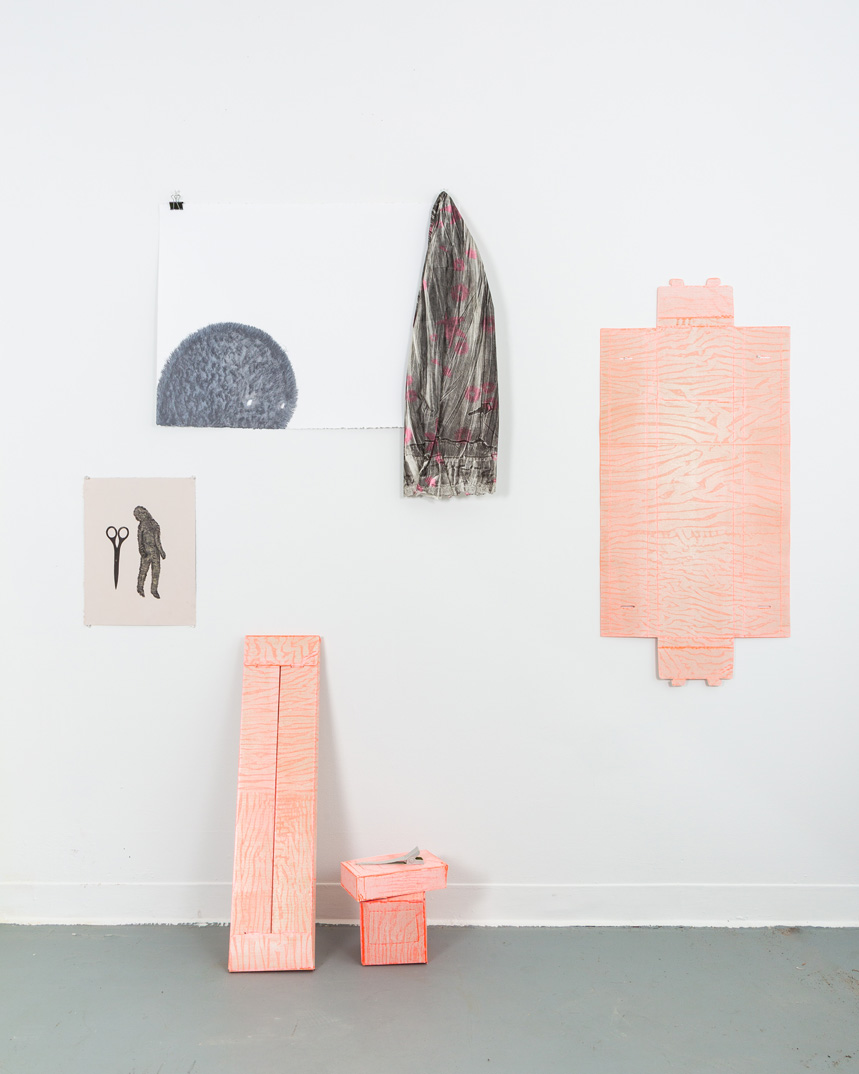

My artwork tells stories about the absurdity of gendered personhood in the material world. I combine collagraphic prints with sculptures and performances in installations. I have a printmaking background and often make prints from objects and textiles through the collagraph-adjacent process of applying ink directly to the object and running it through a big etching press. I’ve printed many family heirlooms like house dresses and slips. I love making work this way because the image is all about layers of texture and the objects appear more real when printed than they do in life. I also like the idea of the actual object being the source of the print instead of a rendered matrix (the block or screen a print is usually made from,) making the print more like forensic evidence than representation. The garments I’ve printed, and resulting installations, suggest hyper-femme archetypical characters influenced by Betty and Veronica comics, my Appalachian granny, and my power-suit clad 80’s super-mom.

In the recent series Crawl Space, I tell new stories through sewn & printed furry pelts. These prints and pelt-forms are animal-creatures who are trying to navigate what it means to be an organic mammal-person afloat in oceans of possessions and constructed environments. My connection to the narratives around material culture (the stories about human stuff) stems from my family’s fraught relationship to things. They covet, collect, curate, hoard, and hide objects away. Rooted in rural Tennessee’s Cumberland Plateau, I see my family’s relationship to the material world as something culturally deeper than generational poverty, or “having not.” My family, in their rock collecting and junk hunting has a different understanding of value and an aesthetic that’s informed by Appalachia. I understand my mother, aunts and uncles through their relationship to their things and understand my things through my family’s culture.

I wonder what our stuff does to us psychologically. I also wonder if our stuff, in its permanence, ubiquity, and mass, is becoming more real than we are. As we outsource our brains and neglect our humanity, are we moving closer to becoming objects ourselves? I make art to tell stories and think through these ideas.

Is there something you think non-creatives will struggle to understand about your journey as a creative?

I think it’s hard to understand why, in a time of political, economic, and environmental crisis, one would pursue anything that isn’t a straight-forward path to financial security. For those questioning the wisdom of pursuing art, I would first admit that being an artist is certainly not a straight path to a career. It requires a willingness to patch-together positions, invent your own opportunities, and will probably not make you rich. I am lucky that I can rely on teaching the skills I use to make my art through my position at a university to sustain my life. When I was a nanny with no impressive job prospects, I still made art because I had to, it’s part of being who I am. Ultimately, choosing to be an artist is driven by necessity; it’s choosing to be who you are in your fullness, despite capitalism and its demands. You have to have some money. But there are many things more important than having more money. Even in times of scarcity, I believe we do better and are better when we seek fulfillment through curiosity, creative acts, care for others, and psychophysiological ‘wholeness’ beyond that promised by paths driven by accumulating economic capital or status.

In your view, what can society to do to best support artists, creatives and a thriving creative ecosystem?

Believe in and promote a culture that values art beyond its service to the economy or promised technotopias. Art matters because it changes us. We need it to make meaning, tell stories, remember, empathize, interrogate, and help us to imagine different futures. Change your own mind about the function of art in society and then tell other people about it.

Contact Info:

- Website: https://guenmontgomerystudio.com

- Instagram: @guenstagram

Image Credits

Will Arnold