We recently connected with Greg Fields and have shared our conversation below.

Greg, thanks for joining us, excited to have you contributing your stories and insights. When did you first know you wanted to pursue a creative/artistic path professionally?

I had worked in the non-profit sector all my professional life – public relations and fundraising for universities, and then for a magnificent international development organization. But all along I had played with my writing, penning short pieces that I never shared, extremely bad poetry and the occasional opinion piece. I always felt comfortable putting my thoughts down in some way, but I really had little expectation that it would ever come to anything.

Several years ago I was finishing what turned out to be my first novel. I had begun it in part as a reflection, in part as a catharsis. in part just to see if I could do it. As it was nearing completion, my wife bought me a ticket to a VIP reception after a lecture by my literary hero, Pat Conroy. Not knowing anyone in a crowd of 50 or so, I made my way to the hors d’oeuvres table so that the event wouldn’t be a total loss. As I loaded my plate with cocktail shrimp, I felt a hand on my shoulder.

“We’ve not met. I’m Pat Conroy.”

We ended up talking one-to-one in a corner of the room for about 25 minutes while everyone else circled about. We learned we shared the same birthday, the same literary influences and many of the same experiences. When I told him I was in the midst of writing my first novel, he asked if I could recite any of it. I was able to cite some of the Prologue, after which Pat became quite serious and told me that he would like to read it and, if it were all that good, he would be pleased to offer a jacket quote. We corresponded after that, he offered advice and insights, and helped polish what I had. Pat passed in early 2017, shortly before the novel was finalized. We’re all the poorer for it.

But through the thoughts we shared, Pat showed me something in my writing that I did not have the courage to see for myself. His encouragement validated me, humbled me, challenged me, and, in the end, convinced me that I might be good at this, a conclusion that I had dared not reach.

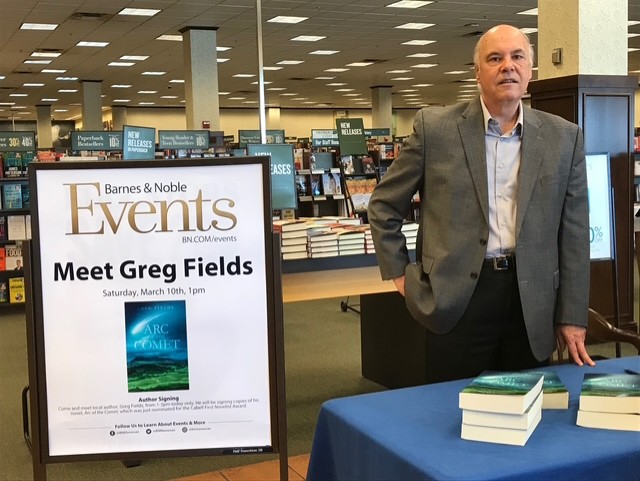

I published my first novel, Arc of the Comet, with Koehler Books in 2017. Despite Pat Conroy’s influence, I loo at it as something of an embarrassment. It’s long, it’s rambling and it takes forever to find its focus. Under Koehler’s guidance, I learned a bit about how to write the next, which they published in 2021. Through the Waters and the Wild won a host of national awards, and my confidence grew.

In the meantime, John Koehler asked if I could come on board as an editor. I’ve been part of Koehler’s team since 2019.

My third novel, The Bright Freight of Memory, was a risk for me, written in a new format with characters and circumstances outside my comfort zone. It was released in November 2024, and it’s exceeded all my expectations. It’s won a number of national and international awards, including the American Writing Award for Literary Fiction, The Southern California Book Festival Book of the Year across all genres, and the Chrysalis/BREW Project Book of the Year. It’s been nominated for a PEN/Faulkner Award (which it has no chance of winning, but still…..).

Now, after all this, I’ve arrived at a place beyond any fantasy I ever had. I make my living now through literature, either my own or the incredible works of new writers who come to me through Koehler. The editing is gratifying to the extreme, helping the journey of those with similar aspirations. I learn from every writer with whom I work. I’m a better writer because I edit, and a better editor because I write.

Most of the writers are publishing for the first time. They have questions about the processes, the deadlines, the deliverables. They’re excited and just a little bit afraid. They’re in a place that almost all writers pass through on their way to other things, so I try to offer them more than just editorial help. It can be an unsteady journey, and I try to help them through it.

But I also know none of this would have been possible without an immense dose of good fortune. The night I first met Pat Conroy I sat up until the wee hours, reflecting on the incredible chance that had come my way. When I found a publisher who genuinely cares for his writers and their art, I sought his advice and counsel at every turn.

Each day I’m thankful that it all came together the way it did.

Greg, before we move on to more of these sorts of questions, can you take some time to bring our readers up to speed on you and what you do?

I think we live our best lives when we’re sensitive to what’s around us, when we seek a harmony with those with whom we live, the strangers we pass on the street, and, most importantly, with ourselves. That harmony – that sense of being who and what we are best meant to be – is precious, and it is exceedingly rare. My mentor, Pat Conroy, wrote “From the beginning, I wrote to explain my own life to myself, and I invited readers who chose to make the journey with me to join me on the high wire. I would work without a net and without the noise of the crowd to disturb me. The view from on high is dizzying, and instructive.”

When I write, I try very hard to be in tune with the circumstances that fascinate me enough to try to put them into words. All of us are individuals seeking the right place in a pluralistic, complex society, and all of us have the quirks, neuroses, joys, and traumas that make us unique. There’s such richness in the human spirit, and how that spirit strives, achieves, fails, mourns, and ultimately perseveres against the obstacles it inevitably encounters. And in the process of regarding this incredibly bright and rich fabric, I learn a bit more about myself, my own mistakes, and how the random, almost accidental events of our lives shape who we are.

I love the music of the language, the way it can soar and sing in amazing ways that can transport thoughts and ideas to new heights, and, in the music of it, make the indelible. Pat Conroy massaged the language better than any writer I’ve ever read. I told him once that on my best day I couldn’t come close to what he could do on his worst. (He smiled, but he did not disagree).

There’s a danger in all this, of course. In college I had an English professor who once told me, “Mr. Fields, you write as if you had just swallowed a dictionary and are now burping up words.” He was right. I have a tendency to fall in love with the cadence of what I’m writing at the expense of clarity, focus and purpose.

The world is in a very precarious place these days. I think at every turn we need to affirm the collective values that build community – inclusion, respect, kindness, and the commitment that each individual carries a dignity that should never be compromised. So writers, I think, have a responsibility to represent our commonality, the things that bind us as human beings and transcend any label. That’s been the point of my own writing, and something I think I share with the great writers who even more forcefully throw themselves against the madness. I think of James Baldwin, Toni Morrison, Upton Sinclair, and the countless others who used their narratives to reflect the best of what we might and should become.

My themes are less political and more personal. Still, I think the coming together of community begins with the realization of self. Once we feel comfortable with who we are as individuals, we can much more easily become part of something larger, something nourishing and real.

In your view, what can society to do to best support artists, creatives and a thriving creative ecosystem?

The arts have always been marginalized, I think. We’ve regarded the arts as decorations or pastimes, things that amuse and distract rather than enlighten. We’ve seen it in schools that cut their arts programs at the first sniff of budget problems, at the state level where arts programs have to wrestle for their funding, and, maybe most obviously, at the national level when each year institutions like the National Endowment for the Arts have to argue for their relevance. And I think it’s all about to get worse.

In Dead Poets Society, Robin Williams’ character very passionately tells his students: “We don’t read and write poetry because it’s cute. We read and write poetry because we are members of the human race. And the human race is filled with passion. And medicine, law, business, engineering, these are noble pursuits and necessary to sustain life. But poetry, beauty, romance, love, these are what we stay alive for.”

We run the risk of losing that vision, of discarding the things that keep us uniquely human for the sake of one more account, or one more client, or one more dollar.

I have no solution to this other than a collective redirection of our priorities. We need to recognize the role of artists who challenge us to stay true to our shared humanity and to chase our better angels. And we need to recognize that the contributions of a painter or a sculptor or a playwright are as valuable to our well being as that of any corporate executive, and reward them accordingly.

For you, what’s the most rewarding aspect of being a creative?

I’m always gratified, and maybe a little surprised, when a reader tells me that something I’ve written stirred them in some way. Every writer seeks connection. We all want to know that the work we’ve done, and in which we’ve invested a sliver of ourselves, has reached another soul and provoked a response. I’ve had readers tell me that my writing is ‘beautiful.’ But I know that beauty is subjective. What’s not subjective is honesty, and I try very hard to write openly and without pretense or manipulation.

In the end, I feel as if I have a voice. It may be small and very quiet, and only a few people may hear it, but it exists. And with that voice is a platform to explore our shared aspirations, anguish, traumas and joys. To be connected and to be part of one another’s journey – that lies at the heart of what I do.

Contact Info:

- Website: www,gregfields.net

- Facebook: GregFieldsAuthor

Image Credits

Headshot – Steve Johnson Photography