We recently connected with Greg Edmondson and have shared our conversation below.

Greg, thanks for joining us, excited to have you contributing your stories and insights. How did you learn to do what you do? Knowing what you know now, what could you have done to speed up your learning process? What skills do you think were most essential? What obstacles stood in the way of learning more?

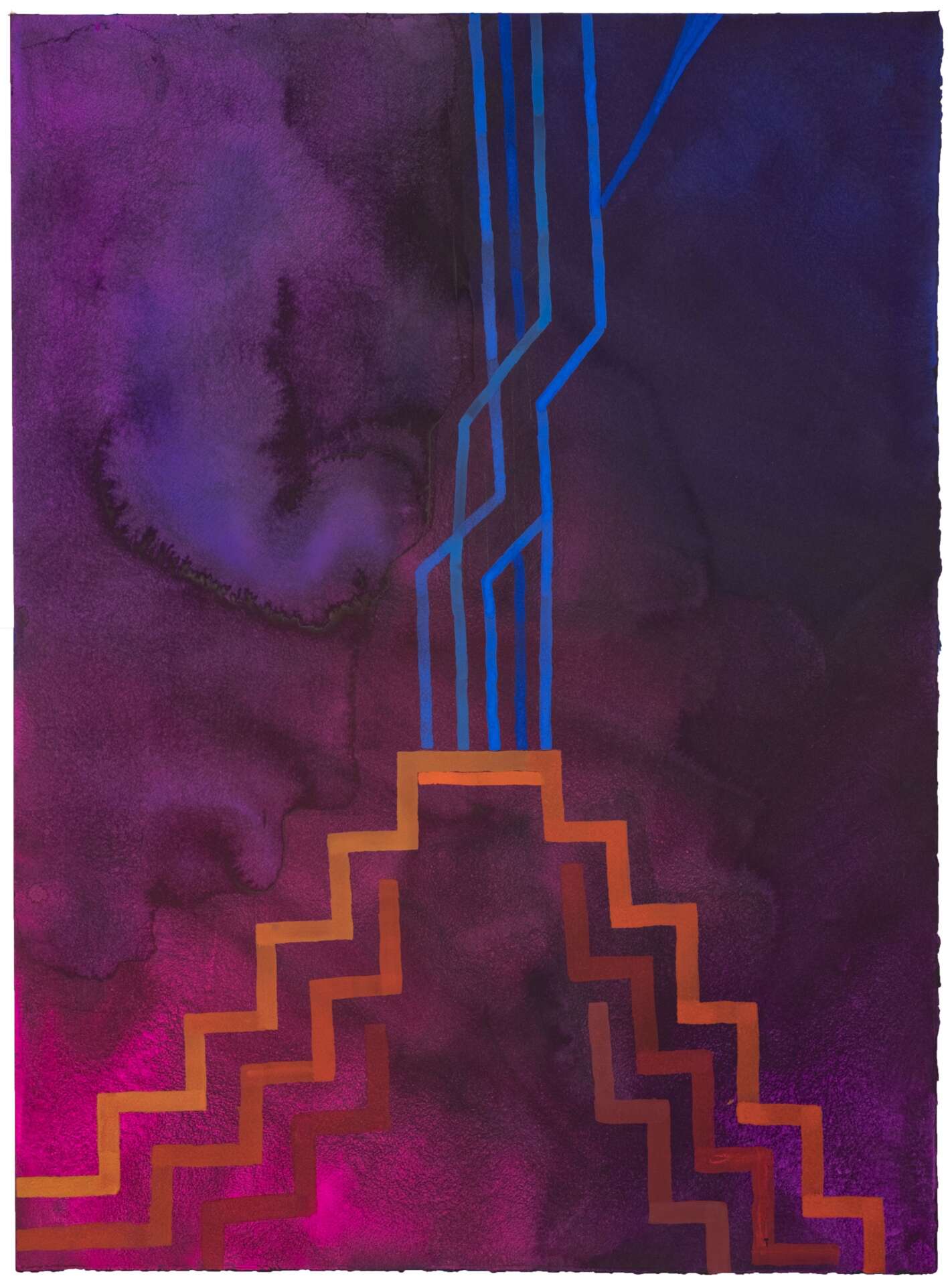

I started college as a biology student, and was raised by a pair of musicians. It might at first sound strange to say that an interest in the natural world and its patterns of organic growth and decay – or melody, harmony, tonal structure and discord could form a basis for what I do as a visual artist, but it’s true. I’d been drawing pictures since before I could remember, but knew almost nothing about Art with a capital “A”. I’m from a small town, my parents were from smaller towns, and art just wasn’t a part of our household. When I was pretty sure I wanted to change my college major, but hadn’t yet been brave enough to do it, I took a couple of painting classes as electives. But it was an art history course that made the decision for me. For the first time I saw artists from 50 years ago, 100 years ago, 500 years ago, who were grappling with the same ideas, fears and desires that I was experiencing. It made me feel like I could become part of a long tradition instead of just being that lone weirdo who liked to draw..This was the 1970s, and many of my faculty had ,cut their teeth on the big abstraction of the 50s and 60s. I was excited by what I saw, but I didn’t understand it at all… How could just color be the whole subject of a painting, how could forms that don’t depict anything specific interact with each other in such powerful, evocative ways?…

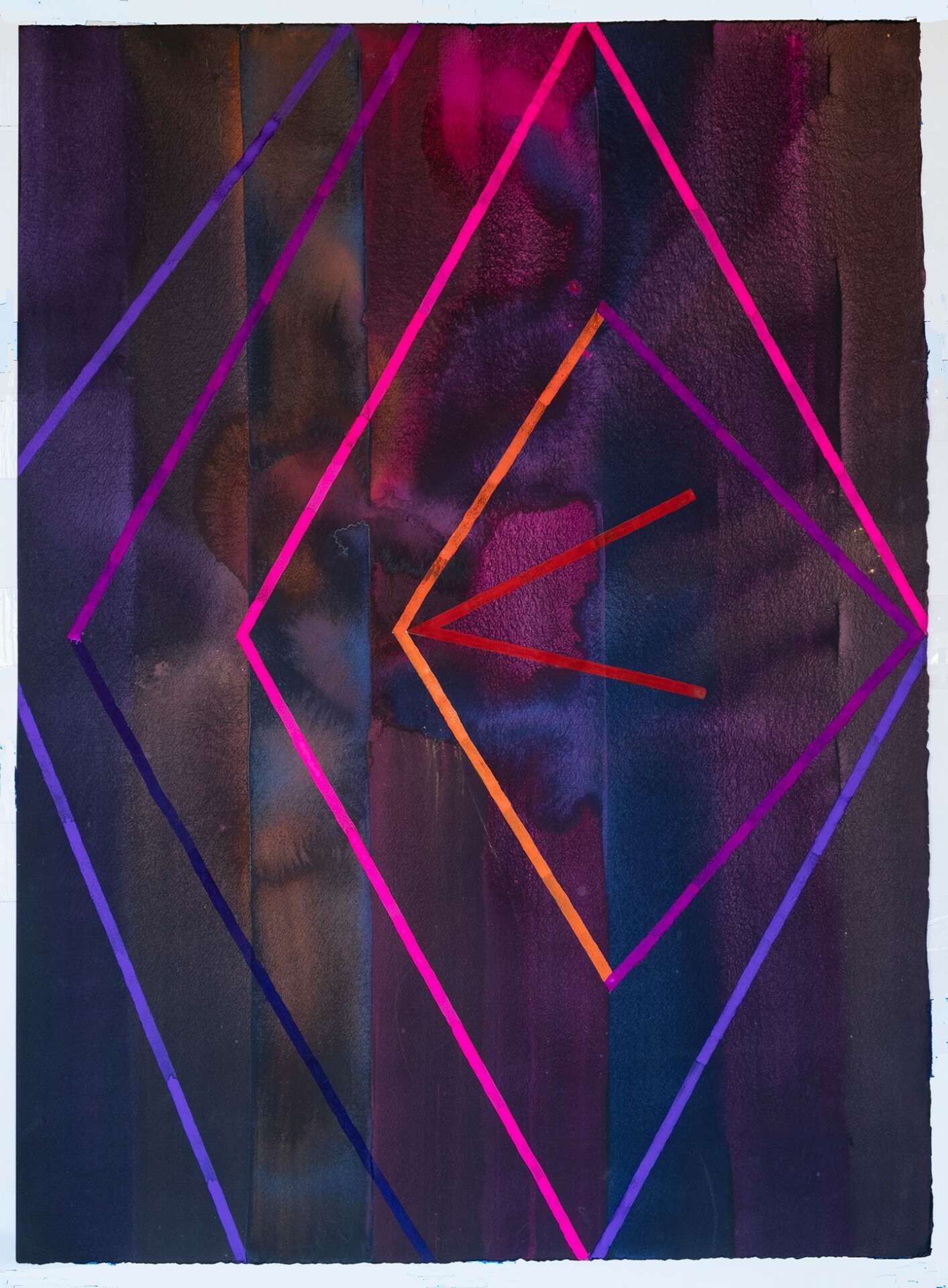

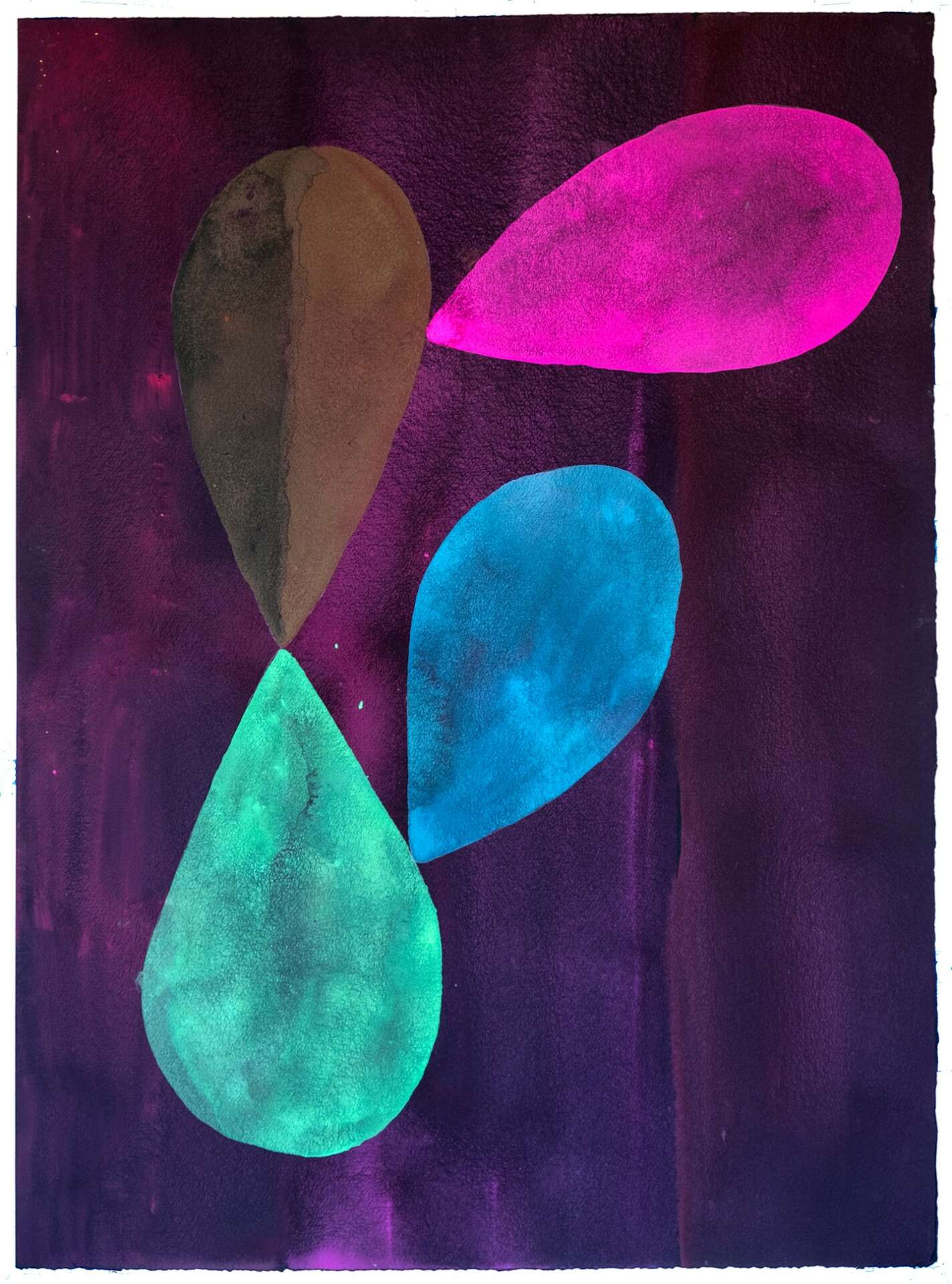

It took a long time to realize that color and form could be used in the same abstract ways that musicians use chord progression, melody, harmony or refrain. That repetition and discord, melody and harmony could be seen as easily as they could be heard and that a painting could be built the way music was composed. This was really a watershed moment, and one that still drives much of the work I make today. Another critical step was learning to view my studio as a “laboratory”. Treating the studio as a place to conduct experiments, and to dispassionately observe the results of those experiments showed me new pathways forward. This practice still helps me navigate my way from painting to painting, and especially from series to series.

Over the years my work has ranged widely, at times far away from my initial interest in abstraction. I’ve learned printmaking, mold making, wood and stone carving, welding and fabrication… (you never know what you might need to know or where that new knowledge might take you) . But I always find myself circling back to formal abstraction. When you’re dealing with the purely abstract, you’re never dealing with a “what”, but always with a “what if”. You can turn it upside down, you can cut it in half, anything is possible. And that’s both exhilarating and terrifying. I’ve been a working artist for four decades now, and I feel like I’m finally starting to get the hang of it. I guess I mean that learning the craft is a moving target, and that learning really is the point. You’ll never make the “perfect painting”, thankfully there’s no such thing, If there was we would all be moving in the same direction rather than in the multitude of directions our thoughts and actions can take us The more I learn, the more I realize there is to learn. So instead of answers, I just hope I can keep finding better questions… and making better paintings.

As always, we appreciate you sharing your insights and we’ve got a few more questions for you, but before we get to all of that can you take a minute to introduce yourself and give our readers some of your back background and context?

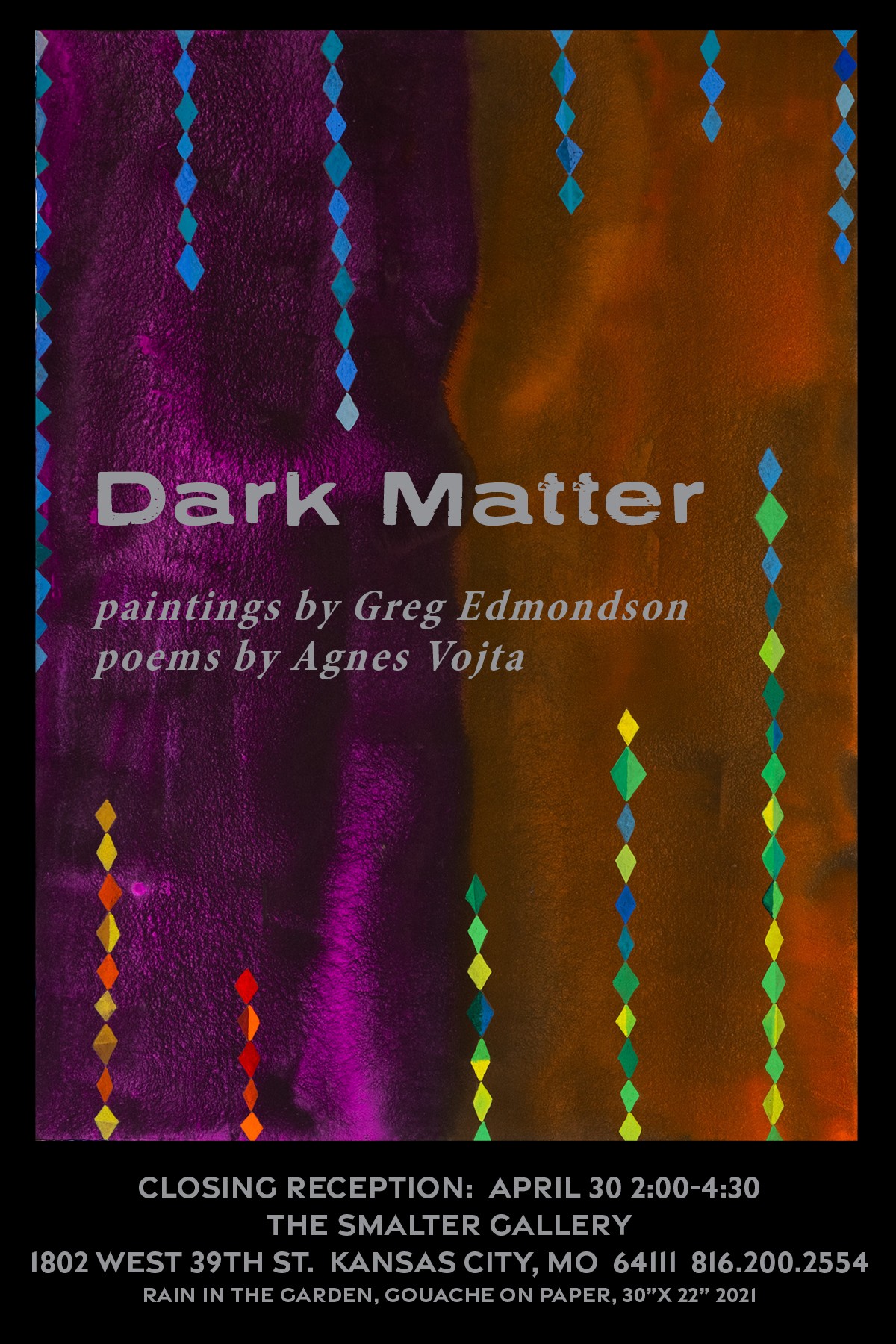

I’ve been a working artist for four decades, which means I’ve also been a college professor, a candle maker, a carpenter, a curator, a set designer, an artist-in-residence… all while maintaining an active studio practice and exhibiting work both at home and abroad. (I was even a truck driver for two years hauling art all over the country) Being an artist for a long time can lead you to wear a lot of different hats, but you usually gain something of value from each experience. I have particularly enjoyed being involved with Artist Residency Programs and the opportunities they offer to interact with other creative people from a variety of disciplines and cultural backgrounds. I really love collaboration with artists whose work takes other forms than my own. Most recently, I collaborated with writer jonathan kline on the cover for his latest book from Lavender Ink Press in New Orleans, and with physicist and poet Agnes Vojta for an exhibition of paintings and poems titled “DARK MATTER” at The Smalter Gallery in Kansas City. I have two shows coming up. A two-person exhibition with painter Lisa Bergant-Koi at Studio Break Gallery in Chicago this April, and a five person show with Habitat Contemporary in Kansas City this July. I’m always looking for new opportunities to exhibit the work I’m making, to interact with students and young artists, and talk with interested people about the work I do, and the experiences that have taken me here.

Have you ever had to pivot?

I think most of us who have spent a life in any type of creative pursuit have had to pivot more than once. It’s not a path that’s particularly predictable and learning to roll with the circumstances is often a requirement. In 2014, after running an art program and a gallery for 15 years, the institution I worked for got a new president. She dissolved the entire art program, and thanked all of us for our years of service. It was so abrupt, I really was at a loss as to what I should do next. Out of the blue, I was offered a position as an Artist-in-Residence in rural Missouri on the banks of the Gasconade River. So on April Fools Day of 2015 I put most of my belongings in storage and left my live/work space in downtown St. Louis for a ramshackle cabin on a river, eight miles from the nearest gas station. I can’t say that the entire experience was positive, but it did force a significant and ongoing shift in my practice. I’d grown somewhat comfortable in my downtown studio and I wouldn’t be making the work I am now without this forced interruption and reset in a radically different environment.

We often hear about learning lessons – but just as important is unlearning lessons. Have you ever had to unlearn a lesson?

I think learning is a constant in the life of an artist. Which forces unlearning to be a constant as well. More isn’t always better, new isn’t always improved.. mastery isn’t the ultimate goal, (in fact it can get in your way). Staying hungry is as valuable as feeling sated… When you’re young and starting to do something like this, it’s easy to get hung up on the importance of “skill”. I mean, you’re doing something that most people think of as a hobby at best, so it’s understandably important to prove you’re really good at it. I’d always been that kid who could draw, and I thought that gave me some kind of advantage. But showcasing what I thought I was good at limited me. It limited the way I thought, and it limited the the things I let myself try. I slowly learned that a skill set was just a tool, and it was way more important to have a lot of tools than just one big, shiny, pretentious one.

Contact Info:

- Website: https://gregedmondson.net/home.html

- Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/greg.edmondson.315 https://www.facebook.com/voegel60/

- Other: https://www.saatchiart.com/GregEdmondson http://www.philipsleingallery.com/greg-edmondson https://www.davidlinneweh.com/studio-break/greg-edmondson?rq=greg%20edmondson https://www.stlmag.com/culture/visual-arts/tracking-an-artist-s-process-with-rivers-and-beasts/

Image Credits

Lisa Halley Melching