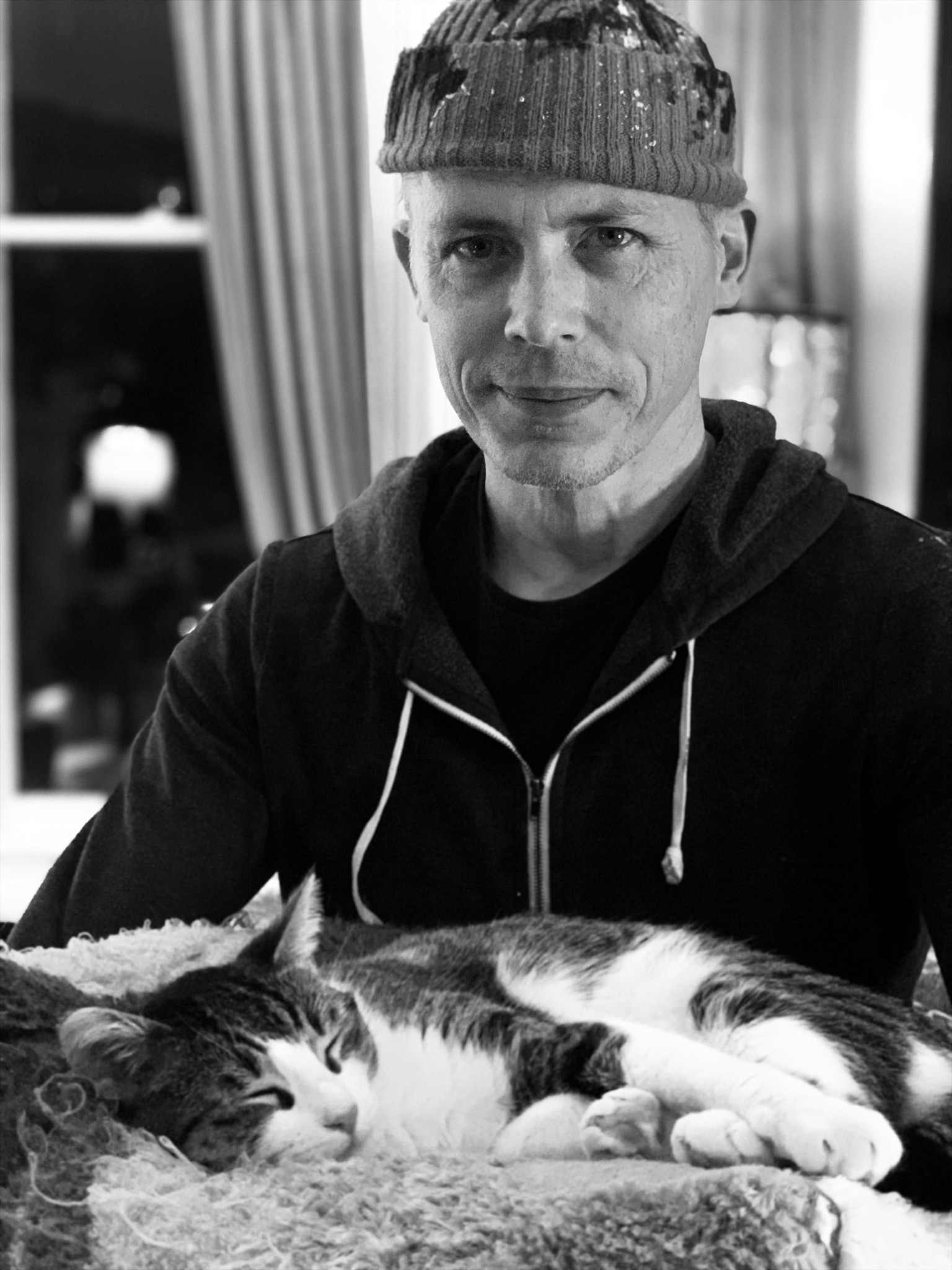

Alright – so today we’ve got the honor of introducing you to Felix Macnee. We think you’ll enjoy our conversation, we’ve shared it below.

Hi Felix, thanks for joining us today. Learning the craft is often a unique journey from every creative – we’d love to hear about your journey and if knowing what you know now, you would have done anything differently to speed up the learning process.

Learning to paint really started with learning to draw, and learning to draw began by sitting with my grandfather and watching him draw. Oddly enough, what I remember most when thinking back is the sound of his pen scratching the paper. It was hypnotic and intimate, seeing his thoughts become visible on the page. We’d sometimes look at cartoons in the New Yorker together, and though I didn’t always get the joke, I could see the life in the drawings. It was a language much more direct than words.

Later drawing became an escape. At nine years old, I moved with my mother from San Francisco to Wyoming, and went from real happiness in San Francisco to a pretty fearful place of isolation and domestic violence. We were poor, living in a trailer across the highway from a cement factory, and my mother had rushed into an abusive relationship. Looking back now, I have a lot more sympathy for her, and even for the man she ruined herself with. They were like two drowning swimmers, ripping each other down.

I escaped when I could into reading and drawing.

It’s a truism that drawing is the foundation of painting, but I think my painting has more in common with sculpture than drawing. What I saw in some of the greatest paintings was that they WERE something, rather than being ABOUT something. Standing in front of a painting, you could almost feel a body. Whereas in front of the greatest drawings, you felt a lyricism, or a brilliance, or an overwhelming skill. But paintings have a body.

I moved back to San Francisco when I was a teenager. I thought I wanted to be a writer. Or maybe play the drums. I had moved in with my father and stepmother and sister, and it was the first time I had felt happy in a long time.

When I realized I wanted to paint, I became obsessed. I remember in the early days, painting late into the night in a garage, not realizing how cold I was until I had to pry my fingers off the brush. Still, nothing was very good. I got angry with myself but kept going. I ruined many paintings.

There’s no substitute for hours of failure. You have to be okay with failing, and getting something good only once in a while. The ratio of failure to success can feel absurd, so the key is obsession. In order to keep going, each small success has to be really felt.

Felix, before we move on to more of these sorts of questions, can you take some time to bring our readers up to speed on you and what you do?

I’m a painter, and I’ve been working as a painter for 30 years. My grandfather was a painter and an art history professor in Chicago, and my mother and father were a poet and a musician, respectively.

It’s a running joke in my family that we all wish somebody would rebel and become a banker.

It really did feel inevitable that I would be an artist. For as long as I remember, it wasn’t even a question. I was always fascinated with science, logic, puzzles, and philosophy … but it felt like learning about such things was essential in order to be a better artist. I sometimes wonder how much simpler, and maybe happier, life could have been had I been a mechanic or carpenter. Something where I solve problems or build something. Because paintings are problems to solve, but nobody sees the problem — they only see the solution. Nobody’s car stops working if you make a bad painting, so it can be hard to tell if you’ve succeeded or failed in art.

I think what I’m happiest about is that I’m still painting after all these years. Everything is stacked against it, everything pushes you to do something more “normal.” I remember talking with my father when he was dying, and us both realizing that, even though he wasn’t famous, or rich, he had actually succeeded in doing what he loved for his whole life. The one thing you can’t get back is time. You can’t wait until the time is “right” to go for what you love. You really have to neglect other responsible things. At some point in your life, you have to know that the playing field disappears behind you, moment by moment.

Is there a particular goal or mission driving your creative journey?

My goals in making art have changed over the years.

In the beginning, my aim was the cleanest and most direct: to play. This is when making art is almost a closed loop. You play and you are rewarded with that play, you delight in the making and the result is almost secondary. The relation to an audience comes after that. You are your own audience. In that sense, there is no art. If you think of art as a kind of communication, then this is missing a separate, reflecting mind.

Even though this is kind of a shallow trajectory, it can be really productive. Some artists tap into this mindset to get a lot done. At its best, it is a kind of non-judgmental, meditative engine.

However, as soon as you think of an audience, the audience is there. Alone, you become your own audience. Maybe your first audience was a praising parent. Soon you start to have questions about quality, cleverness, relevance, talent, skill, value, etc. You compare yourself to other artists, you look at what you’ve done and ask yourself if it’s any good.

And this is where making art generally stops.

But if you really love painting, say, or maybe if you just have a big ego, you think that, despite being not very good, you might SOMEDAY be good, and so you keep working. This is where things can get going.

My mission when I reached this point was to make a really good painting, not for me but for the painting. I began to see each painting as being owed what it needed. And taking my desire to be seen as talented, taking that out of the picture, made painting easier. I could be more honest with myself about what was really good, versus what looked impressive. What the painting needed, versus what I needed. This attitude led to more bravery, and more willingness to make mistakes. Rather than clinging on to something that happened to be rendered well, I would ask, “does the painting need this?” And often the answer was no. Not only no, but actually, the painting is being made sick by this. The very thing that I thought was good was warping it like a misaligned bone.

Making mistakes is hard, and something we avoid, of course. But that can cripple you, avoiding mistakes. If you were told you needed to make a thousand mistakes before you understood painting, wouldn’t you start making mistakes as fast as you could? I don’t think I’ve made enough mistakes yet, and yet still it’s hard for me to feel free to do so.

I guess what this boils down to is feeling like a beginner. A real beginner isn’t afraid of failing, because small failures are expected and normal. So holding the feeling of being a beginner is my goal. Then, when I inevitably fail, I don’t have to be so hard on myself.

Recently my goals have evolved. Just because I have lived a while, many of my favorite people have died. Maybe I’ve become sentimental, but I think of the work as dedicated to the people who taught me how to make art, and why to make art. Unfortunately, this can make working feel heavy, and I think I need to remember my earlier ways. But it also feels good to want to be generous, to let the painting be for someone besides myself.

For you, what’s the most rewarding aspect of being a creative?

The best thing about being an artist is how terrifying it is. It’s terrifying, knowing you’re the first thing to go when things get tough, and yet what you do defines us as human. What you make is considered a luxury, but at the same time it is so essential that no human society is without it. It is the first thing that people do to mark their place in the world.

Contact Info:

- Website: https://www.felixmacnee.com/

- Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/felixmacnee/