We recently connected with Ekaterina Khromin and have shared our conversation below.

Ekaterina, appreciate you joining us today. Can you recount a story of an unexpected problem you’ve faced along the way?

((this is discussed in the following interview))

Awesome – so before we get into the rest of our questions, can you briefly introduce yourself to our readers.

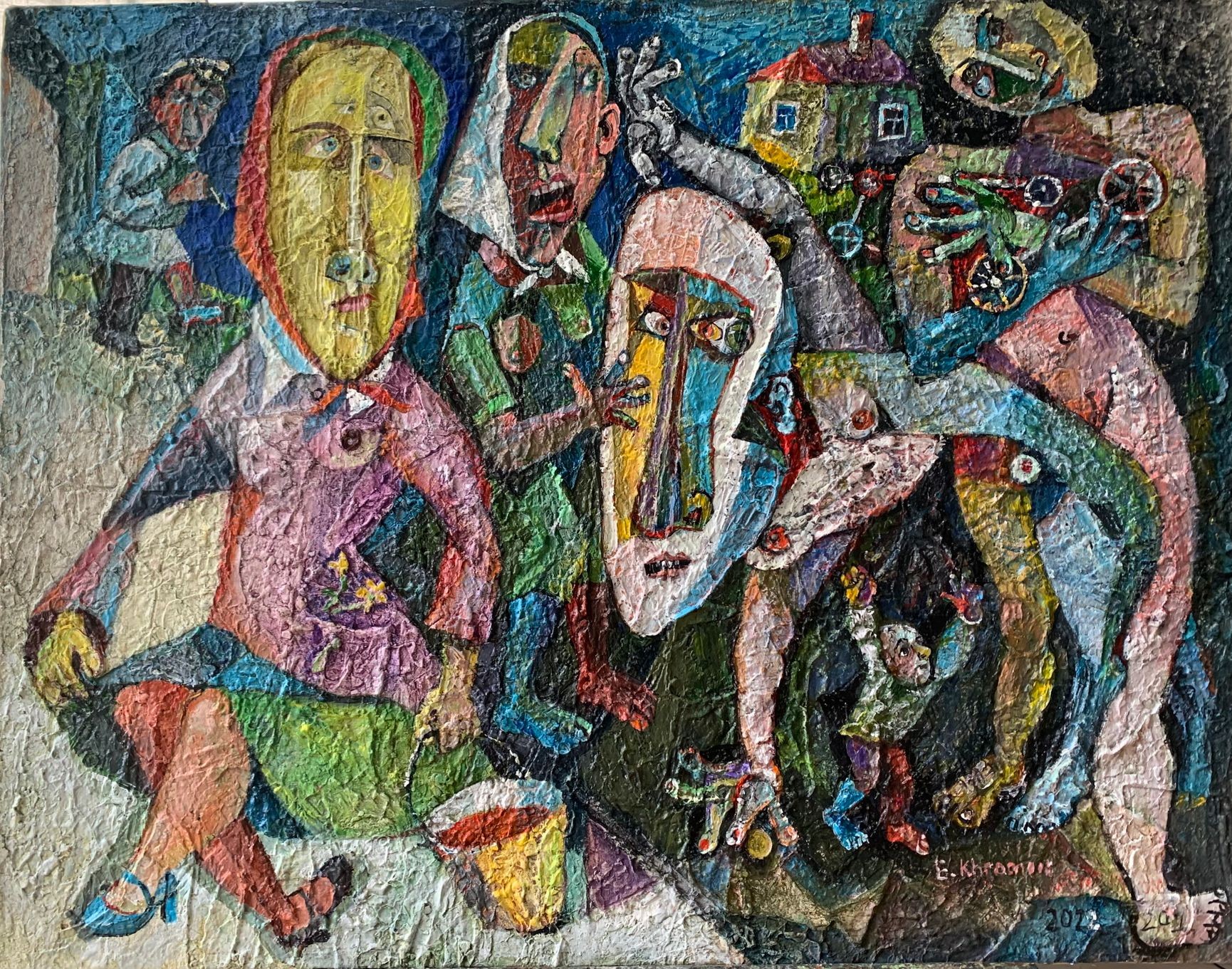

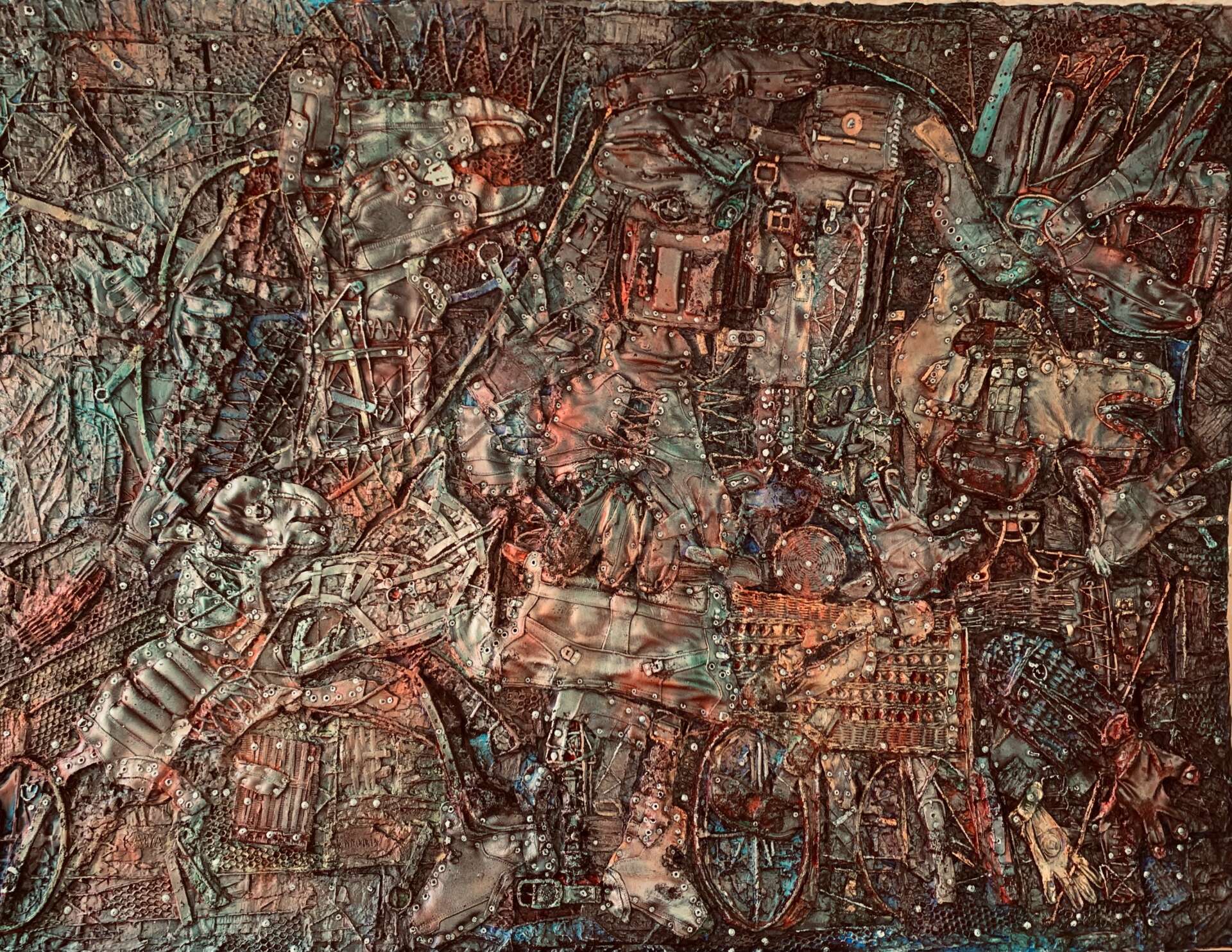

Ekaterina Khromin was born in Leningrad, now Saint Petersburg, Russia where she attended the Imperial Academy of Art. Her art career in the USSR involved the illustration of numerous books and art conservation. In 1990 she first came to the United States with her late husband for their art exhibition at the Nachamkin Gallery in New York City. Ekaterina and her husband were pioneering a new technique in nonconformist art. The artists immigrated because of the pressure of Soviet censorship restrictions on art style and the possibility to exhibit abroad. Today Ekaterina lives and works in Miami, Florida. She continues the legacy of the innovative technique which she termed synergism. Synergism developed over the decades through the synthesis of two historical trajectories, American AbEx and Pop art and Soviet and Russian avant-garde and nonconformism. Synergism combines collage, painting, and relief from found objects in a symbolic interface which produces a new visual language. Ekaterina builds a material narrative of her life and ideas through very direct and intimate interaction with the objects that go into her works. It is a way to heal the past and work through the struggles of the present. During the pandemic, Ekaterina has created a series of deeply emotional works serving as a catharsis for our historical moment. Her vision for future work is to further explore the material significance that objects play in individual and collective lives by creating a visual narrative, a conversation between objects which bear the significance of this historical moment. In synergism the interplay of texture, color, and symbol act as a medium that accomplishes the work of sculpture, painting, and collage, with the potential to create a sense of home, a container for individual or collective grief, or a place to rest and heal. Ekaterina is a fulltime artist and art conservator.

In your view, what can society to do to best support artists, creatives and a thriving creative ecosystem?

Ekaterina Khromin interview by Alexandra Zavyalova

Introduction:

Ekaterina Khromin comes out of the nonconformist art scene from the turbulent years of the Soviet 80s. She kept the continuity of the movement but brought a transformation into the both intellectual and spiritual thread of visual ideas. A transformation catalyzed by her escape from the threats and repression in the USSR. She arrived in New York in 1990 with her late husband Viktor, and saw the world with new eyes. Today she paints and creates intricate, large multimedia canvases that are in a genre of their own. The genre and method is called Synergism, a combination of different mediums to produce their alchemical result, a sculptural composition reminiscent of relief, with another, quite striking dimension of color bringing the relief to life.

Nonconformist artists were persecuted in the Soviet Union not only for ‘actionism’, but also for painting and holding exhibits in private, in the artists’ apartments most often. In a previous interview with Ekaterina, published in VoyageMIA, we spoke about the cultural shock of her immigration to the United States, and the encounter with the freedom of artistic expression here in the early 90s.

AZ: Could you speak about your experience of leaving the USSR more than 30 years ago now, and what feelings that brings up for you today regarding the state of Russia?

EK: It is always a great feat for Russian immigrants to move away from their homeland, even when the regime is oppressive. It is a great and difficult step to leave behind the land that you love, from the culture to which you belong. It is daring to set off for a foreign continent, having the fear of the unknown that awaits you on the other shore, the uncertainty of finding a job, and a secure living situation.

AZ: I am seeing this important distinction, the love of the land versus the love of the political entity that is a country. Human beings love their land, the land itself. I miss Russia often, the Baltic Sea, the rivers and canals of Saint Petersburg, the mossy Baltic woods, with their familiar trees and berries, that familiar character of the landscape, the village of my childhood summers. It matters less who occupies your land, but more that the land itself is a part of us, and being parted from it is heartbreaking, it is akin to leaving behind your family, your loved ones. It is woven into our biology, and when we leave, we tear ourselves out, but inevitably some roots remain, these parts of us that are forever lodged in the place of our birth.

EK: Absolutely, when I left USSR for New York, I did not want to be a hero, I had to be courageous to save my life. I had no other choice. Being pursued by the KGB, and threatened, I just kept thinking about how to leave, how to escape. I was a young woman with a child, it was very difficult to be brave at that time. I just wanted to be safe with my daughter, not to resist, or fight. It is often undervalued and misunderstood, how difficult it is to be against the government machine, to be a grain of sand against the enormous and faceless force. I fell like a woodchip into the larger current, I didn’t want to protest, I was forced to stand on the side of the protesters. I was terrified of the repressive power of the government.

AZ: What do you mean when you say you were “forced” to protest?

EK: When my late husband Viktor was selling his paintings to foreign buyers, he was followed by the KGB. It was forbidden to trade your art to foreign sellers. I was threatened as well, by association.

One day I was at a haberdashery on the Decembrists’ Street, I used to make clothes and dresses for myself and for sale, and I was looking around, although there was absolutely nothing to buy. And then, not fully consciously, I got the sense that I was being watched. It made me feel really uncomfortable, so I left the store and made my way to the nearby bus stop. I was waiting for the bus when suddenly, someone grabbed me by the shoulder. At first, I got excited, I thought that it was Viktor. I wanted to turn around and laugh with him for sneaking up on me. But I could not turn, a stranger’s voice commanded, “I don’t recommend that you turn around. You have to think about the company of the people that you associate yourself with, especially Viktor Khromin.” When I finally turned there was no one behind me. My knees were shaking and I didn’t know what to do. I looked around to see if anyone noticed but everything seemed to be still, it made me wonder whether this was real. I told Viktor as soon as I got home. He hid his emotions from me so as not to scare me, but I noticed a vigilance rising in him. When we started seeing each other it was the winter of 81, at the time I did not even know who were the nonconformists. We married in 85. I waited to marry him even after we had our first child because I feared the potential consequences.

AZ: Who was this group of people that Viktor was associated with?

EK: The nonconformists were a group of St Petersburg artists, they were mostly of Russian Jewish heritage. In 1975 the Jews started leaving the USSR, and the ones that stayed often would protest. I felt like a grain of sand in the great ocean tide of history and politics and I was swept up in it with Viktor. I was now on his side, and he was protesting, which meant that so was I. The nonconformists became my friends, they and Viktor were doing these illegal apartment exhibits. They made their art with anger, with clenched teeth. At the time didn’t like that they were doing very conceptual and openly political art. For me art was about emotion, I didn’t like that they had to have the political subtext in their art. I did not like how blunt and angry it was.

AZ: But what about men as warriors, standing up to fight, with anger? Anger denotes a boundary to their humanity and their space of expression. When they made the political art, didn’t they try to stand against the regime, like the defenders of their culture, their humanity?

EK: Yes they did, they tried to fight. I understand and respect protest art, but I also understand its contextual temporality. Their art took on a vulgar form. Remember these Lubok engravings, they are always in a sarcastic form.

AZ note:[ Lubok was a style of popular image and text prints from 17c-19c that contained a wide range of themes including satire, comedy, and folk tale elements, sometimes they came in series and could be seen as predecessors of the comic strip.]

EK: It is a folk art that often contains crass language, and images that can at times be very raw and grotesque. I feel like nonconformist art was of that genre, a popular art. So when I moved to the US I did not feel the sense or need to continue making it, it could not exist outside of its context.

But now look at someone like Mandelshtam, his poetry deals with complexity, intricacies of emotion. It is so difficult to take your emotion and put it on the page, to pull it out from your depths.

Leningrad

I’ve returned to my city, it’s familiar in truth

To the tears, to the veins, swollen glands of my youth.

You are here once again, – quickly gulp in a trance

The fish oil of Leningrad’s riverside lamps.

Recognize this December day from afar,

Where an egg yolk is mixed with the sinister tar.

I’m not willing yet, Petersburg, to perish in slumber:

It is you who retains all my telephone numbers.

I have plenty of addresses, Petersburg, yet,

Where I’m certain to find the voice of the dead.

In the dark of the staircase, my temple is threshed

By the knocker ripped out along with the flesh.

All night long, I await my dear guests like before

As I shuffle the shackles of the chains on the door.

1930* [Poem was censored for being anti-soviet]

In this poem, Mandelshtam refers to the political and social atmosphere, there is no direct reference to the politics or his position, but these things are still evident.

AZ: His poetry seems to resonate with a more extended time because it doesn’t rely as strongly on the very particular, almost memetic elements that conceptual art of a specific timeframe does.

EK: If you take for example the art of Komar and Melamid today, their work is not about emotion, it is explicitly political, dealing with evocative images.

AZ: The Sots Art (Soviet Pop Art) of Komar and Melamid and nonconformist art sometimes evoke the emotion of aggression, in active or passive form. And then there is punk, rap, and rock&roll which is relevant in the contemporary context with bands like Pussy Riot bringing attention to the extremes of current Russian hegemony. Within these genres, the poetics are more blunt. Punk found its origin in the working class in Britain, Rap originated in the black culture both coming from institutionally marginalized communities. In Russian pop culture today there are artists like Pussy-Riot (punk), Aquarium, FACE, and many others that show this aggressive response to the current events.

EK: You see, Pussy Riot, these young women, how easy it was for the Russian government to send them to the labor camps. I was a girl just like them. That was me. A young woman against the machine.

Today these artists, like Shevchuk too, for example [stadium crowd gathering rock singer after anti-Putin remarks was forbidden to perform], send some kind of a message, a cry for help.

Many of the nonconformists who immigrated ceased to be artists, poets, writers. The political genre only exists in its distinct time period and disappears after the theme becomes irrelevant as a reflection of the changing times. And these new political movements in Russian art today will also cease to exist, unlike the art that touches the spirit, a deeper vein of the people or humanity. What I am trying to say is that I never wanted to continue political nonconformist art when I immigrated to the United States.

What was astounding, Viktor and I did not make paintings of protest, but the style of expressing inner emotion is not realism and that was enough to label it as nonconformism. My inspiration was drawn from artists like Filonov or Petrov-Vodkin. Today, my painting along with one of Viktor’s hang at the MEAD museum where in their large Russian art collection you can also find Filonov’s Family and Petrov-Vodkin’s, Petrograd Madonna.

We often hear about learning lessons – but just as important is unlearning lessons. Have you ever had to unlearn a lesson?

AZ: How does your art respond to this particular moment in time? EK: My art is more tender, it deals with deep and complex emotions, and it dives to the bottom of the self. I have to navigate a very nuanced and tangled field of my own background. I am neither Russian nor Jewish, I am stretched between two cultural fabrics, and I don’t fully belong to either. This is the lens through which I am watching the current events between Russia and Ukraine. What is happening today fills me with so much grief, as I have dear friends in both countries. I feel as if some force is trying to pull me into this political mire, while I am going within myself and trying not to define my experience by chopping it up into blunt blocks.

I became a truly independent artist after I moved to the United States. Independent of the State ideology and the influence of the nonconformist art group. I remember at my residencies in the Soviet Union I was always pressured to do more realistic art. My instructor kept saying, in a patronizing tone, that women were best at painting something from life, still lives, or landscapes. Women were second-rate citizens even in the arts. But I was most happy when I painted abstract interpretations of music, or expressive compositions, inspired by Mark Chagall. Though I was drawn to Chagall not just for his composition. I was drawn to my Jewish heritage, indirectly, through his work.

Today, I still refuse to paint realistic, blunt, and obvious subjects. No matter the pressure I feel to be more legible in the world then and now, I will always continue to explore the more complex and provoking existential states in my work, as well as less comfortable subjects.

Interview conducted in August 2022

* Translation by Andrey Kneller

Contact Info:

- Website: http://ekaterinakhromin.com/

- Instagram: @katerinakhromin

- Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/katerina.khromin

- Twitter: @KhrominArt

Image Credits

Photographs of the artist: Ekaterina Khromin in her Studio Painting1 Peacemaker, 2022 Painting2 War, 2022 Painting3 Rememberance in Red 2021 Painting4 Masks of Transformation 2021 Painting5 Unifying Web 2021 John A. Verner – Clear Lotus Photography