We caught up with the brilliant and insightful Edward Mccormack a few weeks ago and have shared our conversation below.

Edward, looking forward to hearing all of your stories today. We’d love to hear the backstory behind a risk you’ve taken – whether big or small, walk us through what it was like and how it ultimately turned out.

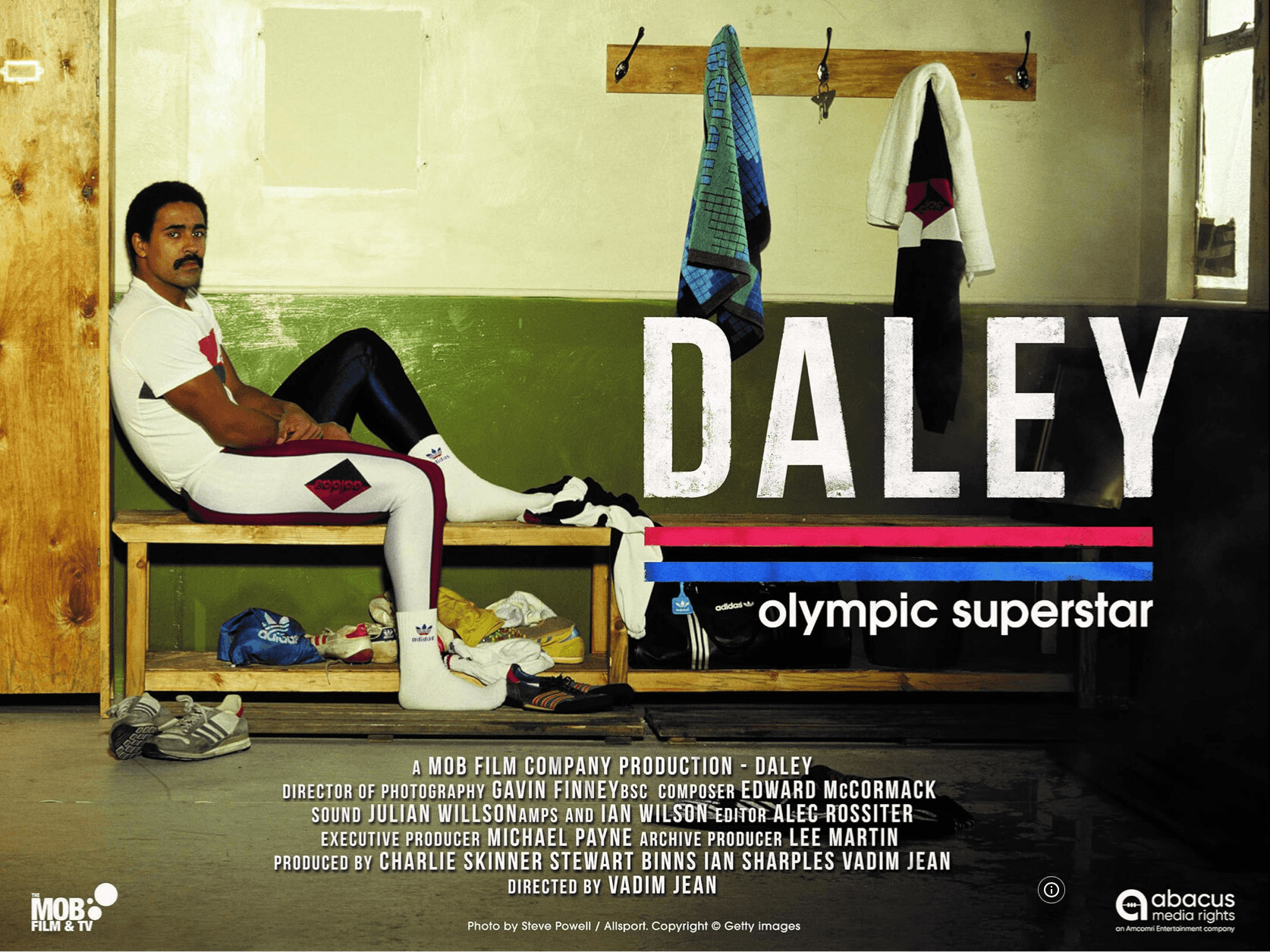

My phone unexpectedly rings at 3AM as I’m sleeping in my small Harry-Potter-style studio appartment (staircase above my bed and all). The call is from David Buckley, my friend and legendary composer whom I assisted for years prior to his move from Los Angeles to Andorra (hence the 3AM phone call). He tells me that he was hired to score an Olympics documentary, and had planned to start scoring it eight months ago. However, he has still yet to receive a cut! Apparently, the production schedule has been pushed so drastically that there is now only one (!) month’s time left before the airing deadline to score the approximate 78 minutes of what he describes as “sophisticated John Williams-style brass fanfare music with a dash of 80’s synths”.

With all of the other projects he has going on, Dave is naturally intending to quit the project, as the deadline has made this job impossible. However, since he knows that I specialize in “John Williams’ style” orchestral writing and storytelling, he offers to put my name forward to the director (Vadim Jean) as a replacement.

Talk about a difficult decision – I’m completely torn between the intense desire to seize this breakthrough opportunity I’ve been waiting for my whole life and what seems like certain doom because of the impossible deadline. However, it doesn’t take me long to realize that I’ll likely hate myself for the rest of my life if I don’t take what could be my only chance ever to break into the industry. But yet, I still can’t bring myself to say yes to something where I know with 100% certainty that I’m going to fail. If it wasn’t for Dave’s conviction that it’s within my capacity to finish in time and that the risk is worth it, I would ultimately have said no. But unfortunately, he talks me into it. Making peace with my impending death, I make the phone calls to secure the project. I’m now officially the composer to have his career beheaded by the guillotine that is Daley: Olympic Superstar. (And of course, I thank Dave “times infinity” for the beheading opportunity.)

As I’m sealed off from the world in my home studio, the days and nights of scoring are inhuman. The number of hours each day that I have to work at the bleeding edge of my capabilities is unprecedented, suicidally miserable and visibly unhealthy. Even with the miraculous three-week extension that pops up halfway through, there is still no way in hell that I’m going to finish. Because when taking revision requests into account, the math requires me to write 3 minutes and 12 seconds of extremely difficult orchestral music each day, but I was forced behind that schedule by a month at the outset! However, in the middle of a particularly miserable day, a lightbulb goes off: I realize that my working window didn’t include the week of the dub. Since they will only be dubbing through about 15% of the film each day, there’s no reason why I can’t deliver cues throughout that week on a rolling basis, just in time to be dubbed. After running the desperate idea by the director, he reluctantly allows it. While I am by no means even remotely out of the woods, the math, by sheer dumb luck, now ends with a “0 minutes left” on the very last day of the dub. By dub week, I’m an emaciated, feral animal sustaining itself on instant protein shakes, clawing its way though shard-covered minutes of music. With 4 hours left on the final day of the dub, I turn over my last 3 minutes of music, and then collapse on my bed.

Weeks go by without hearing a word from Vadim or anyone on the team. The director Vadim clearly hates my score. And I can’t blame him; the chances of worthwhile score emerging out of those working conditions were the same as immortality’s solution emerging out of Chipotle’s secret menu. But then, Vadim calls me up randomly one night as I’m cooking dinner in my house-elf-sized kitchen. “Oh man, here it comes,” I think. I prepare myself to hear that they’ve replaced my score with stock library music to save the project, and then answer the phone. However, instead of hearing his usual greeting, I hear a roaring applause from a packed auditorium. It turns out that Vadim has called me from the stage of the theatrical premiere during the Q&A, and the 300+ sold out, star-studded audience is applauding me for the score; I’m completely speechless. (Which is a problem, because moments later, Vadim simply says, “Ed, you’re on speaker”, implying that it’s my turn to say something. Talk about being unprepared for a thank you speech – my tofu is burning!)

Incredibly, the project turns out to be “this summer’s quiet hit” according to Athletics Weekly. With an 8/10 rating on iMDB, it ends up being the most highly rated project in the director’s 30-year career! Immediately after the release, hundreds of raving reviews seem to keep flooding in. Even the BBC itself makes a point of publicly calling the score “brilliant”! The fact that this Olympics documentary was deliberately released in sync with this year’s (2024’s) Olympics likely contributed to the unusually large number of reviews and expansive viewership, leading to the doc winning “Most Successful Sports Broadcast” at this year’s Sports Business Awards. What blows my mind the most is that of all the documentaries the BBC released this year, they have chosen mine to be put forward for a BAFTA Television Craft Award this year for best original music (“factual” category). You’re not supposed to be considered for a major industry award on your first project ever! On the contrary, this project was a sinking ship that was supposed to end my career. But instead, it’s turned out to be an “in your dreams” good breakthrough gig!

But at the end of the day, I was successful only because I took an insane, (and really, idiotic) risk and got very, very lucky. At the same time, I’m extremely grateful to Dave, Vadim and sheer dumb luck for giving me a breakthrough opportunity that so perfectly matched my skill set. However, I would absolutely never, ever do it again. That said, I’m thankful that it happened (and even more thankful that it’s over with).

Awesome – so before we get into the rest of our questions, can you briefly introduce yourself to our readers.

Well, my entrance into the industry starts as I’m traveling west, kicking up dust at 60mph with my piano keyboard, dorm bed sheets, and five Asians in a Cruise America RV (which, if you’re not familiar, is basically a full-size four-door milk carton). All recent graduates, we are taking a southern state cross-country road trip from Boston to LA, hitting all of the major sites along the way. But while it might seem like I am traveling light, I have a lot more intellectual baggage stowed away:

Before college, I had studied over 10 years of classical composition and piano performance with Juilliard graduates. Then, I attended Berklee College of Music in Boston, where I had the fortunate opportunity to complete 4 majors and 2 minors in 5 years, graduating Summa Cum Laude with a 3.981GPA. As college side projects, I studied classical composition with a Harvard teacher on the weekends, Medieval music remotely with a professor from Indiana University, and I invented a new music theory and codified it in two volumes spanning 360 pages. Over those 15 years, my teachers were students of Elliot Carter, Dmitri Shostakovich and Leonard Bernstein. In other words, I was a total douchebag.

So, we arrive in LA and settle into our shared two-story 5 bedroom house in Huntington Park. Confident that my education is going to make me uniquely valuable, I walk straight up to some of the biggest studios in LA and apply for assistant positions. Sure enough, I land my first internship – a running position at XYZ studios, whose multiple rooms are spectacularly decorated to recreate famous ancient places from diverse countries around the world. However, after 3 months of working around the big names here, I still find myself in the lowest position on the respect totem pole. Most days, I stand “on-call” off to the left side of the mixing console while the head engineers work hands-on, make all the decisions, and ignore me. My biggest hand-on contribution is making coffee. It turns out that while my education is uncommonly unique, nothing has made my actual output uncommonly special to a degree where I am valued for it. And thus, I’m forgettably redundant.

This depressing realization couldn’t have come at a worse time in my life. Because as I make my engineer’s 4th cup of morning coffee today, I don’t realize that my mediocrity is caused by more than just my external performance. In actuality, a long-standing personality flaw – one that somehow survived the maturation machine of college – is preventing me from resolving this newfound career crisis:

One of my most embarrassingly immature habits is convincing myself that I know exactly what others are thinking. (FYI, they are almost always highly dramatic stories. But the best part is that they are never, ever correct.) However, the problem is that the stories I tell myself are so powerfully detailed, realistically deep and overwhelmingly convincing, that when I relay them to close friends to be told why I’m wrong, they instead almost always agree with me (reinforcing my own belief). I even tried a therapist once to see if he could fix my delusional habit, but I ended up quitting after the first month; he believed my stories too. Even worse is that the more I like someone or something, the more elaborate my stories become. Consequently, these stories begin to take over my perception of the world. And eventually, I start acting on them. The end result? [Cue “Creep” by Radiohead.]

Realizing my job at XYZ studios is going nowhere, I walk out the ancient Egyptian front door for the last time at 5PM rush hour and head back home in the knowledge that I’m a failed intern. Sitting stuck in traffic, all I can think about is how I clearly need to make my education work harder for me. Taking the advice of a mentor, I get home, print out 50 of those tear-tab fliers advertising myself as a film composer, go to USC campus, and start taping them all around the film department. But as I am hanging fliers in those tan, empty hallways while trying to avoid being caught by the janitors, I run into a film student named Brittany. She turns out to be the producer of a popular student TV show. After learning that I’m a film composer, she introduces me to her director, Chris. Chris and I quickly hit it off, and a couple hours after sending him my education portfolio, he’s asks me to score his short film. A new opportunity to solve my career crisis has just landed in my lap! However, instead of feeling relieved, I feel anxious and stressed under the pressure to perform at a level that I literally just failed to achieve at XYZ studios. My failure there quickly reminds me that I’m not actually good enough to meet this director’s expectations. And so, this realization that he’s actually just hired me suddenly fills me with a sense of dread. While I’m determined to resolve my career crisis with this project, I can’t ignore the statistical likelihood that this isn’t going to end well.

That night, I sit at the top of my blow-up mattress with my college-issued laptop as I anxiously but eagerly open Chris’ email containing the video download link. However, I immediately run into a problem: After watching the film through a few times, my first reaction is nagging uncertainty. Because while there is a clear overarching story, there are so many glances, movements, body language ambiguities and secondary decisions that don’t have clear explanations. Obviously, I can’t score scenes that just don’t make sense! And I can’t stop thinking about them all night. Three hours in, this project has already come to a grinding halt.

Instead of starting to write the next day, I end up spending weeks taking long walks on Planet Fitness treadmills mulling over what everyone in the film is thinking, why they are thinking it, and why they make even the smallest of movements or facial expressions. Obsessed with making sense of these details, the story now occupies my mind 24/7 like a thick daydream, demanding precedence over important daily activities. Eventually, it becomes so all-consuming that I involuntarily adopt the attitudes and ideologies of the characters in my film, and I start interacting with supermarket cashiers and friends on phone calls in ways that reflect my new perspectives. But then one day, everything clicks. Finally, I have convincing explanations for all of the story’s intricacies and can begin working with clarity and purpose. Now starting almost two months later, I throw myself into the work, composing day and night to transmit every nuance of the story with incisive score. I find myself making hundreds (!) of compositional decisions over the course of this 17-minute short film – each one absolutely necessary to bring out the deep and detailed story I have come to understand.

However, reality eventually did take back over, and the sobriety was horrifying. Because finally, the 7:30AM Sunday deadline arrives, and I suddenly realize that I’ve spent the last few months going completely off the rails on this director’s short film! In the cold light of day, my score is this grotesquely complex explosion of noise that sounds like the Minions had got hold of GarageBand. And worse, there is no time to fix it. At that moment, I realize that I’ve just blown up another opportunity to prove myself uniquely valuable. Worst of all, I’ve just proven myself unemployably bad. As I slouch uncomfortably in my bedroom studio to avoid the unwanted Lasik being administered through my blind-shades, I hit send on my laptop, knowing it will be the last thing I ever send to this director.

20 minutes later, the call to chew me out lights up my phone. I’ll never forget Chris’ reaction: “Uh, this is…. incredible. Seriously, I have never heard anything like this. My mind is blown right now. I just can’t believe how good my film is. Great job!” I’m completely shocked. Those words are so unexpected that they’re almost abrasive against my ear drums. Incredibly, all of my detailed scoring work has translated. It isn’t just noise. The director gets everything – every last detail – that I implemented with narrative intention. And most importantly, he loves it! Chris’ reaction properly stuns me. It isn’t just relief – it’s the realization that someone else has, for the first time, truly experienced the world as I and my delusional brain do (even though it’s the imaginary world of this film). In this moment, I feel one of the most unexpectedly powerful human connections I’ve ever felt.

It wasn’t until years later that I understood the importance of this moment: Without realizing it, my embarrassingly immature delusional thinking habit, not my education, has just made me uniquely valuable. Where my powerful education had failed, it is my pathetic delusional habit that resolves my career crisis. It was the key to unlocking my signature voice that no amount of formal education could provide.

And after 10 years of unknowingly repurposing my delusional thinking habit to serve my film scores, the result is a bizarre, unorthodox, and just plain weird approach to storytelling that has come to define my artistic brand as a professional film composer. In clinical terms, my style is characterized by orchestral scores that are in constant flux, changing style, orchestration and tempo at speeds that most composers deliberately avoid. However, in my approach, these rapid changes are done in a way that avoids feeling jarring or “Micky Mouse-d”. Rather, they feel, as a director once put it, “obviously correct”. But aesthetically, my style is defined by the vast amount of narrative information that the score adds to the script. This thick extra layer makes the film feel richer and longer than it actually is. Most importantly, this amount of persuasively accurate emotional information creates a deep level of audience empathy with the onscreen characters, which in turn creates a uniquely intense immersive experience.

Ultimately, I will never be thankful for having developed such a stupid thinking habit – it’s ruined too many things. But, it’s nice to know that the thousands of hours spent thinking about the thoughts of others wasn’t a complete waste of time and energy (arguably unlike my education).

How about pivoting – can you share the story of a time you’ve had to pivot?

I’m sliding into my Ikea desk with 4 computer screens as I expectantly stare at the participant window in Zoom. In about 120 seconds, I’m going to be speaking with a junior agent at one of the biggest film scoring agencies in the world. This is my shot at getting signed and launching my career. And I need to get signed, because I need a way to pay my rent after having left my assistant position two months ago. The calming magnesium l-threonate I took a half an hour ago should be kicking in by now, and for the first time in years, my veins don’t contain single a drop of caffeine. My responses to most likely questions that I’ve spent two weeks preparing are memorized cold, and I feel confident I’ve done everything I can to not have a panic attack. “Ding-ding”.

The short, red curls that cover my screen lean back to reveal Nathan, a fit 40-something who’s the likable kind of bro. I say hello, and the conversation begins. Things are off to a great start! Small talk is lively as he takes his laptop and kombucha to his kitchen table. Then comes the very first question that’s asked in a way where you know the real interview is starting. “So, tell me about yourself.” I know that one. “Sure! I first got into music when…” But as soon as I start to answer, a terribly familiar self-awareness starts watching me from about two inches behind my eyes. Suddenly, the faucets of anxiety, panic and terror start running. Now, the way I feel about getting to the end of this prepared response feels the same as getting to the other end of a tight rope stretched across the Grand Canyon on a windy day. I take two steps into that sentence. Then, my heart rate starts skyrocketing. I kept pushing through the words, but as my heart rate increases, I start hyperventilating. I can’t breathe. My face turns red. My throat jams tight and heavy like it’s clogged with dry bread. The worst was happening. Mid sentence and without missing a beat, I quickly say, “Can you excuse me for a sec?” As I’m already half standing from my chair, he looks at me with wide eyes and says, “sure”. I react to “sure” like an Olympic sprinter reacts to the starting pistol. Now, as I stand six feet off to the left of the camera trying to recover, all I can think are two things:

1. How the hell am I going to make it through this?

2. I fucking hate myself.

When I come back, I pick up right were I left off without any segue – talking at 100 miles an hour until I finally reach my last sentence (which was miles away from what I had memorized.) He hesitates, and then simply says, “Well. Thank you. That was really interesting learning about you.” To his credit, he then carries the rest of the 30 minute interview’s conversation, stopping every now and then to ask me questions that require only 2 to 3 word answers. I’m thankful, because it allows my panic to drop to anxiety and eventually down to merely awkward discomfort. But, the conversation is no longer the fun hang that started our zoom call. It’s now formal, cold, and uncomfortable. Finally, he makes his closing remarks: “When I’m considering signing composers, I never listen to their music first. The first thing I need to determine is whether or not I can put them in a room with a director and make that director feel good.” Then, he simply says, “You’re not ready for an agent yet.” And then, we part ways. I shot my shot, and the misfire splattered my hopes across multiple white walls. Door closed. Because I have failed, my career is about to change. With rent unsorted and now without any composition prospects, I’m forced to accept the fact that I need to find a non-music job to pay my bills.

A couple days later, I’m finishing moving my car in my neighborhood’s monthly squid game called “street sweeping”, where the loser gets the spot with falling leaves and those who don’t participate go bankrupt from parking tickets. As the first leaf hit my windshield, my phone rings. A life insurance company has found my online resume. Ten minutes into the call, they offer to hire me, and I instantly feel the euphoric rush that only paycheck-to-paycheck-er’s can understand of having solved this month’s rent. But, that euphoria ends immediately as soon as she describes what I would need to do: My job would be to give hour-long Zoom presentations to strangers all day long. “Of course!” I think. “The very thing I’m so bad at that it just ended my film scoring career is the thing I’m being asked to do.” But, seeing as I didn’t have a choice, I take the job.

The next day, I pull up into my desk in a collared shirt for my first week of training. “A client will buy you before they buy an insurance policy,” my manager says to all the trainees on the Zoom call. “Welp, I’m screwed,” I think. Because in addition to the emotionally brutal 200 daily cold phone calls I’m forced to make, I have to practice presenting the hour-long “Union Benefits and Life Insurance” presentation to my manager. My time comes to give it my first go: “Hi,” my voice shaking, “my name is Ed McCormack from OPEIU Local 1077, and I’m here to administer your benefits today…” I make it to about the third sentence before my panic attack stops my lower jaw from forming words. “She’s clearly going to fire me,” I think, as I wait for her to say it.

But instead, my manager is both understanding and encouraging, and tells me that this is a common problem amongst new insurance agents. I am surprised, relieved and grateful. We eventually develop a system where I start doing live presentations with real clients, where if (i.e., absolutely, positively when) I choke up, she takes over the presentation for me in a way that feels like it’s an intentionally planned handoff. (My manager is the best.) Seeing how far I can get before choking up eventually takes on the thrill of extreme sport risk-taking, like I’m a skateboarder seeing how long I can nose grind before catching tip. But eventually, I make it through the entire first 25% of a presentation! It’s a huge accomplishment for me. But then 50%. And then 75%. And then one day, I give a full presentation without my manager saying a word, which ends in a sale that makes my manager $1,800. While I know I owe her every penny, I still can’t help thinking, “Bitch, you stole my money!” However, the confidence of that success instantly melts to terror. Because the very next day, I’m graduated into the field as a solo agent.

My sky diving instructor was now no longer strapped to my back, and my gamified fear immediately reverts back to feeling existential. Terrified, I roll into my desk, and make my first solo cold call. However, despite my fear, my phone skills are now so good that I can get even the toughest cookie to show up for an appointment. By my 8th solo week, my presentation skills are now so strong that I am landing huge sales. But then one day, the branch manager calls me out during one of our weekly branch Zoom meetings. As I’m listening in disbelief in my Polo shirt and plaid pajama pants, it turns out that I have achieved an 87% sell rate, one of the highest in my entire branch. And after just the first few months, I’ve apparently sold over $68,000 worth of business for the company! I quickly become known as one of the best insurance agents in my branch.

For me, this is unreal. Because I’m the guy who has panic attacks. I’m the guy who’s social anxiety is so crippling that it destroyed his film scoring career, crucifies budding relationships and repels people like a Thanksgiving-weekend dumpster. That guy can never win when the name of the game is, “A client will buy you before they buy an insurance policy.” And yet just yesterday, I sold a woman from Westwood a record-breaking $948/month plan (the day after which she canceled after speaking with a different follow-up agent, since I wasn’t available.) And by the end of each presentation, the often cold, skeptical strangers that I meet at the beginnings of calls become playful, relaxed acquaintances with whom I have report. They exude a warmth and interest that is genuine and unintentional, and flash smiles that are way too big for the amount of money I’m taking from them. For the first time in my life, I feel like a worthwhile person that people actually want to be around.

However, as I was sitting at my desk in disbelief of my branch manager’s words, I could never have anticipated the phone call I received at 3AM that same evening: David Buckley, the legendary film composer whom I assisted for years, tells me that he is unable to score a major project, and offers to put my name forward as a replacement. Of course, I immediately said yes. (Sorry insurance, but you always knew you were #2.) However, after relaying my interest, Dave tells me that the director wants to Zoom with me, so he can get a feel for whether or not we would work well together. The pain of my old failure with the film scoring agency pulls on the pit of my stomach with surprising freshness. My film scoring career had failed precisely because Nathan didn’t feel I would be a good hang with directors. He knew I wasn’t ready. But right now, that is exactly the person I need to be in order to get this gig.

An hour later, I’m once again staring expectantly at the participant window in Zoom 120 seconds before the call begins. I’m just as nervous as I was for Nathan. But this time, instead of thinking about what I’m going to say to this director, I start reciting with confidence the opening words of every successful Zoom call I’ve had this month: “Hi, my name is Ed McCormack from Local 1077, and I’m here to administer your benefits today…” “Ding-ding.”

45 minutes later, after the most confident, fun, mutually enjoyable conversation of my life with a complete stranger, I’m hired for my breakthrough gig as a film composer. At that moment, I realize something important: When I pivoted out of film scoring into insurance, I didn’t actually pivot out of film scoring at all. Instead, I simply switched to practicing my weakest film scoring skill that had been holding me back this entire time: my ability to be relaxed and confidently myself around people that matter to me.

Sometimes on days with particularly successful meetings with film clients, I look back on panic attack and anxiety disasters and think, “Dang. If only they had met now instead of then, that might have turned out differently.” And those are the best moments for me, because it’s evidence that I’m better than I used to be. Don’t get me wrong – I still have panic attacks, and I still am socially anxious. But, these instances are much less frequent and usually way less severe now. While I still have a long way to go towards making this skill consistent and reliable, that insurance pivot gave me two things I thought were impossible: a clear direction for how to get there, and proof that I’m capable of achieving it.

Can you share a story from your journey that illustrates your resilience?

When I walked through the door of his small, vine-covered guest-house-turned-recording-studio on my first day of work, my first-ever boss Stan was hunched over the mixing console rubbing his swollen, sweaty furrows. “Sit down”, he says in a cold voice, barely looking at me. Only after 5 minutes of silence did we start to talk. I learn that Stan has been married 5 times, and has just finished wrapping up a divorce. No wonder he’s stressed. “Oh man, that’s a rough ride. I’m sorry,” I say. “Ah, thanks. Though it’s all water under the bridge now, because the love my life and I are getting married next weekend! By the way, did you see Whiplash yet? That chair throwing scene – so inspiring!” Oh Stan. But I like him. He’s brutish but honest, harsh but sincere, passionate but a chair-throwing sympathist. Through that raw interface, I immediately feel a connection with him, because I instinctively know that I’m meeting my first important mentor out in LA.

Throughout my first week, Stan and I talk about my immediate career goals. When I tell Stan that I am looking for a job as a runner at BEETS Studios, he callously says, “Ha! They’ll never hire you in a million years. You’re not good enough yet.” Professor Snape strikes again! I wouldn’t trade his searingly honest assessments for the world. Unfortunately, that extremely valuable insight wasn’t exactly well timed; he didn’t know that I’ve in fact already landed a job interview with BEETS, which is scheduled for this evening. Pep talk aside, I was determined to give the interview my best shot.

So, I walk through towering red doors of BEETS Studios hoping for the best but knowing that I’ll be told I’m under-qualified. However, incredibly, the interview goes really well, and they want to hire me immediately! I can’t believe it! And I can’t wait to tell Stan about my success. The next morning, I walk into Stan’s studio and break the news. “Oh really. Huh,” Stan says with a disappointing lack of interest. But still, it feels good to hear him at a loss for criticism for once; it’s the biggest compliment he’s ever given me. However, that was the last time I felt happy for a while.

The next morning as I am eating breakfast in my Huntington Park appartment, I open my email to find that BEETS Studios has sent me a follow up email. The email simply reads, “Due to internal resources, we are no longer able to hire you. We wish you the best of luck!” WHAT??! Even my Raisin Bran gasps in confusion. It makes absolutely no sense, and I am immediately overwhelmed with disappointment. I can’t stop thinking, “What in the world happened?” Even worse, I’m dreading the moment when I’ll have to break the news to Stan today. After having told him about my breakthrough success just yesterday (feeling good that I had proven his estimation of me wrong), I now have to tell him how it’s all fallen apart for reasons I can’t understand, and that he was right.

That morning, I walk through Stan’s door and break the news. “What!”, he half-shouts, “Don’t worry about them. They were never a good fit for you. I knew that since yesterday. I said that they’d never hire you, because I didn’t want you there. I wanted you to work somewhere else – I’ll make sure you get a solid job at Capitol Records where I already knew you’d do much better.” Something is off. The wry smile that started his reaction came on way too quick. He looks uncomfortably warm. He’s unusually docile. Unusually fidgety. Unusually nervous. I can’t believe my eyes; the guilt he’s displaying is unmistakable.

I’ll never forget that moment as I’m standing in front of him in my 5-dollar v-neck looking down at his leather shoes. I feel like a 12-year-old scrawny kid pinned down by an 800 pound silverback gorilla. Because in that moment of suppressed rage and disbelief, I learn in that exact, precise second that I am no longer in school; suddenly I find myself in the jungle where might is right. I had threatened a gorilla’s place as the alpha male by demonstrably contradicting his opinion, and I got my arms pulled off. It was one of the most important lessons I’ve learned in LA: No matter how capable you are, don’t work in a way that puts you into direct competition or comparison with those higher up than you. Because while you might know better or have the ability to surpass them and do a better job, they have the time-earned networking muscles to rip your arms off to make sure that never happens. In that moment, my naive view that people are fundamentally good and want to see others succeed is shattered. On the contrary, some people not only don’t want others to succeed, but will actively prevent them from succeeding if it challenges their sense of status or self-worth.

Needless to say, I quit that day. Thankfully, Stan’s actions give me the most functional piece of advice I would ever learn from him; start networking. And that is exactly how I bounced back to ultimately have the career I have now. While I’m still naturally drawn to understanding people I meet as fundamentally good, this experience has helped me to temper that instinctive sentiment with a healthy level of caution that requires “proof of concept”.

Contact Info:

- Website: https://www.edwardmccormack.com

- Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/edwardmccormack_music/

- Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/profile.php?id=61564145910588

- Linkedin: https://www.linkedin.com/in/edward-mccormack-a2593a42

- Twitter: https://x.com/EdwardMc_Music

- Other: Spotify: