We recently connected with Dr. Jennifer Tien-Lo Young she/rs and have shared our conversation below.

Dr. Jennifer Tien-Lo, thanks for joining us, excited to have you contributing your stories and insights. We’d love to hear the backstory behind a risk you’ve taken – whether big or small, walk us through what it was like and how it ultimately turned out.

Since the first time I studied abroad as an undergrad at University of California, Irvine, I have looked for ways to work or study outside of the U.S. I have been fortunate to find many opportunities. In one of my early-career sojourns in the early 2010s, I participated in a short-term immersion program in a country in Southeast Asia. The program was led by two male professors who are White cis-men. Combined, they had extensive experiences living and working outside of the U.S. and they created a dynamic exchange program with a major university in the host country. The program was filled with impactful experiences such as exchange with host country university students studying psychology, visiting places with historical and cultural significance, and engaging in an intensive group therapy practicum with host country students.

One of the professors was displeased by my suggestion and immediately began to manage the exchange as though I was derailing it somehow. It was mortifying. What he did not know was that some of the host country students later shared their appreciation of that exchange with me. They described feeling empowered when asked to use their own language. Some concluded that I understood because I am also Asian. At that time, as an early career professional, I was filled with uncertainty and reeling from the message that I had done something wrong. So I just smiled politely.

Today, I see what happened with more clarity. And while I do agree that citing sources and teaching concepts accurately is obviously important, I proffer that the consideration here was about empowerment in the praxis of learning. The minuscule action taken in that moment challenged the colonizing power structures that existed in that room, in education, and in many other settings. It is a moment that would return to me years later whenever I was sent overseas to facilitate trainings to foreign nationals. It informed my approach and served to remind me of the power dynamics that exist in any seminar, training, or workshop and what can be done to empower, not oppress.

Dr. Jennifer Tien-Lo, love having you share your insights with us. Before we ask you more questions, maybe you can take a moment to introduce yourself to our readers who might have missed our earlier conversations?

To say that I had a calling to work in the field of psychology sounds cliché but it is true. When I was 10 years old, I supported a friend who disclosed to me that they were a victim of sexual assault. With what little I knew at that time, I was somehow able to intuit what this person needed to feel safe and less alone. From that moment on, my life was dotted with a plethora of experiences where I found myself in a supportive role. In high school, I was even taken out of class and called to the principal’s office to support two of my peers in conflict. Naturally, I considered other career paths: advertising executive, attorney, professional background dancer. But, in the end, my nature won and I followed its lead.

Decades later, I am running my own private practice providing psychotherapy to the general public. My work is focused on helping folks heal from adverse and/or traumatic life experiences, which most people will have at some point in their lifetime directly or intergenerationally. While my clients will see the face of an Asian woman, my identities go beyond the visibility of my race, ethnicity, sex and gender. Because of my life experiences, I identify as a multicultural a global citizen. I’ve had the pleasure and privilege of living, studying, or working in several different countries spanning across six continents. For that reason, a lot of my work has been around supporting Third-Culture Kids/Adults, global nomads or transnational people, humanitarian aid workers, and expatriates.

In my practice, I regularly reserve spots for pro bono and reduced fee therapy to those who are under-resourced or underemployed. I work with groups like Grow Restored Foundation which provides scholarships for those who need supplemental income in order to afford the cost of therapy, while also doing away with the expectation that psychology practitioners work for less than what they deserve.

As a professional and human, I strive to remain a student. I believe expertise is overrated and dangerous for continued learning and authentic connection. I strive to be an ally. I strive to be anti-racist. I strive to dismantle oppressive structures. I strive to live by the Golden and Platinum Rules. I strive to act with integrity, treat all people with dignity, and connect with people from everywhere.

How about pivoting – can you share the story of a time you’ve had to pivot?

Although I was providing teletherapy for years prior to the COVID 19 pandemic, it was the pandemic that led me to transition completely to teletherapy. The adjustment from meeting clients in person in a comfortable office to meeting on a screen for hours every day was challenging to say the least. During a time when people were feeling scared and isolated, it was difficult to be unable to sit in a room together and provide a haven for safe, in-person interaction. Therapists all over the world had to quickly learn how to provide a sense of safety and create a virtual space that cultivates connection in a two-dimensional format. It was exhausting.

To get through it, I leaned on my professional community. Around the time COVID 19 made its way to the U.S. in March 2020, I was in the process of arranging meet-and-greets with therapists who identify as part of the Asian diaspora. It was strange to meet colleagues for the first time and not shake their hands and converse with masks on. Days later, everything shut down and all subsequent meetings were conducted virtually. In short order, our group of four tripled and we found ourselves meeting twice a month. While some meetings focused on professional consultation, other meetings were centered around addressing Anti-Asian hate, which was brought to the surface with the pandemic. Some of us had experienced verbal and physical assault. These meetings were a part of self-care. They showed me how vital it is to have community and solidarity. Pivoting my business practice to adapt to the significant changes the pandemic required and maintain my own mental health became a lot easier with our community.

We often hear about learning lessons – but just as important is unlearning lessons. Have you ever had to unlearn a lesson?

In my profile for Inclusive Therapists, I write that “therapy is new, healing is ancient.” During my training and internship years, talking to clients about having a yoga asana practice would have attracted skepticism. At that time, meditation had only just creeped into the mainstream and a practice called “mindfulness” was gaining popularity.

In the U.S., these practices used to be referred to as “alternative methods” of healing, much like acupuncture was just over a decade ago. Today, these methods are well known and often prescribed to patients by mental and medical health professionals.

While the U.S called them “alternative,” they were simply known as healing to many parts of the world. It was not until it was researched in the U.S. that they were legitimized as practices and gained popularity worldwide. I had to unlearn my own assessment of what was a legitimate healing practice. While the scientific method is a vital part of our practice of psychology, it takes time for science to prove something. That does not mean that the wisdom that exists, sometimes for centuries, in other countries and regions of the world are inferior or to be dismissed.

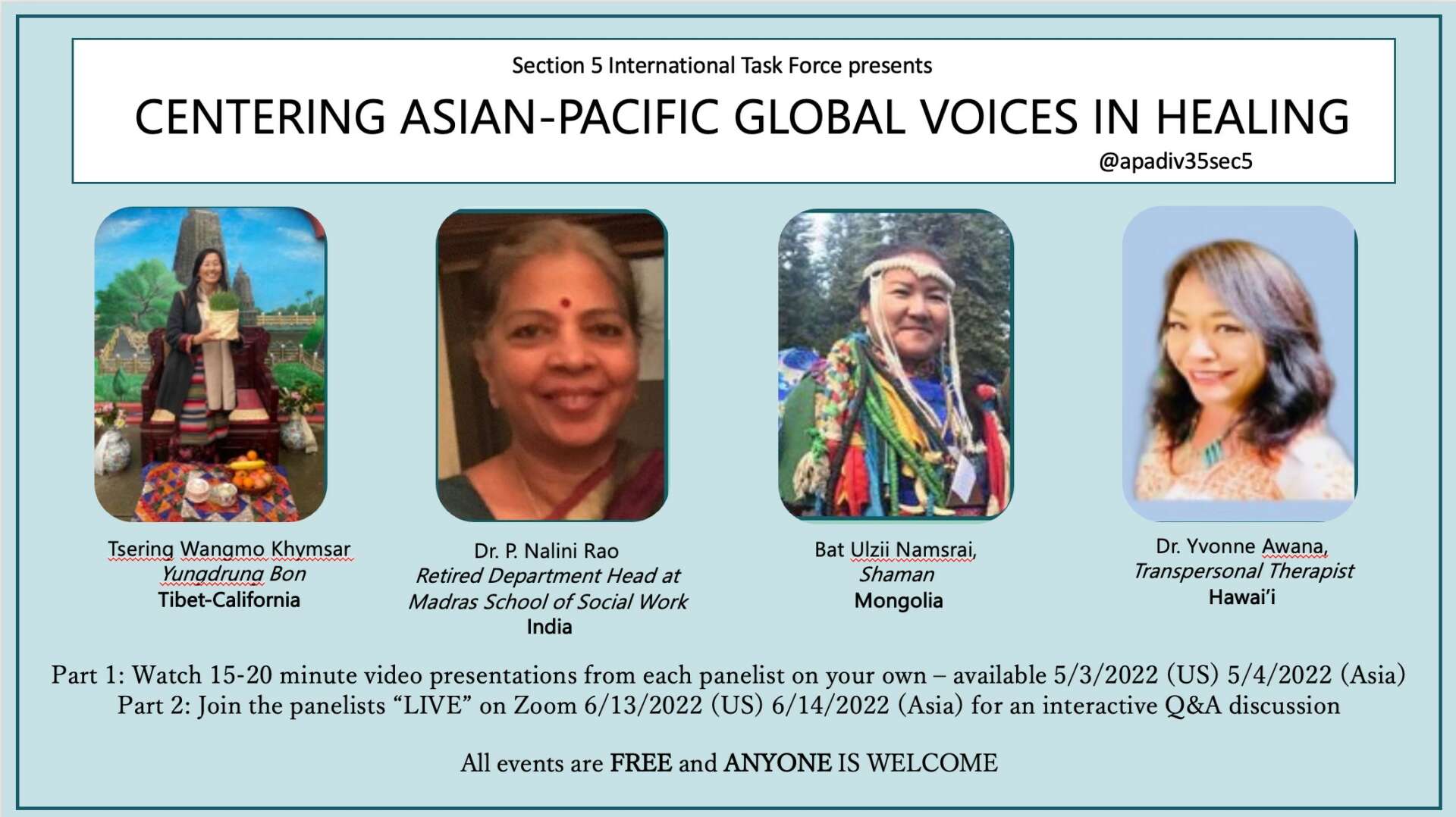

In an attempt to increase awareness around this, my co-chair and I, who served on the International Task Force for the American Psychology Association’s Division of Asian Pacific Women in Psychology (Division 35, Section 5), organized a virtual panel this past summer featuring female healers in de-centered parts of Asia. We hosted an online virtual event where the invited speakers included a shaman in Mongolia, a transpersonal therapist in Hawai’i, a practitioner of Yungdrung Bon from Tibet and India, and a leading researcher South India. Some practices they spoke about have been scientifically studied, while others have not and may never be. I was aware of my two minds while listening to them; one part of me was in awe of their expertise, the other was skeptical and wondering if it was all hubbub. My biases took a backseat when these women confidently shared about their craft. They did not look to others to legitimize their practices and were even conscious of being co-opted. Hearing their voices was a reminder to consider who sets the standard, especially when working with diverse communities. Evidenced based practices may not be the best option for all communities.

Contact Info:

- Website: www.drjennifertyoung.com

- Instagram: @therapyisheartwork

- Linkedin: www.linkedin.com/in/drjennifertyoung