Alright – so today we’ve got the honor of introducing you to David Shair. We think you’ll enjoy our conversation, we’ve shared it below.

Alright, David thanks for taking the time to share your stories and insights with us today. Let’s jump back to the first dollar you earned as a creative? What can you share with us about how it happened?

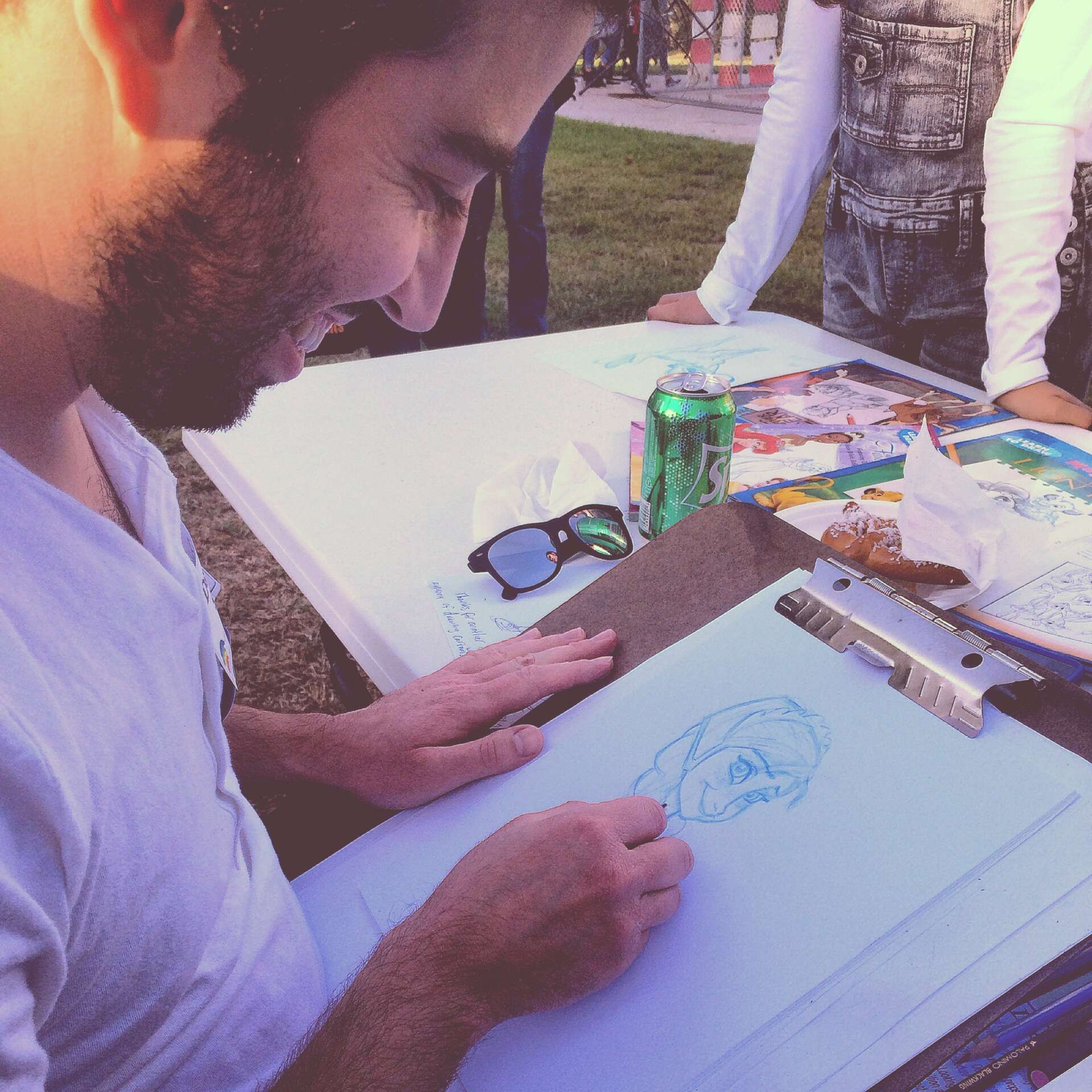

The first dollar I earned as a creative was when I became a caricature artist at Universal Studios upon first moving to Los Angeles. People would sit down in front of me, and it was my job to draw an exaggerated version of them using markers and color, right there and then. It was hard, it was low-paying, and I had to wear a starchy, collared shirt. But I was making money from doing art! The one problem was I wasn’t very good at it. The pictures would look like them, sure. But it wouldn’t be exaggerated. More like a family portrait. I lacked the “caricature” part of the caricatures. I’d also take forever to do one of them. I’d get caught up talking to whatever customer was in front of me and draw really slowly as a result. The customers were nice enough to talk even though they probably just wanted to get the picture done and go on “The Simpsons Ride”. My manager loved my customer service. The owner hated that I took so long. And I only had one drawing rejected that summer, which is actually a pretty good ratio of rejects to keeps. Maybe they liked what I did or perhaps they were just too polite to say otherwise about a drawing that took an hour to do and prevented them from riding “Revenge of the Mummy” a third time.

The second dollar I earned was for my first professional animation job. After the caricature summer, it took almost a year and a half of internships, drawing classes, improv, meeting people, learning to draw digitally, and creating a whole new portfolio to get my first paid gig at a studio. Mind you, I didn’t just get in. I had to pass an audition: the beginning to many an LA story. I was tasked with a storyboard test where a show would give you about 1 -2 pages of script to storyboard for free. Then they’d tell you if they liked it or not. I failed six of these tests hard, all over town. But each time, I made sure to ask what I could do better. Finally, on the 7th test, the first one where I got to storyboard and write, I got in. It was on a show at Disney Television Animation called “Fish Hooks” about fish who go to high school. There was a lot that happened on that show. But since reading this interview may be holding you up from going on Universal Studios “Shrek 4D”, I’ll only talk about my first morning there. I was hired to storyboard and write an 11-minute episode over six weeks. By myself. For Disney. For my first job. This made no sense. I had never worked at a studio before and suddenly I was in charge of an episode of a cartoon, one that costs thousands of dollars to make. This was…a lot. I arrived at Disney TV at 9 am for the story handout, where the story editor and leaders of the show go over the outline of the episode, rearrange it, come up with new ideas, new lines of dialogue, and put everything up on notecards on a big wall. These cards cover everything that happens that I’ll eventually have to board. Now this wasn’t just any group of leaders in that room. This was heavy-weight animation talent including C.H. Greenblatt, creator of “Chowder” and “Harvey Beaks”, Maxwell Atoms, creator of “The Grim Adventures of Billy and Mandy”, Bill Reiss, one of the funniest guys in animation, and Tim McKeon, who went on to show-run multiple shows. And once they began going over the story beat-by-beat, it was a whirlwind. They were coming up with new ideas. They were improvising beautiful jokes, left and right. They were playing comedy jazz right in front of me. And all I could do was sit and stare. I might occasionally nod. I didn’t know what was really happening. I was probably looking at some cool action figure someone had on a shelf and trying not to do anything weird. Then suddenly, every notecard was up on the wall, they turned to me, and said something to the effect of “David, does that work for you?” And I stumbled over something to the effect of “Yep.” What else was I gonna say? Nope?! I had never worked in animation before; I didn’t know what I was doing! Anyway, they gave me all those cards, and I took them back to my desk to try and storyboard a Disney cartoon. I was thrown into the deep end of the pool. And like those little “Fish Hooks” fishes, I had to learn to swim.

David, love having you share your insights with us. Before we ask you more questions, maybe you can take a moment to introduce yourself to our readers who might have missed our earlier conversations?

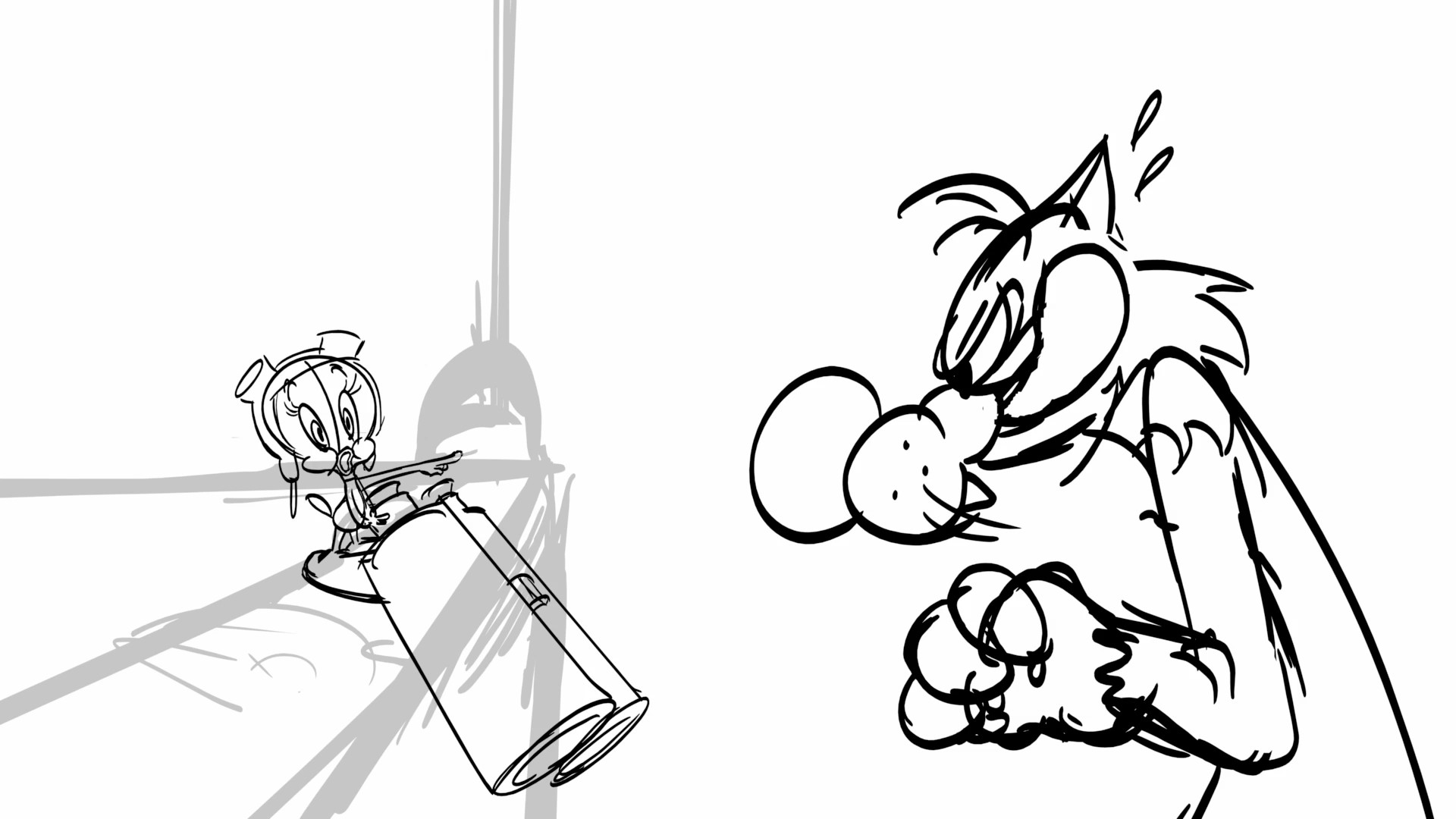

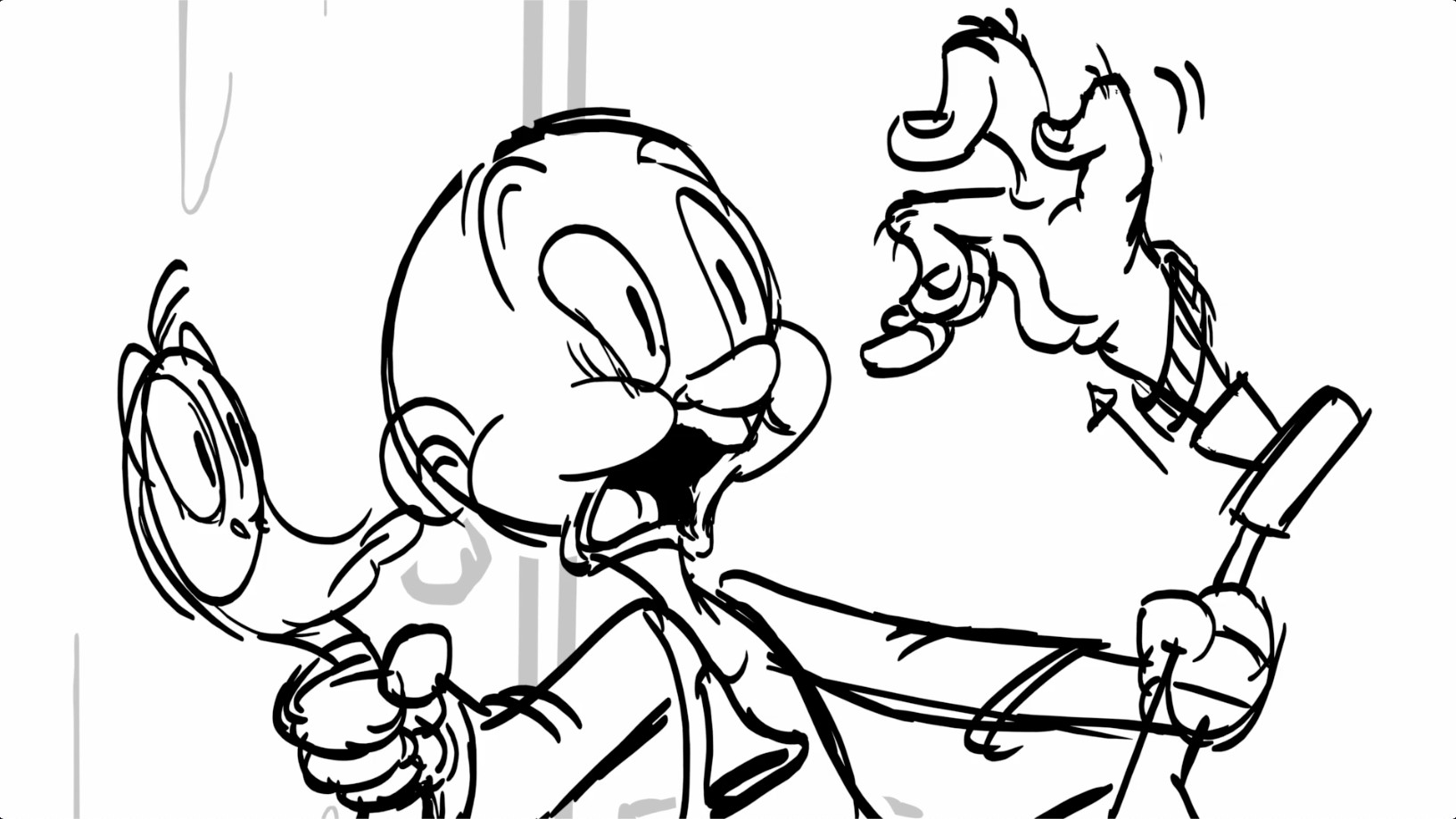

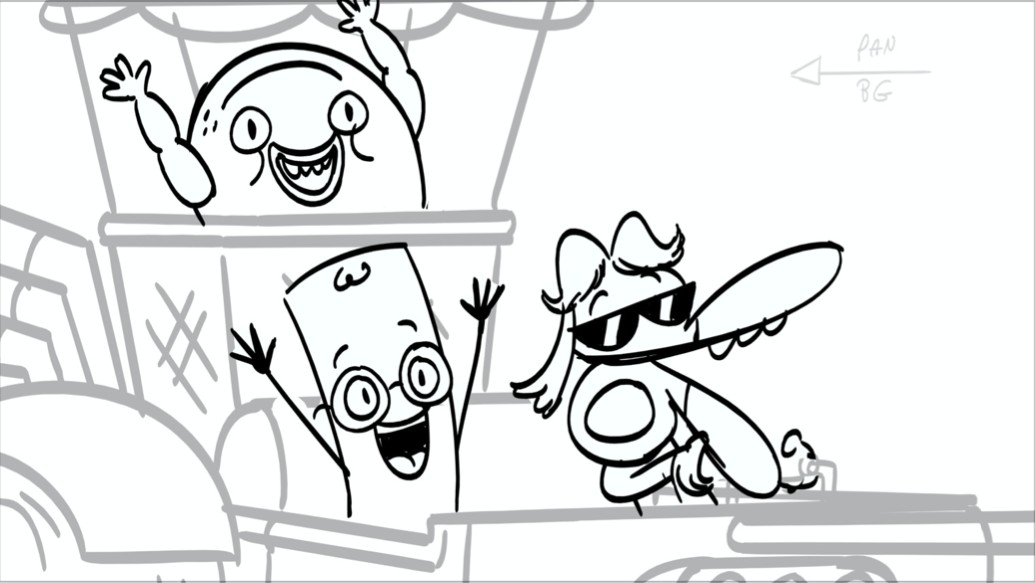

I storyboard and write comedy for animated television and film. That’s pretty much the gist of it. A storyboard is the first visual iteration of an animated cartoon – the sequential blueprint that, once approved, everyone on the production follows. It’s a big job and requires knowledge in a wide variety of areas such as acting, directing, cinematography, editing, and writing. In comedic storyboarding, a sense of humor is essential. If I’m boarding a scene from a script or an outline, I do my best to make it funny. Where can I add jokes? How can I make everything more entertaining? Oddly enough, I got into storyboarding for animation not from being a drawing wizard but from the world of improvisational acting. I honed my comedic sensibilities in improv and sketch writing classes at The PIT in New York City. And I eventually followed that with art school to learn the drawing part while continuing to do improv. By the way, as a board artist, you usually need to pitch the storyboards you create to the entire crew, clicking through the drawings while acting out the dialogue. So a performance background can really help. Not that many artists are onstage performers; the vast majority aren’t and can still be very funny. But it never hurts to have the skills; especially if you don’t want to get caught in an acting rut where you draw characters doing the same boring, old stuff – sticking out one hand, pointing, or putting their hands on their hips for example. There’s a zillion ways to pose out a scene and learning to act really helps inform that. Performance knowledge may also lead to other opportunities down the road such as animated voice-over work and script-writing, both of which I’ve been lucky enough to do. And when you’re trying to pitch your own show someday, you’re gonna have to entertain to sell it. That’s show biz!

Can you share a story from your journey that illustrates your resilience?

One instance where I bounced back was when I was trying to earn a promotion from storyboard revisionist to storyboard artist. A storyboard revisionist takes over after the storyboard artist is finished boarding an episode; they usually fix mistakes, adjust acting poses, clean up drawings, add in backgrounds, and take care of any directing notes. Storyboard revisionist is an important job, but they’re lower paid and don’t get their own episode to board. After that initial “Fish Hooks” storyboard assignment, I was staffed as a revisionist, working for nearly seven years in the role on various shows for Disney and Warner Brothers. I wanted to move up to storyboard but had missed out on being promoted a few times. The last time was the toughest because the storyboard job went to another revisionist that was younger and less experienced than me. It seemed like I had missed my chance and wouldn’t achieve a higher position. It felt bad, but instead of wallowing in it, I decided there must be something I was missing; I had to figure out what. After consulting with the directors of the show, I realized my drawings needed improvement. Every single drawing I made had to look good, something I wasn’t aware of because I was usually so focused on humor and acting that the draftsmanship didn’t seem like such a big deal to me. But it was! Every drawing was like a presentation of my skills. I began to make sure every drawing I made from then on had a clear line of action and solid construction and would not move on until I was satisfied. My drawings began to improve and guess what – my acting did too! The better you draw, the more confident you feel drawing characters in unfamiliar but more original acting poses. After months of working this way, when the next opening arose, I succeeded in making the jump to storyboard artist! And I still keep that drawing philosophy in my head to this day. Disclaimer: when I say make each drawing good, I don’t mean make them clean. It can be a rough drawing with construction lines. As long as it’s solid and clear, it should be fine. For safety’s sake, always check with your show on the level of clean-up you’ll need in your board drawings. End of disclaimer.

What do you find most rewarding about being a creative?

I’d have to say the most rewarding thing is the money! Just kidding. It’s decent but don’t expect to get rich as an animator – this ain’t the mid-90’s. Maybe it’s the fame? Nah. Unless you’re Matt Groening or Seth McFarlane, it’s rare to be that recognizable. What really is the most rewarding aspect of being an artist and writer is how much of YOURSELF you get to put into your work. Everyone’s life experience and point-of-view is unique to them, and it’s gonna show up in your art because you’re the one who’s making it. It’s what makes an artist and the pieces they produce unique. It can never be duplicated, only referenced. When you’re in control of storyboarding an episode (and especially when you’re writing the episode) it’s going to end up uniquely you. You may be drawing fish in high school like everyone else is drawing fish in high school, but the acting and story are being thought up by a guy who was the shortest kid in elementary school in suburban New York, who grew up reform Jewish, went to summer camp, performed theater, and watched “Looney Tunes” and “Married with Children”. That cartoon story is going to be way different than if it were boarded by a lanky kid who grew up in small town Iowa, went to church, played baseball, shucked corn, and watched “The Andy Griffith Show”. So depending on if it’s me or “Field of Dreams” Iowa guy, it’s going to be an entirely different cartoon with differing sensibilities. That’s why I always say it’s the crew that makes the show. A different set of people would make a different cartoon because it’s forged from their uniqueness combined, like a Captain Planet of Cumulative Trauma. In other words, learn to draw, learn to write. But most importantly, live life and keep being you – you’re one of a kind, and that’s your artistic calling card.

Contact Info:

- Website: www.davidshairart.com

- Instagram: @shairshare

- Linkedin: https://www.linkedin.com/in/david-shair-78351b11/

- Twitter: @shairshare

Image Credits

©Warner Brothers Animation (on the two “Looney Tunes Cartoons” storyboard panels) ©Nickelodeon Animation (On the “SpongeBob Squarepants” storyboard panel and the “Rock, Paper, Scissors” storyboard panel)