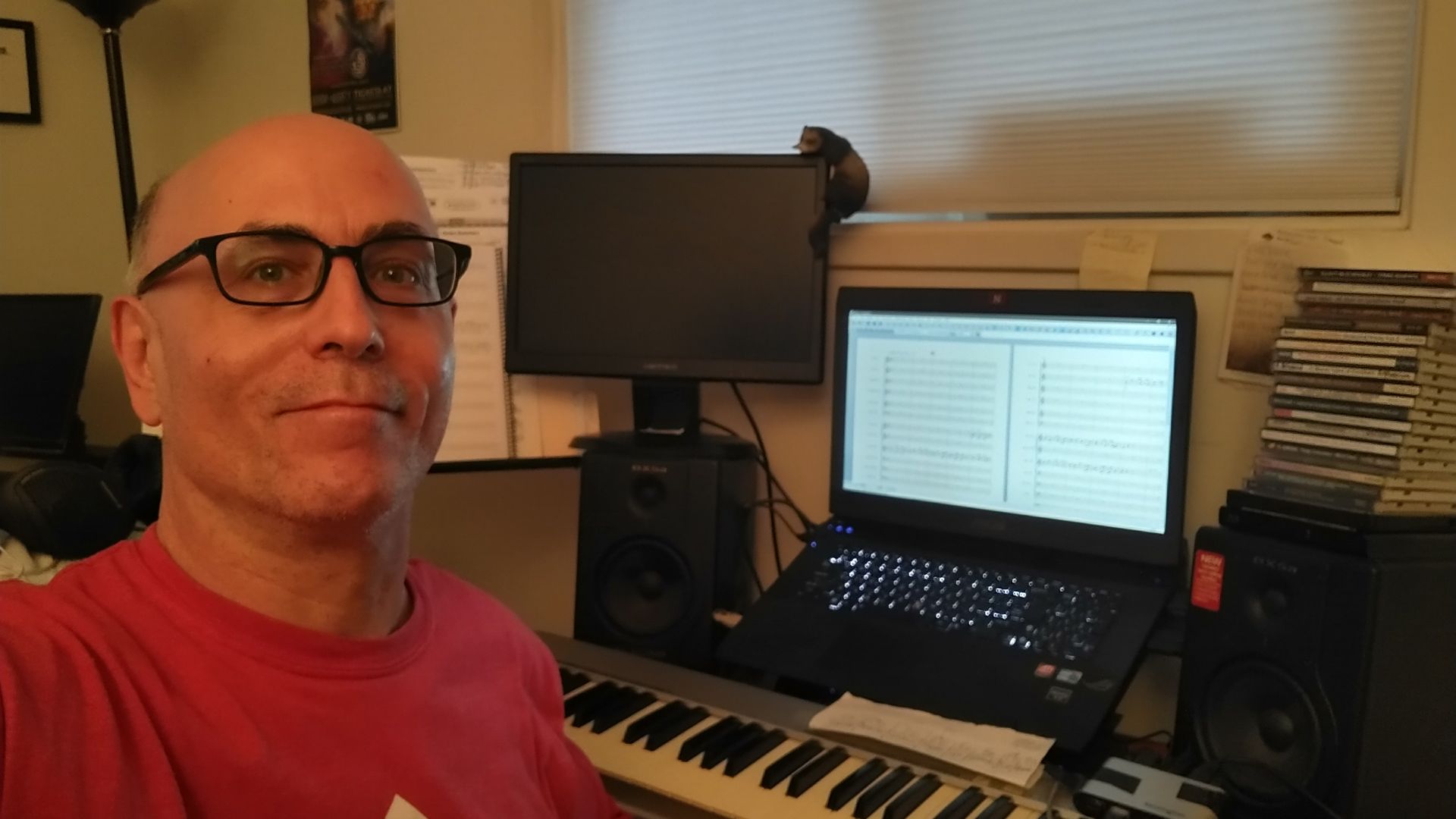

We were lucky to catch up with David Gaines recently and have shared our conversation below.

David, thanks for joining us, excited to have you contributing your stories and insights. Do you think your parents have had a meaningful impact on you and your journey?

My parents were very pragmatic people and my father in particular didn’t really relate to idealism. But they were both fans of classical music and pretty literate in the standard repertoire, and as a Jewish family we were all aware of classical music icons like Leonard Bernstein, Yascha Heifetz, Vladimir Horowitz, etc. This made wanting to pursue a career in or adjacent to classical music acceptable, for lack of a better word! I vividly remember my mother waiting outside in the car every Sunday morning doing crossword puzzles while I had my weekly euphonium or bass trombone lesson. I also remember how calm and encouraging my dad was when he drove me into New York City for my audition for Northwestern University’s School of Music, which was probably the most nerve-wracking car ride of my life. When I previously let them know – after it became clear across my high school years that I was good enough – that I wanted to pursue a music degree, these two very pragmatic people stood aside and let me pursue my dream. Many years later I knew how proud they were when they got to attend the world premiere of my second symphony.

David, before we move on to more of these sorts of questions, can you take some time to bring our readers up to speed on you and what you do?

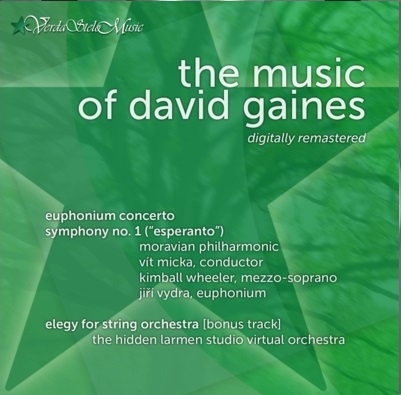

I am a classically trained composer with university and conservatory training up through the doctoral level. I focus on what we refer to as concert music, which includes music for large ensembles such as orchestra and symphonic band as well as chamber music, which would include duets, trios, and quartets. Since I became a musician in the mid-1970s I’ve also been quite involved with electronic and computer music and studied those subjects extensively in college and graduate school.

Before switching to composition in college, I began my journey through the music world as a euphonium and bass trombone player in junior high and high school, focusing on playing in concert bands, wind ensembles, a youth orchestra, and brass instrument groups. I was the principal euphonium player of the Connecticut All-State Band in my junior and senior years of high school, and was selected to play in the euphonium section of the Music Educators National Conference All-Eastern United States Band in my senior year. Those experiences were critical in convincing me that I had the talent to pursue a career in the music field, whether as a performer, an educator, an arts administrator, or a combination of all three.

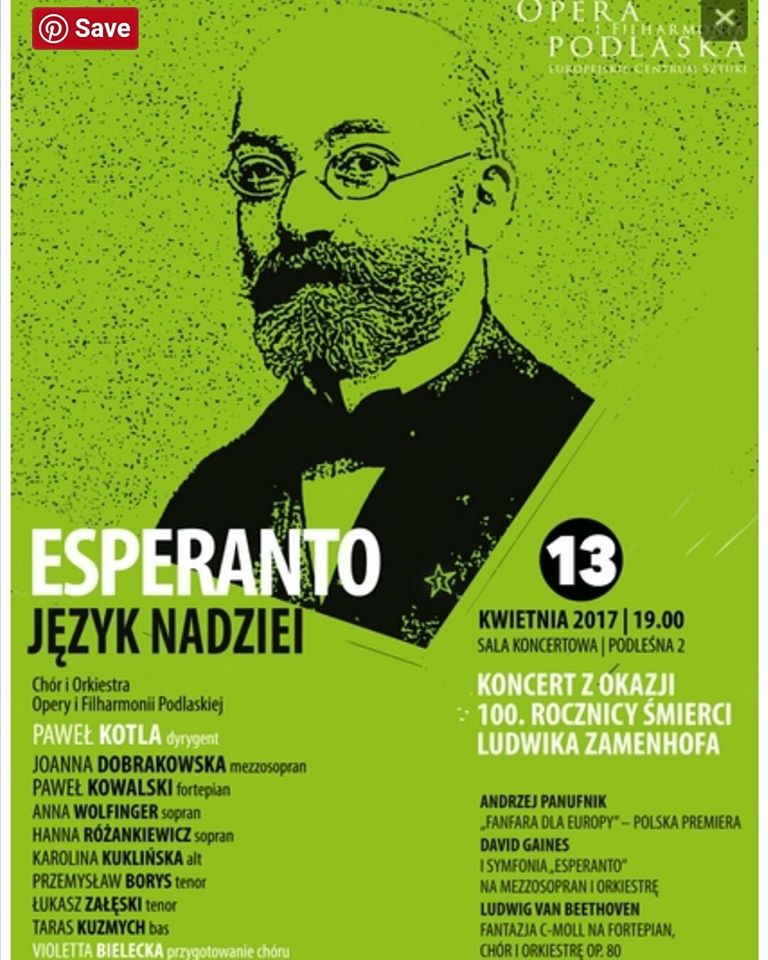

As a composer, I’m most proud of seeing people over the years perform my music widely, and audiences appreciate it. I differ from my colleagues in my focus on unusual or underutilized combinations of instruments and unusual orchestration techniques, as well as my use of the international language Esperanto for texts for my vocal music. Esperanto is a rich and severely underutilized resource for composers willing to explore ignored or hidden sources of textual material, specifically poems and essays.

Do you think there is something that non-creatives might struggle to understand about your journey as a creative? Maybe you can shed some light?

Over the years I’ve encountered a number of people who are puzzled as to why anyone would pursue a career in music, let alone classical music, when it’s almost certain to be a financial struggle and the odds of success (usually defined by such people very differently than we would) are so low.

One answer is that, for me, this is a part of what I do in life, as I wear several different hats and find that to be very suitable for my personality. I’ve had a very wide array of interests, some far beyond music, since childhood and will continue to operate that way the rest of my life as far as I can tell. I was also always prepared for struggle and acquired a variety of skills over the years, since high school, unrelated to music that made me employable. I think we’ve all had a variety of day jobs in this field – composer Philip Glass not only had a New York City tax driver license, he held onto it even after his first opera was a success! In his autobiography he tells the story of a woman he was driving in his taxi who noticed his license on the dashboard and said “Oh that’s funny, I just saw an opera by a composer named Philip Glass.”

Another answer is, as I read somewhere long ago, we do this because we can’t not do it. It’s really as simple as that.

What can society do to ensure an environment that’s helpful to artists and creatives?

(1) Increase funding, both public and private, substantially, by orders of magnitude, and (2) put music education back in the place of respect that it held in public school systems across the country when I was a child. The transferable skills acquired through music study and music performance are many and it’s incredibly sad how many people don’t understand that.

I remember even in elementary school it was taken for granted that you would learn the rudiments of how to read music notation, how to play an instrument (usually the piano), who the great composers and songwriters were, etc. All of this teaches social skills and trains the brain in ways that stay with you for life. Music education has always represented a fantastic return on investment.

Contact Info:

- Website: davidgainesmusic.com

- Instagram: davidrgaines

- Facebook: davidgainescomposer

- Linkedin: davidgainesmusic

- Twitter: davidrgaines

- Youtube: davidrgaines

- Soundcloud: davidgaines

Image Credits

Photo of DG holding an oval baritone horn: Barry Bocaner

All other photos: either unknown or selfies taken by DG