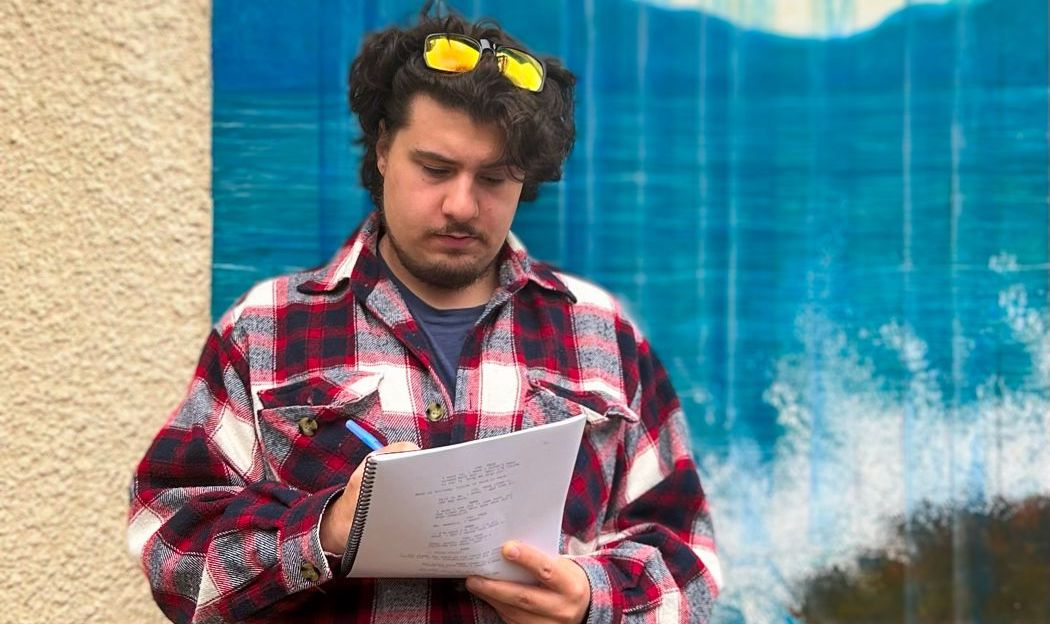

Alright – so today we’ve got the honor of introducing you to David Barbeschi. We think you’ll enjoy our conversation, we’ve shared it below.

David, thanks for joining us, excited to have you contributing your stories and insights. We’d love to hear about one of the craziest things you’ve experienced in your journey so far.

A lot of crazy stories come to mind. As a freelance screenwriter, I strive to be open to my clients’ suggestions. After all, most of the scripts I’m commissioned to write are personal to them. That said, sometimes you get ridiculous notes. Just last month I had a client who – with a straight face – asked that I insert a twist at the end of our “Rocky”-style story that revealed “the whole movie was just the main character’s dream”.

But by far the craziest story was my very first screenwriting gig, where I had to trim down and rewrite a science fiction script.

As advertised, the task was straightforward: a science fiction novelist had turned his book into a screenplay and the producer who optioned it wanted someone to trim it down from 126 pages to a more digestible 90-110. Sounded simple enough.

After I signed the agreement, I found out the script was actually nearing 300 pages in length… and that every other paragraph in the script was written in an alien language alphabet the original author invented composed of forward dashes and hyphens!

As insane as this was, the author felt this was completely acceptable and that the producer and I needn’t worry about whether potential executives or actors wouldn’t be able to comprehend half the script: after all, he added a “Rosetta stone” section on Page 1, explaining what letter every symbol corresponded to. He unironically told us that Brad Pitt would have a field day deciphering the screenplay, my services weren’t really required.

The plot itself was also very bizarre. Every character spoke with the eloquence of a university professor, including an eight-year-old boy who – for three whole pages – delivered a very off-putting speech about the dangers sexual intercourse.

Needless to say, I felt tricked, this was a much harder job than advertised… but more importantly, I always try to get the job done right. And I knew that even if I merely trimmed away the “alien” paragraphs and reduced the length of the various tirades, the script would still be unsellable because the real issue lied in the script’s story. What was needed wasn’t just a trim, this script need a whole rewrite, from the ground up. I explained all this to the producer, who was very understanding and decided to revise our contract.

David, before we move on to more of these sorts of questions, can you take some time to bring our readers up to speed on you and what you do?

I have been a storyteller as far as I can remember, I’ve always had fun creating stories and sharing them with others. Fast-forward a couple of decades and here I am, doing the same thing for a living.

As a screenwriter, I primarily operate during what is known as the “development” phase of film production. Clients hire me to write screenplays based on their ideas, or to analyze, diagnose and fix their own scripts, or to create pitching material, writing copy and designing decks and series bibles that will appeal to studio executives and production companies.

The job trickles down to three steps that you go through in a loop:

1. absorbing stories,

2. telling stories

3. fixing stories.

The “absorbing” step is the easy one. It ranges from going to the theater and watching a movie — I mean, “doing research” — to just shutting the hell up and listening. Listening to the bits and scraps of conversation you catch in the bus, but also – and more importantly – listening to the client. Who are they, what are they trying to say, what’s the message they’re trying to get out there? They feel theirs is a story worth telling, it’s my job to understand why and how others can feel that too… and so I need to listen.

Once I’ve done that, I move on to the next step: writing the story. I take what I’ve absorbed and structure it into an emotional journey that will impact a reader and, later, an audience.

The keyword, there, is “structure”. Some of my clients’ ideas will be based on their real life experiences, be it the pain of a breakup, the trauma of war, etc… but real life doesn’t have structure. Even documentary filmmakers try to craft a narrative around what they shoot. As such, like with any adaptation, the original idea will need to be tweaked and distilled in order to become more poignant, which is why it’s essential that I establish a collaborative relationship with the customer: they’ll help me help them.

Finally: fix that story. There’s just no way the first draft will be flawless. So I crank out another draft, and another, until I’ve managed to craft a screenplay that tells the story my customer is trying to convey in a way that will seamlessly translate to a visual medium.

And then I repeat the process with the next job.

Sometimes, I’m hired to only do that last step for an already-written screenplay. In those situations, I pride myself in my ability to identify the issues within a script and giving a diagnosis that respects the author’s original intent. It’s easy to say “none of this works, scrap it all and start from scratch”… what I specialize in is identifying what the writer is trying to say and helping them tell that story better.

Is there something you think non-creatives will struggle to understand about your journey as a creative?

It’s interesting you ask that, because I was recently in a debate with people from all walks of life. Some of us were creatives, some weren’t. The subject of generative AI came up (the WGA strike was still ongoing) and the room was split. Most were against it, some were for it. My stance landed somewhere in the middle:

Due to its very nature, there’s no doubt that tools like ChatGPT can replicate the emotional impact of a human writer, given enough time and training (hence why it’s essential to regulate it now, while we still can). My issue is that… people are flocking to using these tools now, when they’re still in their infancy. As terrible as ChatGPT is at producing a screenplay scene (and it is, trust me, I’ve tried)… some consider the results it yields to be acceptable.

And that’s a problem, because if you watch recent blockbuster films the storytelling quality has already begun to dip, the characterizations will be flimsy, the stakes will be superficial, and yet some viewers will still argue that it’s good. Couple that, now, with AI-generated scripts, and the standard for “what makes a good story” will be irrevocably lowered.

The example I gave was that of a chef. The job itself can be dumbed down to “making food for a client” but in reality, it’s not as simple as that. There are myriad factors to be considered, small practices and tricks you implement to not just make a meal, but make it a good one. It needs to be seasoned a certain way and you need to apply that seasoning in a certain way, etc. It’s a meticulous job.

The response I got from a non-creative was “who cares about how it’s been seasoned, the point is that the customer gets his food.” And that’s the difference.

The non-creative thinks it’s all about reaching the destination, the creative knows that doing so without going through the journey is a futile endeavor.

What’s been the best source of new clients for you?

Word to mouth, by far.

I treat every tasked assigned to me with a sense of urgency and I get the job done. People are happy about it and since I began specializing in screenwriting, half of the income I generate is from returning clients.

That said, and I keep saying this to up-and-coming writers: networking. That’s what it’s all about. Get out there, meet people, attend festivals and grab a drink with a director whose work you enjoyed. Don’t be afraid to write the occasional pro bono 5-page short for someone, because that will 1) result in produced work, which is always good to have and 2) will result in a paid feature film gig, in the future.

Contact Info:

- Instagram: davidbbski

Image Credits

Yves Arispe, @gentlemanyves