We were lucky to catch up with Danyon Davis recently and have shared our conversation below.

Alright, Danyon thanks for taking the time to share your stories and insights with us today. How did you learn to do what you do? Knowing what you know now, what could you have done to speed up your learning process? What skills do you think were most essential? What obstacles stood in the way of learning more?

My entry into the arts was through a summer program for high school students in New Jersey called the Summer Arts Institute (SAI), which I was accepted into the summer following my 7th grade year. I auditioned for the theater department, but at 12 years old the coordinators of the theater department thought I was too young to take on as a student. The specific area of study at SAI that I was accepted into was a newly conceived department called Interarts, which was one department among seven others offering pre-professional, conservatory-based study in the areas of theater, dance (ballet & modern), singing, classical music, jazz, creative writing, and visual arts. The course of study we followed in Interarts was based on interdisciplinary art and communal art making. One co-coordinator of the program, Darrell Wilson, was a ballet dancer/ glass blower/ and sculptor; he was also a professor who taught experimental filmmaking at NYU and figure-drawing at Rutger’s Mason Gross School of the Arts. The other co-co-coordinator, Maureen Heffernan, was a former musical theater performer turned freelance director and one-time artistic director of the George Street Playhouse, an esteemed regional theater in New Brunswick, NJ. In addition to our work with Darrell and Maureen, we had workshops with the faculty of the other areas and worked toward creating a culminating “Happening” inspired by the performance art collaborations in the experimental art world of the 1950s, ’60s, ’70s, and ’80s.

One of the guiding propositions of the Interarts department was to explore how teens in the late 1980s might relate to the concept of the “Renaissance Man”. I learned a tremendous amount being exposed to a multitude of art forms– and eventually found that I lacked the aptitudes required to apply myself technically in music, dance, and fine art. However, being exposed to the details of several techniques of expert craftspeople taught me an appreciation of craft. I would return to SAI in subsequent summers to study acting discreetly in the theater department– and I approached the study of acting with the understanding that I did have the aptitude to hone my abilities to a high level of craftsmanship in that field. One lasting impact of my Interarts baptism was my abiding identity as experimental artist. My artistic role models at age 12 became John Coltrane; Kieth Haring; Allen Ginsberg; the comic book illustrator, Bill Sienkiewicz; Spike Lee; Salvador Dali; and James Dean.

My interest in acquiring acting technique eventually led me to the North Carolina School of the Arts (NCSA) for my senior year of high school. That was followed by my acceptance to the Juilliard School for my undergraduate years. I became a member of Group 25, the Juilliard Drama Division’s 25th cohort admitted since its inception in 1968. Juilliard was the ideal scenario to hone my craft, by virtue of the fact that we worked on two projects a semester. It was a very practical education in which we were tasked with not only synthesizing an approach that best suited us individually, but we also were constantly challenged to apply that approach in a new style every seven weeks for four years.

When I was finishing high school at NCSA, it had become my habit to spend a lot of time in the library. I read a number of trade journals like the Johns Hopkins Theatre Journal and Yale’s Theater Magazine, along with The Drama Review. Living in New York City during my college years afforded me the opportunity to see the work of artists like the Wooster Group, the SITI Company, Robert Wilson, and Bill Irwin up close. I used every opportunity I had to create new work melding the classical techniques I was learning at Juilliard with the experimental techniques inherent to the work that held my interest downtown. Eventually, my teachers did implore me to focus more explicitly on the more traditional approaches that were the backbone of the Juilliard training. And after making that commitment, I came to appreciate that the training I was receiving at Juilliard put information in my body that I could access fluidly in any classical, contemporary, or experimental setting.

I don’t know that I would wish to have sped up my learning process in any significant way. Acting is an interesting art form. Some actors draw on experience more in their work, and some draw more from their imagination. I was thrust into a graduate-level learning environment at age 17- – most of my 19 other classmates already had a four-year degrees. I had no other choice than to work from my imagination. But I do think that approach agrees with the kind of experimental artist that I am most intrinsically.

When I look back on what is most important in making the transition from precocious adolescent to becoming a professional artist, I think one of the most important factors is the opportunity to develop a sense of belonging. Without a sense of belonging, it is difficult to develop the confidence that is required to access vulnerability and to take certain risks that are necessary for success, or to develop the emotional regulation that is necessary in cultivating resilience.

In addition to experimental work, I was also drawn early on to the traditional resident/ repertory company model of theater making that was being phased out for economic reasons as I was entering the world of professional theater. I think that seed of interest for me was the cohort of 12 young artists that I found myself among all the way back in my first year in Interarts at SAI at age 12. I think one of the biggest obstacles to learning and reinforcing essential skills in my field is the erosion of those resident/ repertory company structures that facilitate a journeyman approach. Overall, the early career instability– the lack of structures that can hold a young theater artist– is a big problem. Young artists need stable structures to nurture them, while also providing a safety net that allows them to ground themselves artistically, emotionally, financially, and spiritually.

Great, appreciate you sharing that with us. Before we ask you to share more of your insights, can you take a moment to introduce yourself and how you got to where you are today to our readers.

I often refer to this quote by the early 20th C. French theater director, producer, actor, and dramatist. Jacques Copeau when people ask what I do- –

“The essence of theater is action; and the essence of action is movement.”

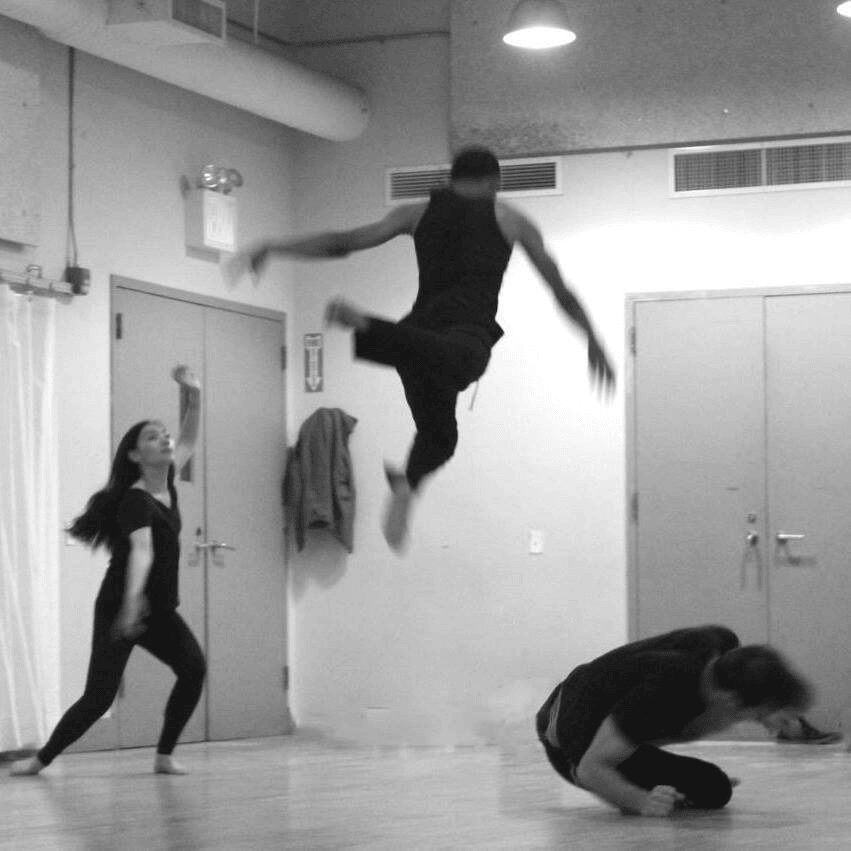

As an acting professor specializing in movement, I teach actors how to gain command of their bodies so that they can access their instinct, emotions, and imagination to express themselves fully and freely. This involves physical conditioning to improve objective physical attributes such as physical strength, flexibility, precision, and coordination. This also involves helping actors to “get out of their heads”. In our work together, my aim is to give actors another source to work from in their body. That other source is their gut, their core, their belly- – what we refer to in the work as the actor’s “center”.

There is a rudimentary brain within the center known scientifically as the “enteric brain”. The fascia and nerve endings that line the gut are very similar to those that compose the more developed brain in the skull. When you go to the bathroom at the same time every day, it is the enteric brain functioning; when you get sick to your stomach with anxiety, it is the enteric brain functioning; when your crush walks in the room and you get excited with butterflies in your tummy, it is the enteric brain functioning. An actor must train the ability to work from the enteric brain in order for their work to be the most compelling and the most authentic that it can be.

Several of the actor’s most important tools live in the center. Among those tools are the connection to the breath; the ability to draw on inner focus and inner strength; sense of rhythm; and the wellspring of impulse. Per Copeau’s quote, the essential language that the actor uses for expression is action. An actor creates a role by authoring a physical score, or a sequence of actions that conveys their character’s experience of relationships with other characters and their experience of the events of the play. Ideally, this physical score resonates with the fullness of the actor’s artistry, and each action within the score is relevant to the meaning embedded in the script. It is also paramount that each action the actor chooses is repeatable and sustainable over eight shows per week (or 28 takes in a row on a movie set at 3am in the morning). Whatever the choice in action may be, it begins as a signal of impulse from the center, from the gut. Acting is much more about the sequential visceral flow of these impulses into physical actions than it is about psychology and getting the character’s thoughts in order. If you commit to the character’s actions, the appropriate thoughts and feelings will follow naturally.

I graduated from Juilliard in 1996 with a degree in acting. I was invited to return to Juilliard in 2009 to apprentice the last remaining founding faculty member still teaching full-time at the school, Moni Yakim. Moni taught every actor who came through Juilliard over a 50+ year period. Actors such as Kevin Kline, Laura Linney, Viola Davis, Adam Driver, and Oscar Isaac attest that they owe a great deal of their extraordinary ability to make dynamic choices in action to their study of Moni’s Movement/ Physical acting methodology.

I shadowed Moni, learning his techniques, in virtually every one of his classes for five years. I taught alongside him, and covered his classes when he was working out of town or, occasionally, when he was ill. Eventually, he deployed me to conservatories around New York City such as Circle in the Square Theatre School, the Neighborhood Playhouse, HB Studio, and Stella Adler School of Acting to continue developing as a teacher on my own. Moni had never chosen to export his methodology like many other well known actor training learning practices such as Lucid Body, Bartenieff, or Linklater Voice. Moni always expressly stated that my task was not to teach his methodology, but to adapt it.

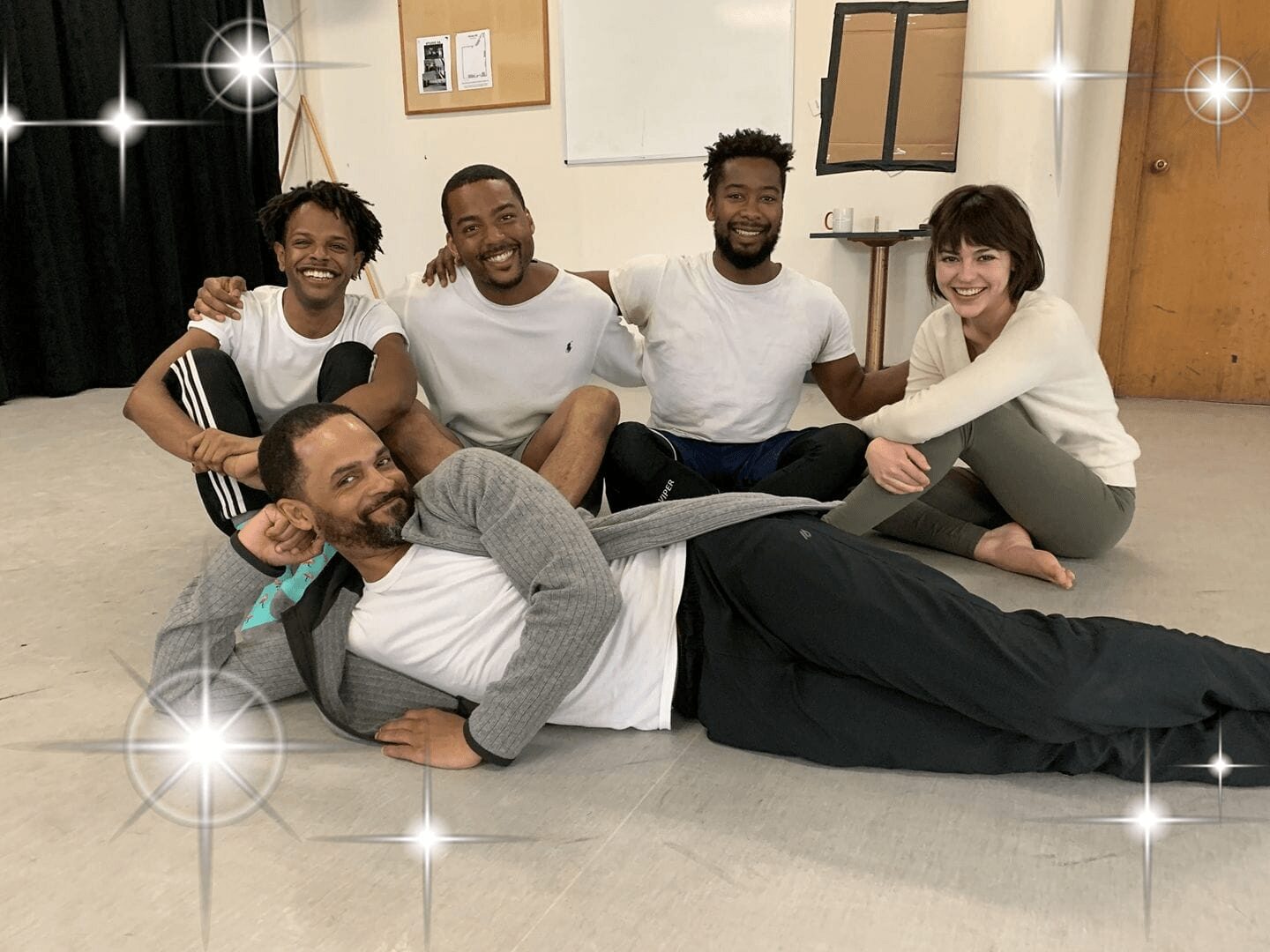

I would go on to become the Head of Movement at Stella Adler, and subsequently the Head of Movement at American Conservatory Theater (A.C.T.) in San Francisco, where I was also the Director of the MFA Program before the board of trustees decided to discontinue that historic program in a realignment of A.C.T.’s long-term strategic plan. I am presently a full-time faculty member at Syracuse University (SU). I am thrilled to be working at SU. It is an exciting opportunity to collaborate with a vibrant, progressive young faculty who are custodians of traditional approaches to actor training as well as innovators breaking new ground in training a new generation of theater artists. SU is a Research 1 university and it is therefore extremely meaningful to be able to work with colleagues in various disciplines across the campus in facilitating ways in which our scholars can best impact the world and play an active hand in shaping the future.

The SU Department of Drama also enjoys a formal partnership with Syracuse Stage, a regional theater renowned for excellence over its 50-year history. This partnership affords me opportunities to collaborate with my students and my colleagues in production, as well as the classroom; it also provides an excellent venue for me to continue developing as an actor and as a movement coordinator in the shows to which I contribute. As a movement coordinator in productions, I serve a role as a resource to help the actors, the director, and the design team to meet the physical needs of the play. Some of my most cherished work in my career has been my work as a movement coach or a movement coordinator. That work does not provide a platform for the expression of vision like a director, nor does it provide the rush of connecting with an audience that one experiences as a performer- – however, it is an opportunity to be a problem-solver and to open up possibilities for others. My work as a movement coordinator ranges from helping actors to exhibit a history of expertise with a prop or a skill, to helping a set designer adapt a feature of the set so that it can be used efficiently and sustainably by the actors. Overall in my work in the classroom and in production, I find myself most satisfied by those moments when I help others to discover new choices and opportunities, and when I help actors to transcend the limits of what they previously thought was possible.

In addition to my work with Moni, I have also served as assistant director on the world premier of one of Arthur Miller’s last plays (RESURRECTION BLUES), as well as associate director to Bill T. Jones on the musical adaptation of the movie SUPER FLY. Additionally, I was fortunate to enjoy a long relationship with Thomas Richards and Mario Biagini, the artistic leaders of the recently shuttered Workcenter of Jerzy Grotowski and Thomas Richards, and the teams of artists hailing from around the world that conducted outstanding research there since its inception in 1986. In all of these instances, I have benefited from close working relationships with true master artists. I do my best to weave all of those experiences together in my ongoing work, to build learning experiences that will help young artists to be more and most authentically themselves and to grow in extraordinary ways.

Is there mission driving your creative journey?

For a long time, my chief definite aim was to “change the way that actors are trained in America”. I had hoped to do this mainly through continuing in leadership roles at legacy graduate-level conservatories. That lofty goal was altered significantly by my experiences in the Covid-19 pandemic. For one thing, I had the opportunity to run an historic training program for two years, ultimately dismantling it and guiding the teach-out process to the demise of the A.C.T. MFA Program in June, 2022. I came to understand how vulnerable our artistic and educational institutions are, and how difficult it is to focus on innovating when an entire sector is besieged and focused merely on its survival.

I appreciated the opportunity to run the school and I was honored by the faith that was placed in me to sustain the school’s integrity. However, splitting the focus between administration, teaching, and art making was not something I felt was sustainable in my own life moving forward. Most of all, I missed teaching and the focus on changing the individual lives of my students training in small cohorts, whose artistry I got to know through frequency of contact in the classroom. So I gave up my aspirations to implement wide-scale changes through continued vertical advancement in legacy graduate-level conservatories as administrator.

My former school (A.C.T.) was an MFA program; the school where I am now (SU), is a BFA program. I find the work with undergraduate students, particularly my work with the first and second year students, to be uniquely rewarding. The SU Department of Drama is a “conservatory-based” program. The focus is therefore not entirely on professional training, but also on navigating the transition into adulthood, developing autonomy, and shaping young people into being empathetic, engaged citizens.

When I was teaching in NYU’s similarly “conservatory-based” undergraduate studio program, the then Chair of Undergraduate Drama, Rubén Polendo, emphasized that our main mission in the first two years was to help forge a relationship between the student and the field. It could be that our undergraduate acting students might find themselves utilizing the foundation they received in training as actors as a bridge to careers in theater management, playwrighting, directing, or design. We started them on a course of study that was focused on acting technique, and they then brought that experience of “learning how to learn” with them into their pursuits of further interests.

I find myself increasingly driven to work in the way that Rubén set out for us as a faculty, especially as I experience more and more of the ways that young people in their high school years were impacted by the Covid-19 pandemic. So much of the transition from junior high school to high school is about learning to embody core values in unmediated, synchronous settings. Young people deeply need spaces where they can develop and practice pro-social skills that are the basis for developing healthy adult relationships in the future. High school theater rehearsals, classes, competitions, and performances are foundational experiences of community that help to form essential understanding of meaningful togetherness and shared purpose. A lot of that was disrupted by the pandemic. It is also well known that the isolation everyone experienced through the pandemic fed into a rise in anxiety and depression across all demographics– and in teens, in particular. Moreover, teen depression and anxiety has been on the rise for the last fifteen years with the inexorable impact of social media on young people’s lives and the decline of free play. So rather than the grandiose aim of running schools and guiding the changes that will lead to the way actors are trained across the field, these days I try to focus primarily on sharpening the tools young actors need to resist distraction and improve their abilities to connect with themselves, each other, and the work in my classroom.

Can you tell us about a time you’ve had to pivot?

One of the byproducts of my time directing an actor training program during the pandemic was a growing awareness of the relationship between young theater artists and the exponential advancement of digital content production. In a June 5, 2020 article in “The Financial Times” entitled “Sam Mendes: how we can save our theatres”, the esteemed British film and stage director, producer, and screenwriter Sam Mendes attempted to draw attention to the multi-modal performance/ storytelling ecosystem, which includes theater training programs and professional theater production, as well as film and television production and the rapidly growing streaming services. Writers, directors, actors, designers, and artisans who work in recorded media all cut their teeth by learning to ply their respective trades on the proving grounds of theater training programs and live professional theater. Mendes wanted the world to know that training programs and live theater production, which were hit so hard during the pandemic, actually made the windfall profits that streaming services enjoyed during the pandemic possible. His argument was that the recorded media components of the ecosystem would not be able to withstand the decimation of the training programs and live theater without collapsing themselves. He felt it was therefore imperativet for recorded media producers and their influential partners such as governments to play an active hand helping training programs and live theater to restore their health and thrive once more.

I have long recognized that the generation of theater artists I graduated with in the mid-90s is the last generation that could ever aspire to make a living by practicing solely as theater professionals. The young artists I train today will need to work in film, television, and emerging new media platforms in order to sustain themselves as professionals. They also need to acquire digital literacy in order to promote themselves, engage in the audition process, and to deepen their ability to make an impact as artists in the 21st Century. This does necessitate “changing the way that actors are trained in America” because traditional voice, movement, and acting/ scene study classes along with stage productions that have traditionally been the backbone of conservatory training are not enough in the 21st Century. There are also fewer experiences of a wide spectrum of live theater that will inform their aspirations.

In the depths of the pandemic, we needed to start programming classes that taught students how to self-tape (their auditions), frame camera shots, and execute production design as we did not know when or even if we would ever return to live in-person performance. We also taught students to build personal websites and how to program those websites with content that they wrote, shot, and edited themselves. This required teaching them skills in storyboarding, sound engineering, lighting, digital editing, social media, and animation. And as we continue moving through the other end of the pandemic, we also must acknowledge that our approach to training actors will need to adapt to the opportunities and competition that A.I. represents.

The future of actor training lies far beyond the skills needed to navigate a rehearsal room and to be proficient on stage in a live theater setting. I am very excited to continue adapting my pedagogy to account for these needed changes in the small ways that I can. I am also very energized by my conversations with my colleagues who have greater insights than I have as to how to seize on new opportunities, transmit innovative new skills, and bring about the long-term evolution of how we train young people to navigate and succeed among the emerging realities of the field.

Contact Info:

- Instagram: danyon_davis

- Linkedin: Danyon Davis

- Youtube: @danyondavis

Image Credits

Denise Winters

Thomas Brunot

Leslie Silva

Beryl Baker

Emma van Lare