We were lucky to catch up with Dana-Marie Bullock recently and have shared our conversation below.

Dana-Marie, appreciate you joining us today. Can you talk to us about a project that’s meant a lot to you?

I am currently developing a performance, The Unspeaking Woman, that extends the body of work I am producing for my upcoming MFA thesis show at Pratt Institute. Drawing upon my research and the material experiments I produced in the form of paintings, sculptures, photographs, and installations, The Unspeaking Woman marks my debut with live performance and explores themes related to disability, trauma and loss, bodily autonomy, sexuality, and gender.

Collectively, this suite of work attempts to describe my experience with Spasmodic Dysphonia, a rare neurological voice disorder that affects my ability to speak. The three-part, 25-minute performance features a number of unstretched paintings and sculptures I have developed related to spasmodic dysphonia and the history of genetic disorders latent in my maternal family line, and my childhood growing up in Jamaica.

Asking viewers to examine their own relationship to speech, especially in cases where speech comes comfortably or easily, The Unspeaking Woman embodies aspects of my life that my visual art practice focused on materializing. Combining these two approaches, the interdisciplinary performance showcases an approach to artistic production that stretches between the studio and stage and which emphasizes the adaptive nature of a disabled artistic practice. It also shows me attempting to grow comfortable using my body in live performance, which I have historically avoided due to the nature of my disability.

As always, we appreciate you sharing your insights and we’ve got a few more questions for you, but before we get to all of that can you take a minute to introduce yourself and give our readers some of your back background and context?

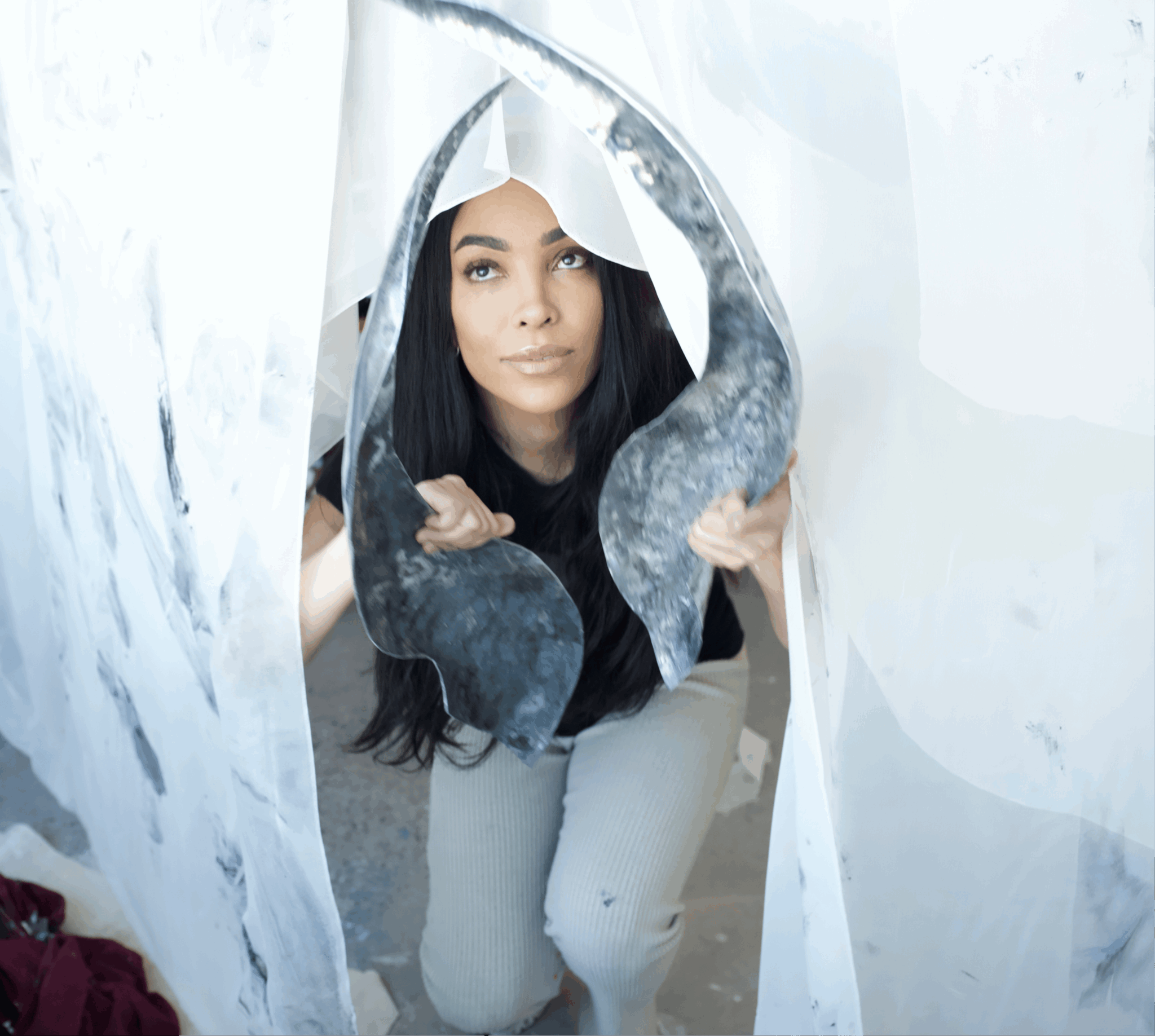

I am a Jamaican-born interdisciplinary artist based in New York City. My work spans painting, sculpture, installation, and performance taking up topics related to self-portraiture and familial memory, in tandem with abstraction. Using materials with symbolic histories such as chiffon, gauze, lace, hair weft, metal, and found objects—all of which carry historical resonance quietly embedded in Jamaican culture, domestic life, and architecture—I emphasize the female body as an architectural form. In that form, I see a site of strength, comfort, and bravery but also fragility and impermanence.

Since I was a young child, I have always had an interest in art and making things with objects around me. My mother was a teacher and my dad was a graphic artist, and both were artistic in their own way. I think I became an artist because of my dad. He would give me drawing pads, pencils, coloring books and paint as gifts, and I’d draw, color, and fill up the books with my art. I also enrolled in art classes in high school, but then took a break from it while completing my undergraduate degree at the University of the West Indies and pursuing a career in social work thereafter.

After visiting New York in 2014, I enrolled in summer classes at the Art Students League of New York and was intrigued by the rich history and the community of student artists and instructors. I took drawing, painting, and color design classes with Ronnie Landfield who encouraged me to apply to the four-year certificate program at the ASL. I moved to New York in fall 2015 to begin my artistic journey at the Art Students League. My program ended in 2019 and a few months later started working from a studio space in Midtown. During this time, I had my first solo exhibition and was included in a few group exhibitions.

Today, I am nearing the end of my MFA at Pratt Institute. I am filled with curiosity and a particular purpose to continue to hone and develop my practice. It is funny because at this point in my career I feel like I am required to have things resolved and give answers about what I do and why I do it, but I have more questions than ever before. I am on this quest to ask myself the tough questions and to take risks in order to find the answers.

Let’s talk about resilience next – do you have a story you can share with us?

My life underwent a drastic change when I turned 19 in 2009. One morning I woke up and realized I had suddenly lost my voice. No matter how hard I tried, I couldn’t speak clearly. For six years, I had no idea what caused my voice to stop working. But eventually I was diagnosed with Spasmodic Dysphonia, a rare neurological voice disorder that causes the muscles of the larynx to spasm involuntarily. I had lost control of my own body and my ability to express myself. Before my voice had difficulty functioning, I was quite outspoken. But that traumatic change in my body—and with it my ability to socially interact with others—became an extremely taxing daily challenge. Being unable to speak made me antisocial and withdrawn from my peers for most of my early adulthood. Losing the ability to control vocalizations forced me to see the world around me differently. I became more aware of my body as well as its functions and limitations. I also became fascinated with what I could learn from my body simply by listening to its needs. As a result, I became more aware of its uniqueness, weirdness, and capabilities.

Is there mission driving your creative journey?

Looking back, it’s clear that viewing my body as a site of information and experience also drew me closer to abstraction as an aesthetic paradigm. I thought of myself as different—a layered composite of beautiful and grotesque features. I realized that there are things my body does which I have no control over. And I learned that our bodies fail us while they make us feel alive and resilient in hopeless situations.

Searching for a way to speak without speaking, I began to see my art as an expression of the voice that had become stifled in my body. I also began to see deeper connections to identities that helped illuminate aspects of my life that I previously did not have language for. Studying queer artists, artists working with disabilities, and artists working in untraditional ways, I saw that I was searching for women who had taken up similar questions about how to express themselves even when they were silenced.

In turn, my work became a material investigation of how these came to speak through various modes of care, silence, and acute observation. Inspired by my female family members who were the root of my social life, I saw that I was not alone in having to accommodate challenges and significant change. With my own family in mind, I began seeking out my artistic lineage—the artists who would guide my development and help me conceptualize my own visual language.

Lately, my work has mediated on erasure and resurrection, and what these concepts mean within my practice. I think about my experiences within my gendered female body that ties into my maternal lineage and the generational trauma of being a woman. What does it mean to be a woman, to be physical matter, to be a body, to be a body with material needs and which can too easily be reduced to an object? And what happens when that feminized body is no longer?

Questions like these energize my practice and keep me busy in the studio, but they also give me a deep sense of connection to the world around me as well as the people in it.

Contact Info:

- Website: https://www.danamariebullock.com/about

- Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/danamariebullock?igsh=cTZsZ3IzZHFwaG04&utm_source=qr

Image Credits

Photo credit to Federico Savini