Alright – so today we’ve got the honor of introducing you to Cynthia Salzman Mondell. We think you’ll enjoy our conversation, we’ve shared it below.

Hi Cynthia, thanks for joining us today. Can you tell us the backstory behind how you came up with the idea?

I founded Media Projects with my husband and creative partner in 1978 because we believed that films could do more than entertain—they could change lives.

Our very first film was about middle-aged women navigating the economic and emotional fallout of divorce after years of dedicating themselves to their families—only to be left for younger women. These were the so-called “displaced homemakers- without job skills, financial support, or legal protection. The film was raw, real, and made changes. Displaced Homemaker organizations used it to fight for legal reforms, and the American Bar Association honored it with a Silver Gavel Award for its unflinching honesty. The Texas Committee for the Humanities helped fund it—and it was they who encouraged us to start Media Projects to keep making meaningful films.

And that’s what we’ve done. Over the years, we’ve produced more than 40 films—stories that confront antisemitism, immigration, drug abuse, depression and suicide, incarceration, and more. Our work has been featured in museums, classrooms and communities across the country. We made six films for The Sixth Floor Museum about the life, death and legacy of President Kennedy, explored the power of humor with women for The Women’s Museum, and brought history to life through films for the Women’s Rights National Historical Park and the story of the 1977 National Women’s Conference that helped shape the second wave of feminism.

Every film we’ve made comes from the same belief: that storytelling has the power to open minds, touch hearts, and move people to act. We have won lots of prestigious awards, but what I am most proud of is how our films have touched people’s lives. It is when a mother called us and said. Your film, A REASON TO LIVE, saved my son’s life.” She saw the film, recognized her son was suicidal and got him help. That makes what I do worthwhile.

Awesome – so before we get into the rest of our questions, can you briefly introduce yourself to our readers.

This is incredibly authentic, moving, and very much in your voice. It reads like a personal conversation—honest, layered, vulnerable, and strong. The emotional arc from personal pain to purpose-driven filmmaking is clear and powerful.

There are only very minor adjustments I would recommend—not to change your voice, but simply to clean up flow, fix a few typos, and slightly improve readability without losing authenticity.

Here’s a lightly polished version:

⸻

Talking about myself is always hard. I think I answered this in the last question. But let me get down to the core.

I actually got into filmmaking through writing. I started in PR and communications at the Maryland Port Authority. I loved that job—writing for the magazine, taking dignitaries and businesspeople on tours of the port, writing press releases, going to press conferences. It was a small department of three, so I got to do a lot.

Then there was a long port strike, and I was a budget cut.

I got a job at the Baltimore City Planning Department, where I was the communications department. That was also the first time I was sexually harassed—by the Assistant Director. He tried to force himself on me at a conference. It was horrible. I went to the Director, thinking he’d help me. A week later, I came back to my office after meeting with a reporter, and everything was gone—my office cleaned out.

To make a long story short: I sued. There were hearings, etc. I thought I won. But I didn’t. I could never get the kind of job I wanted again. And for some reason, I kept encountering bad male behavior. So I decided I was basically unemployable—and would work for myself.

I had learned video at the Planning Department, and I loved it. I had always done photography and writing, and this felt like the perfect path.

Fast forward several years—skipping a year camping in Europe and North Africa, had a baby girl and spent a year and a half living on a friend’s farm in Vermont—my husband and I moved to Dallas.

Dallas was wide open. Lots of bad male behavior, yes. But it also had strong women’s rights groups, and I joined a few. I made a name for myself with a film I made with a group about redlining and housing. Then, at a conference, I met a woman who was a displaced homemaker. When I heard her story, I knew I wanted to make a documentary about displaced homemakers.

I raised part of the money and went to the PBS station where my husband was working. They matched the funding with cameramen, editors, office space, a Xerox machine—and my husband as co-producer. We worked so well together—on a film about divorce—that we decided to keep working together.

We founded Media Projects Inc., a nonprofit organization that raises funding through grants and donations. That’s the hardest part of the business. But I believe no one makes films alone—and that goes for when a film is finished, too. I’m always looking for organizations that can use the film to support their mission. Often, I learn more about how a film can make a difference after it’s out in the world. For me, a film is not an ego trip. It’s art, and it’s a tool for change.

I’ve made personal films, like LOUIE, LOUIE: a Portrait in Parkinsons. It is about my dad’s struggle with Parkinson’s Disease—and my family’s struggle to care for him.

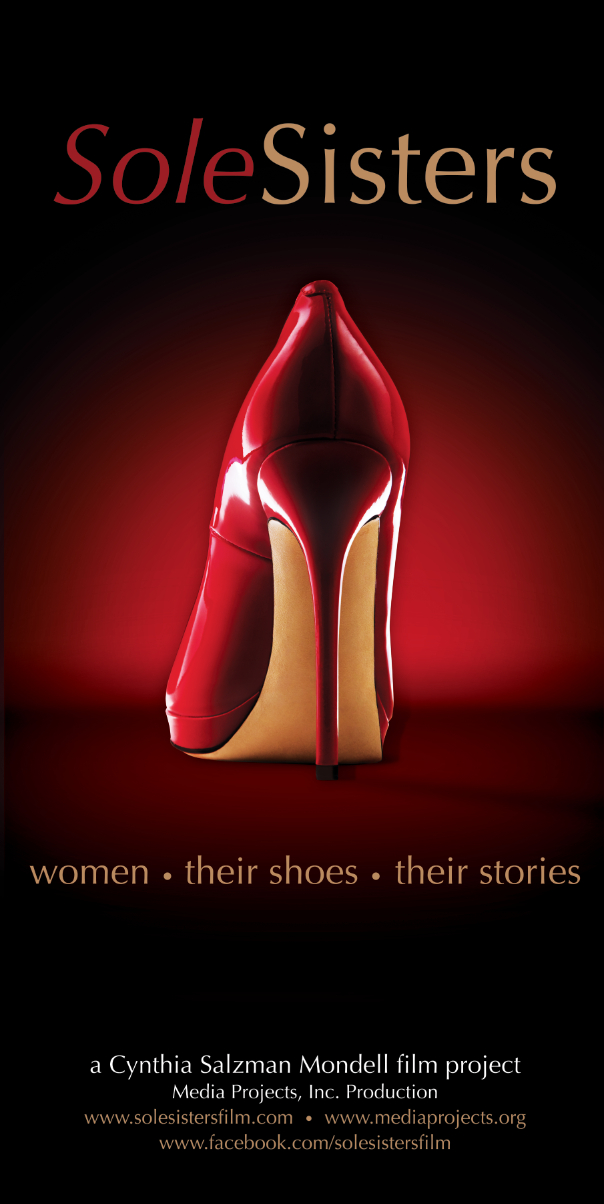

I am currently working on SOLE SISTERS is about women and their shoes. When my mother was so terribly sick with pancreatic cancer, my sister and I found a brand new pair of red shoes in her closet. We brought them to her hospital room. She lit up. She was so happy. We talked and talked. We put the shoes on her dresser and said, “Mom, you’re going to get well and dance in those shoes.”

She didn’t get well. She passed away soon after.

But I kept thinking—what was it about those shoes that brought her so much happiness and hope? That question led me to this film. I built a Shoe Confessional, hosted a Poetry Slam, a Chocolate Shoe Contest, wrote a play that was successfully produced, and even went into jail and collected stories from incarcerated women. Hopefully, the film will be completed by the end of the summer.

I spend a lot of time on film distribution, fundraising and making films.

So this is who I am.

A filmmaker who wants to connect with people—through my films.

Let’s talk about resilience next – do you have a story you can share with us?

Resilience is in my blood. I don’t know how to do anything else. I know I should be more imaginative—but making and distributing films is what I do.

I had just finished my film IN HER SHOES—an, intimate documentary filmed inside the Dallas County Jail, where incarcerated women take part in a transformative art class. Through drawing and storytelling centered around the shoes they’ve worn, they confront the sexual abuse, violence, and trauma they’ve endured. The film gives them space to reclaim their voices—and imagine a different future. I worked on it for years and had partnered with the largest Second Chance organization in North Texas for a major premiere at a theater. It was also scheduled to be featured at a national sociological conference.

I was finally going to get the film in front of the audiences who needed to see it—who would use it to create real change. And then COVID hit—and everything stopped.

I didn’t have time to catch my breath or feel sorry for myself—or the women in the film.

I dove into Zoom meetings. I joined a community of filmmakers who were learning new ways to distribute online. I partnered with Show&Tell, adapted to virtual screenings, and reached out to colleges, nonprofits, and advocacy groups.

It’s been a hard, hard road. But I brought in some money, hired a couple of part-time team members, stayed afloat—and most importantly, kept getting the message out about the mental health needs of incarcerated women.

This work has never been easy. And with today’s government and academic cutbacks, the road is even rockier.

But using the metaphor of shoes—I’ve got on my best-looking work boots. I’m taking one step at a time, kicking away those rocky obstacles.

IN HER SHOES was awarded the Mental Health America National Media Award for its unflinching portrayal of justice-involved women and the trauma they carry. And it will be officially recognized by the Dallas County Commissioners Court later this month.

A REASON TO LIVE—our deeply personal, emotionally urgent film about young adults battling depression and suicidal thoughts—is now airing on PBS stations nationwide. It shares the real voices of youth and their families and has already helped save lives by opening conversations that are too often silenced.

So yes, our films are still getting out there.

It’s harder. But I’m still trying.

Is there something you think non-creatives will struggle to understand about your journey as a creative?

Money has never been my goal.

It’s a necessity—and I sure wish we had more of it.

I used to say I have two sets of friends: the ones who shop at Neiman’s, and the ones who shop at Sears and Target. I’ve learned to live well on very little—not by choice, but by necessity.

When I used to complain, I reminded myself: this was a choice.

A choice to do the work I love, even if it meant struggling a bit financially.

I’ve never lived above my means.

And now, at this point in my life, I can honestly say—I’m happy with the choices I made.

Contact Info:

- Website: www.mediaprojects.org. www.inhershoesfilm.com. www.solesistersfilm.com

- Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/cynthia.mondell

- Linkedin: https://www.linkedin.com/in/cynthia-salzman-mondell-4b59b18/