We’re excited to introduce you to the always interesting and insightful Clive Knights. We hope you’ll enjoy our conversation with CLIVE below.

CLIVE, appreciate you joining us today. What’s been the most meaningful project you’ve worked on?

That would be founding a new school of architecture. The story began with my appointment at Portland State in 1994 under the auspices of an agreement to start a joint professional Master of Architecture program in Portland in partnership with the other university in Oregon (which shall remain nameless) that was already teaching architecture down the valley. After a year or two it became crystal clear that the other university, with its long-established architecture program, had absolutely no intention of partnering with a fledgling program like ours at PSU, with our 3 faculty against their 30 or so faculty. So, we kicked them off our Portland campus and they dutifully spent the next decade maneuvering within state politics to make sure we were never given permission to start a Master’s program. A full inventory of the ugliness of humanity was directed toward us in many different forms of arrogance and derision that took us by surprise, so adamant were they that their monopoly on state funded architectural education would endure without competition.

Nevertheless, we persevered by building up the reputation of our undergraduate architecture program (which they could not oppose since it did not need state approval) until in 2007 something quite miraculous happened. Several leading figures in the upper administration at both institutions changed simultaneously, stars aligned for literally one year and permission for PSU to offer a Master’s program was, unexpectedly, not opposed. I, coincidentally, became Chair of the school that same year and off we went riding headfirst into the rigors of a five-year professional accreditation process. Readers might not know but in the USA if graduates of any architecture program wish to become licensed architects they must study at a school accredited by the national professional accreditation board, NAAB. We commenced our Master of Architecture in 2009 and accomplished initial accreditation in 2012. Since then our students have become the most awarded of any institution in the American Institute of Architects consortium of Pacific Northwest Schools from Idaho to Hawaii in their annual student design awards, an achievement we are especially proud of as the youngest school in the region. We are now 12 faculty deep, we offer both a 2- and a 3-year M.Arch as well as 2 graduate certificates and we are one of the leading schools in the country practicing ‘public interest design’ for underserved, disadvantaged communities across the world.

As for the pedagogy of the school, it is heavily influenced by the phenomenological tradition in philosophy and so focuses less on the aesthetic of the architectural object and more on the human experience, including the embodiment and interpretation of cultural meaning in works of architecture. I hired all but one of the current faculty and aimed at gathering a team that was sensitive to the over-arching direction of the school set in place by me, while they each brought unique research and creative perspectives to the educational experience of our students. We are also quite adamantly and proudly a ‘thesis’ school which means that the final year of graduate study is dedicated to a student’s own creative agenda which we assist them in articulating and advise them as they execute it. This experience is invaluable in shaping the values that a graduate takes out into the world of practice with them, values pertaining to humanity that can sustain an ethics and a purpose beyond a mere functionary contribution to the commercial and expedient demands of most architectural firms.

It is a sad indictment of contemporary society that very few people actually pay attention to their architectural surroundings in their everyday life, but if they did they’d find various levels of banality generated predominantly by forces of expediency and technological convention. Many people have forgotten that architecture is an art, in fact it’s the most public art, it’s also the art that lays down the configuration of space in which all the other arts can take place. Unfortunately, not only have the other arts been sequestered to specialist environments removed from everyday life (the gallery, the museum, the concert hall, the theatre, the movie house, and so on) but the arts, including architecture, have forgotten how to converse with each other out in the open, how to contribute to the enrichment of life in our cities, to civic space, through collaboration in engaging the common narratives of the communities in which it emerges. Our school set out to change that sensibility, to put graduates into the world who are poets in the art of architecture.

CLIVE, love having you share your insights with us. Before we ask you more questions, maybe you can take a moment to introduce yourself to our readers who might have missed our earlier conversations?

I won my first drawing competition at the age of eight, a big sterling silver cup, at a local village festival in rural Kent, England. I loved to draw more than anything else as a child and though I learned to read at a very early age, so my Mum likes to remind me, I hated books all through school and only read what was absolutely necessary to get through classes. As a result, I performed miserably in most everything at high school but I am forever grateful to my insightful art teacher who could see where my passion lay, in drawing. Back then I drew a lot of surreal objects and interior settings and it was he who suggested applying to architecture school, I guess, seeing some promise in those crazy fantasies.

To cut a long story short, in the 1980s I completed both undergraduate and graduate professional design degrees in architecture at Portsmouth Polytechnic, and then a Master of Philosophy degree in the history and theory of architecture at Cambridge University with the incredible professor Dalibor Vesely. Right after that I got my first full-time teaching position at Sheffield University and stuck it out there for six years until I emigrated to the USA on New Year’s Day 1995 to join the art school in Portland, Oregon. Frustrated by the anachronistic attitude to architectural education at Sheffield and their disinterest in innovative pedagogy, I had to find new pastures. Portland State University made me an offer I couldn’t refuse, to start a brand new architecture school, a dream proposition for any young, ambitious teacher. The summer before taking the job my partner and I drove across the full breadth of the States twice, east coast to west, then all the way back again, just to be sure we knew what we were getting into.

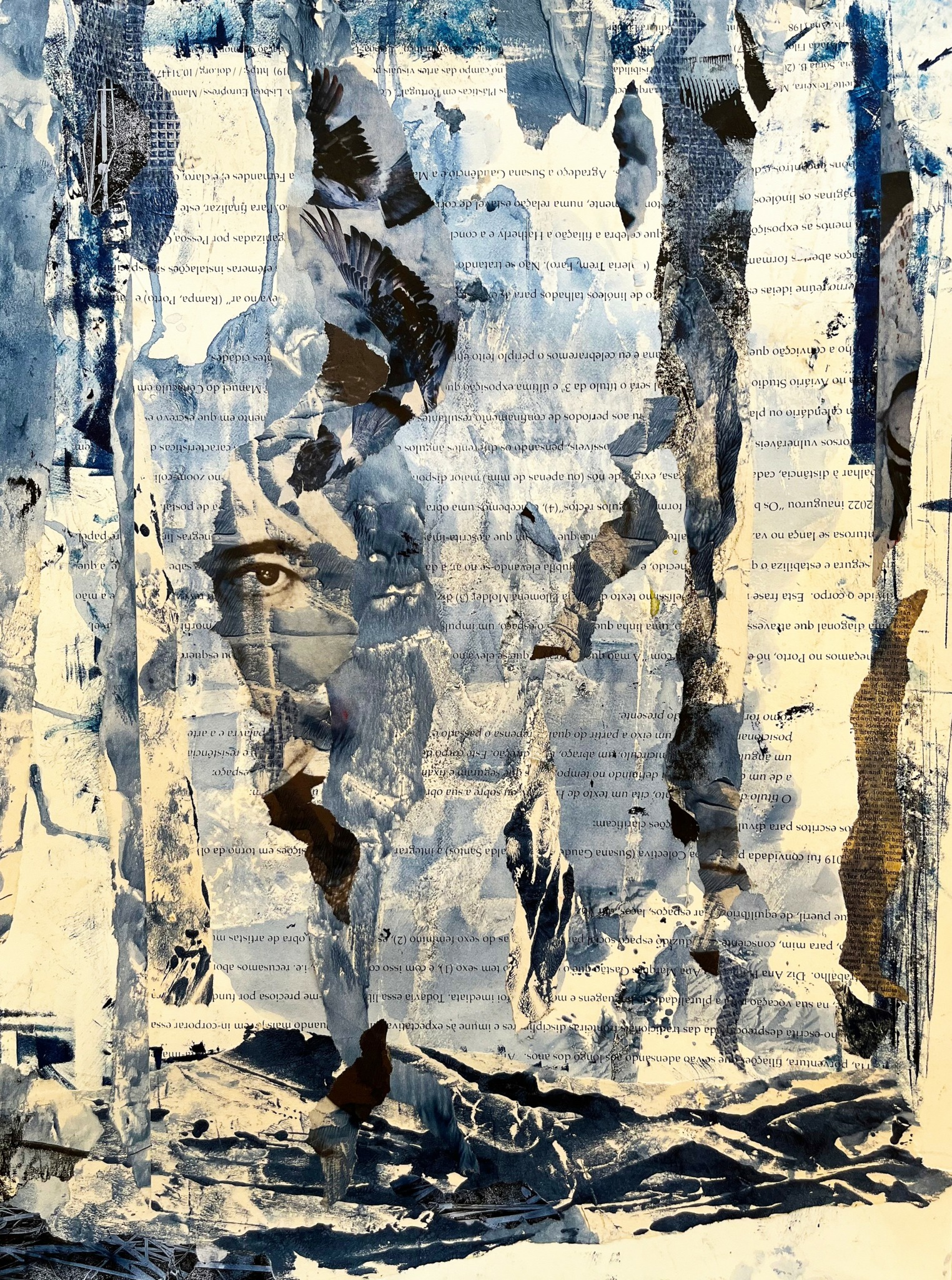

I had always taught collage as part of my design studio pedagogy at Sheffield and moving to an art school opened up such creative freedom that I’ve been able to nurture my love for the genre with increasing levels of intensity and focus over the years. My first collages were ransom note style posters for student organizations I belonged to at college. Then I made collage a significant aspect of my master’s thesis in architectural history and theory as I studied the symbolic aspects of ancient Roman dwellings at Pompeii and interpreted my discoveries in a series of collages that were later published by Routledge.

In 1985 I was fortunate to exhibit 3 design projects at the Third International Exhibition of Architecture at the Venice Biennale with my three collaborators at the time, right after graduating from architecture school. We were in our mid-twenties, had just set ourselves up in practice together and thought we’d hit the jackpot. At that time, we also won a couple of international architectural design competitions and were published in the architectural journals but then… silence. No commissions came rolling in as we’d expected and after 3 years we dissolved the practice. I went to Cambridge University to study architectural history and theory and my former partners found teaching positions in architecture schools.

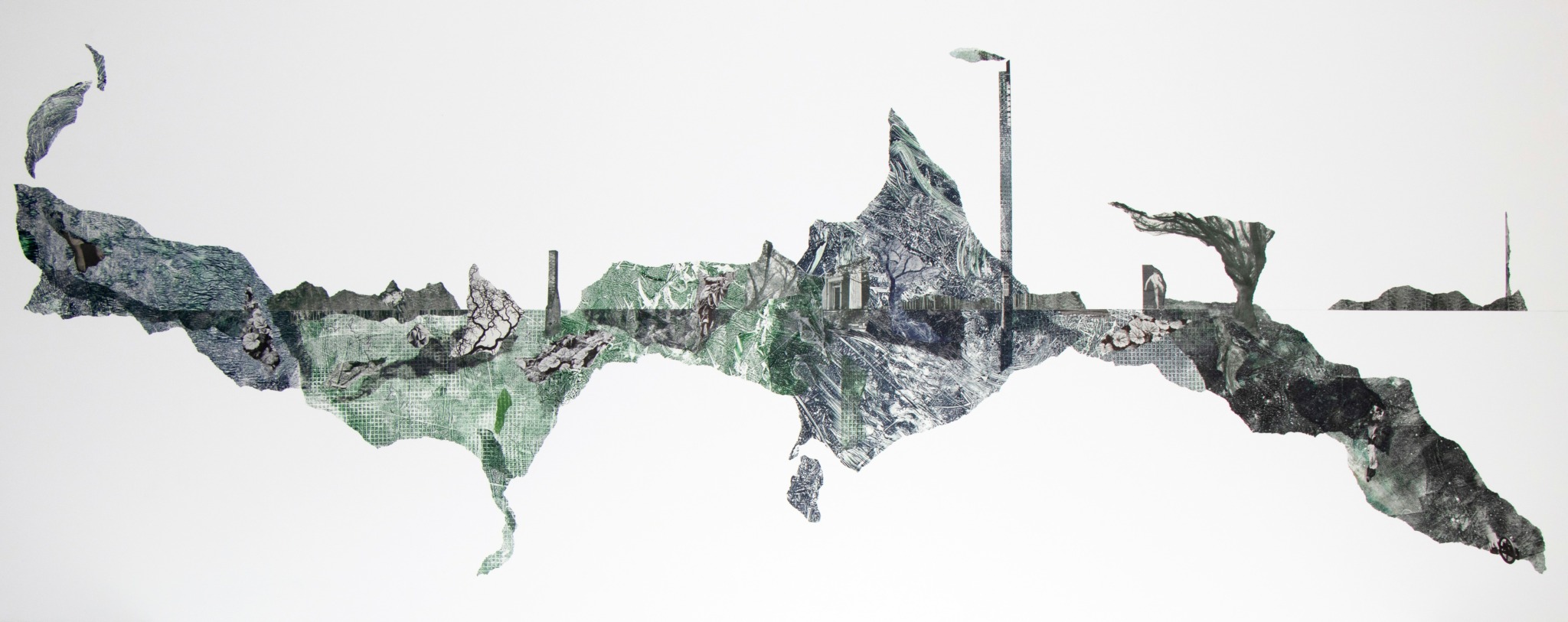

Fast forward to September 2021 and my first solo exhibition of collage work at Laura Vincent’s gallery in Portland and I’d have to say that I was most surprised and encouraged by the reception of the work, and that much of it sold. So, memorably, it would be Laura’s confidence in my work and the gamble she took in showing it, especially when the perception of collage in the commercial art world as a genre is notoriously ambivalent, if not disinterested, that I have much gratitude for. I have had 4 solo shows since that first one, two more in Portland, one in Rome and another in Williamsburg, Virginia. These experiences have generated a more disciplined approach to my productive process as deadlines will tend to inspire. Also, thinking in terms of a ‘body of work’ with an overarching theme has been a novel experience, the collection or series that can bring cohesion to multiple pieces. I had never really explored this a great deal before, and the challenge has been exciting. My first monograph Gestures from a Body at Work: Unsuccessful Attempts at Grasping Eternity (available from Lulu.com) gave me the opportunity to search out common themes across the recent body of work in my archive and to group these works into the six chapters that form the book.

At this stage in my career, collage has overtaken architecture as my primary love and I’d like to be doing it full-time, despite my love of teaching. I am currently working on this transition so we’ll see where it all leads. Opening a small gallery in Northern England or Southern Scotland dedicated to showing the work of collagists from all over the world is part of the dream for this next phase of creative endeavor.

Learning and unlearning are both critical parts of growth – can you share a story of a time when you had to unlearn a lesson?

Architects are taught to control everything and much of my recent creative life has involved a concerted effort to unlearn that need for control and to release myself to imaginative play.

I invoke the wisdom of the great German hermeneutic philosopher Hans Georg Gadamer when speaking of beauty where he reminds us of the importance of ‘play’ in the pursuit of art. Play is not frivolous, genuine play is about imaginatively participating in a situation in which one did not make the rules. Play in life begins with the creative engagement with the orders of bodily necessity – the need to breath, to seek nourishment, to rest, to be cleansed, to procreate, and so on – amidst the orders of the cosmos – the passage of the sun, the moon, the night sky, the cycles of the seasons, the movement of water, the shifting of topography and so on.

The play of paper fragments in the making of a collage is never about control and logical processes. It is more like a conversation, a call and response whereby each member of the population of fragments strewn across my work desk calls out to be included in the ensuing conversation, to participate in, and influence, the direction and thematics of a work as it unfolds beneath my hands. My work is never an introspective search, it aims always to be an outward gesture of participation in the context of cosmic and human events in which I find myself. Ripped and torn paper pieces are my accomplices, my partners, my interlocutors.

Have any books or other resources had a big impact on you?

I studied philosophy at Cambridge and the fields known as phenomenology and hermeneutics have continued to fuel my sense of purpose in my creative endeavors. In my twenties I was desperate to understand what human creativity was all about, why it exists and how we do it best. Philosophers like Merleau-Ponty, Gadamer and Ricoeur provided me with the most convincing answers by pointing to the unique and unsubstitutable human activity of ‘poetic making’, essentially communicating to each other about what the world is like, using metaphors. Metaphor is the essence and vitality of all worthwhile communicative acts, all language, worthwhile in that they reveal something ‘as’ something else, through the recognition of likeness. It is only through sustaining this activity of seeing likeness in difference, that we can form agreements about the world around which to gather as a community.

My favorite essay from this body of thought is Gadamer’s ‘On the Relevance of the Beautiful,’ still, to my mind, the most compelling assertion of the continued value of beauty and what is consists of, something we barely speak of these days, it seems, sadly.

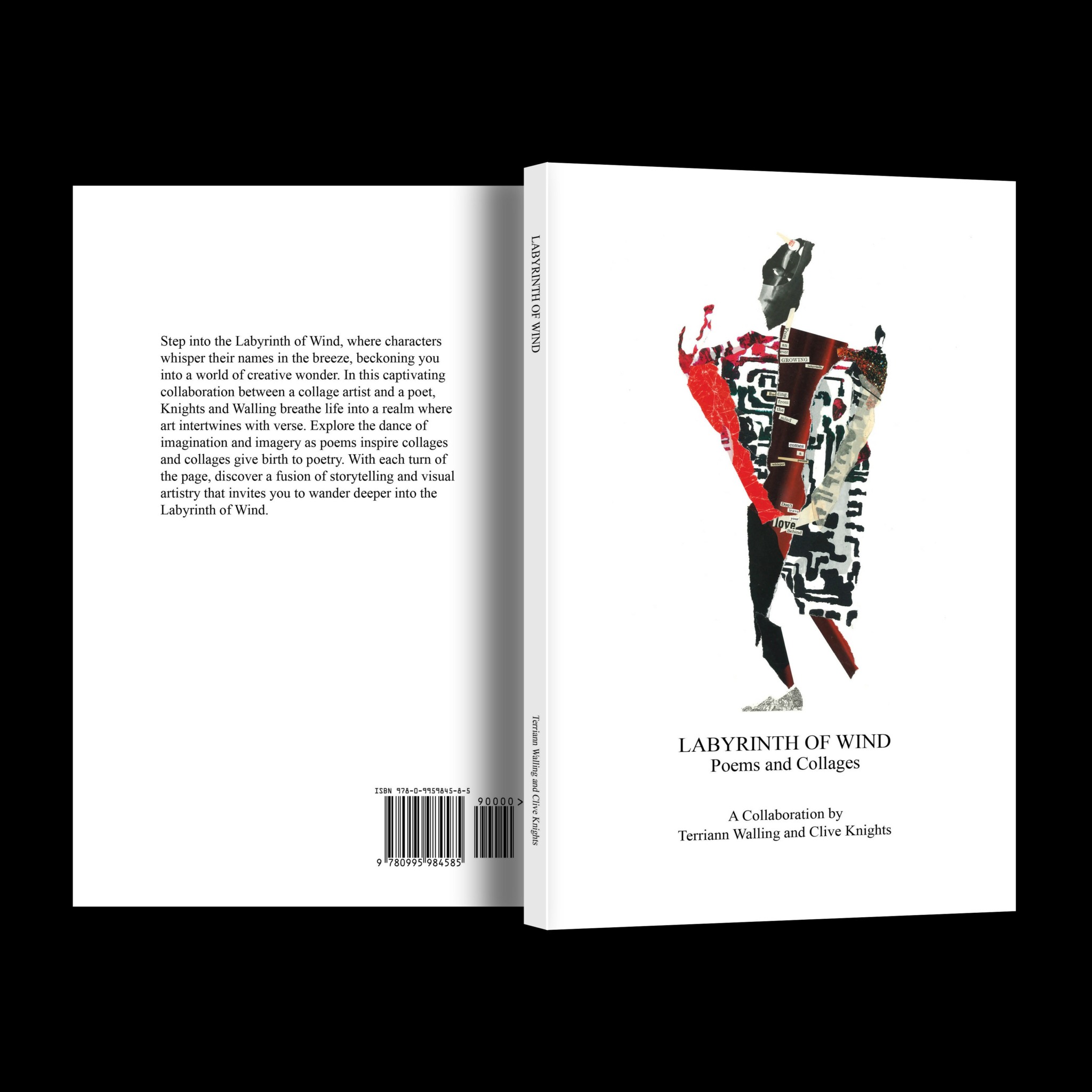

I must mention a collaboration that has just been published in book form titled ‘Labyrinth of Wind: Poems and Collages,’ created over the past two years with the wonderful Canadian poet Terriann Walling. We met in July 2022 at the Chateau d’Orquevaux artist residency in France and over the last 2 years have generated a unique creative collaboration in which 52 original poems are paired with 52 unique collage characters that form a magical community trapped inside a mythical labyrinth. The creative interpretations unfolded in both directions with poems inspiring collages and collages inspiring poems, and in one instance, Boatman, we crossover disciplines. The poems and collage characters offer strange, thought-provoking insights into the vast array of beautiful idiosyncrasies found in human nature, fragments of each we often discover in ourselves when we least expect it. The 120-page full-color book is now available on Amazon.

The value of collaboration cannot be over-stated, especially cross-disciplinary collabs, because each partner is challenged by creative questions framed in ways they would never imagine themselves. I highly encourage everyone to try it out. The pride one feels in the outcome of collective efforts is special indeed, mainly because it is shared, it hangs in the open space between the two of you, not lodged inside the singularity of private experience… and that’s beautiful.

Contact Info:

- Website: https://www.cliveknights.com

- Instagram: @knightsclive

Image Credits

Clive Knights