Alright – so today we’ve got the honor of introducing you to Christopher Huizar. We think you’ll enjoy our conversation, we’ve shared it below.

Christopher, thanks for joining us, excited to have you contributing your stories and insights. I’m sure there have been days where the challenges of being an artist or creative force you to think about what it would be like to just have a regular job. When’s the last time you felt that way? Did you have any insights from the experience?

Being an artist doesn’t always align with how society operates, so it sometimes works against “happiness.” For instance, I’ve often chosen creative endeavors and education over pursuing “regular jobs.” This has just been part of my creative journey, which is a journey filled with internal conflict and ongoing self-realization. I wouldn’t necessarily call all of this “happiness.” But I will say that it doesn’t always feel like a choice.

As an artist, the impulse to create is a compelling one. I was recently talking to a friend about various projects, and she asked me, “Do you do something creative every day?” I thought about it for a moment. Whether I’m writing, working on an illustration, playing guitar, or singing made up lyrics over a song, there is always a creative mode of expression at my fingertips. “Yes, actually” I said to her. “Everyday.” Furthermore, and I suspect this is true for many artists, if I go a day without doing something creative, I feel it. I can feel the drag of my body in space and the weight of worldly obligations pressing down on me. It’s a stagnant and unsettling feeling. Whereas pursuing the creative impulse gives me an immeasurable feeling of fulfillment. I don’t know if that is “happiness,” but it without doubt feels like a sense of purpose and worth.

Well, I’ve had “regular jobs.” I think most artists have to at some point. “Regular” being fast food or bartending, roofing, teaching, or working at a bowling alley. All of which I’ve done. Usually, jobs that didn’t pay much but allowed me some free time for creative endeavors. The tradeoff of creativity for financial security has been an ongoing negotiation for me.

When I was an art instructor in Oregon, I had a steady job with enough free time to develop my art. Then I moved to Oakland where I worked as a full-time graphic designer and became a parent. Financially speaking, the Bay Area is not an easy place to get by, and I found myself working two graphic design jobs. One was a full-time job and the other one was part-time. Between those jobs and being a parent, my creative endeavors had shifted primarily to illustrating personal projects. Mostly because it required minimal space and tools to execute.

When my child was born I realized how narrow the window suddenly was for me to pursue graduate studies. Once my kid was old enough to be in school, it would be more difficult for me to move around the country. So, after a few years in Oakland I left both of my jobs and relocated my family to Chicago, where I studied performance art. While being in school was creatively enriching, I was also helping raise a child and working at a toy store in a mall. These were difficult endeavors to be simultaneously committed to.

To paint a little picture for you, it was the type of toy store that sold giant plush unicorns and donuts, hotdogs and corgis. Basically, any animate or inanimate object you could slap cute eyes and a little smile onto. They were the kinds of oversized colorful prizes used to tantalize suckers at carnival booths. Or malls.

My job there was to re-organize toys after customers would come through and mess up their presentation. I would make sure the toys were positioned upright and facing forward in their cubbies, which lined the walls, ceiling to floor. The result was full walls of colorful cute plush toys staring out at you. This is a job I performed with a fine arts degree, a decade of experience teaching in upper education, and a background as a graphic designer. My eyes had been trained to measure the relationships of adjacent colors and to trace the contours of beauty. My hands were strong and adept at manipulating blocks of clay. Like Alexandre Cabanal tenderly laying Venus onto a bed of hair tendrils and sea foam, I would precisely position a stuffed avocado in its cubby, just so, until its eyes filled with life. It wasn’t a job that paid well enough to support a family of three, and it wasn’t a job that brought me happiness. But it did help keep me afloat while I studied and while I looked for work after graduating.

After finishing school, I applied to any job I could find that was within a creative field. But living in a major city that was teeming with artists and designers made it difficult to get on anyone’s radar. Because of my familial responsibilities I had to refuse job offers that didn’t include health insurance, as well as those that expected overtime work without overtime pay. And yes, these were expectations that were clearly stated by employers during interviews. About six months into the job hunt my partner suggested it was maybe time that I get an application at the Home Depot near where we lived, and that I focus on getting a “regular job.” This felt like such a sharp departure from the creative and professional trajectory I’d worked so hard to create. I wanted to hold out for as long as I could. For something that I didn’t know. As a father trying to support his family, this was such a difficult position to be in. And it was difficult to fend off the creeping notion that leaving two salaried jobs to study performance art and work in a toy store had been a huge mistake.

A man and his child came into the toy store one day, to purchase a plush avocado. The father was wearing merch from a local theater that I knew had an open position for a graphic designer. I knew this because I had already applied for it twice over the previous couple of months. After some inquiry, I discovered that this person was the creative director in charge of hiring for that position. While attempting to present myself as much as a “creative professional” as is possible while standing in front of a backdrop of giant toys, I mentioned to him that I had applied for the job. He told me he’d look at my application… and there was a faint blip on the radar.

Despite my skepticism, he wasn’t lying. After successfully interviewing for the position, I was able to move from plush avocado salesman to graphic designer once again. It’s hard to think it was anything more than chance that finally got me on the radar. But I will say that the years of working at that theater in Berkeley, as well as the conviction to finding work in a creative field, were all puzzle pieces that didn’t fit together… until they did. Even though it’s creative, I still think of my job now as a “regular job.” But it’s one that shares some balance with being an artist.

Christopher, before we move on to more of these sorts of questions, can you take some time to bring our readers up to speed on you and what you do?

I suppose how I ended up working as a graphic designer is a little unexpected, given that I studied sculpture and performance art. In 2014 I was teaching video editing, animation, graphic design, and various other courses at an art college in Portland Oregon. While this was fulfilling, I wanted to make a transition into a profession that paid a little more than teaching. So, after ten years, I left my job to look for work in the Bay Area. My plan was to secure a job in San Francisco as a front-end web-developer, because it seemed like my most marketable skill at the time. I naively gave myself two weeks to find this dream job, after which I would move my partner and my belongings down with me.

After a month of scouring daily job listings and sending out countless applications, I’d come up empty handed. It seems I’d drastically underestimated the talent pool and competition for tech roles in the Bay Area. I decided to broaden my search to include the other creative skills I had. After three months with no luck, I was running out of funds and decided to fly back to Portland where I could assess my next move. After exactly one day back, I received a call from a space & science center I’d applied to. They called me on a Monday to ask if I could come in that Wednesday for an interview. They had no idea I was in back in Portland and I wasn’t about to risk creating any hurdles between myself and a potential job. “Of course!” I enthusiastically told them. I then scraped together what funds I could and bought a one-way ticket back to Oakland to land this job. Which I did.

This was my first full-time role as a graphic designer. Back on track with the original plan, I found an apartment near my new job and my partner moved down to join me. Then, after one week in our new home, in a new state, we found out my partner was pregnant. To prepare for this life changing experience I had to find a second job. This job ended up being part-time at a theater in Berkeley, and is where I learned about designing and marketing for theaters. In addition to my usual graphic design tasks, I was also able to use my painting skills to create show art. Actual acrylic paint, with brushes, on board… as part of my job.

When I got accepted into graduate school in Chicago, I had to leave both jobs. But skills I’d learned working at the theater made me an ideal candidate to be a designer at a Chicago theater. Despite my fine art skills, my job was to exist solely in the realm of graphic design. However, after just about a month and a half on the job, the pandemic hit.

Since theatre is generally dependent on people experiencing a production in person, and the pandemic prevented that very thing, they had to come up with ways to generate revenue during the pandemic. The theater quickly pivoted to producing streaming media that was created while socially distancing. This unanticipated new line-up of digital productions needed illustrations to market them. So, once again, I was able to assume the role of show art illustrator, and create posters for the radio plays Animal Farm and The American Clock. During this time I was also able to lead the animation of a ten minute movie titled The Red Folder, and devise interactive digital study guides for the production. The surprise pivot for me that came out of the pandemic, was being able create art as my job. And while that art needed to please various stakeholders, I was sometimes given full creative control over a final illustration.

In 2021 my partner and I separated, and we both moved back to Portland. Because I had been working remotely practically since I’d started at the theater, I continued to do so, only now from Oregon. My responsibilities at this job fluctuate some, but my fundamental role is still to design various marketing pieces. I design things like posters, brochures, programs, branding, and work on other projects as needed. I’ve even had the opportunity to paint a watercolor of the theater’s marquee, so that prints of it could be available in the gift shop. What people need to know about the work I create as a designer is that I look for an emotional connection first, then I strive to create things that are unexpected. But when anyone asks me what I do at the theater, I tell them that my job there is to create beautiful things. Which is what I do.

Learning and unlearning are both critical parts of growth – can you share a story of a time when you had to unlearn a lesson?

One lesson I had to unlearn as an artist is the idea that my ability to paint or draw, or manipulate materials, is what determines my artistic validity. I’ve spent a large portion of my life learning to do those things very well, but over the years I’ve learned that they are mostly just demonstrations of skill and technique. And while those are good things, they don’t necessarily represent my creative capacity, my ability to think abstractly, feel empathy, or make intellectual connections.

This lesson is embedded in the work of artists like Marcel Duchamp or Allan Kaprow, but for me to internalize this lesson meant letting go of something that felt fundamental to my identity as an artist. This lesson came from exploring improvisation and authentic movement. These practices are built on concepts like intuition, chance operations, and the serendipitous interactions between people, objects, and spaces. By their nature, there is no determinable control over the shape a performance takes. Therefore, each experience created through this process is born of its own organic evolution. No “good,” no “bad,” no “author,” but simply an experience of creativity manifest. And the value of that experience is unique to each person who witnesses it. Working in this manner helped me to see artistic validity as more intrinsic to the creative process than to the execution of skills.

What do you think is the goal or mission that drives your creative journey?

My creative journey is driven by a sense of play and my work is filled with humor. I had an art professor ask me one time what I would want people to say to me after seeing one of my performances. My answer to this was, “I wasn’t expecting that.” I’d want someone to need to pause while processing what they had just experienced. There is generally a protocol for how we experience art. Even if it’s unspoken, we have some idea of how to process art by certain standards, and how to speak about it.

I’ve always been a fan of programs like The Twilight Zone and of the fake commercials that used to play during Saturday Night Live. What I love about genres like weird fiction and parody is that they playfully subvert familiar structures. As an audience we understand the familiar vocabulary of these structures and therefore what we should expect from them. However, in these genres, that vocabulary can be confounded by the message being delivered. For example, we understand what to expect from the structure and vocabulary of a car commercial, but when the car is made from clay it exposes the structure delivering the message. Similarly, with humor, the strategy is often to set an audience up with a something familiar that they can anticipate, and then to knock them over with something incongruous to their expectations.

As for play, it is a skill that comes naturally to us as children. However, even though it is engrained in our nature, it is something we learn to suppress. Yet, like weird fiction or parody, play can be a means of subverting social impositions and expectations. That is, through play, one can reclaim their humanity from societal impositions that can be dehumanizing. Because of this, acts of play are acts of activism, and they remind us what it is to feel human joy. This is a big part of why play is important in my work.

Contact Info:

- Website: https://christopherhuizar.com

- Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/christopherhuizar

- Linkedin: https://www.linkedin.com/in/christopherhuizar

- Twitter: http://twitter.com/chuizie

Image Credits

Christopher Huizar

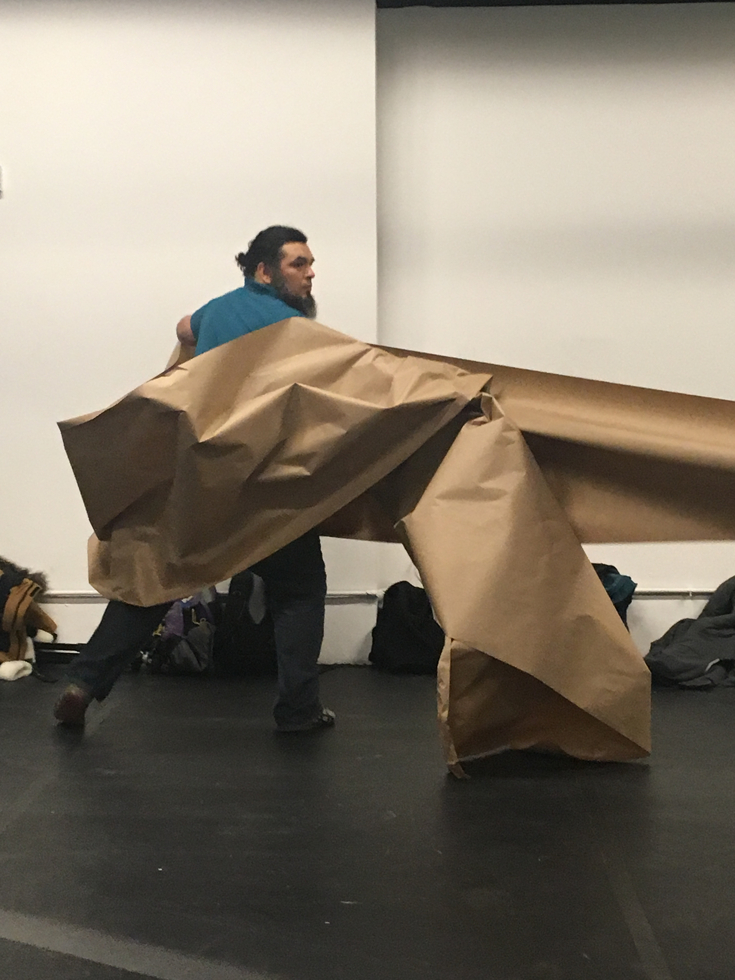

A Pat on the Back, 2019

Performance

Christopher Huizar

Hero, 2019

Performance

Christopher Huizar

A Home What Howls, 2024

Digital and traditional illustration

Christopher Huizar

Bald Sisters, 2023

Digital and traditional illustration

Christopher Huizar

Chlorine Sky, 2023

Digital and traditional illustration

Christopher Huizar

Handy, 2024

Tropical fruit punch gummy candy

Christopher Huizar

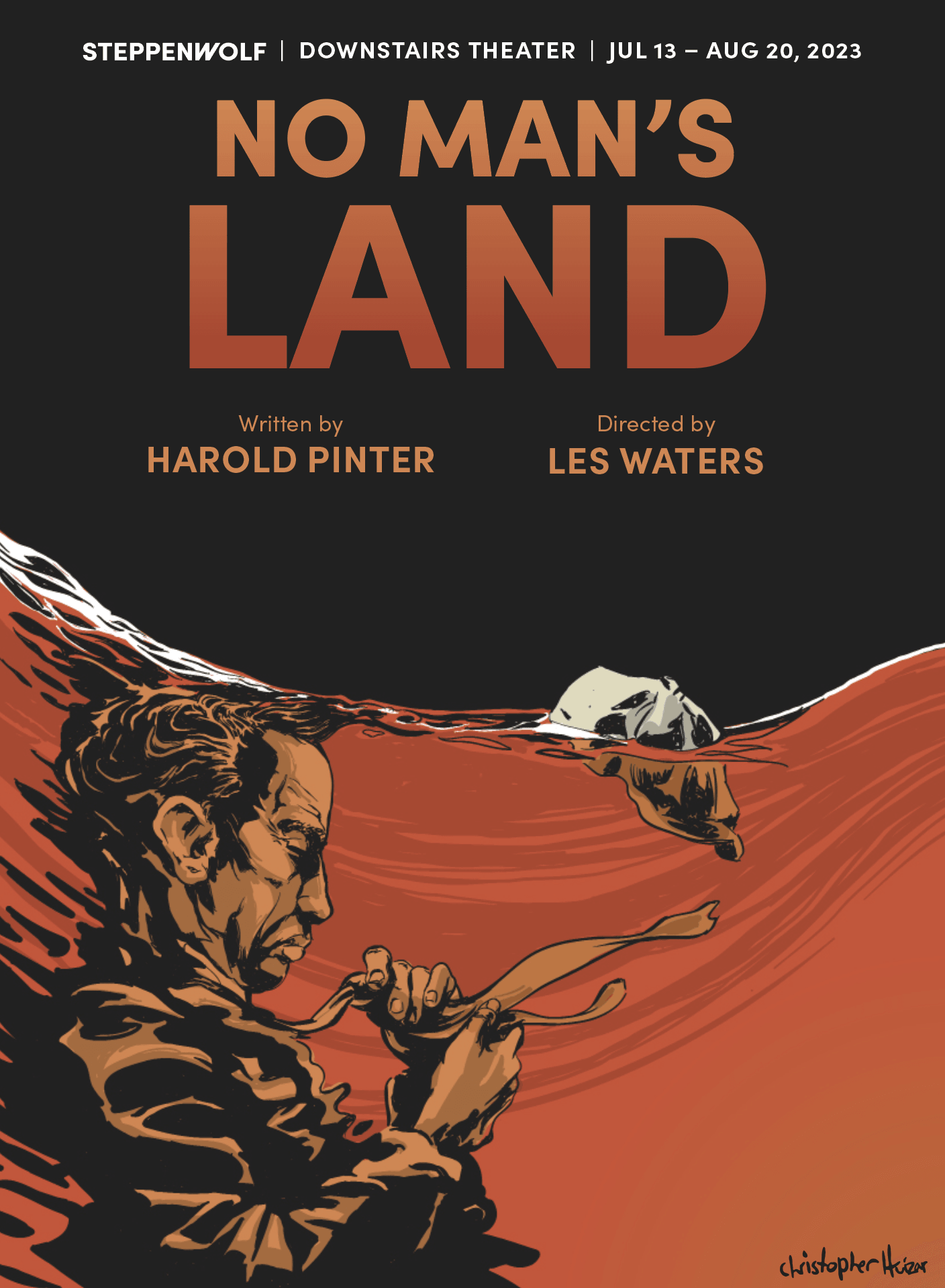

No Man’s Land, 2023

Digital and traditional illustration

Christopher Huizar

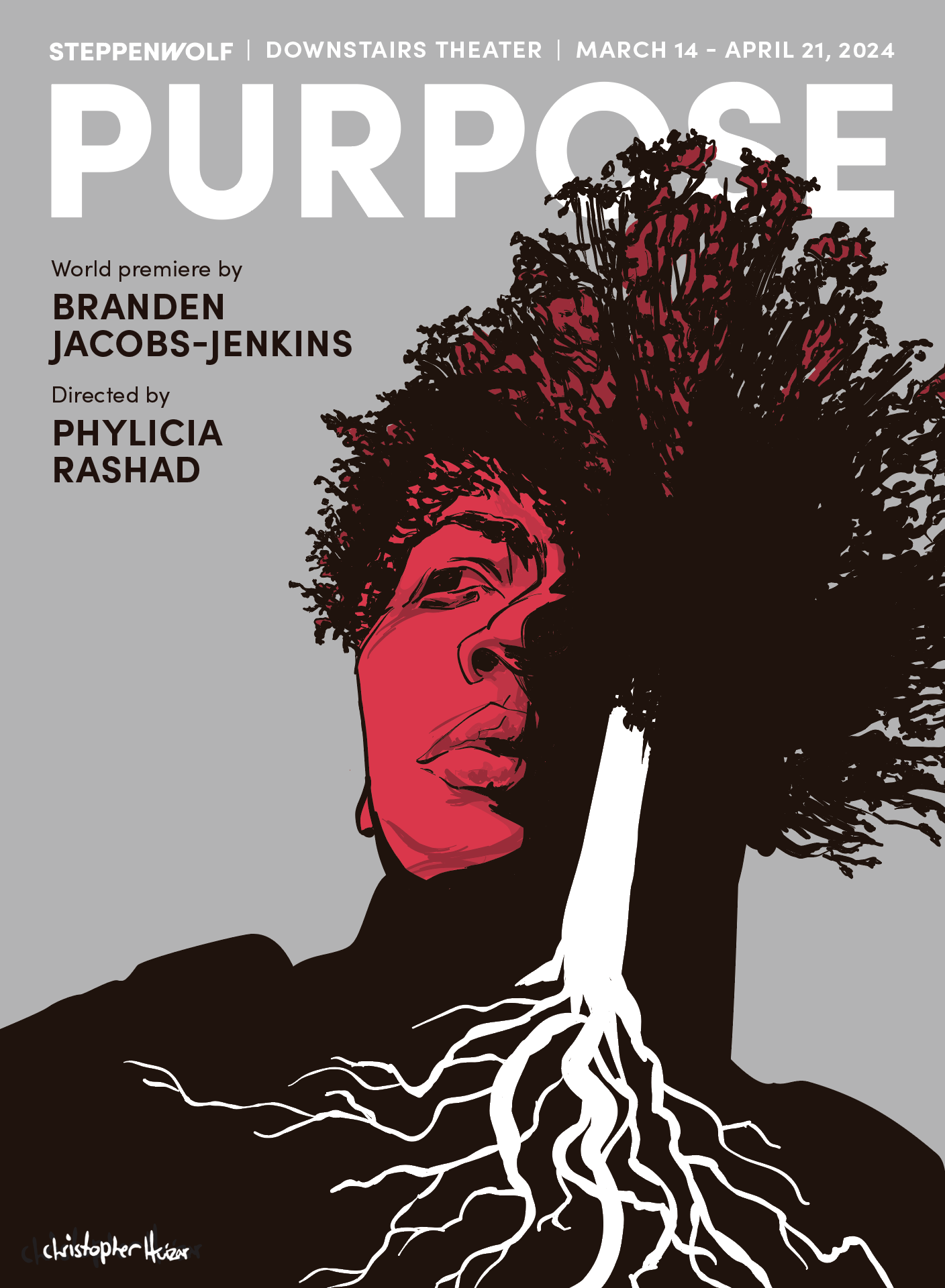

Purpose, 2024

Digital and traditional illustration

Christopher Huizar

The Birds, 2015

Digital and traditional illustration

Christopher Huizar

The Thanksgiving Play, 2024

Digital and traditional illustration