Alright – so today we’ve got the honor of introducing you to Chris Kempel. We think you’ll enjoy our conversation, we’ve shared it below.

Chris, thanks for joining us, excited to have you contributing your stories and insights. Let’s kick things off with a hypothetical question – if it were up to you, what would you change about the school or education system to better prepare students for a more fulfilling life and career?

What would you change about the education system to prepare students for a more fulfilling life and career? It’s a good question, and I believe, a very important one, for a student considering architecture school, and for the profession of architecture in general.

In the Winter of 1993, I moved from Raleigh, NC, to former East Berlin with a group of nine other architecture students to attend the Weißensee Kunsthochschule. It was the pilot year of an architecture exchange program between the NCSU School of Design, where I was attending college, and the Berlin school. It was an exciting time to live in Berlin. The Wall had only come down four years prior. We lived in the former East. Our school was just a 10-minute walk away from our minimalist flat. It was a gritty, raw, and unique social experience.

I mention my time as an exchange student because it drastically shaped my views of the architecture education system. You see, I had been in the NC State University architecture program for three years prior. As with any architecture program I am aware of, the experience was intense. Time-consuming. Focused. You were “all in” in terms of your life, that is, if you “took it seriously.” Some individuals managed their time more effectively than others. Pulling an all-nighter was “normal” and sometimes, from (some) professors I’d had over the years, expected. Almost as if it were a rite of passage into the profession.

The experience was not for everyone. Some dropped out. Certainly more than, say, an engineering curriculum. Perhaps that’s part of “the system” or “process,” and why it has been encouraged for so long. Based on discussions with more senior architects over the years, it’s been going on for decades. Students these days have similar experiences, although some schools offer alternatives. More on that in a bit.

What my time as a student in Berlin offered was exposure to a sense of life balance as an architecture student, something foreign to anything I understood our system had, or at least, at that time in history. What do I mean by “life balance?” Well, for starters, in the Kunsthochschule program, it was expected that students would work part-time in an architecture office while attending school. What? Then, it was unheard of in the US. Where would any student find the time?

It’s unclear if that was a Berlin school “requirement” (I don’t think so because we visited an architecture school in Stuttgart, and the students shared a similar experience), but it was the norm. What this meant was that professors gave students space to fit in working during the day, a few hours a week. Assignments were not as onerous and time-consuming. I noticed that the students took breaks, shared about their work experience, had dinner together, and were rarely “in the studio” after hours. My life as a student was “dialed down,” and frankly, I found it to be one of the most enriching and creative chapters of my eight-year history as an architecture student (I went on to earn my Master of Architecture a few years later through a three-year program at UCLA).

What the experience in Berlin essentially exposed me to was an educational approach that, in my opinion, was simply better. Both the education system and profession were in synch, cross-talking, and aligning on an approach to directing architecture students in a way that was more balanced and “manageable.” Coinciding with some practical, real-life exposure to the day-to-day of our profession and blending it with classic architecture “schooling.” It was both personally enriching and fulfilling.

Because of this, I would change the current US education system to more closely model the one I experienced. As I mentioned earlier, some programs have, in fact, incorporated a working component into the system. But according to research, “(only) 20% of US architecture schools offer some type of professional real-life working experience for a student to intern during the school year within their programs.” I would advocate for architecture school programs to blend professional experience with school, as they are the exception, not the norm.

Awesome – so before we get into the rest of our questions, can you briefly introduce yourself to our readers.

For as long as I can remember, I have been drawn to the visual arts, buildings, and how they are made. At a very young age, I began drawing and sketching, receiving confirmation with scholastic achievement awards in Art throughout High School. I also enjoyed making furniture, which often became gifts for family during a season of life, high school and early college, when time seemed to be a more abundant commodity. I then channeled that love into pursuing a career in architecture. For 33 years, I’ve focused my career on a practice that values excellence in design, craft, and the elevated human experience.

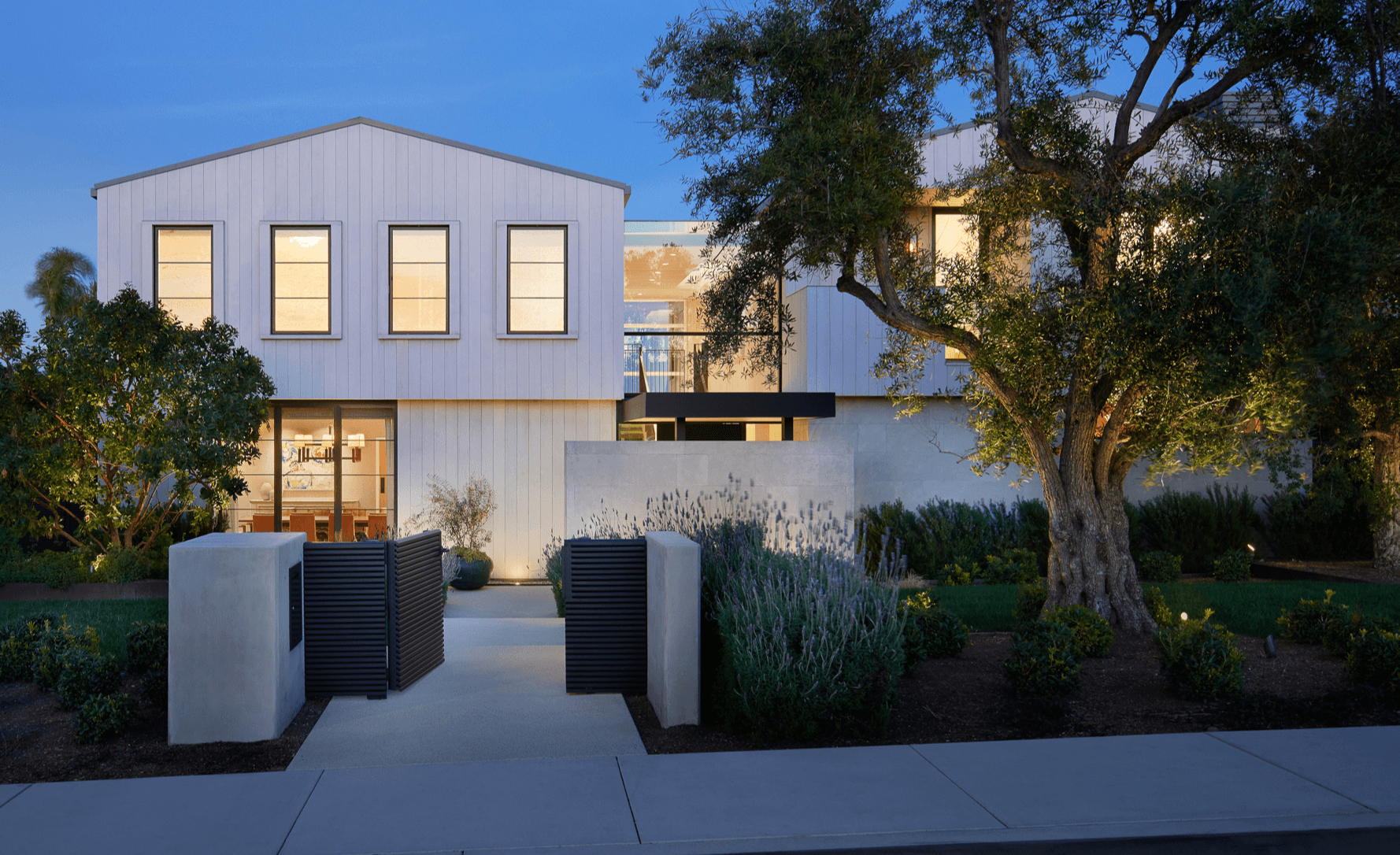

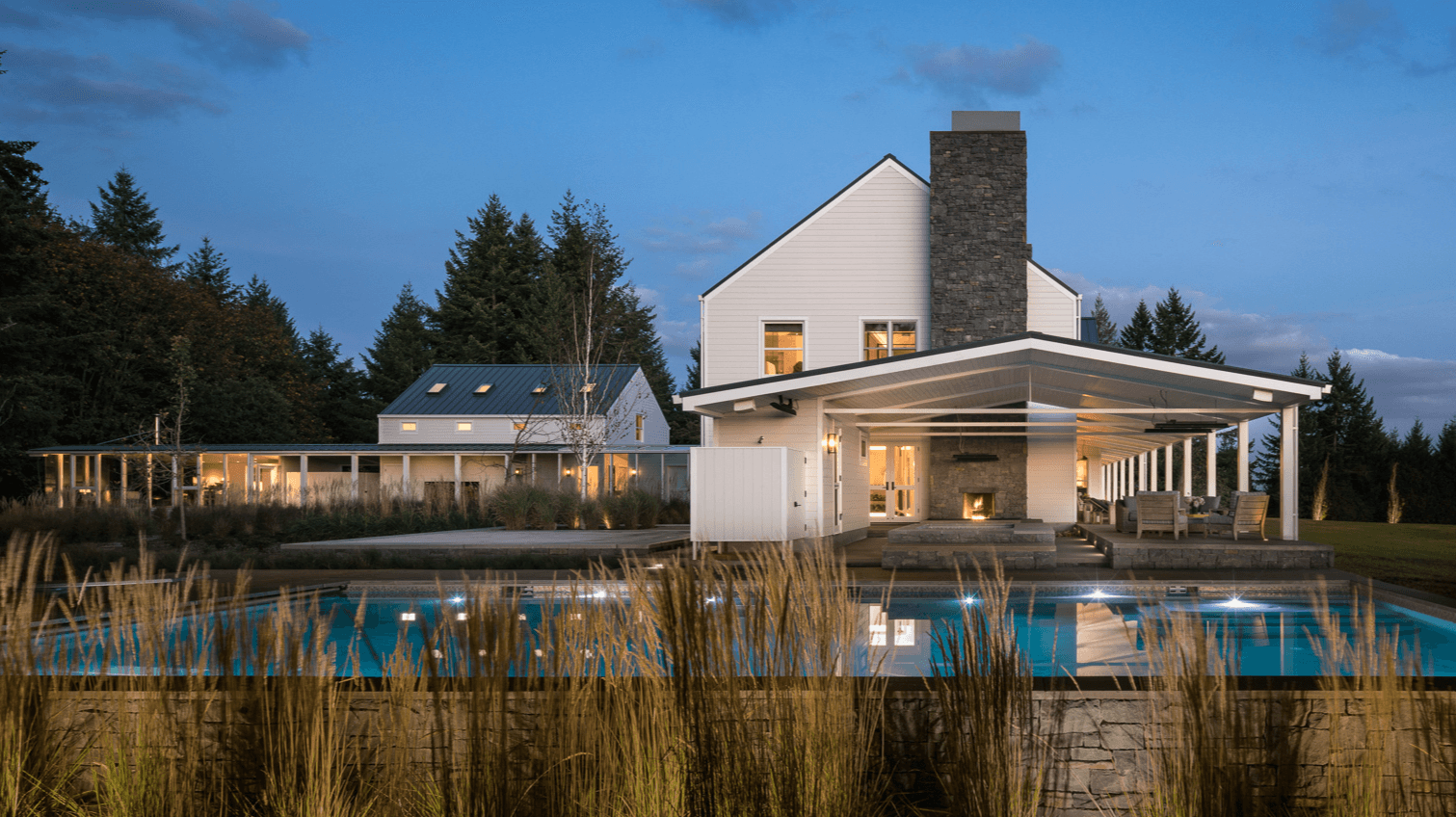

A Modernist at heart, I’ve spent the last 22 years running an architectural business, which has led me to my current role as founding principal of Kempel Architects, a firm based in Santa Monica, California. Our unique purpose rests in its people, uniting the talents and experience of long-time colleagues and fellow architects, Bridget Krajacic and Keith Ireland. Together, we have delivered exceptional homes and estates for discerning private clientele locally and across the country. From the southern coast of California to the wine country of Oregon. North Carolina’s Piedmont to the Gulf Shore of Florida.

As a graduate of the NC State University School of Design and the UCLA Master of Architecture program, I also studied at the Weißensee Kunsthochschule Berlin. This now international program values an interdisciplinary approach, viewing people and art as symbiotic relationships.

Since childhood, I’ve admired the juxtaposition between natural and built environments, which has manifested into the art of drawing, building, and unique visionary skills. I advocate for excellence in craft, understanding to tailor a client’s home fully, and the finest details heighten the experience. Having designed and worked on both small and large commercial projects, including restaurants, offices, and hotels, my greatest passion lies in designing residential spaces. The notion that a well-designed home can positively impact someone’s well-being drives me to consider every last detail. I once spent several days living in a family’s existing home to better understand how sunlight changes throughout the day, all to inform the design of the future dwelling. I believe it matters.

I’ve also dedicated a significant portion of my personal life to giving back to the profession through my affiliations with the AIA, my contributions to the CA professional licensing process, and my service to communities at home and abroad. Whether through the Los Angeles or Durham Chapter of Habitat for Humanity and Downtown’s Union Rescue Mission, or volunteer work in places like Jacmel, Haiti, Caracas, Venezuela, Cairo, Egypt, or in The Shankill of Belfast, Northern Ireland, I’ve experienced how acts of service can enrich the server as much as those being served.

How’d you build such a strong reputation within your market?

What I believe helped build my reputation within my market are a few things:

The first is being a good listener. When clients come to you, they want to be heard. They have ideas. Sometimes those ideas may seem cohesive. Sometimes they’re disjointed.

The second is applying exception design skills. I believe our role as architects is not only to listen, but also to skillfully weave those ideas through the lens of a singular design concept, which then yields a clear architectural solution. How many times have you seen a new home built and it just feels “off” or disjointed, or lacking a visual “harmony,” or when you walk through it, it doesn’t “feel right?” Not us. And that’s because I have always believed that my education at the NCSU School of Design instilled strong Design Fundamentals training, which are essential design skills for tackling any design problem across all disciplines. They, along with raw talent and a strong team, ultimately yield the beautiful work we produce.

The third is being in good relationship. Relationships matter. In my opinion, even more so than the perfect social media blast or Instagram post. They’re all important holistically to a business, but not more than individual people. Having good professional relationships goes a long way and is personally very fulfilling.

For you, what’s the most rewarding aspect of being a creative?

The most rewarding aspect of being an artist or creative is the love for it that is fostered by the process. What I mean by that is, not only is it gratifying to see something you’ve created come to life (and hopefully live a very long life), but to have our clients react to living in our creations, and to see the love they have for living in them. I once had a client say, “I love waking up in this home every day.” Wow. Another said, “This home fosters the life I have always intended.” Huge compliments. And most rewarding.

Contact Info:

- Website: http://www.kempelarchitects.com/

- Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/kempelarchitects/

- Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/people/Kempel-Architects/61566020730274/

- Linkedin: http://www.linkedin.com/in/christopher-kempel-aia-ncarb-9389025

Image Credits

Eric Staudenmaier