Alright – so today we’ve got the honor of introducing you to Chantal Meng. We think you’ll enjoy our conversation, we’ve shared it below.

Chantal, thanks for taking the time to share your stories with us today What’s been the most meaningful project you’ve worked on?

I’ve worked on some meaningful projects so far—although I’m not sure they were meaningful for the world, they certainly were for me. It all started with a small business during my childhood—a popcorn kiosk—followed by my first concert bar, Lavabo, as a teenager. Later, I co-founded the design studio Pol and the gallery space Grand Palais, both in Bern, Switzerland and ultimately earned a PhD from Goldsmiths, University of London. It seems that, from the beginning, I’ve had a mix of entrepreneurial instincts, a drive for collaboration, and a desire for independence. This attitude hasn’t just shaped the projects but has also been important to my overall journey.

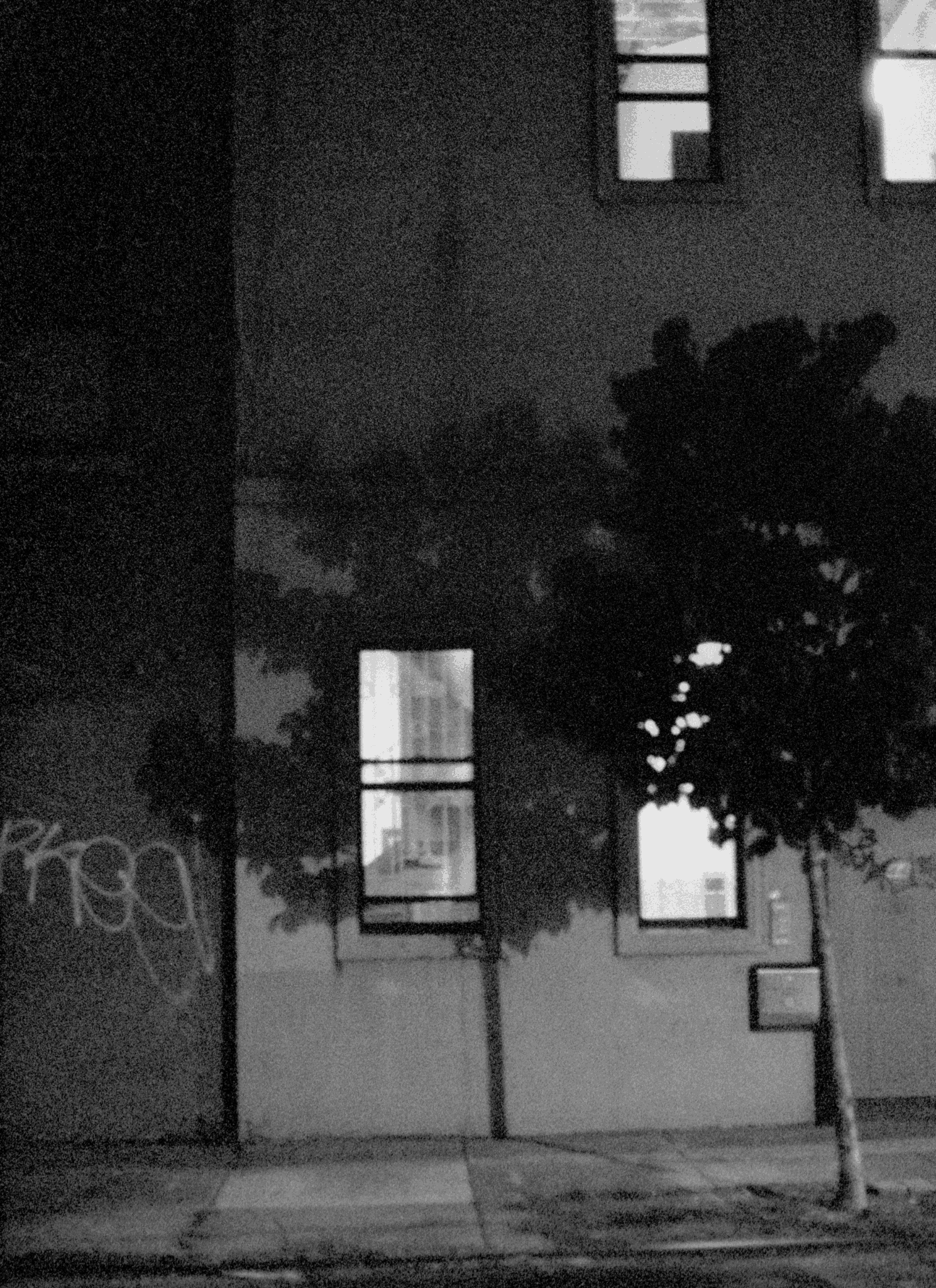

Recently, my biggest passion has been my research on darkness and shadow within the field of environmental humanities. I’m exploring light pollution and the contemporary perception of darkness in urban landscapes. Night studies, artificial illumination, and shadow perception are cutting-edge areas of research, which in my opinion, receive far too little attention—especially when considering their relevance to climate change, social justice, and urban design policy.

I have also dedicated myself to integrating artistic practice into academia as an innovative research method, driven by my strong belief that art and science have neglected collaboration and the exchange of ideas for far too long. I bring this perspective into my teaching. For example, at Parsons, The New School, I teach advanced research seminars on ‘constructed environments’ and ‘visual culture.’ How do images and how does the built environment shape our lives and, by extension, our understanding and ideas? My teaching emphasizes critical and creative methodologies, exploring the complex interactions among historical, cultural, social, material, and economic forces.

I find projects especially meaningful when they arouse people’s curiosity and encourage the next generation to think outside the box, taking agency over their ideas and actions—skills that require consistent practice and reflection.

Chantal, love having you share your insights with us. Before we ask you more questions, maybe you can take a moment to introduce yourself to our readers who might have missed our earlier conversations?

I originally grew up in a very small village in the mountains near Bern, Switzerland. The region nearby, called ‘Ganterisch,’ became Switzerland’s first Dark Sky Park—an initiative aimed at reducing light pollution and conserving dark areas worldwide. I think it’s from this upbringing that my fascination with the night and darkness began.

I first studied graphic design, then worked as an art director and curator. For several years, I co-founded and ran a design studio and gallery in Bern with my best friends. Later, I moved to London to study Sociology at Goldsmiths University, where I completed an MA in Urban Culture and Photography. This eventually led to my PhD and the thesis ‘Light at Night: What is the Matter with Darkness?’ My thesis builds on recent innovations in media ecology research to understand the night as something that is both shaped by technology and is itself a form of medium. Media today needs to be understood in an ecological way—seeing the world as socially constructed and shaped by the meanings we assign to it. Our surroundings and symbolic environment influence how we perceive, understand, feel, and value the world around us.

Today, I’m living in Brooklyn, where I’m an artist, researcher, and educator. I’m a Visiting Assistant Professor at Pratt Institute. I’m the founder of the ‘Night Drawing’ project, which invites participants to sketch the urban night with me, revealing how we fill in what our eyes can’t see. The project examines how we perceive and interpret visual information, challenging the distinctions between reality and representation, especially focusing on what seeing and perceiving the dark means today. Over the years, ‘Night Drawing’ has gained recognition across fields like urban design, visual anthropology, and participatory art.

My art, which deals with the perception and loss of darkness, culminated in the photographic monograph ‘Shadow Typology ‘ (recently acquired by the New York Public Library’s Artists’ Book Collection), the bedtime story ‘Good Night ‘ (soon to be performed as a play), and my first solo exhibition ‘Shades After Dark ‘ in New York. My work has been honored with a Fulbright Scholarship, the prestigious Stuart Hall PhD Fellowship, and the highly acclaimed Doc.Mobility grant from the Swiss National Science Foundation.

I feel incredibly lucky and proud of what I’ve achieved so far. As a first-generation academic and non-native English speaker, it hasn’t been an easy ride I’m excited to keep pursuing what I’m passionate about—contributing to a creative and critical culture, coming up with new ideas, supporting different perspectives, diversity and helping us all stay resilient as we adapt to changing environmental, cultural, and societal needs.

Is there a particular goal or mission driving your creative journey?

The first thing that comes to mind is this: How can we avoid letting social media and AI become the architects of our souls? This feels challenging. It’s not that I’m against modernity or technology—quite the opposite, I find it all fascinating. However, I make a conscious effort to hold myself accountable by staying critical, curious, and attentive. I also try to balance this by working with my hands whenever I can—it helps ground me and keeps things in perspective. That’s a mission I’m committed to pursuing for myself.

Beyond that, if I were to distill my broader mission, it would center around two main goals: building community and integrating analog practices into our increasingly digital lives.

Take my research, for example. It addresses gaps in visual and urban studies and explores shadow concepts in design and art history—work that has both social and environmental implications but is rarely linked or addressed in that way. Drawing at night may seem absurd at first, but it’s precisely in this act that we can rethink how we see—through the process of drawing itself in the dark. Through innovative research, artistic projects, and public engagement, I aim to make contributions that are not only original but also reshape how we see, think, and experience the world around us. At the same time, I try to bring awareness to audiences outside of academia because, honestly, these conversations belong to everyone.

A more personal example? I spent two years living nomadically on a boat in London, moving the boat every two weeks to a new neighborhood to avoid mooring fees—a lifestyle that’s becoming common as people navigate London’s real estate crisis. Living off the grid taught me a lot about community, friendship, and sustainability. For one, I became hyper-aware of my own consumption—how much waste I produced, how much energy I used, and the difference between waking up to 4° or 8° on a winter morning. It’s a humbling experience when you see those things firsthand.

I think experiences like these put things into perspective. It reminds me how small we are in the grand scheme of the universe. Maybe we’d all benefit from not taking ourselves quite so seriously. This hyper-individualistic mindset—where everything hinges on ‘me, myself, and I’—might not be the most sustainable way forward.

In your view, what can society to do to best support artists, creatives and a thriving creative ecosystem?

One way I see to make this happen is to start early and raise awareness that we all need the arts in our lives. Think about it—we need drawings and bedtime stories just as much as we need movies, music, or great architecture. All of these things contribute to the structure of our environment, shaping not just human lives but also those of non-humans. So how do we get there? I think it starts with a fundamental rethinking of education, and this process should kick off before kindergarten. The Scandinavians are a great role model for me in this, as they integrate things like empathy lessons into the early curriculum. Empathy is key to building close relationships, preventing bullying, and fostering collaboration in the workplace. It’s essential for developing leaders, entrepreneurs, and managers—people who will later have a say in shaping decisions.

I’m currently working on the second edition of my bedtime story ‘Good Night,’ which will eventually transform into a theater play. The story follows an urban fox’s journey and explores the relationship between darkness and humanity. Through imaginative storytelling—such as giving darkness and the fox their own voices—I invite the audience to engage with the night and reflect on the idea that we are not the ultimate subjects of this planet. As Elisabeth Bronfen puts it in her wonderful book ‘Night Passages,’ we need the night to undo the day, and this is an important state of transition, as well as for imagination. Jonathan Crary adds a great perspective in his book ’24/7: Late Capitalism and the Ends of Sleep,’ where he explains how sleep aims to be controlled by capitalism and the push for efficiency—but not quite fully yet. It’s one of my favorite books, by the way.

Let me add another example that supports creativity and, ideally, sustainability. As I mentioned, it’s about building community and creating more spaces for discourse, dialogue, and encounters in public spaces. When I co-ran and co-curated the art space Grand Palais in Bern, Switzerland, we faced a challenge: how to keep the space open during the summer when we couldn’t afford staff and foot traffic was low. Instead of closing, we collaborated with the amazing artist duo Lang/Baumann, who came up with the idea to transform the entire building into a sculpture called ‘Open.’ They connected all the building’s doors and windows, creating tunnel-like passages that essentially turned the structure inside out. The result was a ‘perforated’ building that anyone could walk through or look into at any time. In doing so, they beautifully redefined accessibility and interaction with art.

So, a thriving creative ecosystem needs all these things: interconnected networks, critical reflections, imagination, exchange, institutions, education, innovation, and, of course, funding. But above all, it requires communication, fostering experimentation, and bringing people together. It’s in these moments of connection and creativity that we can truly reimagine the world we live in.

Contact Info:

- Website: https://www.urbandarkness.net/

- Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/chantalmeng/

- Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/nightdrawing

- Linkedin: https://www.linkedin.com/in/chantal-meng/

- Other: https://www.nightdrawing.com/

Image Credits

1. Chantal Meng — Photo © by Brandon Perdomo

2. Night Drawing Event, New York — Photo © by Brandon Perdomo

3. Chantal Meng — Photo © by Chantal Meng

4. Publication ‘Good Night’ by Chantal Meng

5. From the series ‘Shadow Typology’ — Photo © by Chantal Meng

6. From the series ‘Shadow Typology’ — Photo © by Chantal Meng

7. ‘Open’ by Lang/Baumann, Grand Palais Bern — Photo © by L/B

8. Regent’s Canal, London — Photo © by Chantal Meng

9. Night Drawing Event, London — Photo © by Lucy Parakhina