We recently connected with Byrne Owens and have shared our conversation below.

Byrne, thanks for taking the time to share your stories with us today It’s always helpful to hear about times when someone’s had to take a risk – how did they think through the decision, why did they take the risk, and what ended up happening. We’d love to hear about a risk you’ve taken.

I work a remote job in tech, not a creative role by any means, but it pays decently. It just isn’t my passion. My wife is an architect. A year ago, she left a corporate firm in LA so she could finish her licensing exams and pursue residential architecture. We’ve been staying at her parents’ in Monterey while she wraps up the testing to save money. All this to say, when she finishes her tests, we’ll make a decision on where to move.

While living here in Monterey, I shared a pilot script I wrote with a working writer friend in LA in hopes of receiving some hard-hitting feedback. He liked the script so much that he forwarded it to his manager. I’m now signed with Heroes & Villains and waiting to meet with producers about either pitching my script or joining a team in some capacity. I really have no idea how this will pan out, but both my wife and I agreed that entertainment is where I’m meant to be. Mind you, I’m not about to quit my tech job without solid prospects, but the fork in the road is fast approaching, and there are some serious factors to consider.

As we know, LA is incredibly expensive. And this past year for entertainment has been rough for working professionals, to say the least. Many people have walked away from the industry because of how slow the work has been, especially for those located in LA. The safe bet would be to stay in tech and not pursue entertainment. But what is “safe” anymore? All of corporate America is going through an identity crisis, and with such terrible inflation, there are no assurances. Certainly, it would be ideal to stay in Monterey, where we’re close to family. But even so, the move to LA isn’t the real risk. Plenty of writers and entertainers live outside of LA and make it work. The real risk is in devoting creative time at the end of the day to pursue my passion, with no real guarantee that the use of said time will lead to anything other than the joy of the process. This is a wonderful philosophy, but when you’re 41 and still hope to one day be in (notice I don’t dare say own) a house, have kids, and live a comfortable life, time is of incredible value.

My wife and I believe I have what it takes to thrive as a creative. I’ve been writing, directing, performing, and outright producing my own films since college, and telling stories is when I feel the most alive. In a world where the penalty for not being good enough is severe, taking risks and gambling financial success on a fickle and subjective art is no joke. This is me (and those who love and support me) choosing to take that leap, and knowing that whatever happens, I was true to myself and what I believe in.

Great, appreciate you sharing that with us. Before we ask you to share more of your insights, can you take a moment to introduce yourself and how you got to where you are today to our readers.

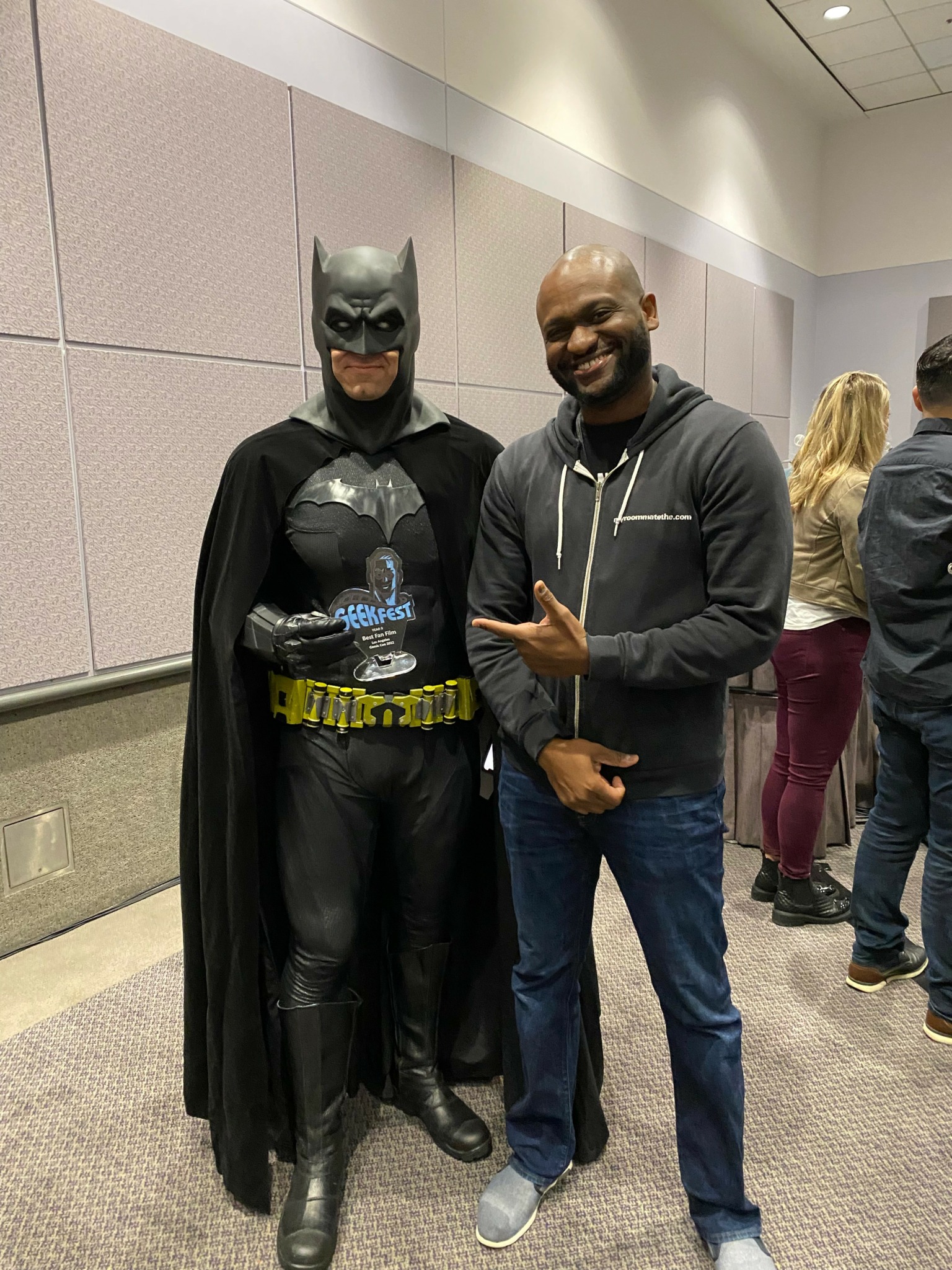

I’m an only child, raised in Southern California. For as long as I can remember, I always gravitated toward fantastical fiction, namely cinema. I would watch movies like Star Wars, Batman, Ghostbusters, Aliens, and anything with an action-packed adventure, and then go out into my backyard and play out my own fan fiction in costume. I would have friends over, and we would either cosplay and pretend to be our favorite heroes, or we would stage action figures as if we were making our own movies. It wouldn’t be until college that I started performing, writing, and directing plays. It was then that I knew my calling was in creative production.

From then on, I would produce short films on small budgets with actor friends in LA. We posted them on YouTube and would get great responses from audiences. With my best friend from college, Lu Louis, we co-produced a series of films called My Roommate the…? It centered around one man who experienced living with a different roommate in every stand-alone episode. It was my master’s program in filmmaking. I worked odd jobs to pay rent, living check-to-check just to keep myself afloat while we made magic.

I was a producer in the broadest way you could define the role. I took on every position that I couldn’t afford to pay others to do. I would write the scripts, run casting calls, pre-produce the shoots, hunt down locations, props, and costumes, draw out storyboards for our crew, rent the lighting and camera equipment, direct the actors and crew, perform major or minor characters, order craft services, edit the footage, arrange sound effects, and then market the project with promotional posters, merch, and social media content before ultimately posting the finished film to YouTube. Rinse and repeat for 12 years and 65 episodes and change.

Our series was SAG-eligible, so we would use the eligibility vouchers as a way of paying actors to perform. It didn’t hurt that they also enjoyed and believed in our scripts and style.

At one point, we were financed by a production company and produced a whole season as paid artists. I had the incredible experience of writing for and directing Issa Rae in My Roommate the Awkward Black Girl, and had the opportunity to use real sets and high-quality equipment at the YouTube Space in Playa Del Rey. The production company later went bankrupt due to some shady dealings with other creators, and we narrowly avoided getting bamboozled ourselves. We decided to launch a Kickstarter in hopes that our 60k subscribers would help fund more episodes, but like many crowdfunding attempts in entertainment, we felt short of our goal.

I took on a 9-5 tech job to pay off credit card debt, but eventually decided to jump back in for one last ride in the self-funded producer world with our biggest project to date: My Roommate the Jedi. It went on to win 11 festival awards across all categories. This film took me nearly five years to complete because I was juggling the rigorous production and editing schedules with my daily 9-5. If you want to understand the kind of filmmaker I am, this is the one to watch and chat about. Every aspect was a challenge, and there were several times when any sane person would have quit. The costumes, the props, the action sequences—it was bigger than anyone should attempt without a legitimate production backing. Part of the reason I chose to do a fan film was because I wanted a concept that was universally known to audiences, so I could lean in on a story that would normally require a suspension of disbelief. The average viewer tends to disregard unfamiliar high concepts in today’s oversaturated indie film market. I stand by the decision to go the fan film route in spite of it being taboo in the elite film community.

Today, I’m screenwriting and saving my chips. I’ve come to understand that I did my time as a self-funded artist. My work speaks for itself, and now we’ll see what productions my ideas and scripts can attract on their own. I recently signed with Heroes and Villains, and I look forward to whatever projects materialize from my scripts and meetings. If the opportunity arises to produce the way I did with “My Roommate the…?” but with sustainable budgets and resources, I wouldn’t hesitate to jump back in. Till then, we’ll see where my scripts take me!

Can you share a story from your journey that illustrates your resilience?

Getting “My Roommate the Jedi” into the can was its own insane journey that challenged my fortitude as a filmmaker, but what really tested my commitment to completion was the editing process. When we started production initially, we had two incredibly talented VFX artists signed on to animate our spaceships and laser/lightsaber action sequences. At that time, I really had no idea how to animate or edit advanced effects like that. I couldn’t afford to pay the VFX artists either. They were pros who typically worked on major productions, but they loved the concept so much that they offered to do the work for free, as long as it was on their time and we didn’t rush the process.

About six months after we completed filming, and with a quarter of the animations complete, both VFX artists had to drop out to take on bigger projects that required their undivided attention. Bringing on other VFX artists was a challenge too since each artist has their own style and hadn’t been involved in the earlier planning of the shots and direction. My choices were A) Quit or B) Do it myself. In the past, I always picked option B. It’s because of option B that I know as much as I do. It’s actually how I learned to edit. But this time it was different. Animating? I’m good with hand-drawn illustrations, but this was next level. We had gone through so much turmoil to finish filming this project, quitting just wasn’t an option. So I went with option B.

With the help and mentoring of some industry friends, and the school of YouTube, I learned After Effects. I did all the lightsabers and the lasers. I paid an editor in Pakistan to help me with rotoscoping each frame as I added spaceship interiors and effects behind the actors. I learned how to animate ships, objects, smoke, light—you name it. I was lucky to have help from one of the original animators to do a short AT-ST walker sequence (super advanced stuff), but it was mostly me working late nights after work for four years straight. It felt like I was digging out of a jail cell with a spoon.

Looking back, had I known what would have transpired, I don’t know that I would have shot the film at all. My eyes were bigger than my stomach then. But what if that’s the only way to get something done the way we envision? Maybe that time with “My Roommate the Jedi” will be the only time I get to produce exactly what I envisioned in my head— for better or worse. But I truly believe the ultimate finished product is a testament to commitment and belief in a dream. I don’t intend on taking 4-5 years to single-handedly edit another film, but I will always remember the feeling of choosing patience, hard work, and sacrifice to see something through the right way. I believe that kind of grit is what sets artists apart.

Is there something you think non-creatives will struggle to understand about your journey as a creative?

I think it’s important to preface that when we use the term “creative” in this context, we’re referring to those whose tasks specifically demand a unique and artistic approach that begins with an empty space and evolves into a deliverable piece of entertaining and/or useful product. This sentiment has, and continues to, evoke debate among artists and industry professionals since there are so many necessary roles that orbit an expressive production. I would argue there is creativity to be derived from all of these roles, even if on the surface, they don’t represent artistic creativity in the way a writer, performer, painter, or craftsman would.

What I think gets lost in the creative vs. non-creative understanding is the notion of value. Those who purposely choose not to engage in artistic careers tend to weigh creative value against some measure of envy. A sentiment like: “Must be nice to just make art all day, while some of us have to work real jobs that require the grind of copy-pasting formatted spreadsheets and answering to stakeholders and market demands.” The struggling artist may envy the financial rewards of being a “bean-counter”, but they hardly long for the duties that earn those rewards. If anything, it’s often the creative’s aversion to that spreadsheet world that drove them to pursue an artistic path in the first place.

But it’s not so much the other way around. Everyone longs for creative expression in some capacity. It’s the most visceral form of freedom to have a sense of taste and be able to express it to a responsive audience. Creative expression isn’t a privilege but a right to all individuals. However, when money gets involved, suddenly one’s ability to create quality work and make it look easy gets slapped with the law of diminishing returns.

Example: A talented artist may complete something in 1 hour, whereas it would take an inexperienced artist 5 hours to complete the same project. But the non-creative world so desperately wants to assign equal value to both artists, and then asks the more talented artist to do more with the remaining hours of the day. What about the years of sacrificing a steady income, struggling to stay afloat, practicing repeatedly, experimenting, and failing that brought the talented artist to this point? Was that worth nothing? What about the audience’s demand for more from the more talented artist over the inexperienced artist?

There’s a denial of the cost of quality and compensation that non-creatives tend to leave off their spreadsheets when applying value to creative delivery. I don’t know that this tug-of-war will ever really go away, but if we can make the conversation easier to have between the left-brainers and right-brainers, we may find that it’s mutually beneficial to appreciate the difficulty of the creative process when it isn’t obvious in the general process.

Contact Info:

- Website: https://myroommatethe.com

- Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/byrne_owens/

- Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/byrneowens

- Linkedin: https://www.linkedin.com/in/byrne-owens-iv/

- Twitter: https://x.com/ByrneOwens

- Youtube: https://www.youtube.com/c/myroommatethe

- Soundcloud: https://soundcloud.com/discoverfilm/316-byrne-owens-my-roommate-the-jedi

Image Credits

Image 1: Randy Koszela, Myself, Matthew Hibbs, Lu Louis

Image 2: Myself, Lu Louis

Image 3: Chloe Carabasi, Matthew Hibbs

Image 4: Lu Louis, Myself, Lamorae Octavia, Issa Rae, Catfish Jean

Image 5: Tristen Macdonald Gerdes, David Neyts, Juan Teed Lopez, Lu Louis, Myself, Chad Jamian Williams, Chris Mollica, Catfish Jean, Alexandria Skaltsounis