We recently connected with Brubey Hu and have shared our conversation below.

Brubey, looking forward to hearing all of your stories today. Can you talk to us about a project that’s meant a lot to you?

During my graduate studies at the University of Waterloo, I created a self-authored artist’s book named Returning, Dreaming & Talking (回与梦呓 in original Chinese). This set of books consists of a collection of texts exploring the themes of home and identity, a sense of drifting, continuously, from place to place, and as a female raised in both China and Canada. I first wrote the poems in Chinese. With the assistance of a professional translator converting the texts into English, I then invited my Chinese family and friends to collaborate on translating these poems a third time from English to Chinese. Through this repeated process, I am interested in examining how much information, meaning, and emotion evaporated between the three versions.

I chose the literal form of poetry because there is more room for freedom and ambiguity. Many of my original poems utilize ‘dream’ as the agency to retrieve memories and connect with my past; however, dreams and memories are personal and inherently untranslatable. The compelling result of the third translation from English to Chinese demonstrates that the literal languages, in this case, become dualistic instruments of precision and ambiguity. On one hand, the precision of translation is delivered by translators’ knowledge of both languages, as well as the combination of words and grammar which are essential terms of languages. On the other hand, the ambiguity is generated contextually from one line to another, from one paragraph to another, facilitating an open-ended conversation between the poetry and the translator.

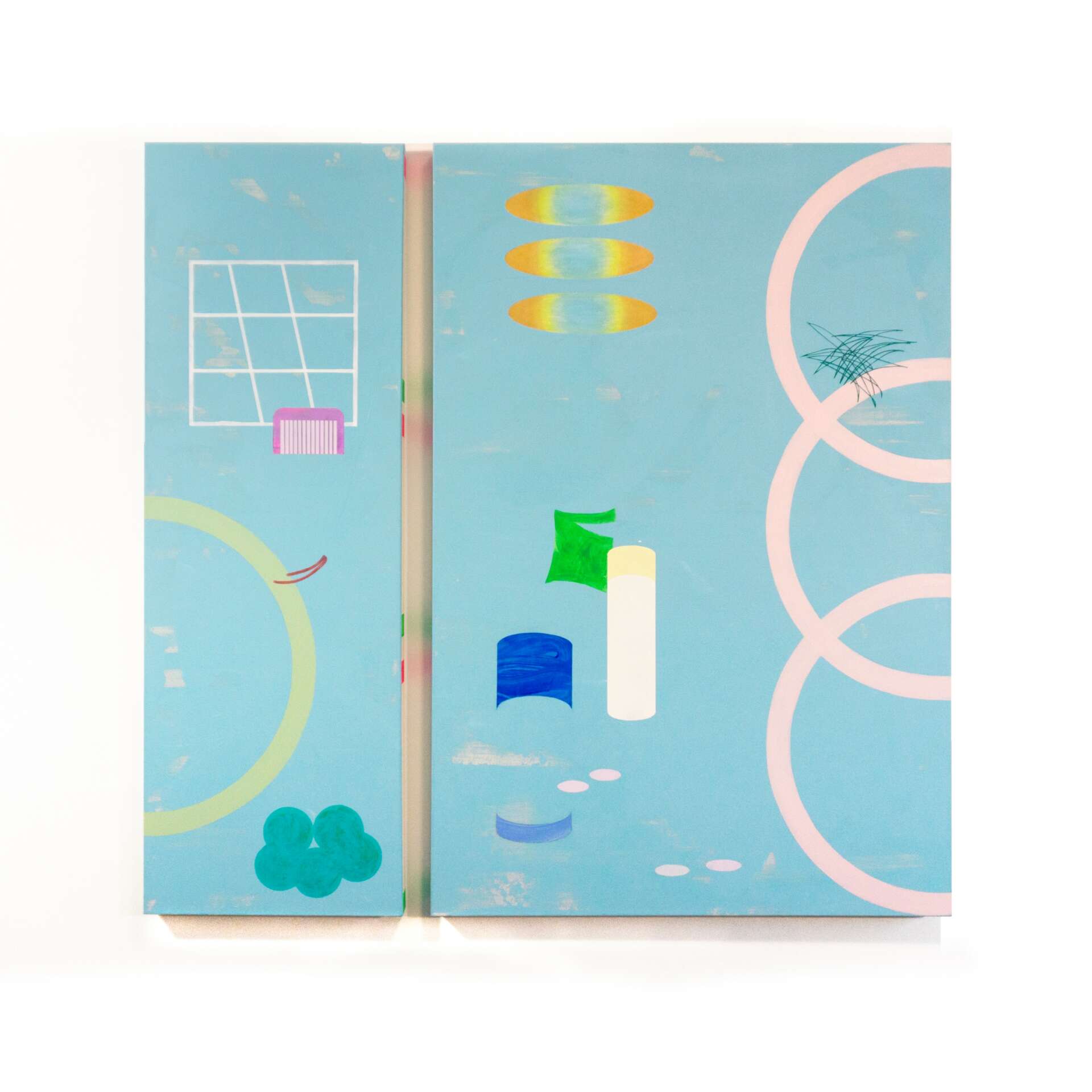

The use of blue grids was inspired by graph paper—a common tool for mathematics and laboratories. In this book, some of the graphs occupy a whole page while others are divided into sections correlating with the texts. Incorporating grids as the underlying rule, I also investigate the rhombus shape as a distortion of the square, which is another nod to translation, to the angled reflections that occur from windows as light streams into an interior space. To me, it is an equally subtle way of marking my identity and authorship as female, as the rhombus shape formally refers to the female genitalia. Both of the above notions suggest logic as well as rationality, and even coldness without any emotions; however, the narrative is built by the way the rhombus shapes coordinate with the grids as well as transfigure the content of texts into visual geometric forms.

The binding method for this set of books is singer-sewn binding, which utilizes a sewing machine to stitch the pages and the cover together. Due to its durability and ability to open flat, this binding method is widely employed for passports and thin notebooks which are designed for travelling purposes. The poems are indicated with dates, referring to the format of diary/journal. They record my journey of constant moving and travelling, reflections of my hybrid identity, and retrospections of the past.

As always, we appreciate you sharing your insights and we’ve got a few more questions for you, but before we get to all of that can you take a minute to introduce yourself and give our readers some of your back background and context?

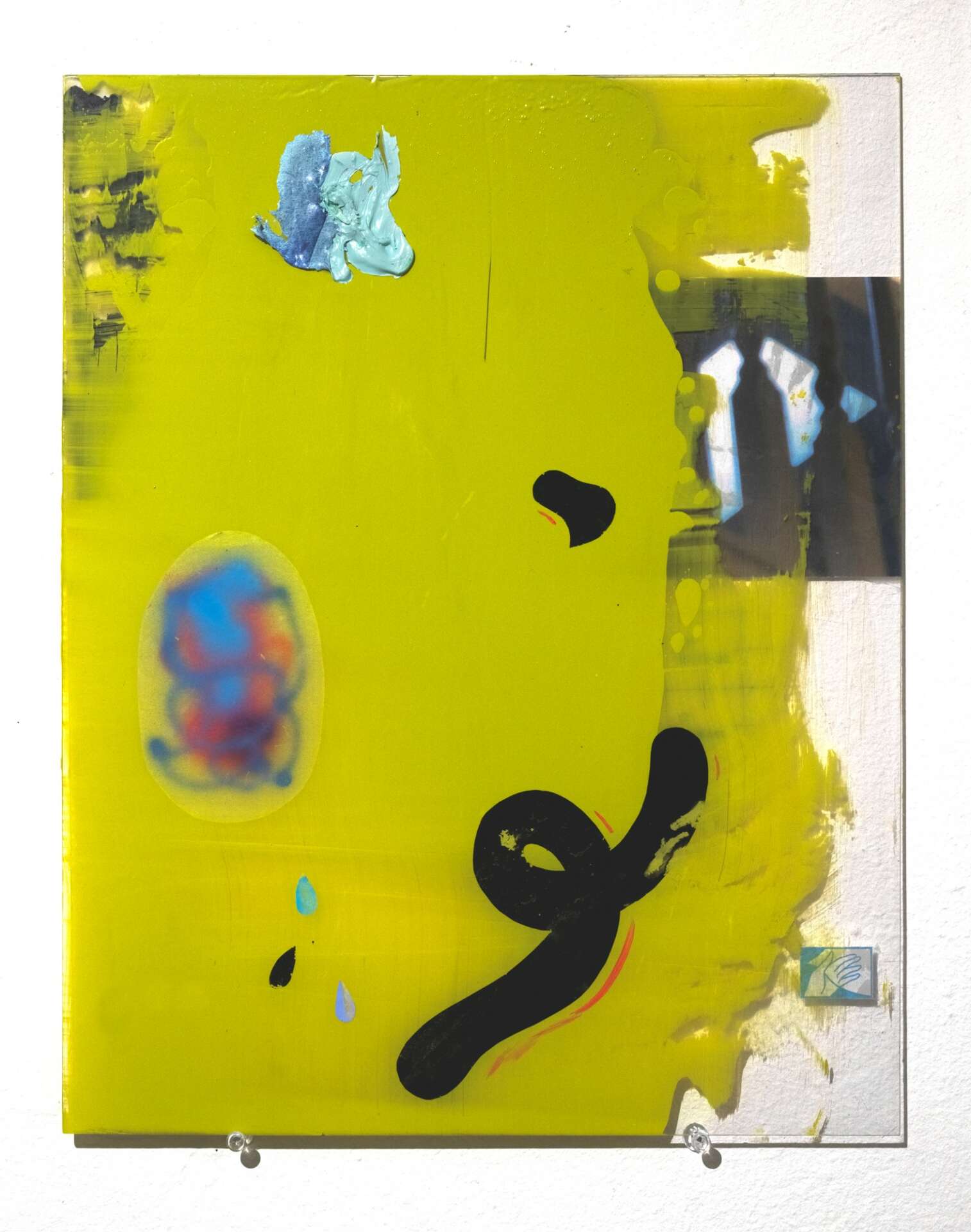

My name is Brubey (Wanzhi) Hu, and I am a Chinese artist, designer, and educator currently based in Toronto, Canada. I hold MFA from the University of Waterloo and BFA from the Maryland Institute College of Art. In my practice, I explore the mundane, architectural space, translation, memory, and colour theory through poetics and transcultural feminist perspective. With subtraction, the works are transcribed responses to my surroundings, metaphors of consensus and social subjugation, and they examine the unspeakable poetics and emotions evoked in the process of creating. The paintings distill physical sites and objects into the two-dimensional plane while embedding memory and familial kinship into abstract visual compositions that resonate distinctively with each viewer based on their experience. Oscillating between premeditation and improvisation, I compose and deconstruct the space and objects around me, to depict the nuanced visual poetics from the residues of the everyday.

My work has been exhibited nationally at Art Mur in Montreal; Winchester Galleries in Victoria; Art Museum at U of T, Red Head Gallery, University of Waterloo Art Gallery, Cambridge Galleries, and Art Gallery of Mississauga all in Ontario. I have also participated in numerous artist residencies, including BAiR Emerging at Banff Centre for the Arts and Creativity in Canada, and Painting & Mixed Media Residency at the School of Visual Arts in New York City, US. My practice is supported by Canada Council for the Arts and Ontario Arts Council.

Originally born in Xiamen, China in 1994, I moved to Vancouver, Canada for high school, and then to the US for undergrad. I have worked as a sessional lecturer at the University of Toronto Scarborough and the University of Waterloo. Besides teaching, I also work as a freelance graphic designer for numerous clients. Currently, I sit on board of CAFKA (Contemporary Art in the Public Space) in Waterloo Region, and am the co-director at Tangent Collective.

What’s a lesson you had to unlearn and what’s the backstory?

I grew up in an environment that has long been ruled under the patriarchal configuration. Growing up, I unconsciously learned and internalized misogyny so deeply that I didn’t realize how harmful it was until I no longer stayed in that environment. In her book Misogyny, Japanese sociologist Chizuko Ueno points out that “Misogyny is an illness that not only men have it, but women are also infected”. Misogyny permeates every aspect such as culture, language, daily life, etc, and has profoundly affected my psyche and my relationship with other women. I have to make an intentional effort to unlearn misogyny through reading and contemplating feminist theories, observing closely why I behave and think in certain ways, and being allies to people who also suffer from the patriarchal system. It hasn’t been exactly a pleasant journey. There were many times I felt angry and hopeless—witnessing and hearing about systematic and physical violence and oppression imposed on females. I try to turn the anger into fuel to conduct research and find ways in my creation to counter the patriarchal structure.

My recent research investigates the convoluted relationship between womanhood and domestic space. Domestic space has been widely recognized as a feminine arena influenced by conventional heteronormative configuration. Femininity has been feudally linked to the domestic realm including unpaid housework, caregiving, and personal (be)longings. Countless females are taught to look after their domestic surroundings growing up while the patriarchal system continuously devalues the significance and indispensability of housework. My next step is to turn this research into a series of paintings, sculptures, installations and an artist’s book. Experimenting with both discards and common household items, I intend to confront the intensive labour behind a well-kept home, as well as to evoke the poetics and beauty by subverting the embedded misogynist narratives.

Can you tell us about a time you’ve had to pivot?

I lived in Xiamen, China until the age of 16 when my parents decided to emigrate to Vancouver, Canada. It was difficult to say goodbye to all the friends and family, and to the place and life that I was so familiar with. We moved frequently during the first two years as we settled in. I also moved once a year when I relocated to Baltimore for undergraduate studies. Upon graduation, I decided to pursue my master’s degree and moved to Ontario where I currently resides. By nature, I am not a person who is fond of relocating because moving is exhausting and requires so much physical and mental labour. I couldn’t help but wonder what home actually meant to me. I fell into an identity crisis for a while and felt I belonged nowhere—I am Chinese, but I live in Canada, and each year I grow more apart from my Chinese friends who still live in China. These friends no longer consider me as fully Chinese, and I can never be a full Canadian no matter how long I have lived and will live here. Luckily my job as an artist allows me to transform the disgruntlement and imbue this kind of hybridity of identity into my artwork.

It took me a total of 8 years to finally feel at ease expressing myself and conversing with others in English. My works often reflect the aphasic state that transnational immigrants endure while being accustomed to an unfamiliar cultural landscape. The state of aphasia does not only engender the frustration of illegibility or a lack of means for expression, but it also prompts extensive sensibility of one’s material and spiritual surroundings. By composing basic shapes, many of my artworks appear to be formally minimalistic; they appear at first to lack a message. When there is not enough information, ambiguity occurs, a notion that allows more blank room for viewers from different backgrounds. The titling of the works becomes a window of opportunity for the viewers to speculate the narratives of the work and to insert their realities and imaginations. The freedom to establish mutual consensus exemplifies and promotes the reciprocity of multicultural encounters. Till today, I appreciate the barriers I bumped into and all the mistakes I have made which both make me more open-minded and placid about any ups and downs.

Contact Info:

- Website: brubeyhu.art

- Instagram: @brubeyhu

Image Credits

Personal photo credit: Yantong Li Exhibition photos credit: Toni Hafkenscheid