Alright – so today we’ve got the honor of introducing you to Brie Hines. We think you’ll enjoy our conversation, we’ve shared it below.

Alright, Brie thanks for taking the time to share your stories and insights with us today. Can you tell us about a time that your work has been misunderstood? Why do you think it happened and did any interesting insights emerge from the experience?

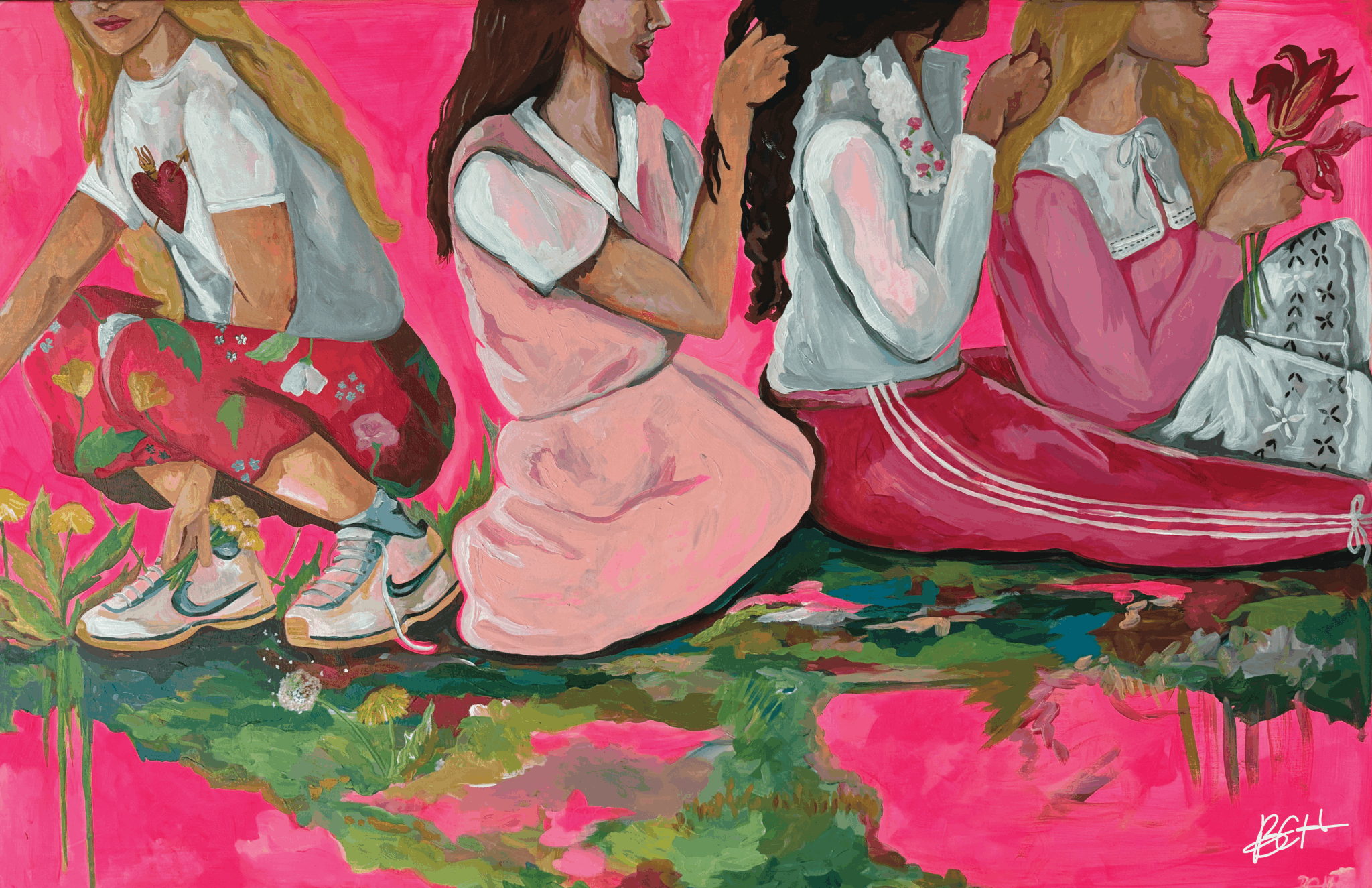

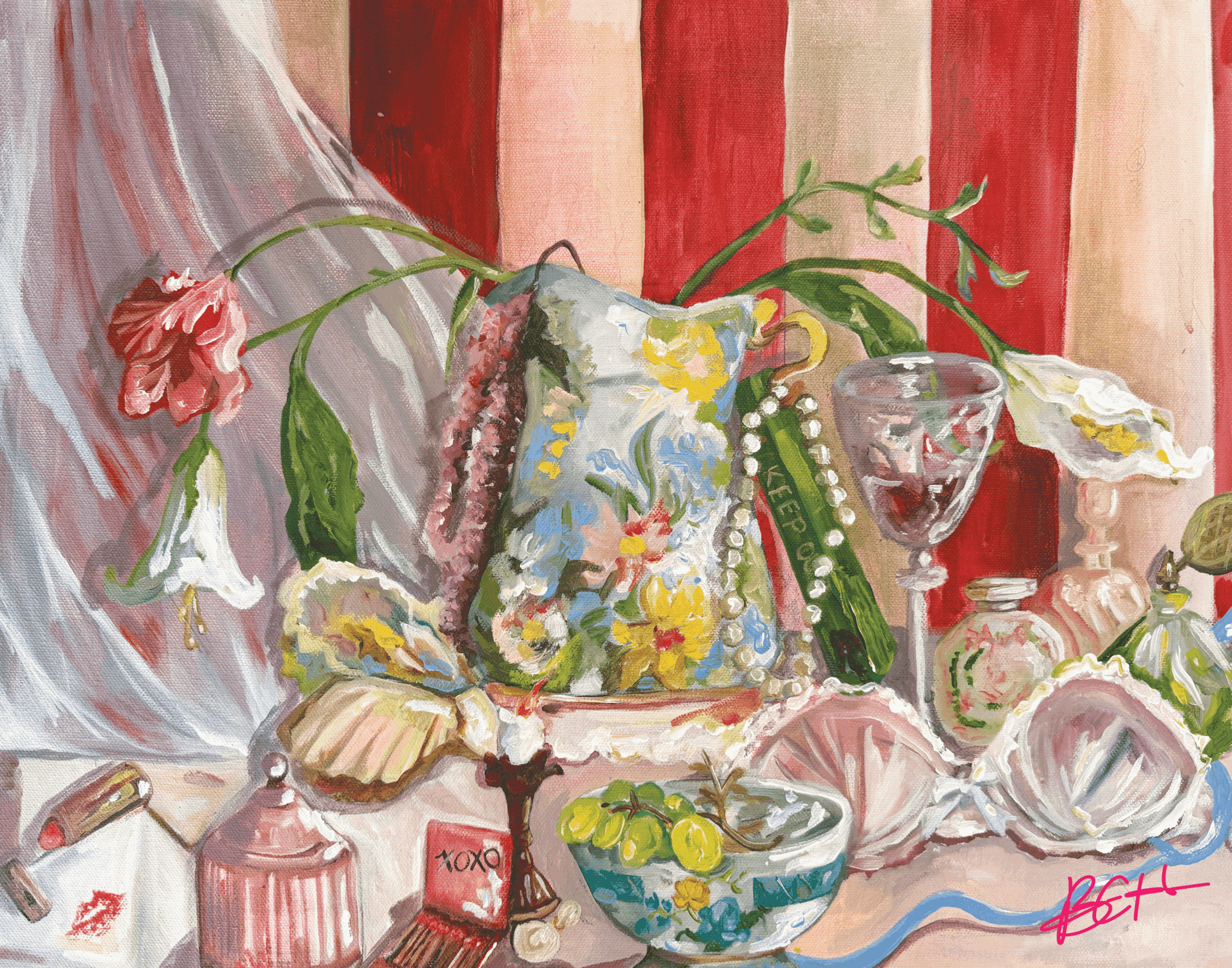

I create hyper-feminine art. Mischaracterization is an understatement, but it’s also part of the reason I paint. When I hear reactions like, “That’s cute,” it mirrors the patronizing way so many women and feminine people are perceived just for existing. My work leans into the stereotypes of femininity—pinks, boldness, motifs of fashion and girlhood—because I want to reflect what it feels like to be seen as a woman. These elements are often dismissed in the art world, and why? Because they reflect the experiences of women?

Throughout my life, I’ve felt conflicted with embracing my own femininity. I grew up balancing two worlds: ballet and competitive swimming. In ballet, there was constant judgment, and I was teased for the frilliness, the tutus, the hyper-feminine aesthetic. Swimming was different. As an accomplished D1 collegiate athlete, I learned that I was only truly seen, heard, and taken seriously when I adopted a more masculine attitude—I yelled, I cursed, I pounded my chest. At the time, it felt useful. Looking back, I see a missed opportunity, just as I regret ever feeling ashamed of my years as a ballerina.

Ballerinas are unbelievably strong—just as disciplined and tough as any athlete. The presence of tutus and pink doesn’t take that away. My femininity doesn’t make me small; it only feels that way because the world perceives it as such. There is power in femininity, and my art exists to reclaim it.

As always, we appreciate you sharing your insights and we’ve got a few more questions for you, but before we get to all of that can you take a minute to introduce yourself and give our readers some of your back background and context?

I’ve always been someone who feels deeply. As I got older, understanding and managing those emotions became more complex. Art, in all its forms, has always been my way of processing and communicating things that are difficult to put into words. I think this is something many storytellers and artists can relate to.

My creative path has never been linear—I’ve dabbled in many disciplines, with a background in marketing, photography, and graphic design. But no matter where I was in my career, I always found myself reaching for a paintbrush.

When I first started committing to my craft, I created abstract work—pieces born purely from emotion. I painted with my hands, letting color guide me in what felt like an interpretive dance. While I loved that era, I now realize I wasn’t confident enough to tell stories more directly. That changed after my first trip to Italy.

Everywhere I looked, I saw imagery of Medusa—but always as a villain. It struck me how often her story, like so many women’s stories, had been told and retold by men. I sketched a quick idea while I was there, and as soon as I returned home, I painted her as I saw her: a victim. That piece became a turning point. It gave me the confidence to lean fully into storytelling, and I’ve been exploring women’s narratives ever since.

My work is rooted in feminine storytelling, and I draw a lot of inspiration from fashion—not just as a motif in my paintings, but as a medium itself. I love incorporating my art into fashion through high-quality scarves and one-of-a-kind hand-painted clothing, allowing my work to exist beyond the canvas.

Ultimately, I want my art to challenge perceptions of femininity, reframe stories that have been misrepresented, and create pieces that make people feel seen.

Can you tell us about a time you’ve had to pivot?

I’ve learned that being an artist takes time—time to be recognized, time to be chosen. I’ve also learned that waiting for opportunities isn’t sustainable, especially when art is your desired career. After facing rejection from countless galleries, I decided to pivot. Instead of waiting for a ‘yes,’ I started creating my own opportunities. I curated my own shows, crafting immersive experiences that not only showcased my work but also aligned with the stories I wanted to tell. Just as importantly, I was able to support other creatives in my community.

Two years ago, I put on a show featuring my Medusa series. I partnered with a local brandy distillery, designing themed cocktails and transforming their back space into a gallery. We draped fabrics, set backdrops, and turned the night into a fully realized experience. I was able to hire a friend to read tarot, another to perform original music, a photographer to take personal portraits, and a designer to create a custom costume for me. It was a night that blended multiple art forms into one cohesive vision.

That experience deepened my understanding of how art can be collaborative. More recently, I’ve explored the intersection of visual art and culinary arts by painting live at intimate dinner parties. Working alongside chefs to design table settings and menus has allowed me to bring my work to life in new ways, proving that art isn’t confined to galleries—it’s an experience, a conversation, and more beautifully, a gathering. I often wonder when my art feels the most important to me and it’s usually the conversations I am able to have, the people I am able to meet and I have been surprised but so gracious at the community it has given me.

How can we best help foster a strong, supportive environment for artists and creatives?

Art is something so deeply ingrained in creatives that asking an artist not to make art is like asking someone not to sneeze—or asking my beagle not to bark. Sharing that art, however, is another story. It’s exposing a part of yourself that most people would only reveal in a therapist’s office. And yet, putting it out into the world opens it up to judgment, misinterpretation, or, worst of all, indifference. Love it or hate it, art is meant to make you feel something. And at the end of the day, it is easier to be criticized than dismissed entirely.

Beyond its emotional and cultural significance, art is an undeniable economic force. The ideas and aesthetics created by artists—both small and widely recognized—shape industries, trends, and even corporate decision-making. Yet, artists are rarely given the recognition or financial support that matches their influence. Society needs to do more than just appreciate art; it needs to invest in artists. This means creating more opportunities for collaboration, ensuring that the creatives behind groundbreaking ideas receive credit, and valuing artistic influence with fair compensation. Exposure doesn’t pay the bills—paychecks should reflect the power artists hold in shaping the world around us.

Contact Info:

- Website: https://www.thebrieshowstudio.com

- Instagram: @the.brie.show

- Other: Substack: https://thebrieshowstudio.substack.com/?utm_source=substack&utm_medium=web&utm_campaign=substack_profile

Image Credits

Marisa Savegnago