We were lucky to catch up with Brandon Stosuy recently and have shared our conversation below.

Alright, Brandon thanks for taking the time to share your stories and insights with us today. Are you able to earn a full-time living from your creative work? If so, can you walk us through your journey and how you made it happen?

At this point I do make a full-time living from my creative work– that said, it took years of juggling multiple jobs until this came together.

I grew up solidly working class in a small farming town in the Pine Barrens (population 800) where I got my first job, picking blueberries, when I was 13. We were paid by how much we picked, not hourly. This taught me a lot, really. I learned you didn’t get paid for just standing around… you had to be useful and you had to keep going.

After that, I had one kind of a job or another (or multiple jobs) until deep into adulthood: I’ve worked construction, at gas stations (graveyard shift), at a second-run movie theater, at a garden center, at a convenience store, at different book stores, etc. For a time I was helping a guy write a book about how Jesus faked the crucifixion. I helped another person work on an action film they wrote about themselves (casting themself as the charismatic lead). I once tried to sit down and list all of my jobs and I finally gave up… I worked so many places over the years.

I had to take what work I could get… I never had a school experience where I could focus entirely on my studies. When I was in college in New Brunswick, NJ, I worked at an independent record store in addition to work study and at the college radio station. In grad school in Buffalo I worked in the rare books room and as an assistant for the artist and musician, Tony Conrad, who became an important friend and mentor to me.

I got really used to juggling things. It’s honestly why I still do so many side projects: My creative brain was shaped by being a person who had to work a day job, and so I’m not someone who wants to go on a creative retreat or to a focused residency. I’m not sure that kind of thing would be helpful to me– I need the chaos of the everyday to get my stuff done (it’s how I think of ideas and stay inspired).

I only started making money off my writing after I was done with grad school and became a freelancer. During that time, I was working for an art dealer and as an archivist at NYU. I got lucky because I was one of the first people to work on, and write for, Pitchfork (the online music publication) and as it grew, it slowly became a proper job. This, too, was not overnight, but in time, I was able to leave the art dealer, leave NYU, and start working full time for Pitchfork (with a short stint at Stereogum, too).

I was at Pitchfork for a decade before I left to start my own website, The Creative Independent. That’s what I do today.

I”m not sure I could have sped up the process, to be honest. I had no financial safety net, and so I had to focus on things that would pay the bills. This wasn’t always the most exciting or satisfying work. I lucked out with Pitchfork taking off, and I lucked out with TCI. I started that site at a time when people were looking for something different– something slower, more thoughtful, more evergreen, more positive. The success of TCI has been incredible, and I think a lot of it has to do with when I started it… so, all said, even though it took a long time to get to where I am, I think the timing was, in fact, perfect.

These days, I do make a living off of the site, but I still manage some musicians and collaborate with artists on live events, etc.– because, again, I like beings busy. It’s how I grew up. You can take the kid away from the farm, but you can’t take the farm out of him… I really believe that. I like (and need, I think) having things to check off a list.

As always, we appreciate you sharing your insights and we’ve got a few more questions for you, but before we get to all of that can you take a minute to introduce yourself and give our readers some of your back background and context?

My name is Brandon Stosuy. I’m the founder and editor in chief of The Creative Independent.

I previously worked as director of Editorial Operations at the music publication, Pitchfork, and I was senior editor at Stereogum.

I curate the annual Basilica SoundScape festival in Hudson, New York with my friend, the musician and writer and curator, Melissa auf Der Maur. We just had our 15 installment of Soundscape this past September. It’s been labelled an “anti-festival” by some folks because we don’t follow the usual festival format. We also make it happen each year with no corporate sponsors. Our hope is to create an actual community event that’s not influenced by algorithms or advertising.

I grew up making a zine, which I started when I was 13. I did a number of issues over a number of years. As an adult: My anthology, Up is Up, But So Is Down: New York’s Downtown Literary Scene, 1974-1992 was published by NYU Press in 2006, and was a 2006 Village Voice book of the year. I’m also the author of three books on creativity, Make Time for Creativity, Stay Inspired, How to Fail Successfully (all published by Abrams) and two children’s books, Music Is… and We Are Music (both published by Simon & Schuster). My most recent book is the anthology, Sad Happens: A Celebration Of Tears, also out on Simon & Schuster. It features essays by 150 people (including myself) about crying.

As far as what I’m most proud of, I think I’d say The Creative Independent…

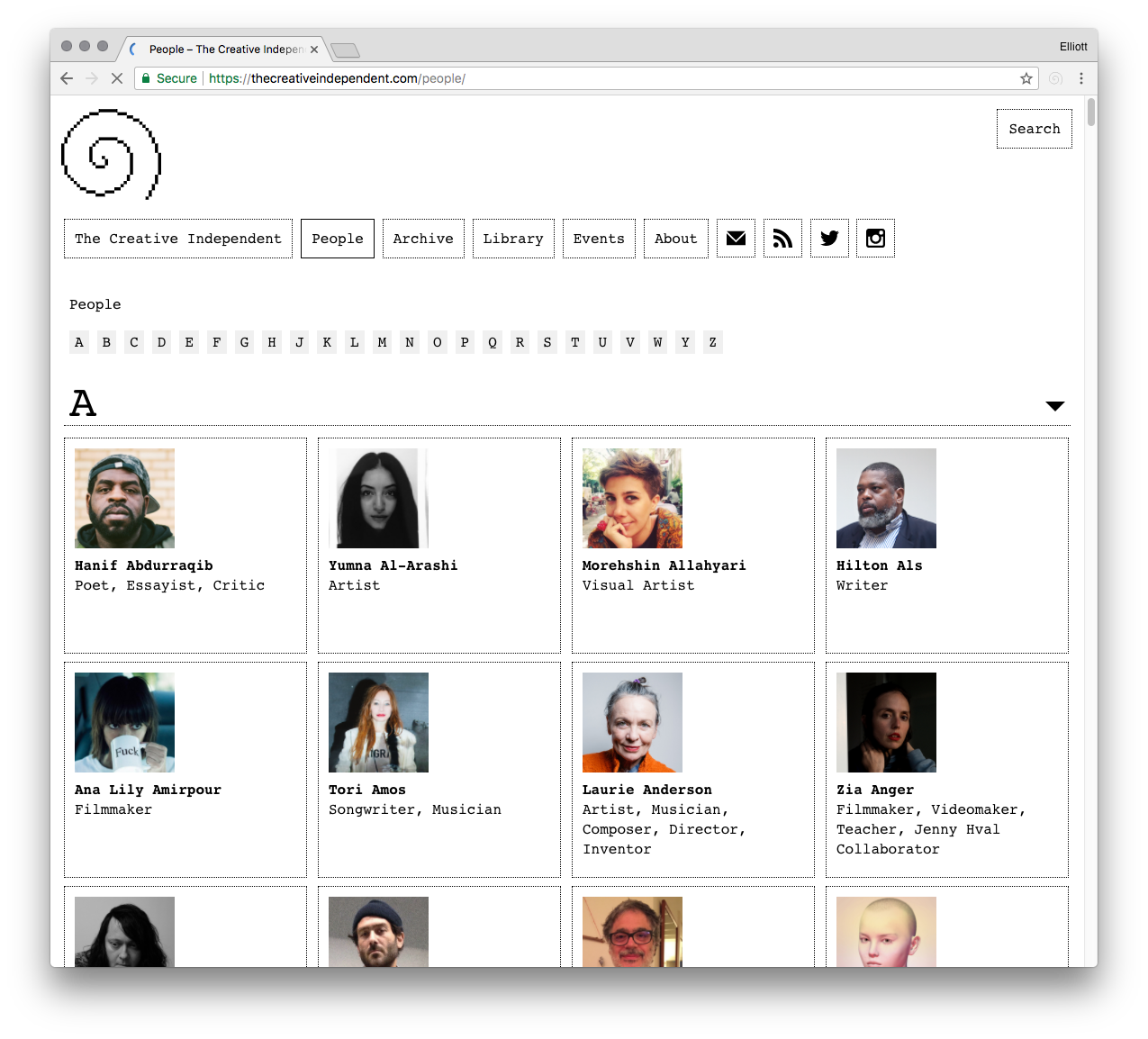

I launched The Creative Independent in September 2016 with the goal of educating, inspiring, and growing the community of people who create or dream of creating. I wanted it to be a website, but more than that, too. I viewed it as a hub and potential community with related events and publications.

When I drew up the idea for TCI, I thought about being a teenager, and how I’d stumbled along, figuring out how to do things by myself before I had any kind of blueprint. I’d found that blueprint in zines and punk. I imagined TCI as that sort of blueprint, in the digital age, for people who want to make things.

When I was 13, I put on hardcore shows in my dad’s backyard largely because we lived in a rural farming town in New Jersey and it was the only real option if I wanted to see a show. There was plenty of space, and hay trucks I could eventually use for stages (it turned out), but no actual venues. So I made one.

These days, I’m an experience curator, I guess, who’s collaborated with a variety of artists in different disciplines, across art and music and books, at venues like MoMA PS1, the Broad Museum, the Whitney Museum, the Hirshhorn, the New Museum, and galleries and various underground spaces. I‘ve been collaborating with the visual artist Matthew Barney for the last 15 years on an underground venue in Long Island City we call REMAINS. Quite differently, when I worked at Pitchfork, I booked all the events at the very above-ground SXSW.

As a kid, I had no idea what I was doing, but I was able to piece things together with intuition, youthful energy, and the help of paper zines, anecdotes from friends, and a resource like the Berkeley, California newsprint zine Maximum Rock n Roll’s annual life guide, the clearly titled, Book Your Own Fuckin’ Life.

BYOFL was printed on the kind of inky paper that left stains on your fingers, which felt poetic to me at the time. It was divided by State, and suggested where to book shows, shop for zines, find a crash pad, or, among other things, get a vegetarian-friendly lunch the next time you visited Arizona or Michigan or Texas.

It was small, and hard to find, and when I mention it today, many people have no idea what I’m talking about– but it was a huge inspiration for me and my friends. I ended up using it to organize a month-long tour for my band when I was in college, and when I needed to press records for the label I started, or find distribution for the zine I wrote. It was as useful as you made it.

That said, it did have limitations. It had to be updated each year, because the places it suggested often closed or changed addresses or were turned into less interesting versions of themselves. As I got older, I realized it was more of a punk rock telephone book or yellow pages than an actual “how to.” It told you where things where, and who to get in touch with, but what if you wanted to do something on your own? It gave you the tools for finding a community, but it didn’t really offer the exact steps to doings things with your own hands.

It’s important to outgrow your influences, and that’s the gap I imagined filing with TCI. I wanted it to be an evergreen resource and to provide the tools you needed to make things yourself. I wanted to avoid it being a here-today-offline-tomorrow website or a news-cycle-addicted blog.

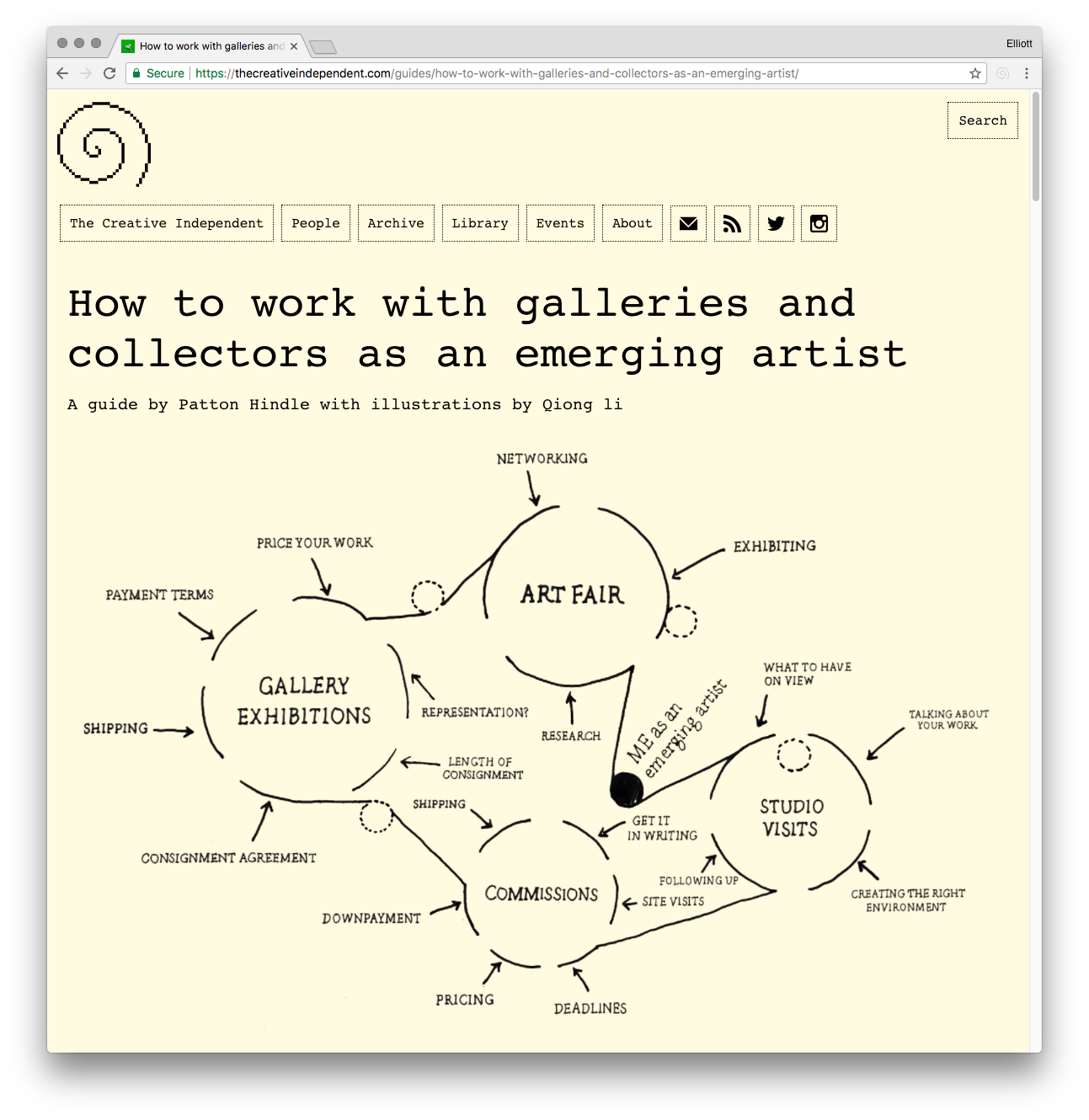

Almost a decade into the project, I publish an interview a day with people from across disciplines, along with how-to guides and essays. The site operates outside of the news cycle because I’m hoping to create material that will be just as useful in 20 years as it is now. I see it as a growing resource of emotional and practical guidance—I’ve printed guides on making time for creative work as well as how to do your taxes.

Sometimes it’s just as important to offer moral support as it is to show someone how to record their own podcast or build their own website.

Today, there’s so much on the web, but, in my mind, not enough of it connects or gives back to the culture it writes or thinks about. Much of it seems to exist alone and in competition with what’s around it. Or, just to make a buck. People think in terms of clicks and not enough about collaboration or community.

I’m interested in the impulse to go for it and do it yourself, and to better a community in the process. I’m not thinking of DIY as a marketing slogan. I’m thinking of it as actually learning how to create something and then, in the spirit of punk and underground culture, passing on that knowledge so someone else knows how to do it, too.

I thought of TCI as having the potential to be something that affects people’s lives outside of a diversion at work or a screen to tap on while riding the subway. It could actually assist in some form of self-sufficiency.

Over the last nine years, we’ve put on dozens of events with partners like MoMA PS1 and Rhizome. We’ve self-published a Japanese-language zine, a Spanish-language zine, and six English-language zines. We’ve collaborated with Are.na on a collection about using the internet mindfully and a collection with Ballroom Marfa about what it means to be an artist in the age of the current environmental crisis.

And, the site has grown considerably.

There’s a large readership and community around it.

I’m not one to care too much about numbers, but I do care about positive sentiment: The TCI instagram has 136,000 followers and every day we have dozens and dozens of almost entirely positive comments… something I find incredible… and beautiful!

The site’s been featured in numerous art and culture and news publications and sites. Matt Berninger from the National wrote to tell us he’s set TCI as his homepage because he finds it calming.

All of this happened by following the original blueprint, and then refining that blueprint, but never changing courses or sacrificing the original mission. (For instance, as ridiculous as it may seem, we’ve yet to embed a video, because early on, I realized embedded videos usually have an advertisement tied to them. Plus, they look kind of wonky.)

This is something I tell young artists all the time: Stick to the thing you care about. Don’t cut corners or shift your approach because you think it’ll get you somewhere faster… stay true to your vision. It really will be worth it in the end. No lie.

We’d love to hear a story of resilience from your journey.

I grew up not knowing of a single artist who made a living from artistic work. I really had no plans to make a living from my creative work… I didn’t think it was possible.

When I first tried to pivot from juggling non-creative jobs to becoming a freelance writer, I sent out my clips to a variety of publication and heard absolutely nothing back from any of them. I could have given up here, for sure. At the time, I was talking to a friend about it, and he suggested that I send the stuff out again, because he thought I had the timing wrong when I initially wrote the publications– he told me that it was the end of the fiscal year, they’d likely used up their budgets, and it’d be a good idea to give it another go. So I did. This time people did get back and I got my first few freelance jobs….and then things kept growing. I think back now and then to that moment and wonder what would’ve happened if I’d just given up.

Connected to this: As mentioned in previous answers, it took me a long time to make a full-time living off of my creative work. I think a big part of this was having grown up working class and not really knowing anyone else who made a living as an artist. I had no frame of reference.

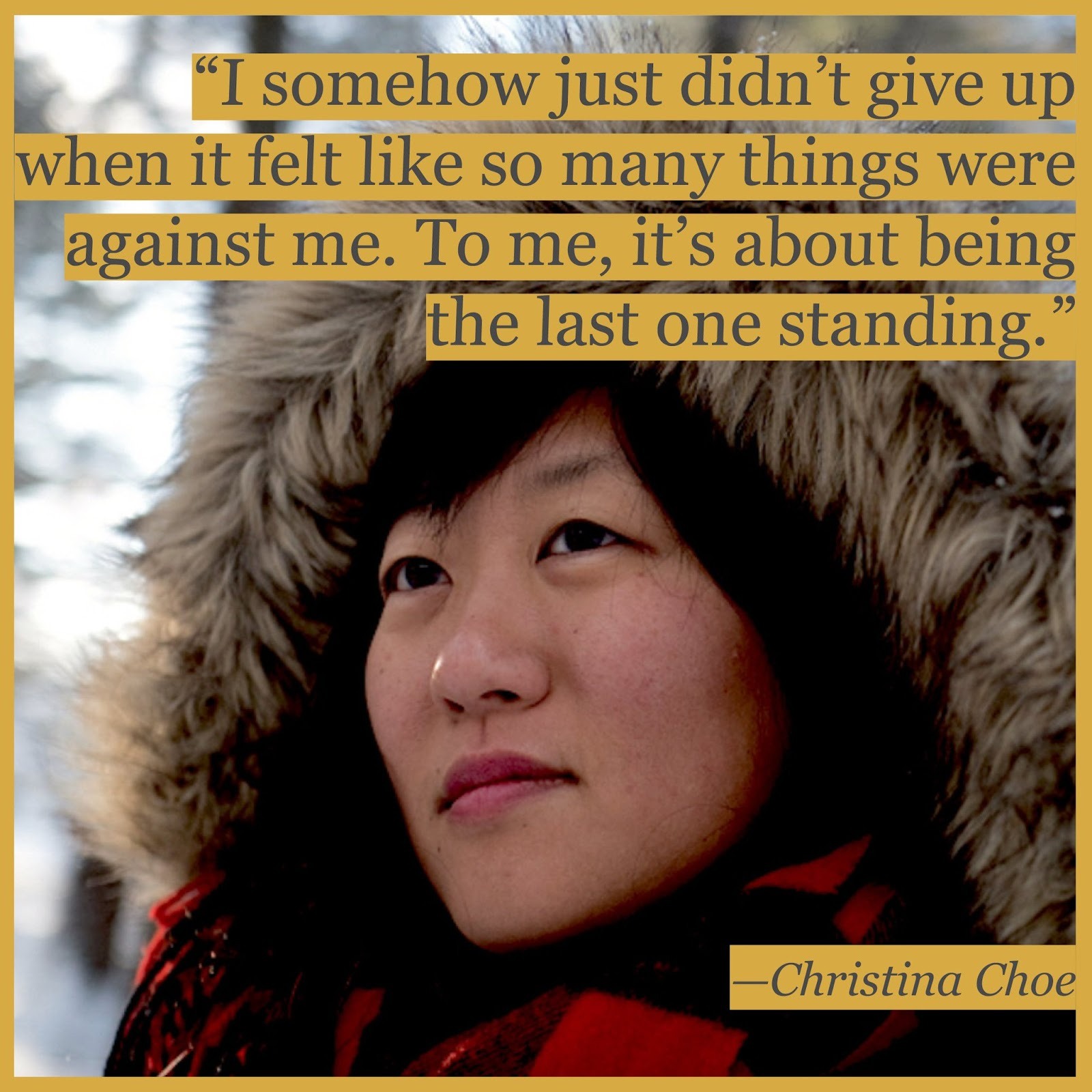

I did have a really dear friend, Kenny Doren, who grew up in a similar situation as me. He’d come of age in Alberta, Canada, but outside of these different geographies, we had a number of overlaps. We met because, for a few years, I was living in Lethbridge, Alberta. At the time, I had an idea for a film and applied for some funding to make it…. and somehow I got it. A year or so later, while I was working at a small art gallery, the Southern Alberta Art Gallery, I met Kenny, and it turned out he was a judge for that funding. We hit it off and became good friends.

Years later, when he was visiting me in NYC, and I was juggling a bunch of jobs and feeling really down, he told me that I was too good a writer to waste my time with all of these other day jobs. He knew I had no safety net– no rich parents or savings– and yet he still had faith in me. This meant so much. “Quit your day job” is an easy enough thing for people to say when the haven’t come from the same sort of situation as you… he did and still he thought I could do it. So, yeah, I started scaling back my other work and focusing on my writing, and slowly, but surely it worked.

Kenny died very young, from pancreatic cancer. His wife, Gayle, asked me to give the eulogy at his funeral. One of the things I spoke about when I did was how Kenny was the kind of friend who could give you the courage to do things that felt impossible because of how honest and caring he was… You just knew he wasn’t lying and had no outside interests or motivations in why he’d tell you something… he was a pure, kind human being. One of the last time we talked, before he passed, he told me he was glad I’d taken his advice, and that he was proud of me. He also told me that his own short life (he knew he was dying) was another example of why we really do have to follow our hearts and pursue the things that matter most to us. He kept giving pep talks, all the way til the end.

For you, what’s the most rewarding aspect of being a creative?

I love that now that I’ve been doing this for some time, I have younger artists who reach out and ask me for an opinion or advice. I think back to someone like Kenny and the impact he had on me, or Tony Conrad when I was in Buffalo. Or any number of mentors I had when I was younger.

In that vein, I enjoy doing conversations and lectures and panels at schools. (I recently did one at Hunter College, for example, as well as one for the design team at The NY Times).

Or, a couple of weeks ago I had a reading as part of a series called Late to the Party Press. It’s curated by two of TCI contributors, Sophy Drouin and Madeline Howard. It was at Happier Apartment on Canal Street in Manhattan. They asked me to read last, and it was to a packed room of probably 200 people, most of them in their early 20s. Folks listened in silence, not looking at their phones. Afterwards, a handful of them spoke to me for a good 45 minutes, until It was time for me to hop on the subway back to Brooklyn.

I appreciated how much folks cared and how they wanted to dig deeper afterwards. That’s really rewarding to me.

For that reading, I read one of my own pieces, and then used my time up there as an opportunity to introduce people to the work of two of my friends– Laura Brown and Maria Owen. They’re both such great writers and people. I read something by each of them, gave the context, explained who they were, etc. (I’ve been working with Maria on a series of events that feel really important to me– the piece I read by her introduced our concept of it, publicly, for the first time.)

I feel lucky to be where I am now. Coming from where I came, it kind of makes no sense that it worked out. So, yeah, what I really want to do is pay it all forward– helping folks try to figure out their own creative paths.

All said, I’m still the 13 year old kid making a zine. I just have more resources now….and I want to share them as much as possible, along with my platform.

Contact Info:

- Website: http://www.thecreativeindpendent.com

- Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/thecreativeindependent

- Linkedin: https://www.linkedin.com/in/brandon-stosuy-84467437b/

- Other: TCI Bluesky: thecreativeindependent.com