We caught up with the brilliant and insightful Aurora Robson a few weeks ago and have shared our conversation below.

Alright, Aurora thanks for taking the time to share your stories and insights with us today. Can you open up about a risk you’ve taken – what it was like taking that risk, why you took the risk and how it turned out?

After overcoming a challenging childhood (a father in and out of jail being the tip of that iceberg) and a divorce from an artist I married at 18 (who miraculously never gave me STDs), I turned my life around. I found myself living in Brooklyn as a Columbia graduate with a mountain of student loan debt, but I had a “great job” and was making good money working at Viacom (MTV Networks) in Manhattan. I got to travel and work with crews all over the world. I got swag bags from Kiehl’s and Puma, met a lot of celebrities, had great co-workers, and a chill boss who had a crush on me. (Unreciprocated.) I was about to go from freelance to full-time with benefits, art directing/production designing sets for special events. Sets that would be used for an evening, then just get thrown out.

I felt like a flea on the underbelly of a giant corporate beast that might discover me and scratch me to pieces at any given moment.

I decided to save enough money to survive for 6 months. I built an additional tiny bedroom for myself in the loft I was renting, and rented out my larger bedroom, which cut the rent down for all of us. I took a massive leap. I was so excited, terrified, and maladjusted on many levels. I was working through unresolved trauma in my paintings and works on paper. I used a common area in the loft for my painting/art studio and worked all day while my roommates were at school or work. I knew that if I didn’t take this risk, I had zero chance of personal fulfillment, would live my life with no sense of purpose, and I would run a higher risk of becoming a burden on society. I resolved to try my hand, all in, full-time, without any distractions, at being an artist. I gave it all my waking hours and all my focus and energy. I created a body of work, a website, and dove in.

It has been over two decades, and I have been essentially a full-time (feast or famine) artist ever since. 100% worth the risk.

Great, appreciate you sharing that with us. Before we ask you to share more of your insights, can you take a moment to introduce yourself and how you got to where you are today to our readers.

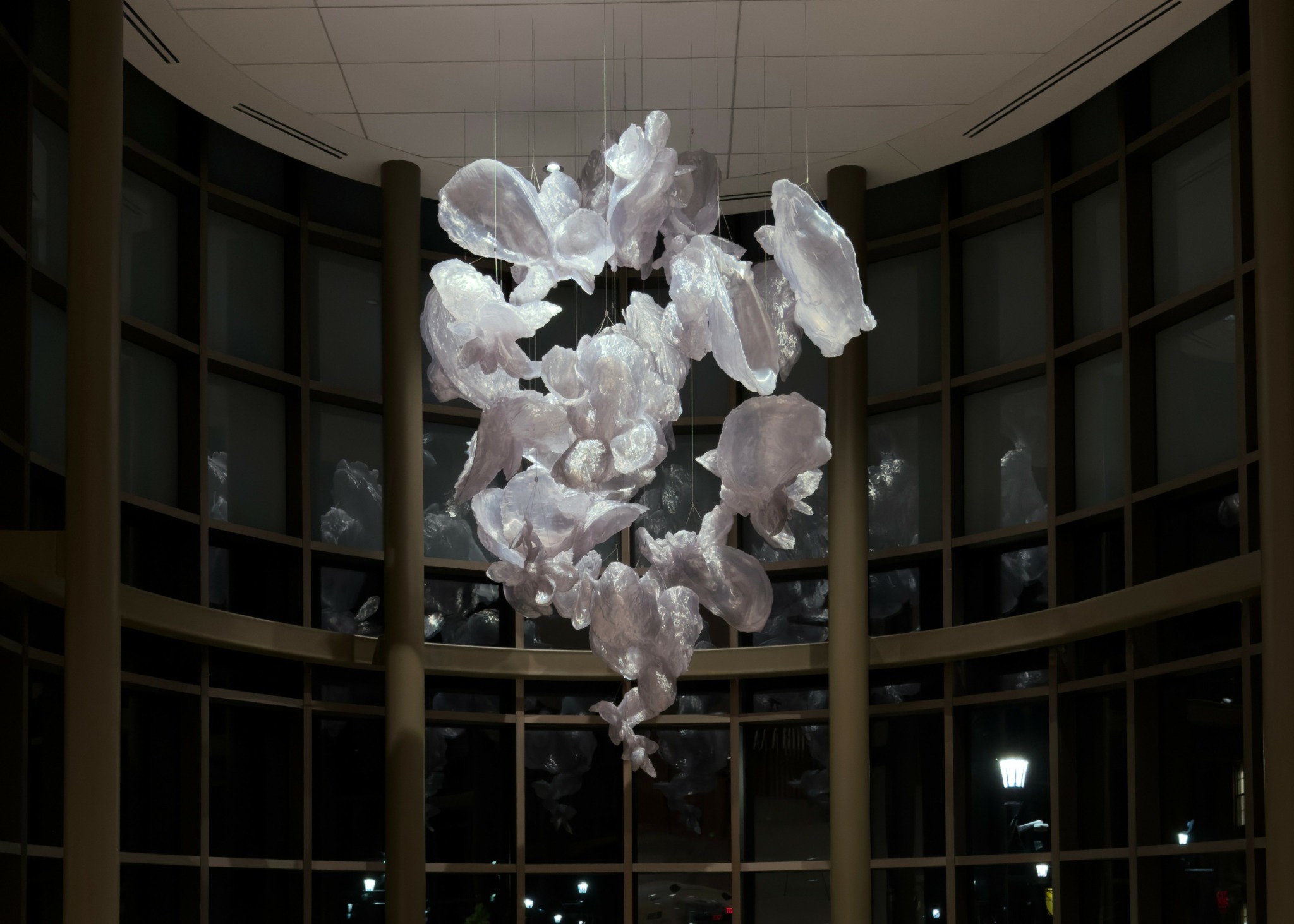

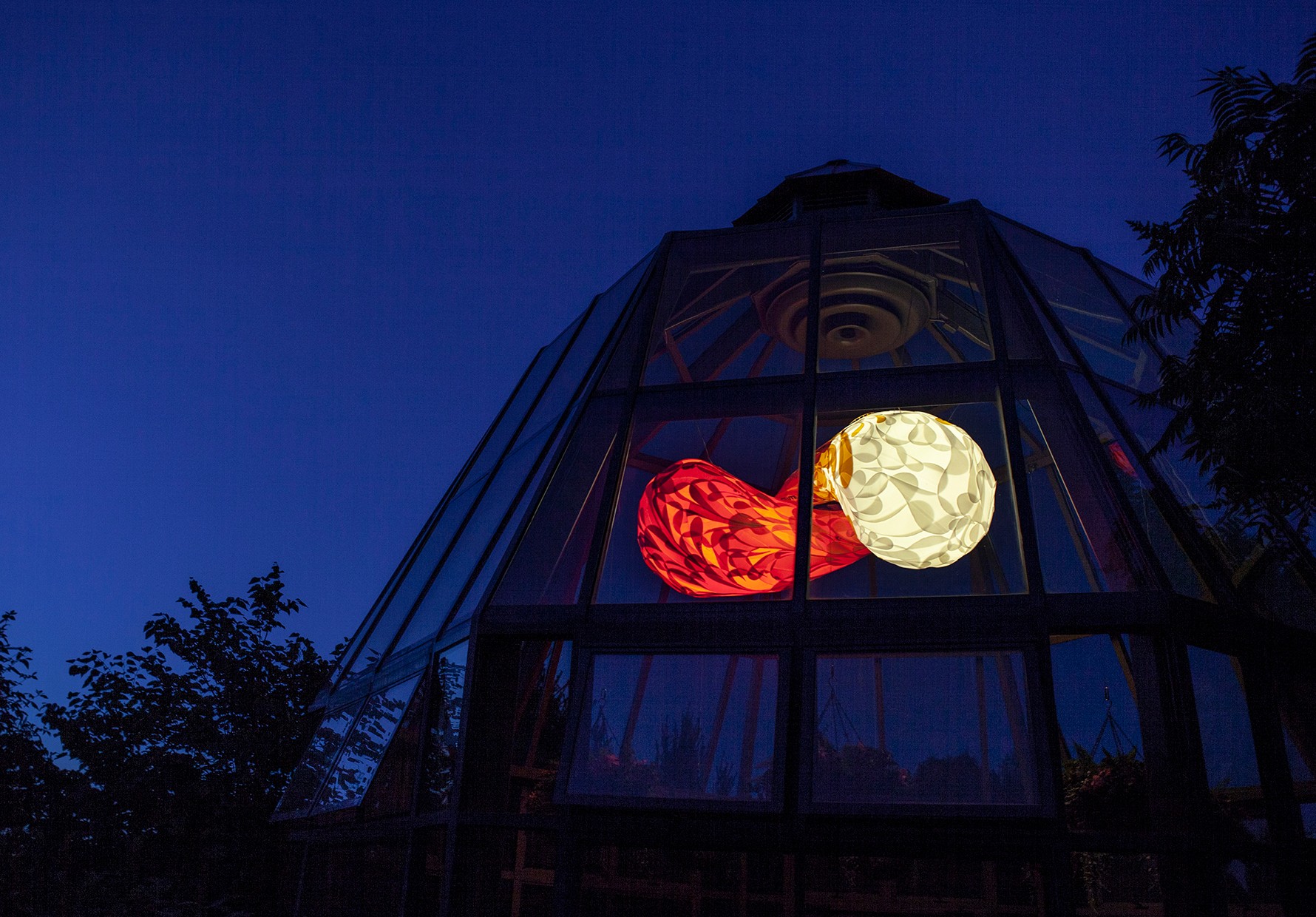

I was born in Toronto but grew up in Hawaii, on Maui. It sounds idyllic, and in a way it was, but I lived there as an illegal alien with an unstable and scary home life. Things at school were also awful. I was a minority at public schools where white people were discriminated against. It was a high contrast situation — exquisite nature, combined with terrifying home life and stress at school. My family often had no money because, as much as she wanted to, my mother couldn’t get a job being Canadian. She was essentially a hostage in our home. I started doing jobs like pulling weeds for neighbors for money so I could buy new clothes. I made my first big chunk of money by winning a poster contest. That planted a seed for me. Fast forward to my early teens, my dad gets arrested again, and my family is deported back to Canada. I lived in Toronto for a while, but when my dad got released early from jail. My mother fled, having filed for divorce while he was incarcerated. I suddenly had to either pay rent and figure out how to survive on my own, or risk going to an orphanage. So, at fifteen, I dropped out of high school and started working. A decade later, I am living and working in NYC, doing all manner of jobs, bartending, waitressing, hostessing, antique restoration, dog-walking, sous chef, art directing at an umbrella factory, working as a house painter, a scenic painter, a welder, and a graphic designer. I sang in a few bands, taught myself to play the upright bass and guitar, got divorced, applied to and got into Columbia University, graduated with high honors, and shortly after met the father of my children and love of my life while we were working on the set for “Strangers with Candy”, a Comedy Central show starring Amy Sedaris and Steven Colbert. I was freelancing as a scenic artist. All this time, I was making art, collages, paintings, and sculptures. I was writing, seeing art, dreaming art, loving art, and immersed in art in NYC. When I started my full-time art practice, I was making works on paper and paintings that were inspired by recurring nightmares I had when I was a kid in Hawaii, depicting them as a way to process them, transform them into something I wanted to spend time with – they were curvilinear, endless knots that I would find myself tiny and trapped in. The negative spaces between the lines were gelatinous, diaphanous blobs that would encroach like they were going to suffocate me. I found ways to illustrate them that subjugated their negative qualities for me. One sunny day, gazing out of my street level window, I noticed a correlation between elements in my 2D work and components in the piles of rubbish outside my studio window in Brooklyn. The clear blobs and amorphous shapes of plastic bottles had formal attributes that related to the forms in my paintings, so I started playing with plastic bottles. Almost immediately, the world seemed to respond to what I was doing, and doors opened up for me. I wasn’t just transforming my own personal nightmares, but transforming a global nightmare. Since then, I have learned a lot about plastic pollution, it has almost taken over my art practice. The more I’ve learned about it the more I become dedicated to it. Initially, it seemed preposterous to me that no artists in galleries or museums at the time were doing anything with post-consumer plastic, when it was so everywhere. Nobody was talking about it, so I started talking about it, but more than that, I started walking the walk by actually making art out of it. It became my primary medium. Now I have methods for cleaning it, cutting it, shaping it, fastening it, weaving it, threading with it, sewing it, ultrasonic welding it, and injection welding it, and most recently, 3D-printing with it. To me, making work from this material is a way to sequester it, to soften the edges between culture and nature. It allows people to invest in art that serves life directly while revealing their own beautiful moral fabric, while creating mnemonic devices to remind people to reduce their own plastic footprints. I utilize post-industrial and post-consumer plastic to keep it out of landfills (or our failing plastic recycling systems). I work to create hope from chaos and apathy. I work to inspire people to take action, including myself.

Do you think there is something that non-creatives might struggle to understand about your journey as a creative? Maybe you can shed some light?

The instant I started gaining momentum with my art, I became pregnant with my first child. It was the early 2000s when almost no successful women artists were also mothers. It was discouraged, if not discriminated against. When I dared to have a second child, collectors of mine became enraged and ghosted me.

I know I’ve helped establish a path for this to be easier for generations of women artists, but it hasn’t been easy. Having two children while being a full-time practicing artist has meant that I haven’t been able to dedicate much time to anything outside of my practice and my family. Being a parent is a notoriously challenging job, as is being an artist, and I take both of my jobs very seriously. I have no regrets.

However, I have not had consistent support or representation from any commercial galleries, so I’ve had to cultivate a lot of faith in myself and my practice. People often assume that I am rolling in resources because of the successes I have had by creating some very large-scale artworks over the course of my career, and because of how “Googleable” I’ve become – most people don’t understand that there is almost no stability or consistent schedule for artists or that by simply being artists, we are providing a service to broaden the collective cultural landscape which makes life richer, more beautiful and interesting for everyone. I’ve had people ask me how I make a living, not understanding that my work pays our bills. They often don’t realize that I sell my work, and that I am delighted and honored when people purchase it. There is no net under me when I fall, and we all fall sometimes. I wish more people understood that being an artist means you have to practice being vulnerable, sensitive, and strong at the same time. The more sensitive you are, the better you are at making art, but also the more vulnerable you become, so in order to manage life this way, you have to have a lot of grit. It is a strange life, awkward to talk to other parents at PTA meetings who have normal 9-5 “jobs” and difficult to make any plans because opportunities come when they do.

Sometimes it is almost impossible to relate to people with full-time jobs who don’t spend any time at all in the “zone” that keeps me sane, the space I go to when I am making art. It is like going back to the well for me. It is the most nourishing, empowering, exciting, radical, experimental, humbling, and exhilarating thing to do. I go to a place beyond thinking and feeling. Linear time has no business there. It is a sensory practice that creates a connective tissue between imagination and reality. Taking a vision and making it reality is like communing with some kind of divine energy. The “zone” is full of energy, so rich and complex that it can completely consume us.

Do you have any insights you can share related to maintaining high team morale?

People love to do things they are naturally good at, and everyone is naturally good at something. When I have a project that is big enough to warrant a big team, I try people out at different tasks until I find the one they can do most easily. If there is nothing obvious, I keep moving them around until something makes sense for them. That way, when they go home each day, they will have a feeling of joy and accomplishment instead of feeling like they have been struggling all day. When someone is struggling to master a task and you’ve tried to teach or explain it to them more than two times, ask someone else on the team who has mastered the task to teach them. Sometimes, a different teacher can get the same lesson across to someone more effectively by using a slightly different approach. If someone is doing really poorly at something, tell them delicately in private so that they aren’t humiliated, and ask them what they think would help. When we recognize and acknowledge our own mistakes or weaknesses, we are much more equipped to overcome them. Good music helps keep people in a rhythm in the studio, l like to invite people working to take turns DJing for the group — if they are comfortable doing that. I always offer structure, lunch at the same time every day, normal business hours, clear expectations, and clear goals. I recommend being as transparent as possible without overwhelming people. Smile when you see people come into work. It is good fortune to be able to employ people through an art practice. Praise people for doing a good job, in public and in private.

Contact Info:

- Website: https://www.aurorarobson.com

- Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/aurorarobson

- Linkedin: https://www.linkedin.com/in/aurora-robson-3304157/

Image Credits

All photographs by Marshall Coles