Alright – so today we’ve got the honor of introducing you to Ashleigh Sumner. We think you’ll enjoy our conversation, we’ve shared it below.

Alright, Ashleigh thanks for taking the time to share your stories and insights with us today. How did you learn to do what you do? Knowing what you know now, what could you have done to speed up your learning process? What skills do you think were most essential? What obstacles stood in the way of learning more?

It has been said, accessibility is the gateway to discovery. I’ve often contemplated the notion of accessibility in my own path in the arts which hasn’t been linear. Initially, my journey began in theatre due to accessibility. During the 1990s, I grew up in a rural community in North Carolina forty-five minutes outside the city of Charlotte. Even though I had a tremendous aptitude for art as a child, the idea of studying to be a painter was a completely unimaginable concept. The only artists I ever heard of – Matisse, Picasso, and Monet – were all men and dead. Like many women, I simply did not see myself reflected in the visual arts at that time. Even though I spent my life surrounded by the exquisite quilts created by my great grandmothers, those masterpieces weren’t recognized by the culture for the art we now know them to be. It’s possible if I grew up in an urban area, I would have been exposed to living artists with working studios, but those spaces weren’t accessible in the rural suburbs of Charlotte, North Carolina. What was available to me, thanks to my mother, was theatre. My mother would make sure her children attended every touring Broadway show that stopped in Charlotte. Because of this exposure, theatre would be my foundation and path forward to the visual arts.

Looking back, that transition from the stage to canvas makes a lot of sense when you really start to dig into the emotional, physical, and conceptual threads that tie acting and painting together. My background as an actor helped develop a sensitivity to rhythm, emotional pacing, contrast, tension, and most especially, instinct. All the skills I learned with the Strasberg Method on stage now inform how I lay down paint, layer materials and how I respond to a surface in the studio. Frankly, so much of my studio practice has been learned through trial and error. I think most people may not realize there’s so much “failure” that happens in any artist’s studio during the unseen hours. I’ve found that failure is my greatest teacher because it breaks the myth of control. It pushes me to keep exploring until I finally discover what I’m seeking in a piece or what a piece is trying to reveal. It forces a pause. While I don’t like failure and I’m never comfortable with it, I’ve learned to respect it as an integral part of the process.

I think when I was younger, the greatest obstacle to learning more was the continuous cycle of art fairs. I know that sounds crazy because who doesn’t want to participate in art fairs?! Let me be clear; it’s an honor to be selected with a gallery to participate in an art fair. However, personally for me, that constant treadmill kept me from taking the time and space to explore beyond what I was consistently exhibiting in those venues. Creatively, I felt like I was on rinse and repeat. When the pandemic arrived in 2020 and everything came to a stand-still, I had room to come to terms with how I wanted to move forward as an artist and the type of work I would explore from that moment on.

Ashleigh , love having you share your insights with us. Before we ask you more questions, maybe you can take a moment to introduce yourself to our readers who might have missed our earlier conversations?

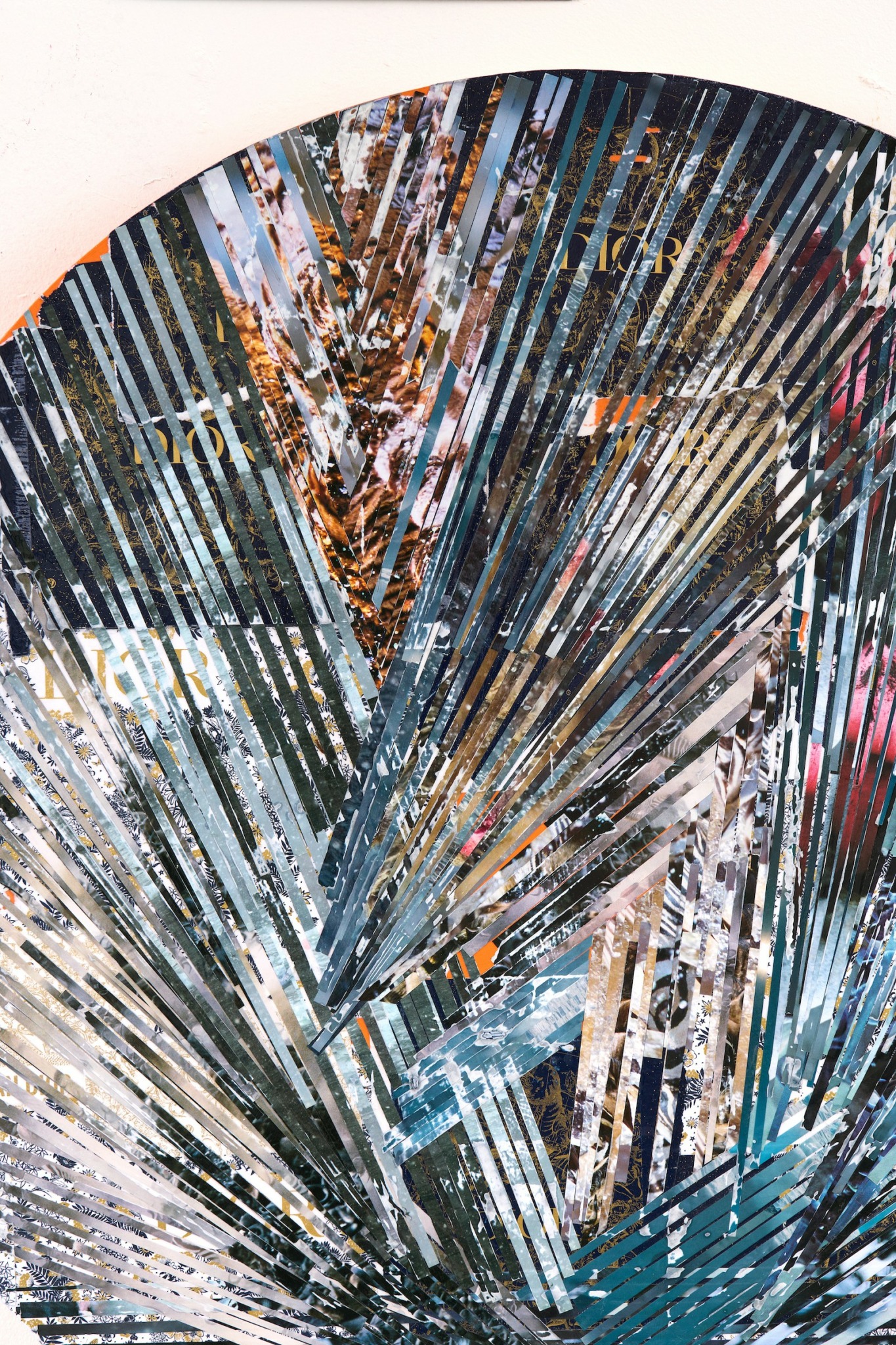

In my latest work, I’m repurposing street posters, luxury brand shopping bags, and Nike shoe boxes into multi-layered collages. To me, these fragments of paper are a study in the cultural remains we leave behind. They also reflect our society, values and our most American of past-times, consumerism. This new series is an abstract exploration into our relationship with corporate branding. I’m curious how these companies drive cultural discourse, establish economic hierarchy, and influence our personal identities through consumption. My generation grew up during the height of Air Jordan and to this day, I am still hypnotized by the Nike representation of self-mastery, champions, and transcendentalism. It’s universally accepted that Dior and Gucci are more than designer brands. They are symbols of luxury and economic upward mobility.

It should be noted, the urge to display wealth and social position through consumer goods is nothing new or purely American. In the 1550’s, pineapples were a rare luxury and considered the ultimate display of European and British opulence. Yet, mass consumerism coupled with branding is the outcome of an industrialized, post WWII United States. No artist understood the American relationship to commercial advertising better than Andy Warhol. With Campbell Soup Cans and Coke Bottles, Warhol critiqued an expanding consumer-driven society in a mid-century America. His work created a provoking dialogue on the societal effects of mass media advertising (television) coupled with industrialized-consumerism and identity. Today, we live in the era of social media, endless scrolling advertisements, a widening economic gap, and an amplified identification to extreme wealth. Like Warhol, I’m exploring the influence of our modern consumer-culture.

While breaking down countless Nike shoe boxes and luxury brand shopping bags, I was curious how a plain paper bag is considered trash, yet the same paper bag embossed with Gucci or Air Jordan is emotionally considered a treasure. I don’t have a clinical answer to this curiosity, but I’m certain Warhol would say, “It’s gotta be the shoes.”

In your view, what can society to do to best support artists, creatives and a thriving creative ecosystem?

First and foremost, artists need affordable housing and studio space. Artists contribute so much to both the economic and cultural fabric of a city, yet cities do very little for their artists in regards to rising rents. I lived in LA’s Arts District for several years and watched that community get pushed out of the very neighborhood they created in favor of business development. I’ve lived in the Bay Area since 2017 and have witnessed the steady stream of artists, particularly young artists, leave for more affordable areas. I think the solutions to maintaining a healthy, creative ecosystem includes artist housing cooperatives, subsidized workspaces and city-owned properties reserved exclusively for studio space and cultural use. Artists communities have consistently raised home values and business revenue in every neighborhood they settle in – from Dumbo Brooklyn, the LA Arts District, to Oakland – it’s time American artists benefit from the monetary value they create for everyone else.

Of course, artists (like everyone) need affordable health care. In the U.S., this is a big one. Countries with public health care inherently support their artists better.

Lastly, I think how the current United States culture views artists needs to shift. Our society views artists as ornamental but not essential. That needs to change. Society best supports artists when it sees them as workers, historians, healers, educators and visionaries that deserve structural investment, cultural respect and long-term care.

We’d love to hear your thoughts on NFTs. (Note: this is for education/entertainment purposes only, readers should not construe this as advice)

When has Tech helped anyone but themselves?

Contact Info:

- Website: https://www.sumnerartstudio.com/

- Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/ash_sumner/

Image Credits

All photos, with the exception of my personal photo, are taken by Shaun Roberts