We were lucky to catch up with Ari Simon recently and have shared our conversation below.

Ari, thanks for joining us, excited to have you contributing your stories and insights. Was there a moment in your career that meaningfully altered your trajectory? If so, we’d love to hear the backstory.

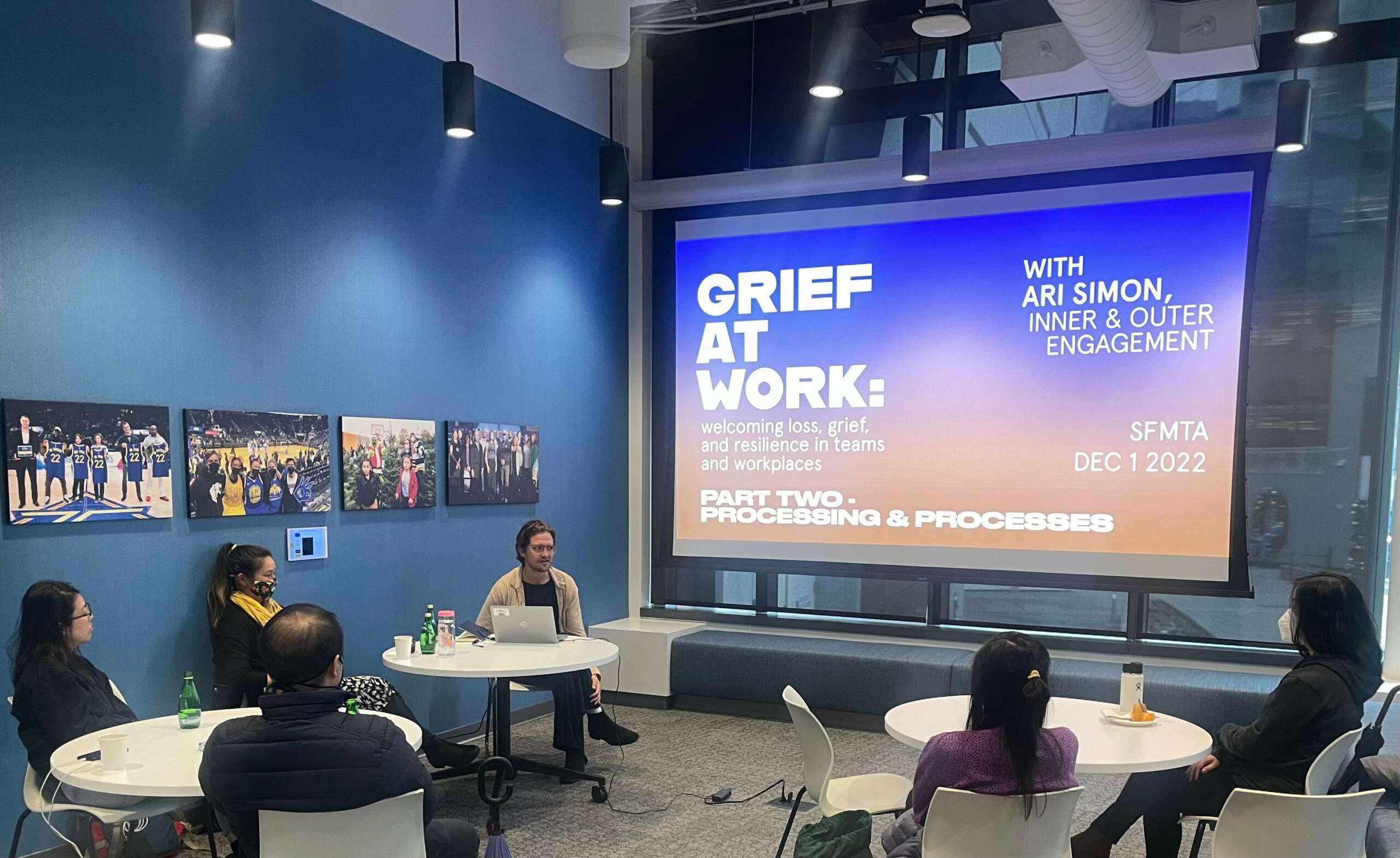

It was about a year after I stopped working for the City of LA when my cousin Tess died while riding her bike to work in San Francisco. My life path was changed by experiencing firsthand the way her community uniquely memorialized her. They took care of each other through this tragic loss, and they took to the streets to demand bike safety improvements. Her employer made space for all her coworkers to process and reflect. The Mayor referred to her by name when subsequently ushering in bike safety improvements in San Francisco’s SoMa neighborhood (A few years later, by pure coincidence, San Francisco’s transportation agency became my first municipal Grief at Work client).

Going through Tess’s death brought me right back to another major loss in my life — the death of my dear friend and roommate who died while we lived together in college. I always knew that experience was life-altering and really difficult. But it took seeing how Tess’ chosen family, communities, and workplaces showed up with their grief to realize how inadequately the university I went to handled my college roommate’s similarly tragic death. No faculty or staff checked up on me after the first week or so. My first and last session at the counseling center ended in tears – the counselor’s, not mine. “Just try and stay focused, and make it to graduation” was the underlying message I felt was all around me and those affected by his death.

This helped me connect more dots. During my time at LA City Hall, it also felt like we never got to pause, reflect, or deeply assess. We’d be going out into communities like Skid Row – encountering the cruelest of conditions, seeing first hand the systemic racism and inequality that fails to keep people housed and healthy. Then w’ed be expected to immediately run to the next meeting, organize a ribbon cutting, do a ride-along with police officers, staff the elected at a labor rally, and do it all again day in and day out. My team moved through the 2016 Election, the death of prominent community members, inappropriate behavior by higher-ups, and plenty of personal life challenges without any real acknowledgment of the toll this work might be taking on us, and the harm we might be causing ourselves and the communities we serve by not slowing down and assessing our actions. It’s the same “just stay focused and make it to the finish line” status quo I experienced at university I attended, too.

I’m the kind of person that loves to move towards a challenge area. So rethinking and relearning how we make space at work and in communities where loss is recognized and grief is normalized, and what we do with that, became my challenge area to deeply explore.

Great, appreciate you sharing that with us. Before we ask you to share more of your insights, can you take a moment to introduce yourself and how you got to where you are today to our readers.

I feel like I wear so many different hats, but the word facilitator feels like the best catch-all. I’m also a grief guide, climate policy convener, engagement strategist, leadership coach, the list goes on. My primary goal is to help clients experience and distribute whole-hearted, life-affirming approaches to navigating complex, challenging issues.

My background is in public policy and civic engagement, with which I played many roles in LA across various topics – from urban planning and placemaking to arts & culture and environmental action. But as my career evolved, I found it increasingly necessary and nearly impossible to show up as my whole self in my work. I felt like I had to sideline my queer, genderfluid self, my spiritual self, and my desires to really go into the depths with people.

It’s partially why I founded my own practice in 2018. Weaving my background in climate planning, policy, and management with training in Zen Buddhism, mindfulness, and end-of-life care, I set out to make navigating loss & change the centerpiece of my work – and I’ve been super lucky to get to apply it a myriad of personal, professional, and policy development realms.

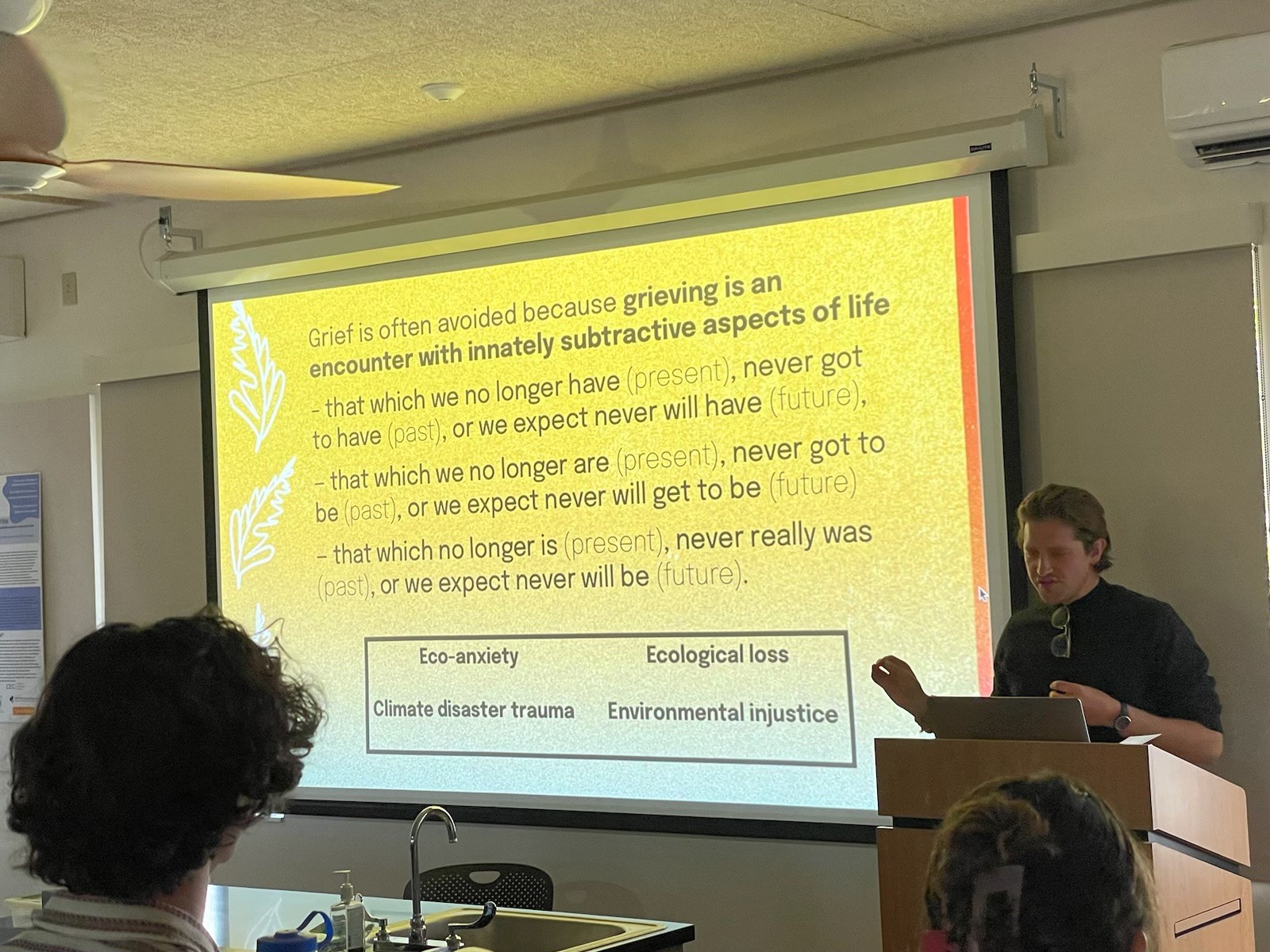

I do this now primarily through my Grief at Work program, where I bring workshops, training, consulting, and coaching to teams, organizations, and communities to help them be more competent, courageous, and caring in the face of loss. Sometimes, workplaces come to me when someone on the team has died or there’s a tragedy that deeply touches the office. Even more so, I’ve found that burnout and disengagement is the alarm bell that’s letting teams know they need to find a different approach. And it’s my personal belief that burnout is all about loss (I also offer workshops on the topic).

But my real strength is working with teams in public-facing, client-serving roles. Because working on complex policy issues and mission-driven work is especially intense — from serving communities facing major loss and systemic injustice, to grim outlooks and seeming to only get farther away from progress. I’ve been in this boat personally and have seen so many other colleagues struggle with this too. But I’ve come to recognize that when grief & loss faced in our working lives is met with skillfulness and support, we can genuinely increase wellbeing, effectiveness, and improved outcomes.

For several years now, I’ve called my coaching practice Coaching at Life’s Edges because that’s where I am best equipped to meet people – at these edge moments in our lives. Amidst a big shift, in a deep well of grief, feeling really perplexed, or even just reaching a new exciting but scary height. I do especially love making grief and grieving the center of my practice (as silly as that may sound) because I think it’s the juiciest prompt for getting us right into this existential place to really see what’s wrong, what’s gone wrong, what hurts, what’s our fear, and what do we need.

Thanks to a lot of working with my own fear and limiting belief, plus a real kick in the butt from the pandemic era, I’ve rolled out several workshops and programs relating to grief & loss these past few years. I created Queering Death as part of NAVEL LA’s Assemblies program in 2020, which grew from there to offer intergenerational LGBTQ+ and allies a space to learn from each other and reimagine death, dying, and grief practices that center queerness. I ran several You’ve Got Male Grief sessions in support and transformation of men and masculine-identifying people. And most recently, I’m now co-leading Grief School – a series of six-week classes with healing artist and emotional alchemy guide Kwonyin (https://www.kwonyin.global/).

Other than training/knowledge, what do you think is most helpful for succeeding in your field?

For me, success and deconditioning go hand in hand. Who’s story of success am I clinging to? And who am I allowing to hold the reign on my sense of confidence? For a long time, I would slip into a ‘fake it til you make it’ mode when I felt I needed to project more confidence and clarity. ‘Faking it’ has some benefits, but I think it can also prolong a lot of our inner pain because it can become an avoidance strategy of feeling through our stuff.

Here’s one example that feels like a true act of kindness I received around this teaching. One of the first projects I was hired to do as a consultant was leading community engagement on a climate action plan for an LA area city. The project lead from the city was such a rockstar (and remains amongst my favorite humans to this day), and I felt I had a lot to prove to her and the rest of team. My imposter syndrome often took the form of me thinking my work practice needs to seem really polished, fully-baked, lots of success stories under my belt, an ability to flaunt expertise, etc.

I will, therefore, never forget the first time we had a one-on-one phone call. I spoke candidly about how I’d love to be able to weave in things like embodiment and grief care into a government planning work. She at some point said to me, “It seems like you’re at a beautiful beginning of figuring out what your work practice is all about.” Upon hearing this at first, I felt so deflated. ‘Oh god, she thinks I’m a total amateur!’ ‘She feels like I haven’t even figured it out yet!’ Imposter syndrome alarm bells blaring.

It took some time for me to realize that her reflection was an unbelievably kind gift. What she was really saying is that I didn’t have to feign having it all figured out to be a deeply valuable part of the project. It was an invitation to simply be with that “beginning,” and not rush and force it forward. I think this is can be really hard to accept, especially when there are bills to pay. But these days, I find so much value and inner ease when I let myself drop the story of having this whole perfectly packaged, perfectly valued-aligned, award-winning blah blah blah, and instead show up honestly as kinda always being in process with defining and refining it as I go.

Any advice for managing a team?

To me, maintaining a great team with strong morale is all about leadership prioritizing the psychological safety and wellbeing of its workforce. I’m biased, but I’ve seen first hand how much of a difference can result from offering room during the workday for people to talk about real feelings, challenges, and issues. When space is held lovingly and compassionately, and people feel like they can actually be a whole, authentic human at work, that helps a lot.

I’ve been co-leading work on this with Shaina Fawn, co-founder of Wellbeing in Entertainment and Creative Arts. In our work, Shaina often speaks about the components of psychological wellbeing: autonomy, quality connections to others, growth & development, ability to meet personal needs, self-acceptance, and meaning & purpose with goals. Even if leadership were to just ask themselves and their employees these in question form, it may be very illuminating (example: “do people who work here feel autonomy? quality connections? growth? like they can meet their personal needs? self-accepting? that our goals are meaningful?”). If the answers to these are “No”, or the questions feel too scary to ask, then it might be time to bring in some loss-competent facilitation.

I’m always amazed that when I lead workplaces through brainstorming out the list of things people need in order to healthily grieve, it’s almost identical to the things we need in order to healthily manage a team. This is especially so in two huge topic areas: time & space, and acknowledgement. I firmly believe the ROI is strong in trusting team members to take time & space when they need it, and recognize that because we live within a deeply unequal system, certain people will have more need for taking time & space than others. One-size-fits-all approaches just don’t work, and can exacerbate painpoints rather than address them.

Contact Info:

- Website: ari.fyi

- Instagram: @ari.fyi

- Linkedin: https://linkedin.com/in/arisimon