Alright – so today we’ve got the honor of introducing you to Ari Okin. We think you’ll enjoy our conversation, we’ve shared it below.

Ari, thanks for joining us, excited to have you contributing your stories and insights. The first dollar you earn is always exciting – it’s like the start of a new chapter and so we’d love to hear about the first time you sold or generated revenue from your creative work?

My freshman year of college, a turf field awaited me outside my dorm hall. Here, I met most of my friends, got much of my homework done, and scouted for every outwardly musical person I could find. With every strum of a guitar on that field, I showed up to introduce myself and play with the strummer. I was eager to find a band to sing with, as I had always wanted to play with a band, ever since I was just a few feet tall. To my luck, more and more instruments began to appear upon the turf: saxophones, flutes, basses, and of course dozens more guitars, were accompanied by eager musicians. After meeting a handful of music-lovers, I put together a cornucopia of an ensemble; mostly beginner musicians with little bandleading knowledge but large personalities and colorful attitudes. We got together a few times a week to rehearse in the UW percussion professor’s office, in which he kindly lent us practice time. I subconsciously stepped into the shoes of our bandleader and took on the role, piecing together arrangements and helping each band member navigate our set. My dear friend Christian, who was our bassist, had a buddy whose band needed an opener, so he threw us into the slot and it was go-time. With this excitement, we also managed our way into a show that the University of Washington was putting on, called Husky Jam.

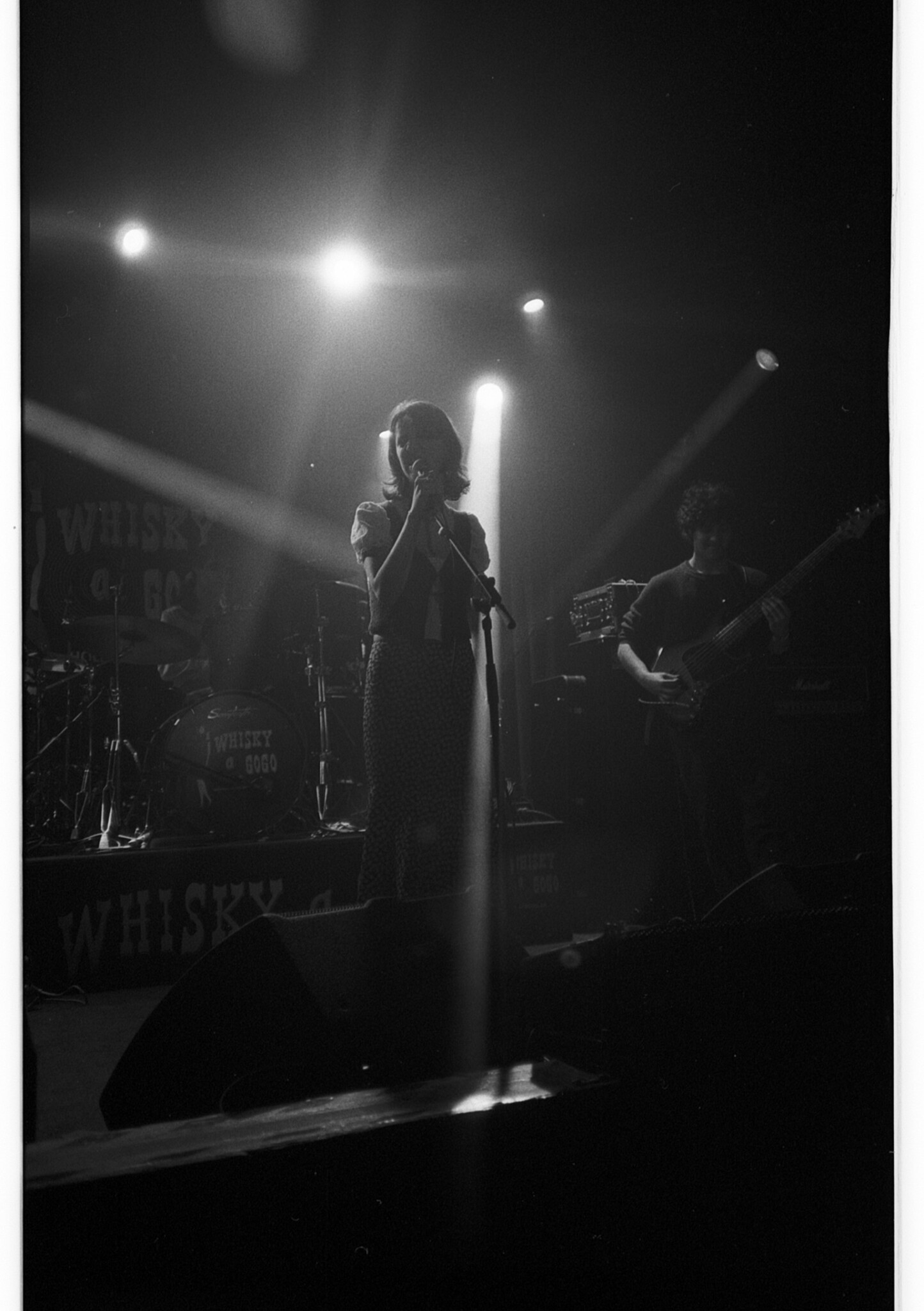

Our excitement was high but there was a problem: we couldn’t play a single song all the way through, not even close. This 8 piece band (with a damn horn section) had no clear path to get from the start of a song to the end. We all had different understandings of musical lingo, how to anticipate cues, and how to play our own instruments. Our lead guitarist, with a wonderful smile and a kind heart, was nearly eaten alive by rhythmic jargon of “and’s” and “e’s”. After many days of trying to decorate the idea of striking a chord on a certain beat in a way that was sensicle, I explained: “Imagine you’re holding a giant stack of printer paper, about a foot tall. Man that’s a thick stack. Now, when we begin this musical phrase, imagine that you hold the stack up above the ground at around the height of your shoulders, and then you drop it. The second that the imaginary stack of paper hits the ground, play this chord.” Looking back, I’m not entirely sure if that explanation got us where it needed to get us that day, but it settled in soon after, and desperate times call for desperate measures: our first ever gig was approaching. We didn’t share the musical terminology but we did share the enthusiasm, and soon after, we shared COVID. Half the band was out and quarantining, so we had to cancel our first show, heads hung low. A week or two later, without much recent practice under our belts, it was time to hop on the bus with our instruments and ride it 20 minutes east, walk a half mile with our gear, and set up at an arcade/bar as a group of eight 18 year olds with not much to show for ourselves but butterflies in our bellies and sweaty pits from all the instrument schlepping. Regardless of the moisture and nerves, once we started the set, I was in a dream state, a trance. I felt as though the version of myself that I had seen in the mirror as a 9 year old in an imaginary rock concert had come alive and manifested in reality: I was singing live for an audience with a band!! To bring myself from being a singing field dweller to being a musician on a stage felt like I had put myself in a catapult and launched myself towards embodying the role I had always wanted. The electricity I felt has not dampened even a smidge as I’ve continued to perform with different bands in different settings. It instead feels as though each performance, I get the chance to meet another part of myself to add to my musical mosaic, which has only grown in texture, color, and connections.

Ari, before we move on to more of these sorts of questions, can you take some time to bring our readers up to speed on you and what you do?

I am a firm believer in music as a form of “play.” It warms me to be joined by the existence of music as a tool to create connections, express oneself, and be vulnerable in a way that’s impossible otherwise. I have always loved the fundamental act of musicianship that is singing: anyone can do it, and in my opinion, it is the most accessible and expressive instrument to exist. There is no wrong way to sing, as long as it feels good to the singer and their health. Just like everyone else in the world with working vocal cords, I’ve always been a singer. I’ve always loved to sing and especially to sing with others. I grew up going to temple and Hebrew school and when I was in the second or third grade, I joined the senior citizen choir at my temple. I inserted myself and nobody told me not to: that’s kind of how I’ve always done it. I didn’t know anything about religion, nor did I even realize that I was singing prayers. I didn’t know what anything meant or the significance of any songs I was singing, but I knew I loved the melodies. I kept myself entertained at Hebrew School services by harmonizing to every prayer and inserting ad libs. I’d say that’s where it all began. This came in handy with my home life as well. Imagine, four stubborn people amidst a messy divorce, each of the four lacking communication skills, riddled with anger, but enamored by the joy of singing. Because I grew up right in the middle of Los Angeles, a lot of time was spent sitting in traffic, meaning that quality time included sitting in a stopping and starting vehicle where nobody had to make eye contact, but everyone was listening to the same song, singing aloud in four part harmony despite being unable to have a civil conversation. Singing is a huge part of what raised me, in this sense.

As I grew more conscious of my love of music, I swam in the sea of intentional listening, comparing timbres, instrumentation, and melodies from global musics. I dove into music from the Middle East, Bossa Nova, the British Invasion, the American Song Book, all over the Americas and my family’s favorite Broadway tunes. The intersectionality between these genres has quilted together a musical texture that represents me. In this musical quilt, I see exploration, curiosity, furthering connection to myself and others, and freedom to create whatever sounds make me feel good (a concept to use in replacement of “right or wrong”).

I feel lucky to have been entrusted by many people in my community to give singing and guitar lessons, to have a passion that surpasses a hobby but instead is the largest piece of my self-puzzle, and to have opportunities to spread out and wiggle my toes in the field of music – as an Ethnomusicology student at UW and the DJ assistant at KEXP for the world music show.

What do you think is the goal or mission that drives your creative journey?

By far, the most rewarding part about being an artist is making myself vulnerable enough to let people around me know that they can be vulnerable too. I have no interest in living life with a wall up. I’ve found that an excellent way to allow people to let their guard down is to make music and make mistakes with others. I’ve seen many friends at battle, in a staring contest with the instrument in front of them. It’s so common for people to be intimidated by musical instruments or musical settings because of the ideology that there is a good or bad way to play it. Before even striking a note, they think that they’ve done something wrong. Musicking is one of the most innate human activities, but with western ideologies that capitalize on musical ability, impossible standards are placed on anyone within ten feet of an instrument. This pressure makes the most accessible activity – making music – seem out of reach. It hurts to see this distress rob people’s freedom of expression. Fostering a musical environment towards welcoming creativity in any form – and seeing people let their guard down and create music without shame – is a sonic representation of a warmed heart. My goal is to create a safe space for music participation and make these participatory experiences more widespread, to make musicking far more accessible.

Have any books or other resources had a big impact on you?

Throughout my growing immersion in different musical communities (jazz jams at bars, performances, busking, and singing different genres through school – hindustani, jazz, choral music, opera, etc), I’ve experienced many different participatory structures. Depending on genre and region of origin, there are varying emphases on audience participation. In many genres, there is little to no separation between audience and performer: in these settings, “musicking” is accessible for everyone in the space. This ideology socializes music lovers to understand the innateness in their own music making, and avoid the pressure of participating in music only if they do it the “right” way. The sharp division between audience and performer in much of Western music perpetuates the idea that music is only for “talented” or “skilled” musicians, whereas participatory music allows everyone to offer their own expression of self.

There are a few writers who touch quite a bit on this topic, one of which is named Christopher Small, whose book, “Musicking,” explores the simplicity of what music making truly is. Music is an activity that everyone takes part in, a baby cooing, the rhythmic emphasis on some syllables over others in an everyday phrase, it’s everywhere. Unfortunately, using music as a form of earning capital through separation and elitism is common practice in the United States, with the power that money holds over the art form. Musicking should not be limited to a performance-based action for those with “skill” and “prestige” (which feeds into separation), but rather should be recognized as the collective and rhythmic sounds that humans make together through pure instinct. Through musicking comes communication, relationships, understanding of self, and interconnectedness from the syncing heartbeats with those around you. Through sitting in a chair and looking at a musician 100 feet in front of you, so much that musical expression has to offer is lost.

I developed this idea of music as an innate ability from Robert Jourdain, in his book, “Music, The Brain, and Ecstasy.” This book dives into music as simply patterns of intentional sound, rather than a prestigious concept that one must understand through music theory. This ideology blurs any lines between what makes a musician “good” or “bad,” which I think is the most important, foundational step on having the freedom to create music in a way that feeds the soul.

Contact Info:

- Instagram: ariokinmusic

- Facebook: Ari Okin

- Youtube: https://www.youtube.com/@AriOkinMusic

- Soundcloud: ariokin

Image Credits

Sasha Winett

Samuel Riera